The Other Civil War : Lincoln and the Indians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edmund Rice (1638) Association Newsletter

EDMUND RICE (1638) ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTER Published Summer, Fall, Winter, Spring by the Edmund Rice (1638) Association, 24 Buckman Dr., Chelmsford MA 01824-2156 The Edmund Rice (1638) Association was established in 1851 and incorporated in 1934 to encourage antiquarian, genealogical, and historical research concerning the ancestors and descendants of Edmund Rice who settled in Sudbury, Massachusetts in 1638, and to promote fellowship among its members and friends. The Association is an educational, non-profit organization recognized under section 501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Edmund Rice (1638) Assoc., Inc. NONPROFIT ORG 24 Buckman Drive US POSTAGE Chelmsford, MA 01824-2156 PAID Return Postage Guarantee CHELMSFORD MA PERMIT NO. 1055 1 Edmund Rice (1638) Association Newsletter _____________________________________________________________________________________ 24 Buckman Dr., Chelmsford MA 01824 Vol. 79, No. 1 Winter 2005 _____________________________________________________________________________________ President's Column Inside This Issue Our Rice Reunion 2004 seemed to have attracted cousins who normally Editor’s Column p. 2 don’t attend, so the survey instigated by George Rice has proven particularly useful. One theme reunion attendees asked for appears to be a desire to hear more history of Database Update p. 5 our early Puritan forefathers. US Census Online p. 6 To that end, we have found an expert in the history of the Congregationalists Family Thicket V p. 7 who succeeded the Puritans. He is Rev. Mark Harris who, among other things, teaches at the Andover Newton Theological Seminary. He will speak at our Annual Meeting Genetics Report p. 8 2005 on the evolution of Puritans from the 1700s, where Francis Bremer left off, to the Rices In Kahnawake p. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

Vol. 01/ 6 (1916)

REVIEWS OF BOOKS History of Stearns County, Minnesota. By WILLIAM BELL MITCHELL. In two volumes. (Chicago, H. C. Cooper Jr. and Company, 1915. xv, xii, 1536 p. Illustrated) These two formidable-looking volumes, comprising some fif teen hundred pages in all, are an important addition to the literature of Minnesota local history. The author is himself a pioneer. Coming to Minnesota in 1857, he worked as surveyor, teacher, and printer until such time as he was able to acquire the St. Cloud Democrat. He later changed the name of the paper to the St. Cloud lournal, and, after his purchase of the St. Cloud Press in 1876, consolidated the two under the name St. Cloud Journal-Press, of which he remained editor and owner until 1892. During this period he found time also to discharge the duties of receiver of the United States land office at St. Cloud, and to serve as member of the state normal board. It would appear, then, that Mr. Mitchell, both by reason of his long resi dence in Stearns County and of his editorial experience, was preeminently fitted for the task of writing the volumes under review. Moreover, he has had the assistance of many of the prominent men of the county in preparing the general chapters of the work. Among these may be noted chapters 2-6, dealing with the history of Minnesota as a whole during the pre-territorial period, by Dr. P. M. Magnusson, instructor in history and social science in the St. Cloud Normal; a chapter on "The Newspaper Press" by Alvah Eastman of the St. -

H. Doc. 108-222

1776 Biographical Directory York for a fourteen-year term; died in Bronx, N.Y., Decem- R ber 23, 1974; interment in St. Joseph’s Cemetery, Hacken- sack, N.J. RABAUT, Louis Charles, a Representative from Michi- gan; born in Detroit, Mich., December 5, 1886; attended QUINN, Terence John, a Representative from New parochial schools; graduated from Detroit (Mich.) College, York; born in Albany, Albany County, N.Y., October 16, 1836; educated at a private school and the Boys’ Academy 1909; graduated from Detroit College of Law, 1912; admitted in his native city; early in life entered the brewery business to the bar in 1912 and commenced practice in Detroit; also with his father and subsequently became senior member engaged in the building business; delegate to the Democratic of the firm; at the outbreak of the Civil War was second National Conventions, 1936 and 1940; delegate to the Inter- lieutenant in Company B, Twenty-fifth Regiment, New York parliamentary Union at Oslo, Norway, 1939; elected as a State Militia Volunteers, which was ordered to the defense Democrat to the Seventy-fourth and to the five succeeding of Washington, D.C., in April 1861 and assigned to duty Congresses (January 3, 1935-January 3, 1947); unsuccessful at Arlington Heights; member of the common council of Al- candidate for reelection to the Eightieth Congress in 1946; bany 1869-1872; elected a member of the State assembly elected to the Eighty-first and to the six succeeding Con- in 1873; elected as a Democrat to the Forty-fifth Congress gresses (January 3, 1949-November 12, 1961); died on No- and served from March 4, 1877, until his death in Albany, vember 12, 1961, in Hamtramck, Mich; interment in Mount N.Y., June 18, 1878; interment in St. -

H. Doc. 108-222

THIRTY-NINTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1865, TO MARCH 3, 1867 FIRST SESSION—December 4, 1865, to July 28, 1866 SECOND SESSION—December 3, 1866, to March 3, 1867 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1865, to March 11, 1865 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—ANDREW JOHNSON, 1 of Tennessee PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—LAFAYETTE S. FOSTER, 2 of Connecticut; BENJAMIN F. WADE, 3 of Ohio SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—JOHN W. FORNEY, of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—GEORGE T. BROWN, of Illinois SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—SCHUYLER COLFAX, 4 of Indiana CLERK OF THE HOUSE—EDWARD MCPHERSON, 5 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—NATHANIEL G. ORDWAY, of New Hampshire DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—IRA GOODNOW, of Vermont POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—JOSIAH GIVEN ALABAMA James Dixon, Hartford GEORGIA SENATORS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES Vacant Vacant Henry C. Deming, Hartford REPRESENTATIVES 6 Samuel L. Warner, Middletown REPRESENTATIVES Vacant Augustus Brandegee, New London Vacant John H. Hubbard, Litchfield ARKANSAS ILLINOIS SENATORS SENATORS Vacant DELAWARE Lyman Trumbull, Chicago Richard Yates, Jacksonville REPRESENTATIVES SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES Vacant Willard Saulsbury, Georgetown George R. Riddle, Wilmington John Wentworth, Chicago CALIFORNIA John F. Farnsworth, St. Charles SENATORS REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE Elihu B. Washburne, Galena James A. McDougall, San Francisco John A. Nicholson, Dover Abner C. Harding, Monmouth John Conness, Sacramento Ebon C. Ingersoll, Peoria Burton C. Cook, Ottawa REPRESENTATIVES FLORIDA Henry P. H. Bromwell, Charleston Donald C. McRuer, San Francisco Shelby M. Cullom, Springfield William Higby, Calaveras SENATORS Lewis W. Ross, Lewistown John Bidwell, Chico Vacant 7 Anthony Thornton, Shelbyville Vacant 8 Samuel S. -

Guide to a Microfilm Edition of the Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records

-~-----', Guide to a Microfilm Edition of The Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records Helen McCann White Minnesota Historical Society . St. Paul . 1974 -------~-~~~~----~! Copyright. 1974 @by the Minnesota Historical Society Library of Congress Catalog Number:74-10395 International Standard Book Number:O-87351-091-7 This pamphlet and the microfilm edition of the Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records which it describes were made possible by a grant of funds from the National Historical Publications Commission to the Minnesota Historical Society. Introduction THE PAPERS AND OFFICIAL RECORDS of Alexander Ramsey are the sixth collection to be microfilmed by the Minnesota Historical Society under a grant of funds from the National Historical Publications Commission. They document the career of a man who may be charac terized as a 19th-century urban pioneer par excellence. Ramsey arrived in May, 1849, at the raw settlement of St. Paul in Minne sota Territory to assume his duties as its first territorial gov ernor. The 33-year-old Pennsylvanian took to the frontier his family, his education, and his political experience and built a good life there. Before he went to Minnesota, Ramsey had attended college for a time, taught school, studied law, and practiced his profession off and on for ten years. His political skills had been acquired in the Pennsylvania legislature and in the U.S. Congress, where he developed a subtlety and sophistication in politics that he used to lead the development of his adopted city and state. Ram sey1s papers and records reveal him as a down-to-earth, no-non sense man, serving with dignity throughout his career in the U.S. -

Congressional Record-House. March 16

Lt212 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. MARCH 16, is not a disposition, uut is a permanent holding. I will resume Maine, Mr. PoiNDEXTER, Mr. S'FERLING, Mr. THoMPsoN, Mr. tl1e <lis eu ~ si on of the provisions of the bill to-morrow. AsHURST, and Mr. PAGE. Mr. Sl\IOOT. I inquire if the Senator from Colorado desires PROPOSED RECESS. to proceed f-urther thls afternoon? The hour is rather late. J'IJr. SHAFROTH. I wonld prefer, if it be agreeable to the Mr. MYERS. I move that the Senate take a recess until to· Sennte, to suspend at this time and yield for an adjournment. morrow at 12 o'clock noon. MILITARY PREPAREDNESS. J\.Ir. CHAMBERLAIN. I hope the Senator will .not moy to take a recess. I should like very much to report the Army reor· 1\Ir. McCUMBER. I desire to give notice that to-morrow ganization bill to-morrow, and if the1·e is a single objection to morning, immediately after the close of the routine morning it I can no.t do so if we have a :recess. business, with the permission of the Senate, I shall submit Mr. MYERS. I do not think any Senator will object to the some remarks on certain phases of the so-called preparedness Senato1· making the report ; but if the Senator thinks that a program. recess might interfere with the presentation of the report, I l\1r. l\IYERS. Mr. President, in relation to what the Senator will withdraw the motion. from North Dakota has just said, I favor taking a recess until Mr. -

William Windom, 1827-1890

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com W9323 S'^r-Si-^Sj 'WmM ';'.• H [ftf *Et5*ryg£ ;".it''iV3Frf;f r^rtrrr. tfagtc jig |UUUBfl ^SfHc ij|f& J§2| ' UlitfSQlS BS393 ■ ' ■■rai M59E1 0T I J 1967 WILLIAM WIHD0M 1827 - 1890 HIS PUBLIC SERVICES BY GRACE AHUE WRIGHT A THESIS SUBMITTED F0R THE DEGREE 0F MASTER OF ARTS U1TIYERSITY OF WISC0USIH 1911 399201 OCT 1 0 1933 TABLE OF C0NTENTS page CHAPTER 1 Introduotion--3iographical Sketch - - 1 CHAPTER 11 Piiblio Lands ------------- 6 CHAPTER 111 Indian Affairs ------ -- 17 CHAPTER 1V Transportation ------------- 30 CHAPTER V Finanoe ----------------- 61 CHAPTER V1 Personality and Character -------- 83 CHAPTER 1 IMR0DUCTI0JJ AJJD BI0GRAPHIGAI SKETCH The years from the end of the Revolutionary War to the election of Washington are known as the "Critical Period," because our national life swung in the balance dur ing that time. To one other period may this same name be ap plied, when for a seoond time the Union was threatened with disolution and destruction. Surely the twenty years between 1860 and 1880 were fraught with many danger of many kinds. In the first critical period it was the sane , sound common sense and the judgment and foresight of our national leaders, the makers of our constitution, that saved our bark from shipwreok on the rocks of State Sovereignty and commercial rivalry. In the second case the exceptional leadership of Lincoln was not alone responsible far our weathering the storm of Civil War- -we owe much to the wisdom of our Congress especially in solving the problems that followed the war. -

Fifty Years in the Northwest: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Fifty years in the Northwest L34 3292 1 W. H. C. Folsom FIFTY YEARS IN THE NORTHWEST. WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND APPENDIX CONTAINING REMINISCENCES, INCIDENTS AND NOTES. BY W illiam . H enry . C arman . FOLSOM. EDITED BY E. E. EDWARDS. PUBLISHED BY PIONEER PRESS COMPANY. 1888. G.1694 F606 .F67 TO THE OLD SETTLERS OF WISCONSIN AND MINNESOTA, WHO, AS PIONEERS, AMIDST PRIVATIONS AND TOIL NOT KNOWN TO THOSE OF LATER GENERATION, LAID HERE THE FOUNDATIONS OF TWO GREAT STATES, AND HAVE LIVED TO SEE THE RESULT OF THEIR ARDUOUS LABORS IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE WILDERNESS—DURING FIFTY YEARS—INTO A FRUITFUL COUNTRY, IN THE BUILDING OF GREAT CITIES, IN THE ESTABLISHING OF ARTS AND MANUFACTURES, IN THE CREATION OF COMMERCE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE, THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR, W. H. C. FOLSOM. PREFACE. Fifty years in the Northwest http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.01070 Library of Congress At the age of nineteen years, I landed on the banks of the Upper Mississippi, pitching my tent at Prairie du Chien, then (1836) a military post known as Fort Crawford. I kept memoranda of my various changes, and many of the events transpiring. Subsequently, not, however, with any intention of publishing them in book form until 1876, when, reflecting that fifty years spent amidst the early and first white settlements, and continuing till the period of civilization and prosperity, itemized by an observer and participant in the stirring scenes and incidents depicted, might furnish material for an interesting volume, valuable to those who should come after me, I concluded to gather up the items and compile them in a convenient form. -

Congressional Record-Senate. 1113

1879. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 1113 The vote being announced, Mr. GARFillLD said: I raise the point that no quorum is pre8ent. IN SENATE. This question is too important to be decided by less than a quorum. SATURDAY, February 8, 1879. The.SPEAKER. No quorum bas voted. Prayer by the Cha~lain, Rev. BYRON SUNDERLAND, D. D. Mr. P .A.TTERSON, of Colorado. I move that the House now ad- The Journal of yesterday's proceedings was read and approved. journ. • The question being taken, there were-ayes 54, noes 44. CREDENTIALS. Mr. McKENZIE. I call for the yeas and nays. Mr. GARL~D presented the credentials of JAMEs D. WA.LKER., Mr. STEPHENS, of Georgia. I hope the gentleman will withdraw chosen by the Legislature of Arkansas a Senator from that State for the demand for the yeas and nays. There is no quorum present, and the term beginning March 4, 1879 ; which were read. and ordered to we may as well adjourn. be filed. The yeas and nays were not ordered. EXECUTIVE COMMUNICATIONS. So the motion to adjourn was agreed to; and accordingly (at nine The VICE-PRESIDENT laid before the Senate a. message from the o'clock and forty minutes p. m.) tlie House adjourned. President of the United States, submitting a report of the commis sion appointed under the provisions of theaot approvedMay 3,1878, entitled ''An act autborizin~ the President of the Un,ited States to PETITIONS, ETd. make certain negotiations With the Ute Indians in the State of Col· The following petitions, &c., were presented at the Clerk's desk, orado ; which was ordered to lie on the table and be printed. -

The Birth of Minnesota / William E. Lass

pages 256-266 8/20/07 11:39 AM Page 267 TheThe BBIRTHIRTH ofof MMINNESOTAINNESOTA tillwater is known as the WILLIAM E. LASS birthplace of Minnesota, primarily because on August 26, 1848, invited Sdelegates to the Stillwater Conven- tion chose veteran fur trader Henry Hastings Sibley to press Minnesota’s case for territorial status in Con- gress. About a week and a half after the convention, however, many of its members were converted to the novel premise that their area was not really Minnesota but was instead still Wisconsin Territory, existing in residual form after the State of Wisconsin had been admitted to the union in May. In a classic case of desperate times provoking bizarre ideas, they concluded that John Catlin of Madison, the last secretary of the territory, had succeeded to the vacant territorial governorship and had the authority to call for the Dr. Lass is a professor of history at Mankato State University. A second edi- tion of his book Minnesota: A History will be published soon by W. W. Norton. SUMMER 1997 267 MH 55-6 Summer 97.pdf 37 8/20/07 12:28:09 PM pages 256-266 8/20/07 11:39 AM Page 268 election of a delegate to Congress. As a willing, Stillwater–St. Paul area. The politics of 1848–49 if not eager, participant in the scheme, Catlin related to the earlier dispute over Wisconsin’s journeyed to Stillwater and issued an election northwestern boundary. Minnesota had sought proclamation. Then, on October 30, the so- an identity distinct from Wisconsin beginning called Wisconsin Territory voters, who really with the formation of St. -

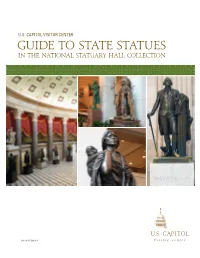

Guide to State Statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection

U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER GUide To STATe STATUes iN The NATioNAl STATUArY HAll CollecTioN CVC 19-107 Edition V Senator Mazie Hirono of Hawaii addresses a group of high school students gathered in front of the statue of King Kamehameha in the Capitol Visitor Center. TOM FONTANA U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER GUide To STATe STATUes iN The NATioNAl STATUArY HAll CollecTioN STATE PAGE STATE PAGE Alabama . 3 Montana . .28 Alaska . 4 Nebraska . .29 Arizona . .5 Nevada . 30 Arkansas . 6 New Hampshire . .31 California . .7 New Jersey . 32 Colorado . 8 New Mexico . 33 Connecticut . 9 New York . .34 Delaware . .10 North Carolina . 35 Florida . .11 North Dakota . .36 Georgia . 12 Ohio . 37 Hawaii . .13 Oklahoma . 38 Idaho . 14 Oregon . 39 Illinois . .15 Pennsylvania . 40 Indiana . 16 Rhode Island . 41 Iowa . .17 South Carolina . 42 Kansas . .18 South Dakota . .43 Kentucky . .19 Tennessee . 44 Louisiana . .20 Texas . 45 Maine . .21 Utah . 46 Maryland . .22 Vermont . .47 Massachusetts . .23 Virginia . 48 Michigan . .24 Washington . .49 Minnesota . 25 West Virginia . 50 Mississippi . 26 Wisconsin . 51 Missouri . .27 Wyoming . .52 Statue photography by Architect of the Capitol The Guide to State Statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection is available as a free mobile app via the iTunes app store or Google play. 2 GUIDE TO STATE STATUES IN THE NATIONAL STATUARY HALL COLLECTION U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER AlabaMa he National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol is comprised of statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history. The entire collection now consists of 100 statues contributed by 50 states.