Perceptions BOUND PERIODICAL Spring 1995 Editor Marleen Springston "7 ,".R·"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

Where Currents Connect

The Current GAHANNA PARKS & RECREATION ACTIVITY GUIDE Winter 2019-2020 Parks & Recreation WorkWhere in Gahanna? Receive the Currents Resident Discount Rate (RDR) Connect 1 Civic Leaders City of Gahanna Advisory Committees TABLE OF CONTENTS Mayor Tom Kneeland Parks & Recreation Board City Attorney Shane W. Ewald Meetings are held at 7pm on the second Civic Leaders 2 Wednesday of each month at City Hall Gahanna City Council unless otherwise noted. All meetings are Rental Facilities 3 Contact: [email protected] open to the public. Ward 1: Stephen A. Renner, Vice President Jan Ross, Chair Ward 2: Michael Schnetzer Andrew Piccolantonio, Vice Chair Aquatics 4 Ward 3: Brian Larick Cynthia Franzmann Ward 4: Jamie Leeseberg Chrissy Kaminski Active Seniors At Large: Karen J. Angelou Eric Miller 5 Nancy McGregor Daphne Moehring Brian Metzbower, President Ken Shepherd Parks Information 10 Parks & Recreation Staff Landscape Board Contact: [email protected] The Landscape Board meetings are listed online at Jeffrey Barr, Director Ohio Herb Center 11 www.gahanna.gov. Meetings are held at City Hall Stephania Bernard-Ferrell, Deputy Director unless otherwise noted. Alan Little, Parks & Facilities Superintendent All meetings are open to the public. Golf Course 12 Brian Gill, Recreation Superintendent Jane Allinder, Chair Jim Ferguson, Parks Foreman Melissa Hyde, Vice Chair Zac Guthrie, Parks & Community Services Supervisor Outdoor Experiences 13 Kevin Dengel Joe Hebdo, Golf Course Supervisor Mark DiGiando Curt Martin, Facilities Coordinator Matt Winger Camp Experiences 14 Sarah Mill, Recreation Supervisor Julie Predieri, City Forester Pam Ripley, Office Coordinator Arts & Education 15 Marty White, Facilities Foreman Recreation & Sports 16 How to register 19 Volunteer Advisory Committees The Parks & Recreation Board created the following advisory committees to assist the Department of Parks & Recreation with facilitating, planning, promoting and implementing projects with the assistance of volunteer residents. -

The Healing Forest – the Entire African American Community As a Recovery Center (M.5)

Transcript: The Healing Forest – The Entire African American Community as a Recovery Center (M.5) Presenter: Mark Sanders Recorded on June 9th, 2020 MARK SANDERS: Hello everyone. I like to start these virtual sessions with recovery stories where they give us hope. In March of 1995, I was giving a speech in Downers Grove, Illinois. That's a suburb just west of Chicago. And there was a woman sitting in the front row-- African-American woman sitting in the front row center aisle seat who asked if I was the same Mark Sanders who worked at a detox center in 1985 a decade earlier. I said, yeah, that's me. She said, I was a patient on the detox unit. You were my counselor. I don't always remember names, but I remember stories and faces. So here's her story. She was addicted to cocaine and heroin, and she supported her drug habit through prostitution. In fact, she sold her body not too far from our detox facility. And some evenings, as I was driving home, I'd see her standing on the corner. She left detox and went back to selling her body. She looked really bad to me. You know how when a person stops-- starts using drugs, they stop eating, they lose a lot of weight. So I remember looking at her some evening and saying to myself as I was driving, well, she looks really bad. I don't think she'll ever recover. Am I the only one listening to the sound of my voice who's ever worked with a client that you thought would never recover? See, that's why I'm convinced that computers will never be able to do your job. -

Jackson Preparatory School

JACKSON PREPARATORY SCHOOL NON-PROFIT U.S. POSTAGE Paid T H E Jackson, MS SENTRY Permit #93 VOL. 50, ISSUE 6 JANUARY 2020 Seniors take a walk down Wall Street subway to either the Federal After that they went to told us we would end up literal- by Jane Gray barbour Reserve or MTA Arts & Design. Maverick Capital. The group ly so exhausted by the end of the Around Town EdiTor They then ate lunch and hung went to John’s Pizza for dinner, a trip. One night we literally got out at the Capitol. After a long tradition for the Financial Man- three hours of sleep it was rough.” The Jackson Prep seniors day, they got to have fun and agement trip, before going to see On their last day in New who either have taken or are cur- eat dinner and go ice skating at Mean Girls on Broadway and York the group paid a visit to the rently enrolled in the fnancial Rockefeller Center. Afterwards, Shake Shack for desert. 9/11 Memorial and the One World management class were able to they were able to go to , and the Senior Kathryn Weir said, Observatory before they left for take a trip to New York City from top of the Rock. “Going to New York was a real- the airport. January 15th through January On Friday, they started ly fun and unique experience. I The students disem- 19th. The chaperones that ac- their day by taking the subway to don’t think I would ever have had barked in New Orleans at 8:45 companied the students on this Marymount School of New York, the possibility to go to the meet- p.m. -

Words+Images

MUSE IS THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL PUBLISHED BY THE LIT WORDS+IMAGES { FIRST ANNUAL MUSE L I T E R A R Y CO MPETITION } ISSUE02.09 VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 0 2 0 9 2contents UNREQUITED RELIGION GRANT BAILIE 6 GRANDPA RUDY ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON MARK KUHAR 7 PODIS JOHN PANZA 11 INFINITE LOSS ROB JACKSON 15 EIGHT TO FIVE, AGAINST (EXCERPT) MARY DORIA RUSSELL 18 BOXERS DON’T FLOSS AFTER EVERY BOUT JOHN DONOGHUE 20 BLUE GIRL MARK KUHAR 21 DANCING WITH SOMETHING SHIVA SAID 33rd cleveland international film festival CLAIRE MCMAHON BACKGROUND it’s starting march 19-29, 2009 tower city cinemas clevelandfilm.org LITTLE GIRL BLUE BILLY DELPS PLAYGROUND, NYC, 2003 JASON OASIS 26 A SENTIMENTAL JOURNEY AMY BRACKEN SPARKS VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 0 2 0 9 2contents UNREQUITED RELIGION GRANT BAILIE 6 GRANDPA RUDY ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON MARK KUHAR 7 PODIS JOHN PANZA 11 INFINITE LOSS ROB JACKSON 15 EIGHT TO FIVE, AGAINST (EXCERPT) MARY DORIA RUSSELL 18 BOXERS DON’T FLOSS AFTER EVERY BOUT JOHN DONOGHUE 20 BLUE GIRL MARK KUHAR 21 DANCING WITH SOMETHING SHIVA SAID 33rd cleveland international film festival CLAIRE MCMAHON BACKGROUND it’s starting march 19-29, 2009 tower city cinemas clevelandfilm.org LITTLE GIRL BLUE BILLY DELPS PLAYGROUND, NYC, 2003 JASON OASIS 26 A SENTIMENTAL JOURNEY AMY BRACKEN SPARKS Words + Images is our tag line, and for this issue, we focus on MUSE IS THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL PUBLISHED BY THE LIT Words as we publish the winners of the first annual MUSE VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 Literary Competition. -

We All Wanna Die, Too”: Emo Rap and Collective Despair in Adolescent America

“WE ALL WANNA DIE, TOO”: EMO RAP AND COLLECTIVE DESPAIR IN ADOLESCENT AMERICA A thesis submitted to the Kent State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors by Nina Palattella May 2020 Thesis written by Nina Palattella Approved by ________________________________________________________________, Advisor ______________________________________________, Chair, Department of English Accepted by ___________________________________________________, Dean, Honors College ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………....v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS……………………………………………………….………vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….…1 II. “I WANT EVERYONE TO KNOW THAT I DON’T CARE”: CASE STUDY OF LIL PEEP……………………………………….….16 III. “BETTER OFF DYING”: DOES EMO RAP ASSUAGE OR AMPLIFY MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS?…………………………………… 26 IV. “XANS DON’T MAKE YOU”: EMO RAP’S GLORIFICATION OF, AND RECKONING WITH, DRUG ABUSE……………………………43 V. “WE ALL WANNA DIE, TOO”: HOW IS EMO RAP BRANDED, AND WHAT KIND OF LEGACY ARE ITS STARS LEAVING? ...………….60 VI. “WHEN I DIE YOU’LL LOVE ME”: WHAT DOES EMO RAP MEAN, AND WHAT DIRECTIONS MIGHT IT TAKE IN THE FUTURE? ….80 WORKS CITED …………………………………………………………………………89 iv LIST OF FIGURES Fig. 1. Lil Peep (Gustav Åhr) …………………………………………………17 Fig. 2. Still from “Awful Things” Music Video ………………………………21 Fig. 3. XXXTentacion (Jahseh Onfroy) ……………………………………….29 Fig. 4. Lil Xan (Diego Leanos) ……...………………………………………...36 Fig. 5. nothing,nowhere. (Joe Mulherin) ……………………………………...50 Fig. 6. Still from “Lean Wit Me” Music Video ……………………………….52 Fig. 7. Lil Uzi Vert (Symere Woods) ………………………………………….76 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to offer my sincere thanks to everyone who made this thesis possible and who supported me as I completed it. I am especially grateful to Dr. Ryan Hediger for advising this project and encouraging me throughout the long process. -

Freshwater Mollusks of the Middle Mississippi River

Freshwater mollusks of the middle Mississippi River Jeremy Tiemann Illinois Natural History Survey Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1816 South Oak Street Champaign, IL 61820 217-244-4594 [email protected] Prepared for Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Preservation Fund Grant Agreement Number 13-031W Project duration: 31 July 2012 – 31 December 2013 Illinois Natural History Survey Technical Report 2014 (03) 20 January 2014 Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign William Shilts, Executive Director Illinois Natural History Survey Brian D. Anderson, Director 1816 South Oak Street Champaign, IL 61820 217-333-6830 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 - Freshwater mollusks of the middle Mississippi River Abstract ....................................................................................................................2 Introduction ..............................................................................................................2 Methods....................................................................................................................3 Results ......................................................................................................................3 Discussion ................................................................................................................4 Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................6 Literature cited .........................................................................................................6 -

Chapter 3 Ecosystem Management

CHAPTER 3: ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT Notable projects from the 2015-2016 reporting year are discussed in the Project Highlights section of this chapter. This reporting year covers twelve months, from July 1, 2015 through June 30, 2016. Last year’s report covered only nine months, from October 1, 2014 through June 30, 2015. Threat control efforts are summarized for each Management Unit (MU) or non-MU land division. Weed control and restoration data is presented with minimal discussion. For full explanations of project prioritization and field techniques, please refer to the 2007 Status Report for the Makua and Oahu Implementation Plans (MIP and OIP; http://manoa.hawaii.edu/hpicesu/DPW/2007_YER/default.htm). Ecosystem Restoration Management Unit Plans (ERMUP) have been written for many MUs and are available online at http://manoa.hawaii.edu/hpicesu/dpw_ermp.htm. Each ERMUP details all relevant threat control and restoration actions in each MU for the five years immediately following its finalization. The ERMUPs are working documents; OANRP modifies them as needed and can provide the most current versions on request. This year, the Kaala and Ohikilolo (Lower and Upper) ERMUPs were revised, and the Kamaili ERMUP was completed; they are included as Appendices 3-1 to 3-4. 3.1 WEED CONTROL PROGRAM SUMMARY MIP/OIP Goals The stated MIP/OIP goals for weed control are: Within 2m of rare taxa: 0% alien vegetation cover Within 50m of rare taxa: 25% or less alien vegetation cover Throughout the remainder of the MU: 50% or less alien vegetation cover Given the wide variety of habitat types, vegetation types, and weed levels encompassed in the MUs, these IP objectives should be treated as guidelines and adapted to each MU as management begins. -

North Hampton Events

NORTH HAMPTON EVENTS NEW HAMPSHIRE, NATIONAL (in-progress) & WORLD EVENTS (does not include all births/deaths,..) (selected/in-progress) Selectmen: Samuel Fogg, David M. 1861 Abraham Lincoln 16th President of U.S. Dow, Albert D. Brown. 5 6’4” tall. First president to wear a beard. First Lady: Mary Todd Lincoln. Levi Brown, Elva Dearborn die. 37 Buchanan said to Lincoln, “If you are as happy, my dear sir, on entering this Charles E. Seavey builds a blacksmith house as I am to leave it and returning shop with ox-sling on Hobbs Road home, you are the happiest man in the across from Deacon Leavitt’s House. country.” 17,158 5,10 Charles E. Marston and Orace Fogg The Apache declare war on the United served at the First Battle of Bull Run, States. 31 also known as the First Battle of Manassas (the name used by Kansas is 34th state in the union. 158 Confederate forces and still often used in the Southern United States), was The transcontinental telegraph is fought July 21, 1861, near Manassas, completed. 31 Virginia. It was the first major land battle of the American Civil War. 200 The Confederate States of America is formed. Civil War begins. Over the 10/25 Charles E. Marston (17-1/2 years course of the war, 45,616 New old) dies from wound received after 7 Hampshire men enlist for the Union, 0 days on the battle field of Bull Run. 37 for the Confederates. 31, 195 William J. Breed joins the Grand Army of the Republic.14 Over the course of the war, North Hampton volunteers number to 62 with 6 more in the Navy. -

Scenes for Teens

Actor’s choice: scenes for teens edited by JAson PizzArello Copyright © 2010 Playscripts, Inc. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying of this book or excerpts from this book is strictly forbidden by law. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, by any means now known or yet to be invented, including photocopying or scanning, without prior permission from the publisher. Actor’s Choice: Scenes for Teens is published by Playscripts, Inc., 450 Seventh Avenue, Suite 809, New York, New York, 10123, www.playscripts.com Cover design by Michael Minichiello Text design and layout by Kimberly Lew First Edition: September 2010 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CAUTION: These scenes are intended for audition and classroom use; permission is not required for those purposes only. The plays represented in this book (the “Plays”) are fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations, whether through bilateral or multilateral treaties or otherwise, and including, but not limited to, all countries covered by the Berne Convention, the Pan-American Copyright Convention and the Universal Copyright Convention. All rights, including, without limitation, professional and amateur stage rights; motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording rights; rights to all other forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction not known or yet to be invented, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, DVD, information storage and retrieval systems and photocopying; and the rights of translation into non-English languages, are strictly reserved. -

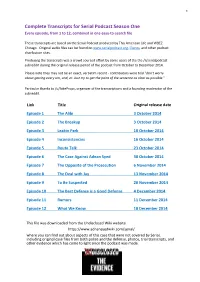

Serial Podcast Season One Every Episode, from 1 to 12, Combined in One Easy-To-Search File

1 Complete Transcripts for Serial Podcast Season One Every episode, from 1 to 12, combined in one easy-to-search file These transcripts are based on the Serial Podcast produced by This American Life and WBEZ Chicago. Original audio files can be found on www.serialpodcast.org, iTunes, and other podcast distribution sites. Producing the transcripts was a crowd sourced effort by some users of the the /r/serialpodcast subreddit during the original release period of the podcast from October to December 2014. Please note they may not be an exact, verbatim record - contributors were told "don't worry about getting every um, and, er. Just try to get the point of the sentence as clear as possible." Particular thanks to /u/JakeProps, organizer of the transcriptions and a founding moderator of the subreddit. Link Title Original release date Episode 1 The Alibi 3 October 2014 Episode 2 The Breakup 3 October 2014 Episode 3 Leakin Park 10 October 2014 Episode 4 Inconsistencies 16 October 2014 Episode 5 Route Talk 23 October 2014 Episode 6 The Case Against Adnan Syed 30 October 2014 Episode 7 The Opposite of the Prosecution 6 November 2014 Episode 8 The Deal with Jay 13 November 2014 Episode 9 To Be Suspected 20 November 2014 Episode 10 The Best Defense is a Good Defense 4 December 2014 Episode 11 Rumors 11 December 2014 Episode 12 What We Know 18 December 2014 This file was downloaded from the Undisclosed Wiki website https://www.adnansyedwiki.com/serial/ where you can find out about aspects of this case that were not covered by Serial, including original case files from both police and the defense, photos, trial transcripts, and other evidence which has come to light since the podcast was made. -

Aspects of Near-Death Experiences That Bring About Life Change

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ASPECTS OF NEAR-DEATH EXPERIENCES THAT BRING ABOUT LIFE CHANGE A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand KATE STEADMAN 2015 1 Abstract The literature on near-death experiences (NDEs) and its aftereffects is steadily growing. Common elements of a NDE have been widely documented, as well as a large body of common aftereffects. These aftereffects leave long lasting and dramatic impressions on the experiencers, yet no relationship between the content and features of a NDE and its aftereffects has been identified. The current study aims to investigate the relationship between NDE-related factors and their aftereffects in an Aotearoa New Zealand sample. Both quantitative and qualitative methods were used to obtain data in order to thoroughly investigate how NDEs manifest, how they are interpreted, and how they affect the people of Aotearoa New Zealand. Results showed that several situational factors and depth of participants NDEs were able to predict the degree of life changes they experienced as a result. Some evidence was provided to suggest that the type of NDE experienced also affected participants life changes. The current studies sample consisted of mostly New Zealand European/ Pākehā which limited ethnic interpretation of the findings. It is recommended that future studies include a culturally diverse sample of people from Aotearoa New Zealand to complement the culturally diverse nation.