What Ideas Do Viewers Have About

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I Eventss I FOOD on Staffordshirewhatson.Co.Uk

Staffordshire Cover Online.qxp_Staffordshire Cover 24/11/2016 10:29 Page 1 Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands ISSUE 372 DECEMBER 2016 SCOTT CAPURRO Staffordshire AT LICHFIELD GARRICK ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On staffordshirewhatson.co.uk inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide p02 (IFC) Staffs.qxp_Layout 1 21/11/2016 16:08 Page 1 Contents December Staffs.qxp_Layout 1 21/11/2016 14:22 Page 2 December 2016 Contents Shrewsbury Winter Festival - festive fun in the town’s Quarry Park page 47 Placebo Josh Widdicombe Marvel Universe the list Alternative rock band celebrate Devon funnyman plays the Superheroes assemble for live Your 16-page 20th anniversary Wolverhampton Civic... Midlands show week-by-week listings guide page 14 page 20 page 45 page 53 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 14. Music 20. Comedy 24. Theatre 39. Film 42. Visual Arts 45. Events @whatsonwolves @whatsonstaffs @whatsonshrops Wolverhampton What’s On Magazine Staffordshire What’s On Magazine Shropshire What’s On Magazine Managing Director: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 Whats On Matt Rothwell [email protected] 01743 281719 Editorial: Lauren Foster [email protected] 01743 281707 MAGAZINE GROUP Sue Jones [email protected] 01743 281705 Brian O’Faolain [email protected] 01743 281701 Abi Whitehouse [email protected] 01743 281716 Ryan Humphreys [email protected] 01743 281722 Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Rhian Atherton [email protected] 01743 281726 Contributors: Graham Bostock, James Cameron-Wilson, Heather Kincaid, David Vincent, Katherine Ewing, Lauren Cox Publisher and CEO: Martin Monahan Accounts Administrator: Julia Perry [email protected] 01743 281717 This publication is printed on paper from a sustainable source and is produced without the use of elemental chlorine. -

Official List of Houston County Qualified Voters State of Alabama Houston County

OFFICIAL LIST OF HOUSTON COUNTY QUALIFIED VOTERS STATE OF ALABAMA HOUSTON COUNTY As directed by the Code of Alabama, I, PATRICK H. DAVENPORT, Judge of Probate, hereby certify that the within constitutes a full and correct list of all qualified electors, as the same appears from the returns of the Board of Registrars, on file in this office, and who will be entitled to vote in any election held in said county. Notice is hereby given to any voter duly registered whose name has been inadvertently, or through mistake, omitted from the list of qualified voters herein published, and who is legally entitled to vote, shall have ten days from the date of thispublication to have his or her name entered upon the list of qualified voters, upon producing proof to the Board of Registrars of said County that his or her name should be added to said list. This list does not include names of persons who registered after Jan 16, 2020. A supplement list will be published on or before Feb 25, 2020. PATRICK H. DAVENPORT Judge of Probate ANDREW BELLE ANNETTE BURKS DELISA THOMAS CUNNINGHAM KYLE JACOB EDWARDS MICHAEL WAYNE GOODWIN SHARRON ANNELLE COMM CENTER BLACK MORRIS K BURNEY HANSEL CURETON JAMES T EDWARDS MICHELLE MAIRE GOOLSBY KIMBERLY SHANEDRA ABBOTT CLARISSE ANN BLACK NATASHA LYNETTE BURNSED ROBERT AUSTIN III CURLIN STACY DENISE EIKER REBECCA GORDON MAE EVELYN ABBOTT EARL LEIGHTON III BLACK SARAH FRANCIS BURROUGHS APRIL ANTRONN CURRY ANTHONY DWAYNE ELLARD GRANADA IRENE GORLAND KIMBERLY DARLINE ADAMS CHANEY ALEDIA BLACKBURN MICHAEL EDWARD BURROUGHS KHAALIS -

Caroline Cornish Management

CAROLINE CORNISH MANAGEMENT 12 SHINFIELD STREET, LONDON W12 OHN Tel: 44 (0) 20 8743 7337 Mobile: 07725 555711 e-mail: [email protected] www.carolinecornish.co.uk MAGI VAUGHAN - HAIR & MAKE-UP DESIGNER BAFTA AWARD WINNER - 3 BAFTA NOMINATIONS 1 EMMY AWARD - 1 EMMY NOMINATION 2 MAKE-UP ARTISTS & HAIR STYLISTS GUILD AWARDS Make-Up application by AIR-BRUSH Special Make-Up Effects/Prosthetics Application and Making of Gelatine & Silicone Pieces Character and Period Makeup/Hair Work including Wigs and Hairpieces Countries Worked In: Croatia, Czech Republic, France, Holland, Hungary, Malta, Mallorca, Morocco, Romania, South Africa Languages Spoken: Fluent Welsh, Basic French and Spanish, Hungarian and Italian AVENUE 5 Prod Co: Jettison Productions/HBO Producers: Kevin Loader, Richard Daldry Directors: Armando Iannuci + TBC ALEX RIDER II Prod Co: Eleventh Hour Productions/Sony Producer: Richard Burrell Directors: TBC THE MALLORA FILES II Production Suspended due to Coronavirus 10x45min Drama Series Producer: Dominic Barlow Directors: Bryn Higgins, Rob Evans, Craig Pickles, Christina Ebohon-Green SUPPRESSION Prod Co: Snowdonia Feature Film Producers: Andrew Baird, Tom Warren Director: J Mackye Gruber CASTLE ROCK II Prod Co: Scope Productions Moroccan Unit Producer: Debbie Hayn-Cass. Director: Phil Abraham Drama Series Ep 202/204 THE MALLORCA FILES Prod Co: Cosmopolitan Pictures/Clerkenwell Films/BBC 10 x 45 min Drama Series Producer: Dominic Barlow Mallorca Director(s): Bryn Higgins, Charlie Palmer, Rob Evans, Gordon Anderson Featuring: Elen Rhys, Julian Looman RIVIERA II Prod Co: Archery Pictures/SKY 10pt Drama Series Producer: Sue Howells South of France Directors: Hans Herbots, Paul Walker, Destiny Ekaragha Featuring: Poppy Delevingne, Roxanne Duran, Jack Fox, Dimitri Leonidas, Lena Olin, Juliet Stephenson, Julia Stiles Registered Office: White Hart House, Silwood Road, Ascot SL5 0PY. -

STEPHEN MOYER in for ITV, UK

Issue #7 April 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming LIVING WITH SECRETS STEPHEN MOYER IN for ITV, UK MIPTV Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com Scripted OFC Apr17.indd 2 13/03/2017 16:39 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. Brand new second season. based on the acclaimed dilemmas, this five-part series Winner – TVFI Prix Export Fiction Award 2017. author Åsa Larsson’s tells the amazing true story of CANAL+ CREATION ORIGINALE best-selling crime novels. a notorious criminal barrister. Sinister events engulf a group of friends Ellen follows a difficult teenage girl trying A husband searches for the truth when A country pub singer has a chance meeting when they visit the abandoned Black to take control of her life in a world that his wife is the victim of a head-on with a wealthy city hotelier which triggers Lake ski resort, the scene of a horrific would rather ignore her. Winner – Best car collision. Was it an accident or a series of events that will change her life crime. Single Drama Broadcast Awards 2017. something far more sinister? forever. New second series in production. MIPTV Stand C20.A banijayrights.com Banijay_TBI_DRAMA_DPS_AW.inddScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay Apr17.indd 2 1 15/03/2017 12:57 15/03/2017 12:07 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. -

Page-1-16 Feb11.Indd

G Before your next trip to Britain check out the BBIGI S ING Discounts on: AV • BritRail Passes • The London Eye SSAVINGS• The London Pass • Tower of London • The Original London Sightseeing Bus Tour Go to: ujnews.com [click on the VisitBritain Shop logo] Vol. 28 No. 11 February 2011 WEYBRIDGE in Surrey Government Plans Major was last month named as Britain’s most fertile town according to a study by MMostost FFertileertile Health Care Reform Gurgle.com. Women living there PRIME MINISTER David Cam- NHS. I think we do need to make more take an average of just TTownown IInn BBritainritain eron said last month that his gov- fundamental changes.” three months to con- ernment will make fundamental PUBLISH ceive, compared to the changes to Britain’s state-run The government was about to publish UK average of six months, its Health and Social Care Bill. NNamedamed health care system, but critics Some doctors welcome the changes, but and are more likely to warned the reforms could under- critics claim the scale of the reforms could fall pregnant than in any mine one of the country’s most vital other area reported the cause chaos. website. institutions. In a letter published in The Times The town is part of the The Conservative leader said he would newspaper groups, including doctors’ posh Elmbridge district, save money and cut red tape by giving body the British Medical Association, the named last month as control over management to family prac- Royal College of Nursing and trade unions Britain’s best place to titioners rather than bureaucrats, and allow warned that the scale and pace of reform live, with official statistics private companies to bid for contracts made the changes “extremely risky and showing its birth rate shot within the National Health Service. -

25 Years of Eastenders – but Who Is the Best Loved Character? Submitted By: 10 Yetis PR and Marketing Wednesday, 17 February 2010

25 years of Eastenders – but who is the best loved character? Submitted by: 10 Yetis PR and Marketing Wednesday, 17 February 2010 More than 2,300 members of the public were asked to vote for the Eastenders character they’d most like to share a takeaway with – with Alfie Moon, played by actor Shane Ritchie, topping the list of most loved characters. Janine Butcher is the most hated character from the last 25 years, with three quarters of the public admitting they disliked her. Friday marks the 25th anniversary of popular British soap Eastenders, with a half hour live special episode. To commemorate the occasion, the UK’s leading takeaway website www.Just-Eat.co.uk (http://www.just-eat.co.uk) asked 2,310 members of the public to list the character they’d most like to ‘have a takeaway with’, in the style of the age old ‘who would you invite to a dinner party’ question. When asked the multi-answer question, “Which Eastenders characters from the last 25 years would you most like to share a takeaway meal with?’, Shane Richie’s Alfie Moon, who first appeared in 2002 topped the poll with 42% of votes. The study was entirely hypothetical, and as such included characters which may no longer be alive. Wellard, primarily owned by Robbie Jackson and Gus Smith was introduced to the show in 1994, and ranked as the 5th most popular character to share a takeaway with. 1.Alfie Moon – 42% 2.Kat Slater – 36% 3.Nigel Bates – 34% 4.Grant Mitchell – 33% 5.Wellard the Dog – 30% 6.Peggy Mitchell – 29% 7.Arthur Fowler – 26% 8.Dot Cotton – 25% 9.Ethyl Skinner – 22% 10.Pat Butcher – 20% The poll also asked respondents to list the characters they loved to hate, with Janine Butcher, who has been portrayed by Rebecca Michael, Alexia Demetriou and most recently Charlie Brooks topping the list of the soaps most hated, with nearly three quarters of the public saying listing her as their least favourite character. -

Dirk Nel Director of Photography

Dirk Nel Director of Photography Credits include: GRACE Director: Henrik Georgsson Mystery Crime Drama Producer: Kiaran Murray-Smith Featuring: John Simm, Richie Campbell, Rakie Ayola Production Co: Second Act Productions / ITV REDEMPTION Director: John Hayes Mystery Crime Drama Series Producer: John Wallace Featuring: Paula Malcomson, Abby Fitz, Thaddea Graham Production Co: Tall Story Pictures / Metropolitan Films Virgin Media One / ITV WHITSTABLE PEARL Director: David Caffrey Darkly Comic Crime Drama Series Producer: Guy Hescott Featuring: Kerry Godliman, Howard Charles, Frances Barber Production Co: Buccaneer Media / Acorn TV LIFE Directors: Iain Forsyth, Kate Hewitt, Jane Pollard Drama Producer: Kate Crowther Featuring: Alison Steadman, Adrian Lester, Victoria Hamilton Production Co: Drama Republic / BBC One MARCELLA Director: Ashley Pearce Crime Noir Thriller Producer: Elliott Swift Featuring: Anna Friel, Aaron McCusker, Hugo Speer Production Co: Buccaneer Media / Netflix / ITV ACKLEY BRIDGE Director: Rachna Suri Drama Producer: Jo Johnson Featuring: Jo Joyner, Liz White, Paul Nicholls Production Co: The Forge / Channel 4 VERA: COLD RIVER Director: Carolina Giammetta Crime Drama Producer: Will Nicholson Featuring: Brenda Blethyn, Paul Kaye, Kenny Doughty Production Co: ITV BLACK EARTH RISING Director: Hugo Blick Thriller Drama Series Producer: Abi Bach Eps 1, 6, 8 Featuring: John Goodman, Michaela Coel, Harriet Walter Production Co: Drama Republic / BBC Two Dirk Nel | Director of Photography 2 MAIGRET IN MONTMARTRE Director: Thaddeus -

PDF (Thesis Document)

The impact of physical and mental reinstatement of context on the identifiability of facial composites by Cristina Fodarella A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire July 2020 !i ! STUDENT DECLARATION FORM Concurrent registration for two or more academic awards *I declare that while registered for the research degree, I was with the University’s specific permission, a registered candidate for the following award: ‘Associate Fellow of The Higher Education Academy’ Material submitted for another award *I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work Collaboration Where a candidate’s research programme is part of a collaborative project, the thesis must indicate in addition clearly the candidate’s individual contribution and the extent of the collaboration. Please state below: *Not applicable Signature of Candidate Type of Award Doctor of Philosophy School Psychology !ii Abstract Numerous studies demonstrate that memory recall is improved by reflecting upon, or revisiting, the environment in which information to-be-recalled was encoded. The current thesis sought to apply these ‘context reinstatement’ (CR) techniques in an attempt to improve the effectiveness of facial composites—likenesses of perpetrators constructed by witnesses and victims of crime. Participant- constructors were shown an unfamiliar target face in an unfamiliar environment (e.g., an unknown café). The following day, participants either revisited the environment (physical context reinstatement) or recalled the environmental context in detail along with their psychological state at the time (mental context reinstatement, Detailed CR); they then freely recalled the face and constructed a facial composite using a holistic (EvoFIT) or a feature system (PRO-fit). -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'. -

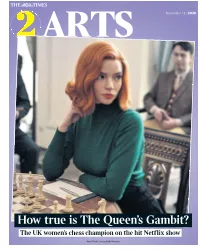

How True Is the Queen's Gambit?

ARTS November 13 | 2020 How true is The Queen’s Gambit? The UK women’s chess champion on the hit Netflix show Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon 2 1GT Friday November 13 2020 | the times times2 Caitlin 6 4 DOWN UP Moran Demi Lovato Quote of It’s hard being a former Disney child the Weekk star. Eventually you have to grow Celebrity Watch up, despite the whole world loving And in New!! and remembering you as a cute magazine child, and the route to adulthood the Love for many former child stars is Island star paved with peril. All too often the Priscilla way that young female stars show Anyabu they are “all grown up” is by Going revealed her Sexy: a couple of fruity pop videos; preferred breakfast, 10 a photoshoot in PVC or lingerie. which possibly 8 “I have lost the power of qualifies as “the most adorableness, but I have gained the unpleasant breakfast yet invented DOWN UP power of hotness!” is the message. by humankind”. Mary Dougie from Unfortunately, the next stage in “Breakfast is usually a bagel with this trajectory is usually “gaining cheese spread, then an egg with grated Wollstonecraft McFly the power of being in your cheese on top served with ketchup,” This week the long- There are those who say that men mid-thirties and putting on 2st”, she said, madly admitting with that awaited statue of can’t be feminists and that they cannot a power that sadly still goes “usually” that this is something that Mary Wollstonecraft help with the Struggle. -

Report Title Here Month Here

Alcohol & Soaps Drinkaware Media Analysis September 2010 © 2010 Kantar Media 1 CONTENTS •Introduction 3 •Executive Summary 5 •Topline results 7 •Coronation Street 16 •Eastenders 23 •Emmerdale 30 •Hollyoaks 37 •Appendix 44 Please use hyperlinks to quickly navigate this document. © 2010 Kantar Media 2 INTRODUCTION •Kantar Media Precis was commissioned to conduct research to analyse the portrayal of alcohol and tea in the four top British soap operas aired on non-satellite television, Coronation Street, Eastenders, Emmerdale and Hollyoaks. The research objectives were as follows: •To explore the frequency of alcohol use on British soaps aired on non-satellite UK television •To investigate the positive and negative portrayal of alcohol •To explore the percentage of interactions that involve alcohol •To explore the percentage of each episode that involves alcohol •To assess how many characters drink over daily guidelines •To explore the relationship between alcohol and the characters who regularly/excessively consume alcohol •To look further into the link between the location of alcohol consumption and the consequences depicted •To identify and analyse the repercussions, if any, of excessive alcohol consumption shown •To explore the frequency of tea use on British soaps aired on non-satellite UK television •Six weeks of footage was collected for each programme from 26th July to 6th September 2010 and analysed for verbal and visual instances of alcohol and tea. •In total 21.5 hours was collected and analysed for Emmerdale, 15.5 hours for Coronation Street, 15.5 hours for Hollyoaks and 13 hours for Eastenders. © 2010 Kantar Media 3 INTRODUCTION cont. •A coding sheet was formulated in conjunction with Drinkaware before the footage was analysed which enabled us to track different types of beverages and their size (e.g. -

Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17

Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport by command of Her Majesty © BBC Copyright 2017 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Photographs are used ©BBC or used under the terms of the PACT agreement except where otherwise identified. Permission from copyright holders must be sought before any photographs are reproduced. You can download this publication from bbc.co.uk/annualreport BBC Pay Disclosures July 2017 Report from the BBC Remuneration Committee of people paid more than £150,000 of licence fee revenue in the financial year 2016/17 1 Senior Executives Since 2009, we have disclosed salaries, expenses, gifts and hospitality for all senior managers in the BBC, who have a full time equivalent salary of £150,000 or more or who sit on a major divisional board. Under the terms of our new Charter, we are now required to publish an annual report for each financial year from the Remuneration Committee with the names of all senior executives of the BBC paid more than £150,000 from licence fee revenue in a financial year. These are set out in this document in bands of £50,000.