Symposium 2 May.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honour of Distinction 2003, Soc. Protect. Env. & Sust Dev

BIODATA OF PROFESSOR J. S. SINGH 1. Full Name: JAMUNA SHARAN SINGH 2. Designation: Professor Emeritus 3. Date of Birth: December 26, 1941 4. Present Address: Department of Botany, Banaras Hindu University Varanasi 221005, INDIA, and Botanical Survey of India, Allahabad 211002 Fax: 0542-2368174; Tel. 0542-2368399 (Off.); 2369093 (Res.) ; 09335178355 (Mobile) E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 5. Academic Qualification: B.Sc., University of Allahabad, 1957. M.Sc., University of Allahabad, 1959. Ph.D., Banaras Hindu University, 1967. 6. Academic Distinction: Topped Allahabad University twice: (a) in B.Sc. in Zoology and was awarded Dr. Ram Saran Dass Memorial Silver Medal for the same (1957); (b) in M.Sc. in Botany (1959). 7. Awards: Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar prize for the year 1980 for research in Biological Sciences, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India. Pitamber Pant National Environment Fellowship, 1984, Ministry of Environment and Forests, Govt. of India. Swami Pranavanand Saraswati Award for the year 1985 for research in Environment and Ecology, University Grants Commission, India. Dr. Birbal Sahni Gold Medal (1999), Indian Botanical Society Prof. S.B. Saksena Memorial Medal (1999), Indian National Science Academy Biodiversity Lecture Award (2009), National Academy of Sciences B N Chopra Lecture Award (2010), Indian National Science Academy Honour of Distinction 2003, Soc. Protect. Env. & Sust Dev. Vidwadbhushan 2005, Akhil Bhartiya Vidwat Parishad Life time Achievement Award 2005, AWA 9. Fellowship and Membership of Science Academies/Societies: Fellow, Third World Academy of Sciences Fellow, Indian National Science Academy Fellow, Indian Academy of Sciences Fellow, National Academy of Sciences, India Fellow, International Society for Tropical Ecology Fellow, National Institute of Ecology, India Fellow, Indian Range Management Society Fellow, Central Himalayan Environment Association. -

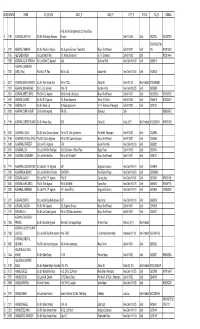

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

Pronouncement List File:///C:/Users/Admin/Desktop/Html/2020 01 07 B M.Htm

Pronouncement List file:///C:/Users/Admin/Desktop/html/2020_01_07_b_m.htm URGENT D.B. I MOTION PETITION FOR THE TUESDAY DATED 07/01/2020 CR NO 1 HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE ARUN PALLI 101 CM-4133-LPA-2019 (SCOSBHR) UTTAR HARYANA BIJLI VITRAN NIGAM LTD AND OTHERS V/S SUNDER DEEPINDER SINGH NALWA (DELAY(F)) SINGH RAWAT AND OTHERS CM-4132-LPA-2019 DEEPINDER SINGH NALWA CM-4134-LPA-2019 DEEPINDER SINGH NALWA & O&M LPA-1838-2019 DEEPINDER SINGH NALWA (LPA 1639/19 FOR 05.05.2020) 102 CM-19689-CWP-2019 (HUIDUTUOI) GURJEET SINGH AND ORS V/S UNION OF INDIA AND ORS RAJVINDER SINGH BAINS SATYA PAL JAIN (SR. ADV.), AG PB (POR) WITH CM-19690-CWP-2019 GURJEET SINGH AND ORS V/S UNION OF INDIA AND ORS RAJVINDER SINGH BAINS RAJVINDER SINGH BAINS , A.G. PUNJAB , GURINDER SINGH ATTARIWALA , IN CWP-32611-2019 MOHAN SINGH CHAUHAN , VIVEK SINGLA 103 CWP-37058-2019 (GREEN) RAJ KUMARI POULTRY FARM V/S STATE OF HARYANA AND OTHERS Manoj Kumar Taya ADVOCATE GENERAL HARYANA (OTHER) 104 CWP-37690-2019 SKYADS DIGITAL LLP V/S STATE OF HARYANA AND OTHERS AASHISH CHOPRA A.G. HARYANA (OTHER) 105 LPA-490-2019 (G/M) JAMUNA DEVI ALIAS JYOTI AND OTHERS V/S STATE OF HARYANA AND RAMAN GAUR G.S. DHALIWAL, A.G. HARYANA, MANIK AHLUWALIA (CWP-15687-2018) OTHERS 106 LPA-1282-2019 (SERPB) BALWANT SINGH V/S STATE OF PUNJAB AND OTHERS JASMINDER PAL SINGH SANDHU A.G. PUNJAB (CWP-18851-2012) WITH LPA-1994-2016 MEHAL SINGH V/S STATE OF PUNJAB AND ANR PARVEEN KUMAR GARG CM-4121-LPA-2016 PARVEEN KUMAR GARG CM-4122-LPA-2016 PARVEEN KUMAR GARG WITH LPA-1455-2019 RAJ PAL SINGH -

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

U.P. POWER CORPORATION LTD. CONTRIBUTORY PROVIDENT FUND TRUST 14-Ashok Marg, Shakti Bhawan Vistar, Lucknow-226001 Number Allotment System

U.P. POWER CORPORATION LTD. CONTRIBUTORY PROVIDENT FUND TRUST 14-Ashok Marg, Shakti Bhawan Vistar, Lucknow-226001 Number Allotment System Report Period From 01/04/2018 to 27/09/2018 Allotted CPF List Sl.No. CPF NO. Name Designation Father's Name Unit Name 1 UPPCL/CPF/21047 PREM CHAND JE GOPI CHAND ELECT DISTRIBUTION DIVISION-I , GHAZIPUR 2 UPPCL/CPF/21048 MAHESH KUMAR T.G-II RAMRAJ ELECT DISTRIBUTION DIV-II , ALLAHABAD 3 UPPCL/CPF/21049 KHWAZUDDIN JE SHEKH KALLU ELECTRICITY DISTR KAHAN DIVISION , BANDA 4 UPPCL/CPF/21050 MANISH KUMAR T.G-II LATE-RAM ELE DISTRIBUTION LOCHAN DIVISION-I , FAIZABAD 5 UPPCL/CPF/21051 MOHIT PEON LATE-BARSATI ELECT URBAN DISTR DIVISION RAJBHAWAN , LUCKNOW 6 UPPCL/CPF/21052 ANSHU GAUTAM PEON LATE-BHAGWAND ELECT URBAN DISTR EEN DIVISION RAJBHAWAN , LUCKNOW 7 UPPCL/CPF/21053 ASHVINEE KUMAR JE SHATRUGHNA ELECT DIST DIVISION-II , LAKHIMPUR 8 UPPCL/CPF/21055 IRFAN AHMED JE AHMED ELECT 765 KV S\S DIVISION , UNNAO 9 UPPCL/CPF/21054 MAHANAND KUMAR JE NITYANAND ELECT 765 KV S\S DIVISION VERMA KUMAR VERMA , UNNAO 10 UPPCL/CPF/21056 MANISH KUMAR AA RAMESH CHAND ELECT 400 KV S\S DIVISION , AGRA 11 UPPCL/CPF/21057 HARSHIT VIKAS SHRAMIK NIRANJAN SINGH ELECT 400 KV S\S DIVISION , AGRA 12 UPPCL/CPF/21058 ROHIT KUMAR SHRAMIK CHANDRA PAL ELECT DISTR DIVISION , SINGH KASGUNJ 13 UPPCL/CPF/21059 RIYAZ ALI SHRAMIK LATE-INDAZ ALI KESCO, , KANPUR 14 UPPCL/CPF/21060 PANKAJ SHRAMIK LATE-BHAGWAND ELECT URBAN DISTR EEN DIVISION AISHBAGH , LUCKNOW 15 UPPCL/CPF/21061 TARUN KUMAR OA-III LATE-NAVBHAR ELE DISTR DIV DHAMPUR , SINGH BIJNOR 16 UPPCL/CPF/21062 SANDEEP RAJ T.G-II LT. -

Zone Wise List of NASI Fellows

The National Academy of Sciences, India (The Oldest Science Academy of India) Zone wise list of Fellows & Honorary Fellows (2021) 5, Lajpatrai Road, Prayagraj – 211002, UP, India 1 The list has been divided into six zones; and each zone is further having the list of scientists of Physical Sciences and Biological Sciences, separately. 2 The National Academy of Sciences, India 5, Lajpatrai Road, Prayagraj – 211002, UP, India Zone wise list of Fellows Zone 1 (Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, West Bengal, Meghalaya, Assam, Mizoram, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, Manipur and Sikkim) (Section A – Physical Sciences) ACHARYA, Damodar, Chairman, Advisory Board, SOA Deemed to be University, Khandagiri Squre, Bhubanesware - 751030; ACHARYYA, Subhrangsu Kanta, Emeritus Scientist (CSIR), 15, Dr. Sarat Banerjee Road, Kolkata - 700029; ADHIKARI, Satrajit, Sr. Professor of Theoretical Chemistry, School of Chemical Sciences, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, 2A & 2B Raja SC Mullick Road, Jadavpur, Kolkata - 700032; ADHIKARI, Sukumar Das, Formerly Professor I, HRI,Ald; Professor & Head, Department of Mathematics, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda University, Belur Math, Dist Howrah - 711202; BAISNAB, Abhoy Pada, Formerly Professor of Mathematics, Burdwan Univ.; K-3/6, Karunamayee Estate, Salt Lake, Sector II, Kolkata - 700091; BANDYOPADHYAY, Sanghamitra, Professor & Director, Indian Statistical Institute, 203, BT Road, Kolkata - 700108; BANERJEA, Debabrata, Formerly Sir Rashbehary Ghose Professor of Chemistry,CU; Flat A-4/6,Iswar Chandra Nibas 68/1, Bagmari Road, Kolkata - 700054; BANERJEE, Rabin, Emeritus Professor, SN Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences, Block - JD, Sector - III, Salt Lake, Kolkata - 700098; BANERJEE, Soumitro, Professor, Department of Physical Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education & Research, Mohanpur Campus, WB 741246; BANERJI, Krishna Dulal, Formerly Professor & Head, Chemistry Department, Flat No.C-2,Ramoni Apartments, A/6, P.G. -

Zone Wise List of Fellows & Honorary Fellows

The National Academy of Sciences, India (The Oldest Science Academy of India) Zone wise list of Fellows & Honorary Fellows (2020) 5, Lajpatrai Road, Prayagraj – 211002, UP, India 1 The list has been divided into six zones; and each zone is further having the list of scientists of Physical Sciences and Biological Sciences, separately. 2 The National Academy of Sciences, India 5, Lajpatrai Road, Prayagraj – 211002, UP, India Zone wise list of Fellows Zone 1 (Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, West Bengal, Meghalaya, Assam, Mizoram, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, Manipur and Sikkim) (Section A – Physical Sciences) ACHARYA, Damodar, Chairman, Advisory Board, SOA Deemed to be University, Khandagiri Squre, Bhubanesware - 751030; ACHARYYA, Subhrangsu Kanta, Emeritus Scientist (CSIR), 15, Dr. Sarat Banerjee Road, Kolkata - 700029; ADHIKARI, Satrajit, Sr. Professor of Theoretical Chemistry, School of Chemical Sciences, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, 2A & 2B Raja SC Mullick Road, Jadavpur, Kolkata - 700032; ADHIKARI, Sukumar Das, Formerly Professor I, HRI,Ald; Professor & Head, Department of Mathematics, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda University, Belur Math, Dist Howrah - 711202; BAISNAB, Abhoy Pada, Formerly Professor of Mathematics, Burdwan Univ.; K-3/6, Karunamayee Estate, Salt Lake, Sector II, Kolkata - 700091; BANDYOPADHYAY, Sanghamitra, Professor & Director, Indian Statistical Institute, 203, BT Road, Kolkata - 700108; BANERJEA, Debabrata, Formerly Sir Rashbehary Ghose Professor of Chemistry,CU; Flat A-4/6,Iswar Chandra Nibas 68/1, Bagmari Road, Kolkata - 700054; BANERJEE, Rabin, Emeritus Professor, SN Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences, Block - JD, Sector - III, Salt Lake, Kolkata - 700098; BANERJEE, Soumitro, Professor, Department of Physical Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education & Research, Mohanpur Campus, WB 741246; BANERJI, Krishna Dulal, Formerly Professor & Head, Chemistry Department, Flat No.C-2,Ramoni Apartments, A/6, P.G. -

The Year Book 2019

THE YEAR BOOK 2019 INDIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Bengaluru Postal Address: Indian Academy of Sciences Post Box No. 8005 C.V. Raman Avenue Sadashivanagar Post, Raman Research Institute Campus Bengaluru 560 080 India Telephone : +91-80-2266 1200, +91-80-2266 1203 Fax : +91-80-2361 6094 Email : [email protected], [email protected] Website : www.ias.ac.in © 2019 Indian Academy of Sciences Information in this Year Book is updated up to 22 February 2019. Editorial & Production Team: Nalini, B.R. Thirumalai, N. Vanitha, M. Venugopal, M.S. Published by: Executive Secretary, Indian Academy of Sciences Text formatted by WINTECS Typesetters, Bengaluru (Ph. +91-80-2332 7311) Printed by Lotus Printers Pvt. Ltd., Bengaluru CONTENTS Page Section A: Indian Academy of Sciences Memorandum of Association ................................................... 2 Role of the Academy ............................................................... 4 Statutes .................................................................................. 7 Council for the period 2019–2021 ............................................ 18 Office Bearers ......................................................................... 19 Former Presidents ................................................................... 20 Activities – a profile ................................................................. 21 Academy Document on Scientific Values ................................. 25 The Academy Trust ................................................................. 33 Section B: Professorships -

Effect of Lantana Camara L. Cover on Local Depletion of Tree Population in the Vindhyan Tropical Dry Deciduous Forest of India

Sharma-Raghubanshi: Effect of Lantana camara L. cover on local depletion tree population in a tropical dry deciduous forest - 109 - EFFECT OF LANTANA CAMARA L. COVER ON LOCAL DEPLETION OF TREE POPULATION IN THE VINDHYAN TROPICAL DRY DECIDUOUS FOREST OF INDIA GYAN P. SHARMA* AND A.S. RAGHUBANSHI Department of Botany, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005, India. Fax: 91–542- 2368174. Tel : 91-542-2368399. e-mail: [email protected] (Received 31th March 2006; accepted 15th Apr 2007 ) Abstract. The dry deciduous forest of northern India is being progressively invaded by an alien invasive woody shrub Lantana camara L. (Lantana). The invasion of lantana threatens the survival of many species. This study examines the demographic instability of tree species at different levels of lantana cover. Based on proportion of seedlings of a species in its total population (seedling+sapling+adult), about 39.5% and 60% of total 38 species exhibited local demographic instability at different levels of lantana cover for the first and the second census respectively. This decline in species could be attributed to altered microenvironment (light, pH and temperature) beneath the lantana bushes. The study concludes that the presence of lantana shrub as dense understorey perturbs the seedling recruitment of native tree species in the forest and this leads to differential depletion of native trees. Key words: declining species population, demographic instability, invasion, lantana cover. Introduction Invasion of native communities by exotic species has been among the most intractable ecological problems of recent years (Sharma et al. 2005a). It is a global scale problem experienced by natural ecosystems and is considered as the second largest threat to global biodiversity (Drake et al., 1989). -

S. No. Name (Mr./Ms) Father's/Husband's Name Correspondence Address Date of Birth 1 Ms. Vijayta Raghav Mr. Manmohan Raghav C/O S

PERSONAL ASSISTANT EXAMINATION-2013 List of Eligible Candidates Date of Examination will be intimated later on. S. No. Name (Mr./Ms) Father's/Husband's Name Correspondence Address Date of Birth C/o suresh Kumar, H.NO. 61, 1 Ms. Vijayta Raghav Mr. Manmohan Raghav Village- Motibagh, Nr. 8.09.1985 Nanakpura, N.D. 21. DB-75 A, DDA Flats, Hari 2 Ms. Shalini Sharma Mr. Gaurav Rana 5.11.1984 Nagar, New Delhi -64 D-8/184, East Gokal Pur, 3 Mr. Deepak Kumar Mr. Atal Singh 2.04.1985 Shahdara North East Delhi-94. WZ-303, Sant Garh, St. No. 18, 4 Ms. Surinder Kaur Mr. Daljeet Singh Ground Floor, M.B.S. Nagar, 15.06.1987 Tilak Nagar, New Delhi -18. E-196, Sector-23, Sanjay Nagar, 5 Ms. Jyoti Mr. Rajesh Kumar 18.02.1988 Ghaziabad, UP - 201002. 57-P, DIZ Area, Gole Market 6 Ms. Richa Bajaj Mr. Kamal Bajaj (Raja Bazar), Sec.-4, New Delhi- 5.05.1982 01. H.No. 50, Krishan Kunj colony, 7 Ms. Neetu Kansal Mr. Manish Kansal 18.04.1987 Laxmi Nagar, Delhi - 92. CBI Academy, Hapur Road, 8 Ms. Bharati Sharma Mr. Kamal Prakash Sharma Kamla Nehru Nagar, 22.02.1990 Ghaziabad, U.P.- 201002. H.No. 6612, Radhey Puri, Ext. 9 Ms. Rekha Mahour Mr. Dinesh Kumar 2.07.1989 No. 2, Krishna Nagar, Delhi -51. A/561, Madi Pur Colony, New 10 Ms. Madhu Bala Lt. Mr. Madan Lal 1.11.1986 Delhi - 63. D-106, Gali No. 5, Laxmi Nagar, 11 Ms. Premlata Mr. Dayaram Sharma 28.7.1990 New Delhi-92. -

S. No. ID Full Name Father's Name State District 1 423232

S. No. ID Full Name Father's Name State District 1 423232 AKrishnavamshi Amineni Ravi Chandra Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 2 425654 B ASHOK B Thirupalu Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 3 421719 Bisathi Bharath B Adinarayana Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 4 428717 Jakkalavadiki chikkanna Jakkalavadiki ganganna Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 5 423785 jeevan Kumar B. Bharath Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 6 426534 Johar babu P BHEEMAPPA Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 7 425588 K NAGENDRA PRASAD KADAVAKOLANU NAGANNA Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 8 436056 Kallamadi Navitha Kallamadi Nagalinga Reddy Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 9 424985 Keerthana pavagada Madhusudhana char pavagada Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 10 423351 KORRA REDYA NAIK K.kristaiah naik Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 11 423539 Lokesh B.kondaiah Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 12 422760 Maddy Siva charan M Vijay Kumar Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 13 422565 Malkar Namratha Rao Malkar Ravichandra Rao Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 14 424032 Mamilla Ganesh Mamilla Narayana Swamy Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 15 425956 Mohammad Subahan V Fakroddin V Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 16 428097 NAGARI NAVEEN KUMAR NAGARI THIPPANNA Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 17 421729 NAWAB MEHETAB NASREEN N NAZEER AHMED Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 18 424602 Pallepothula sateesh kumar B.jeevan kumar Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 19 426288 Pedda Yammanuru Sudhakar P.Y.Sudhakar Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 20 422282 Rohith Vasantham Vasantham Madhusudhan Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 21 428633 Sake saisushma S. Narayana swamy Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 22 426347 Sashipreetham M. Radhakrishna Andhra Pradesh -

Details of Unclaimed Deposits / Inoperative Accounts

CITIBANK We refer to Reserve Bank of India’s circular RBI/2014-15/442 DBR.No.DEA Fund Cell.BC.67/30.01.002/2014-15. As per these guidelines, banks are required to display the list of unclaimed deposits/inoperative accounts which are inactive/ inoperative for ten years or more on their respective websites. This is with a view of enabling the public to search the list of account holders by the name of: Account Holder/Signatory Name Address HASMUKH HARILAL 207 WISDEN ROAD STEVENAGE HERTFORDSHIRE ENGLAND UNITED CHUDASAMA KINGDOM SG15NP RENUKA HASMUKH 207 WISDEN ROAD STEVENAGE HERTFORDSHIRE ENGLAND UNITED CHUDASAMA KINGDOM SG15NP GAUTAM CHAKRAVARTTY 45 PARK LANE WESTPORT CT.06880 USA UNITED STATES 000000 VAIDEHI MAJMUNDAR 1109 CITY LIGHTS DR ALISO VIEJO CA 92656 USA UNITED STATES 92656 PRODUCT CONTROL UNIT CITIBANK P O BOX 548 MANAMA BAHRAIN KRISHNA GUDDETI BAHRAIN CHINNA KONDAPPANAIDU DOOR NO: 3/1240/1, NAGENDRA NAGAR,SETTYGUNTA ROAD, NELLORE, AMBATI ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA INDIA 524002 DOOR NO: 3/1240/1, NAGENDRA NAGAR,SETTYGUNTA ROAD, NELLORE, NARESH AMBATI ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA INDIA 524002 FLAT 1-D,KENWITH GARDENS, NO 5/12,MC'NICHOLS ROAD, SHARANYA PATTABI CHETPET,CHENNAI TAMILNADU INDIA INDIA 600031 FLAT 1-D,KENWITH GARDENS, NO 5/12,MC'NICHOLS ROAD, C D PATTABI . CHETPET,CHENNAI TAMILNADU INDIA INDIA 600031 ALKA JAIN 4303 ST.JACQUES MONTREAL QUEBEC CANADA CANADA H4C 1J7 ARUN K JAIN 4303 ST.JACQUES MONTREAL QUEBEC CANADA CANADA H4C 1J7 IBRAHIM KHAN PATHAN AL KAZMI GROUP P O BOX 403 SAFAT KUWAIT KUWAIT 13005 SAJEDAKHATUN IBRAHIM PATHAN AL KAZMI