Dance As Protocol: Social Choreography in Elite Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Types of Dance Styles

Types of Dance Styles International Standard Ballroom Dances Ballroom Dance: Ballroom dancing is one of the most entertaining and elite styles of dancing. In the earlier days, ballroom dancewas only for the privileged class of people, the socialites if you must. This style of dancing with a partner, originated in Germany, but is now a popular act followed in varied dance styles. Today, the popularity of ballroom dance is evident, given the innumerable shows and competitions worldwide that revere dance, in all its form. This dance includes many other styles sub-categorized under this. There are many dance techniques that have been developed especially in America. The International Standard recognizes around 10 styles that belong to the category of ballroom dancing, whereas the American style has few forms that are different from those included under the International Standard. Tango: It definitely does take two to tango and this dance also belongs to the American Style category. Like all ballroom dancers, the male has to lead the female partner. The choreography of this dance is what sets it apart from other styles, varying between the International Standard, and that which is American. Waltz: The waltz is danced to melodic, slow music and is an equally beautiful dance form. The waltz is a graceful form of dance, that requires fluidity and delicate movement. When danced by the International Standard norms, this dance is performed more closely towards each other as compared to the American Style. Foxtrot: Foxtrot, as a dance style, gives a dancer flexibility to combine slow and fast dance steps together. -

2018/19 Hip Hop Rules & Regulations

2018/19 Hip Hop Rules for the New Zealand Schools Hip Hop Competition Presented by the New Zealand Competitive Aerobics Federation 2018/19 Hip Hop Rules, for the New Zealand Schools Hip Hop Championships © New Zealand Competitive Aerobic Federation Page 1 PART 1 – CATEGORIES ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 NSHHC Categories .............................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Hip Hop Unite Categories .................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 NSHHC Section, Division, Year Group, & Grade Overview ................................................................................ 3 1.3.1 Adult Age Division ........................................................................................................................................ 3 1.3.2 Allowances to Age Divisions (Year Group) for NSHHC ................................................................................ 4 1.4 Participation Limit .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Part 2 – COMPETITION REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Performance Area ............................................................................................................................................. -

Urban Street Dance Department

Urban Street Dance Department Divisions and Competition Rules Break Dance Division Urban Street Dance Division Implemented by the WADF Managing Committee January 2020 Artistic Dance Departments, Divisions and Competition Rules WADF Managing Committee Nils-Håkan Carlzon President Irina Shmalko Stuart Saunders Guido de Smet Senior Vice President Executive Secretary Vice President Marian Šulc Gordana Orescanin Roman Filus Vice President Vice President Vice President Page 2 Index Artistic Dance Departments, Divisions and Competition Rules Urban Street Dance Department Section G-2 Urban Street Dance Division Urban Street Dance Competitions Urban Street Urban Street Dance is a broad category that includes a variety of urban styles. The older dance styles that were created in the 1970s include up-rock, breaking, and the funk styles. At the same time breaking was developing in New York, other styles were being created in California. Several street dance styles created in California in the 1970s such as roboting, bopping, hitting, locking, bustin', popping, electric boogaloo, strutting, sac-ing, and dime-stopping. It is historically inaccurate to say that the funk styles were always considered hip-hop. "Hip-Hop Dance" became an umbrella term encompassing all of these styles. Tempo of the Music: Tempo: 27 - 28 bars per minute (108 - 112 beats per minute) Characteristics and Movement: Different new dance styles, such as Quick Popping Crew, Asian style, African style, Hype Dance, New-Jack-Swing, Popping & Locking, Jamming, etc., adding creative elements such as stops, jokes, flashes, swift movements, etc. Some Electric and Break movements can be performed but should not dominate. Floor figures are very popular but should not dominate the performance. -

Musica House Dance 2014

Musica house dance 2014 The Best New Best Dance Music || Electro & House Dance Club Mix || Vol (Electro House. Best dance music new electro house The latest in electronic dance music. Get the latest from. The Best Electronic Dance Music Sessions (Electro House, Progressive House, Tech House, EDM). Always. Best Dance Music Electro House Dance Club Mix. ▻More Free Music: See als our. Best Dance Music Electro House Dance Club Mix Tracklist: 1. Phunk Investigation - Let The Bass Kick. More Videos from Best Dance Music | Electro & House. CLUB MUSIC MIXES Free Download: ▸Follow us on Instagram for Models: https://www. TO CHANNEL!!! SEGUIMI ANCHE SU FACEBOOK More Free Music: Facebook: Create your own Electro House - EDM. It's been an eventful year in dance music, to say the least. Kudos to French house wunderkind Wilfred Giroux for being the tough-love friend. CLUB & DANCE songs New House Music Mix [Club Party Lover's] Maximal Electro House Stream New Best Dance Music Electro & House Dance Club Mix By Gerrard #1 by Anthony Gerrard from desktop or your mobile device. Listen to the best Electro house dance club music track remix mix shows. Romyyca89 @ Night Party Mix _Vol.1_-_(Dance-Club Edition). Free with Apple Music subscription. Just Dance - 50 EDM Club Electro House Hits. Various Artists Roar (Glee Free Dance Edit). Electro House Special Dance Mix Electro House Progressive usa, axwell, hits , great club, bass, collection, love house music. Vários/House - Best of Dance (2CD). Compre as novidades de música na House music is a genre of electronic music created by club DJs and music producers in House music developed in Chicago's underground dance club culture in the early s, as DJs (re-issue of a November article). -

Streetdance and Hip Hop - Let's Get It Right!

STREETDANCE AND HIP HOP - LET'S GET IT RIGHT! Article by David Croft, Freelance Dance Artist OK - so I decided to write this article after many years studying various styles of Street dance and Hip Hop, also teaching these styles in Schools, Dance schools and in the community. Throughout my years of training and teaching, I have found a lack of understanding, knowledge and, in some cases, will, to really search out the skills, foundation and blueprint of these dances. The words "Street Dance" and "Hip Hop" are widely and loosely used without a real understanding of what they mean. Street Dance is an umbrella term for various styles including Bboying or breakin (breakin is an original Hip Hop dance along with Rockin and Party dance – the word break dance did not exist in the beginning, this was a term used by the media, originally it was Bboying. (Bboy, standing for Break boy, Beat boy or Bronx boy)…….for more click here Conquestcrew Popping/Boogaloo Style was created by Sam Soloman and Popping technique involves contracting your muscles to the music using your legs, arms, chest and neck. Boogaloo has a very funky groove constantly using head and shoulders. It also involves rolling the hips and knees. Locking was created by Don Campbell. This involves movements like wrist twirls, points, giving himself “5”, locks (which are sharp stops), knee drops and half splits. (Popping/Boogaloo and Locking are part of the West Coast Funk movement ). House Dance and Hip Hop. With Hip Hop coming out of the East Coast (New York) and West Coast Funk from the west (California) there was a great collaboration in cultures bringing the two coasts together. -

B-Girl Like a B-Boy Marginalization of Women in Hip-Hop Dance a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Division of the University of H

B-GIRL LIKE A B-BOY MARGINALIZATION OF WOMEN IN HIP-HOP DANCE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN DANCE DECEMBER 2014 By Jenny Sky Fung Thesis Committee: Kara Miller, Chairperson Gregg Lizenbery Judy Van Zile ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give a big thanks to Jacquelyn Chappel, Desiree Seguritan, and Jill Dahlman for contributing their time and energy in helping me to edit my thesis. I’d also like to give a big mahalo to my thesis committee: Gregg Lizenbery, Judy Van Zile, and Kara Miller for all their help, support, and patience in pushing me to complete this thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………… 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 1 2. Literature Review………………………………………………………………… 6 3. Methodology……………………………………………………………………… 20 4. 4.1. Background History…………………………………………………………. 24 4.2. Tracing Female Dancers in Literature and Film……………………………... 37 4.3. Some History and Her-story About Hip-Hop Dance “Back in the Day”......... 42 4.4. Tracing Females Dancers in New York City………………………………... 49 4.5. B-Girl Like a B-Boy: What Makes Breaking Masculine and Male Dominant?....................................................................................................... 53 4.6. Generation 2000: The B-Boys, B-Girls, and Urban Street Dancers of Today………………...……………………………………………………… 59 5. Issues Women Experience…………………………………………………….… 66 5.1 The Physical Aspect of Breaking………………………………………….… 66 5.2. Women and the Cipher……………………………………………………… 73 5.3. The Token B-Girl…………………………………………………………… 80 6.1. Tackling Marginalization………………………………………………………… 86 6.2. Acknowledging Discrimination…………………………………………….. 86 6.3. Speaking Out and Establishing Presence…………………………………… 90 6.4. Working Around a Man’s World…………………………………………… 93 6.5. -

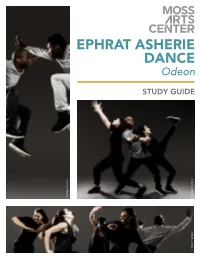

EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE Odeon

EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE Odeon STUDY GUIDE ©Matthew Murphy ©Matthew Murphy ©Matthew Murphy Wednesday, March 31, 2021, 10 AM EDT PROGRAM Odeon Choreographer: Ephrat Asherie, in collaboration with Ephrat Asherie Dance Music: Ernesto Nazareth Musical Direction: Ehud Asherie Lighting Design: Kathy Kaufmann Costume Design: Mark Eric We gratefully acknowledge and thank the Joyce Theater’s School & Family Programs for generously allowing the Moss Arts Center’s use and adaptation of its Ephrat Asherie Dance Odeon Resource and Reference Guide. Heather McCartney, director | Rachel Thorne Germond, associate EPHRAT ASHERIE DANCE “Ms. Asherie’s movement phrases—compact bursts of choreography with rapid-fire changes in rhythm and gestural articulation—bubble up and dissipate, quickly paving the way for something new.” –The New York Times THE COMPANY Ephrat Asherie Dance (EAD) is a dance company rooted in Black and Latinx vernacular dance. Dedicated to exploring the inherent complexities of various street and club dances, including breaking, hip-hop, house, and vogue, EAD investigates the expansive narrative qualities of these forms as a means to tell stories, develop innovative imagery, and find new modes of expression. EAD’s first evening-length work,A Single Ride, earned two Bessie nominations in 2013 for Outstanding Emerging Choreographer and Outstanding Sound Design by Marty Beller. The company has presented work at Apollo Theater, Columbia College, Dixon Place, FiraTarrega, Works & Process at the Guggenheim, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, the Joyce Theater, La MaMa, River to River Festival, New York Live Arts, Summerstage, and The Yard, among others. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie is a New York City-based b-girl, performer, choreographer, and director and a 2016 Bessie Award Winner for Innovative Achievement in Dance. -

Dce 202 Hu.Pdf

Arizona State University Criteria Checklist for HUMANITIES, FINE ARTS AND DESIGN [HU] Rationale and Objectives The humanities disciplines are concerned with questions of human existence and meaning, the nature of thinking and knowing, with moral and aesthetic experience. The humanities develop values of all kinds by making the human mind more supple, critical, and expansive. They are concerned with the study of the textual and artistic traditions of diverse cultures, including traditions in literature, philosophy, religion, ethics, history, and aesthetics. In sum, these disciplines explore the range of human thought and its application to the past and present human environment. They deepen awareness of the diversity of the human heritage and its traditions and histories and they may also promote the application of this knowledge to contemporary societies. The study of the arts and design, like the humanities, deepens the student’s awareness of the diversity of human societies and cultures. The fine arts have as their primary purpose the creation and study of objects, installations, performances and other means of expressing or conveying aesthetic concepts and ideas. Design study concerns itself with material objects, images and spaces, their historical development, and their significance in society and culture. Disciplines in the fine arts and design employ modes of thought and communication that are often nonverbal, which means that courses in these areas tend to focus on objects, images, and structures and/or on the practical techniques and historical development of artistic and design traditions. The past and present accomplishments of artists and designers help form the student’s ability to perceive aesthetic qualities of art work and design. -

Social Media Analytics for Youtube Comments: Potential and Limitations1 Mike Thelwall

Social Media Analytics for YouTube Comments: Potential and Limitations1 Mike Thelwall School of Mathematics and Computing, University of Wolverhampton, UK The need to elicit public opinion about predefined topics is widespread in the social sciences, government and business. Traditional survey-based methods are being partly replaced by social media data mining but their potential and limitations are poorly understood. This article investigates this issue by introducing and critically evaluating a systematic social media analytics strategy to gain insights about a topic from YouTube. The results of an investigation into sets of dance style videos show that it is possible to identify plausible patterns of subtopic difference, gender and sentiment. The analysis also points to the generic limitations of social media analytics that derive from their fundamentally exploratory multi-method nature. Keywords: social media analytics; YouTube comments; opinion mining; gender; sentiment; issues Introduction Questionnaires, interviews and focus groups are standard social science and market research methods for eliciting opinions from the public, service users or other specific groups. In industry, mining social media for opinions expressed in public seems to be standard practice with commercial social media analytics software suites that include an eclectic mix of data mining tools (e.g., Fan & Gordon, 2014). Within academia, there is also a drive to generate effective methods to mine the social web (Stieglitz, Dang-Xuan, Bruns, & Neuberger, 2014). From a research methods perspective, there is a need to investigate the generic limitations of new methodological approaches. Many existing social research techniques have been adapted for the web, such as content analysis (Henrich & Holmes, 2011), ethnography (Hine, 2000), surveys (Crick, 2012; Harrison, Wilding, Bowman, Fuller, Nicholls, et al. -

Baby Raves: Youth, Adulthood and Ageing in Contemporary British EDM Culture

Baby Raves: Youth, Adulthood and Ageing in Contemporary British EDM Culture Feature Article Zoe Armour De Montfort University (UK) Abstract This article begins with a reconsideration of the parameters ofage in translocal EDM sound system and (super)club culture through the conceptualisation of a fluid multigenerationality in which attendees at EDM-events encompass a spectrum of ages from 0–75 years. Since the 1980s, it remains the case that the culture is fuelled through a constant influx of newcomers who are predominantly emerging youth, yet there are post-youth members in middle adulthood and later life that are also a growing body that continues to attend EDM-events. In this context, the baby rave initiative (2004–present) has capitalised on a gap in the family entertainment market and created a new chapter in (super)club and festival culture. I argue that the event is a catalyst for live heritage in which the accompanying children (aged from 0–12 years) temporarily become the beneficiaries of their parent’s attendee heritage and performance of an unauthored heritage. Keywords: fluid multigenerationality, EDM-family, baby rave, live heritage, unauthored heritage Zoe Armour is completing a PhD in electronic dance music culture. Her work is interdisciplinary and draws from the fields of cultural sociology, popular music, memory studies, media and communication and film. She is the author of two book chapters on Ageing Clubbers and the Internet and the British Free Party Counterculture in the late 1990s. She is a member of the Media Discourse Centre, IASPM and follows the group for Subcultures, Popular Music and Social Change. -

Interactive Animation Dance Game

Interactive Dance Game Name:_______________ Interactive: interacting with a human user, often in a conversational way, to obtain data or commands and to give immediate results or updated information. Dance: to move one's feet or body, or both, rhythmically in a pattern of steps, especially to the accompaniment of music. STEP ONE: RESEARCH at least 3 Dance Styles/Moves by looking at the attached “Dance Styles Categories” sheet and then ANSWER the attached sheet “ Researching Dance Styles & Moves.” STEP TWO: DRAW 3 conceptual designs of possible character designs for your one dance figure. STEP THREE: SCAN your character design into the computer and/or create digitally in Adobe Photoshop or directly in Macromedia Flash. Character Design Graphic Names STEP FOUR: BREAK UP the pieces of your digital character design like the above Character Design Graphic Names . If creating in Adobe Photoshop ensure you save each piece of your digital character with a TRANSPARENT BACKGROUND and save each separately as PSD files . STEP FIVE: IMPORT your character design (approved by teacher) into the program Macromedia Flash – piece by piece by OPENING Macromedia Flash then SELECT from the top of menu -> WINDOW -> SHOW LIBRARY -> STEP SIX: DOUBLE CLICK on the specific Character Design Graphic piece you want to IMPORT (SEE the above photo for specific names of body parts i.e. right arm upper graphic) STEP SEVEN: DELETE the template graphic part and PASTE or choose FILE IMPORT in the one you designed on paper or Adobe Photoshop . (head etc..) STEP EIGHT: RESIZE specific Character Design graphic pieces by RIGHT MOUSE CLICKing on the graphic and choose FREE TRANFORM to scale up or down. -

Injury Profile of Hip-Hop Dancers

Injury Profile of Hip-Hop Dancers Olga Tjukov, MA, Tobias Engeroff, PhD, Lutz Vogt, PhD, Winfried Banzer, PhD, MD, and Daniel Niederer, PhD Abstract dancers only involved the lower extremi- Hip-hop is characterized by moves This study assessed the injury incidence, ties. In house, the lower extremities were such as bouncing the body, bending mechanisms, and associated potential risk affected most frequently, followed by the the knees, jumping, turning, twisting, factors for hip-hop, popping, locking, trunk. A total of 65.3% of the dancers isolated extremity movements, and an house, and breaking dance styles. Data experienced time loss, with a duration of extreme involvement of the torso. The were collected from June to November 12.7 ± 21.3 weeks. Breakers experience significantly more injuries than dancers of characteristics of popping are short 2015. The retrospective cohort study and fast muscle contractions, which included 146 dancers (female: N = 67; the other styles. Injury risk among dancers of all the styles studied can be considered are performed with different body age = 20 ± 4.2 years; males: N = 79; age parts to the rhythms of the music. The = 22.9 ± 5.8 years) who completed a low compared to soccer players, swim- mers, and long-distance runners. dancer looks robotic and can incorpo- questionnaire that collected data concern- 6 ing training hours, injuries, self-reported rate wave and illusion techniques. In the dance style locking, many basic injury causes, treatment, and recovery ompetitive dancing has been movements are executed with the time over the last 5 years. For the last 5 associated with a high risk arms and wrists, which are “locked” years, 52% (N = 76) of the dancers re- of injury.1 While injuries in ported 159 injuries and, in the year prior or paused to point.