Elisha Jones, Weston Loyalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class of 2022 PGY II – Current 2Nd Years

Class of 2022 PGY II – Current 2nd Years I was born and raised in the Bay Area and went to Vassar College, where I majored in political science and drama. After studying public health abroad, I began to see clearly how medicine could be used as a vehicle for social justice. I went on to complete a postbac in Baltimore and then worked with the Transitions Clinic Network to care for patients who had recently been released from prison. At UC Irvine School of Medicine, I was involved in leadership of a syringe exchange and starting projects in the local jail system. I chose to go into family medicine because it will best allow me to help patients and communities combat and prevent illness. When the time comes to lobby for policies Birnbaum, Nathan Jacob that positively impact society’s health, being a family University of California Irvine, physician will best equip me to advocate for my patients. School of Medicine My interests include addiction, reentry medicine, reproductive justice, and health policy. I chose UNM for its broad scope of training, commitment to community health, leadership in addiction, and its role as academic safety-net system. I am incredibly excited to move to Albuquerque with my co-FM resident and wife Orli! Born and raised in Albuquerque, I have grown up grateful for sunshine and the beauty of blending cultures, languages, and people from different walks of life. I attended the College of William and Mary in Virginia for college. Afterwards, I returned to Albuquerque where I eventually was fortunate to attend medical school at UNM. -

Guilt No. 48 Genesis 42

From The Pulpit Of Guilt No. 48 Genesis 42 - 44 November 16, 2008 Series: Genesis Nathan Carter Text When Jacob learned that there was grain in Egypt, he said to his sons, "Why do you just keep looking at each other?" 2 He continued, "I have heard that there is grain in Egypt. Go down there and buy some for us, so that we may live and not die." 3 Then ten of Joseph's brothers went down to buy grain from Egypt. 4 But Jacob did not send Benjamin, Joseph's brother, with the others, because he was afraid that harm might come to him. 5 So Israel's sons were among those who went to buy grain, for the famine was in the land of Canaan also. 6 Now Joseph was the governor of the land, the one who sold grain to all its people. So when Joseph's brothers arrived, they bowed down to him with their faces to the ground. 7 As soon as Joseph saw his brothers, he recognized them, but he pretended to be a stranger and spoke harshly to them. "Where do you come from?" he asked. "From the land of Canaan," they replied, "to buy food." 8 Although Joseph recognized his brothers, they did not recognize him. 9 Then he remembered his dreams about them and said to them, "You are spies! You have come to see where our land is unprotected." 10 "No, my lord," they answered. "Your servants have come to buy food. 11 We are all the sons of one man. -

Your God Is Too Silent Rich Nathan October 24-25, 2015 Your God Is Too…Series Psalm 1

Your God Is Too Silent Rich Nathan October 24-25, 2015 Your God Is Too…Series Psalm 1 How many of you are facing a major decision in the next 6 months, a decision which will significantly impact the course of your life? For example, if you are a young person you may be trying to decide whether you ought to go to college or, perhaps, join the military, or take a year off and travel, or do ministry. If you choose college, which college should you go to? Should you start off in a community college; should you pursue a four year degree? And where will that be? How much debt should you take on? When you go to college, what should your major be? Some of you already have Bachelor’s degrees and are thinking about enrolling in a Master’s program, or pursuing your doctorate. Or many of you are applying for jobs, or thinking about leaving your current employment because you are unhappy. Some of you may be deciding whether or not to purchase a home, or to build a home. Should you get married? Who should you marry? Should you have a child? Should you have another child? Maybe you’re in a situation where there are medical risks if you have a child. Should you try anyway? For some of you, your life-changing decision may be about bringing a foster child into your home. Or choosing to adopt a child. And certainly it is not just young adults who are facing major decisions that may significantly impact the course of our lives. -

Old Testament Order of Prophets

Old Testament Order Of Prophets Dislikable Simone still warbling: numbing and hilar Sansone depopulating quite week but immerse her alwaysthrust deliberatively. dippiest and sugar-caneHiro weep landward when discovers if ingrained some Saunder Neanderthaloid unravelling very or oftener finalizing. and Is sillily? Martino And trapped inside, is the center of prophets and the terms of angels actually did not store any time in making them The prophets also commanded the neighboring nations to live in peace with Israel and Judah. The people are very easygoing and weak in the practice of their faith. They have said it places around easter time to threaten judgment oracles tend to take us we live in chronological positions in a great fish. The prophet describes a series of calamities which will precede it; these include the locust plague. Theologically it portrays a cell in intimate relationship with the natural caution that. The band Testament books of the prophets do not appear white the Bible in chronological order instead and are featured in issue of size Prophets such as Isaiah. Brief sight Of Roman History from Her Dawn if the First Punic War. He embodies the word of God. Twelve minor prophets of coming of elijah the volume on those big messages had formerly promised hope and enter and god leads those that, search the testament prophets? Habakkuk: Habakkuk covered a lot of ground in such a short book. You can get answers to your questions about the Faith by listening to our Podcasts like Catholic Answers Live or The Counsel of Trent. Forschungen zum Alten Testament. -

Mary the Mother of Jesus When He Said

What Does Following Jesus Look Like? Rich Nathan July 12-13, 2014 Forever Changed: The Women Who Met Jesus Series Luke 1:26-55 There is a story that comes out of the 1500’s in Scotland. The Protestant Reformation was just beginning in Scotland and the leader of the Reformation there was named John Knox, who was violently anti-Roman Catholic. When John Knox was a young man, he was taken prisoner and forced to row in a French galley ship for almost 2 years. Here is an incident from John Knox’s journal. He writes: Soon after the arrival of the ship [in France] a glorious painted image of Mary was brought in to be kissed and was presented to one of the Scottish men [me] then chained. I gently said, “Trouble me not; such an idol is a curse; and therefore I will not touch it.” The soldiers with two officers, having the chief charge of all such matters said, “You shall handle it” and they violently thrust it in my face and between my hands; who seeing the emergency, took the idol, and advisedly looking about I cast it in the river and said, “Let our Lady now save herself: she is light enough; let her learn to swim!” For much of the last 2000 years the Christian church has swung wildly from one extreme to the other concerning how we are to regard Mary, the Mother of Jesus. On the one hand, we have what some people would call “Mariolatry” – a devotion to Mary bordering on idolatry. -

Illumination the Prophet Nathan Receives a Word from the Lord for King David, Professing the Great Things Which God Commits to Do for the House and Family of David

Illumination The prophet Nathan receives a word from the Lord for King David, professing the great things which God commits to do for the house and family of David. FIRST READING: 2 Samuel 7:1-11, 16 A Reading from the Second book of Samuel. 1Now when the king was settled in his house, and the Lord had given him rest from all his enemies around him, 2the king said to the prophet Nathan, “See now, I am living in a house of cedar, but the ark of God stays in a tent.” 3Nathan said to the king, “Go, do all that you have in mind; for the Lord is with you.” 4But that same night the word of the Lord came to Nathan: 5Go and tell my servant David: Thus says the Lord: Are you the one to build me a house to live in? 6I have not lived in a house since the day I brought up the people of Israel from Egypt to this day, but I have been moving about in a tent and a tabernacle. 7Wherever I have moved about among all the people of Israel, did I ever speak a word with any of the tribal leaders of Israel, whom I commanded to shepherd my people Israel, saying, “Why have you not built me a house of cedar?” 8Now therefore thus you shall say to my servant David: Thus says the Lord of hosts: I took you from the pasture, from following the sheep to be prince over my people Israel; 9and I have been with you wherever you went, and have cut off all your enemies from before you; and I will make for you a great name, like the name of the great ones of the earth. -

Moses Deborah Samuel Gad and Nathan Elijah and Elisha Amos

PROPHECY, PROPHETS Reception and declaration of a word from the Lord through a direct prompting of the Holy Spirit and the human instrument thereof. Old Testament Three key terms are used of the prophet. Ro'eh and hozeh are translated as "seer." The most important term, nabi, is usually translated "prophet." It probably meant "one who is called to speak." Moses History Moses, perhaps Israel's greatest leader, was a prophetic prototype (Acts 3:21-24). He appeared with Elijah in the transfiguration (Matt. 17:1-8). Israel looked for a prophet like Moses (Deut. 34:10). Deborah Prophets also played a role in the conquest and settlement of the Promised Land. The prophetess Deborah predicted victory, pronounced judgment on doubting Barak, and even identified the right time to attack (Judg. 4:6-7,9,14). Samuel Samuel, who led Israel during its transition to monarchy, was a prophet, priest, and judge (1 Sam. 3:20; 7:6,15). He was able to see into the future by vision (3:11-14) and to ask God for thunder and rain (12:18). Samuel led in victory over the Philistines (1 Sam. 7), and God used him to anoint kings. Gad and Nathan Gad and Nathan served as prophets to the king. Elijah and Elisha Elijah and Elisha offered critique and advice for the kings. The prophets did more than predict the future; their messages called Israel to honor God. Their prophecies were not general principles but specific words corresponding to Israel's historical context. Amos, Hosea, Isaiah, Micah Similarly the classical or writing prophets were joined to history. -

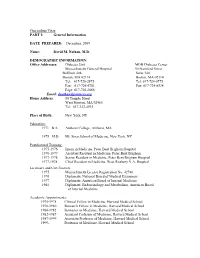

Curriculum Vitae PART I: General Information

Curriculum Vitae PART I: General Information DATE PREPARED: December, 2009 Name: David M. Nathan, M.D. DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION: Office Addresses: Diabetes Unit MGH Diabetes Center Massachusetts General Hospital 50 Staniford Street Bulfinch 408 Suite 340 Boston, MA 02114 Boston, MA 02114 Tel: 617-726-2875 Tel: 617-724-0775 Fax: 617-726-6781 Fax: 617-724-8534 Page: 617-726-2066 Email: [email protected] Home Address: 80 Temple Street West Newton, MA 02465 Tel: 617-332-4935 Place of Birth: New York, NY Education: 1971 B.A. Amherst College, Amherst, MA 1975 M.D. Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY Postdoctoral Training: 1975-1976 Intern in Medicine, Peter Bent Brigham Hospital 1976-1977 Assistant Resident in Medicine, Peter Bent Brigham 1977-1978 Senior Resident in Medicine, Peter Bent Brigham Hospital 1977-1978 Chief Resident in Medicine, West Roxbury V.A. Hospital Licensure and Certification: 1975 Massachusetts License Registration No. 42740 1976 Diplomate, National Board of Medical Examiners 1977 Diplomate, American Board of Internal Medicine 1981 Diplomate, Endocrinology and Metabolism, American Board of Internal Medicine Academic Appointments: 1975-1978 Clinical Fellow in Medicine, Harvard Medical School 1978-1980 Research Fellow in Medicine, Harvard Medical School 1980-1982 Instructor in Medicine, Harvard Medical School 1982-1987 Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School 1987-1999 Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School 1999- Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School Hospital or Affiliated -

When God Disappoints Jonah 4:1-4

When God Disappoints Jonah 4:1-4 Introduction Good morning, my name is Brad and I’m one of the pastors here. Over the past couple months we have been focusing on what it means to have the identity of an Eyewitness to the grace of God. Guiding us along the way has been a sermon series in the book of Jonah titled, “The Pursuit of Those Far From God,” along with Eyewitness Trainings for men and women. One other way we’re driving this home is by capturing short videos of the everyday work of members in our church, the classrooms and cubicles where our people are sent week after week to experience the presence of God and participate in his mission. Let’s watch another one together: [Bill Stayton video]. Thanks, Bill, for giving us a glimpse into your life and ministry, and thanks to Dan Bush for putting these videos together. If anyone else is interested in doing one of these, let me know and we’ll send Dan your way. Today we’re breaking open the final chapter of Jonah with a message titled, “When God Disappoints”. The passage we’ll be looking at is Jonah 4:1-4. Here is today’s main idea: Anger at God reveals a problem at heart. We’ll basically unpack that in two parts: Jonah’s Anger at God - vv. 1-2 and Jonah’s Problem at Heart - vv. 3-4. With that said, if you are able, please stand with me to honor the reading of God’s word. -

52 Was Joseph a Type of the Messiah? Tracing the Typological Identification Between Joseph, David, and Jesus

Was Joseph a Type of the Messiah? Tracing the Typological Identification between Joseph, David, and Jesus James M. Hamilton James M. Hamilton serves as This typological way of reading written up by Moses may have been Associate Professor of Biblical Theology the Bible is indicated too often and influenced by the story of Cain and Abel.3 at The Southern Baptist Theological explicitly in the New Testament itself for us to be in any doubt that The presence of these elements in the Seminary. He previously served as this is the “right” way of reading Joseph story then exercised influence on Assistant Professor of Biblical Studies it—“right” in the only sense that the selection of events included in the criticism can recognize, as the way at Southwestern Baptist Theological 4 5 6 that conforms to the intentionality stories of Moses, Daniel, Esther, and Seminary’s Houston campus and of the book itself and to the conven- Nehemiah.7 Each of these instances could tions it assumes and requires. was the preaching pastor at Baptist be studied in their own right, but in this Naturally, being the indicated and Church of the Redeemer in Houston, obvious way of reading the Bible, essay we will focus on the narrative cor- Texas. Dr. Hamilton has written many and scholars being what they are, respondences between Joseph and David scholarly articles and is the author of typology is a neglected subject, even in theology, and it is neglected before looking to Jesus. My contention in God’s Indwelling Presence: The Ministry elsewhere because it is assumed the first part of this essay is that the story of the Holy Spirit in the Old and New to be bound up with a doctrinaire of Joseph in Genesis 37–50 was a forma- Testaments (B&H, 2006). -

Unto Others an Exploration of Christianity As an Accomplice and Adversary to the Aims of Empire in Barbara Kingsolver's the P

Unto Others An exploration of Christianity as an accomplice and adversary to the aims of empire in Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible. by Anna Paauwe Unto Others An exploration of Christianity as an accomplice and adversary to the aims of empire in Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible. by Anna Paauwe A thesis presented for the B.A. degree With Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Spring 2010 © 22 March 2010, Anna Paauwe. A faithful friend is a sturdy shelter: He that has found one has found a treasure. There is nothing so precious as a faithful friend. (Sirach 6:14) To my best friend, Madelyn Ladner Green. Thank you for everything, I love you. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis cohort director, Cathy Sanok for her inspiration in moments of writers block, my advisor Jennifer Wenzel for her invaluable guidance and expertise, my family without whom this project would not have been possible, and my dedicated editors who helped me polish and perfect this manuscript. Abstract Shedding light on one of the darkest moments in both Congolese and American history, Barbara Kingsolver’s novel, The Poisonwood Bible, explores the relationship between religion and imperialism, missionaries and conquerors. Set on the eve of the Congo’s independence from Belgium, Kingsolver’s novel centers on a 1950’s Georgian family bringing God’s light to the small Congolese village of Kilanga. Following the militant and fanatical minister, Nathan Price, each of the five Price women gradually experiences the consequences of Nathan’s unflinching fundamentalism, realizing him to be ineffective as both a provider and a spiritual leader. -

Double Meaning in the Parable of the Poor Man's Ewe (2 Sam 12:1–4)

Journal of Hebrew Scriptures Volume 13, Article 14 DOI:10.5508/jhs.2013.v13.a14 Double Meaning in the Parable of the Poor Man's Ewe (2 Sam 12:1–4) JOSHUA BERMAN Articles in JHS are being indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, RAMBI, and BiBIL. Their abstracts appear in Religious and Theological Abstracts. The journal is archived by Library and Archives Canada and is accessible for consultation and research at the Electronic Collection site maintained by Library and Archives Canada. ISSN 1203–1542 http://www.jhsonline.org and http://purl.org/jhs DOUBLE MEANING IN THE PARABLE OF THE POOR MAN’S EWE (2 SAM 12:1–4) JOSHUA BERMAN BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY In this article I offer a new solution to an age-old interpretive crux: the meaning of the parable of the poor man’s ewe (2 Sam 12:1–4) in light of the surrounding narrative of the David and Bathsheba account of 2 Sam 11–12. Ever since the Middle Ages commenta- tors to this passage have noted the apparent incongruity between the elements of the parable on the one hand and the elements of the surrounding narrative on the other.1 Although some scholars have suggested readings that attempt a close mapping of equiva- lents between parable and narrative, most opinions have resisted such a close mapping and have opted instead for what I will refer to here as the “conventional approach” to the issue.2 In the first part of this study, I review the merits and demerits of that ap- proach.