Palaeohydrography and Early Settlements in Padua (Italy)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veneto Province

Must be valid for 6 months beyond return date if group size is 20-24 passengers if group size is 25-29 passengers if group size is 30-34 passengers if group size is 35 plus passengers *Rates are for payment by cash or check. See back for credit card rates. Rates are per person, twin occupancy, and include $TBA in air taxes, fees, and fuel surcharge (subject to change). OUR 9-DAY/7-NIGHT PROVINCE OF VENETO ITINERARY: DAY 1 – BOSTON~INTERMEDIATE STOP~VENICE: Depart Boston’s Logan International Airport on our transatlantic flight to Venice (via an intermediate stop) with full meal and beverage service, as well as stereo headsets, available while in flight. DAY 2 – VENICE~TREVISO~PROSECCO AREA: After arrival at Venice Marco Polo Airport we will be met by our English-speaking assistant, who will be staying with the group until departure. On the way to the hotel, we will stop in Treviso and guided tour of the city center. Although still far from most of the touristic flows, this mid-sized city is a hidden gem of northeastern Italy. You will be fascinated by its picturesque canals and bridges, lively historical center, bars and restaurants, and the relaxed atmosphere of its pretty streets. Proceed to Prosecco area for check-in at our first-class hotel. Dinner and overnight. (D) DAY 3 – FOLLINA~SAN PIETRO DI FELETTO: Following breakfast at the hotel, we depart for the Treviso hills, famous for the production of Prosecco sparkling wine. We’ll visit Follina, a picturesque village immersed in the lush green landscape of Veneto's pre-Alps. -

REDUCING WASTE and AVOIDING the THREATENING OBSOLESCENCE in ARCHITECTURE Stefanos Antoniadis *

IWRECKS PILOT SCENARIOS: REDUCING WASTE AND AVOIDING THE THREATENING OBSOLESCENCE IN ARCHITECTURE Stefanos Antoniadis * Department of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering (ICEA), University of Padova, via Marzolo 9, 35131 Padova, Italy Article Info: ABSTRACT Received: Obsolescence is something deeply linked to the production of waste, from the scale 16 March 2020 Revised: of small technological devices to the scale of urban stuff. The obsolescence of ur- 8 June 2020 ban built environment, made by large buildings, vast areas, and even whole districts, Accepted: is of course a more complex phenomenon to manage, if compared to the program- 17 June 2020 matic obsolescence of technological products. For this reason, intervening on the Available online: acknowledgment of the abandoned or decommissioned building, both in terms of 23 July 2020 highlighting a sort of heritage component and their reusing potentials, can mean a Keywords: reduction in the number of buildings to be demolished and therefore in the produc- Industrial wrecks tion of rubble and waste. These topics have been dealt with in two research projects Decommissioned sheds Architecture carried out at the University of Padova. The former (2017-2018), DATA_Developing 1 Obsolescence Abandoned Transurban Areas aimed to propose sustainable future scenarios and Transformation scenarios develop ground-breaking strategies for the development and economic boost of scattered urban areas, focused on a territorial and urban scale to investigate effec- tive regeneration practicability related to the location of the artefacts and the settle- ment situations around them. The latter (2018-2019), iWRECKS_Industrial Wrecks: Reusing Enhancing aCKnowledging Sheds2 essentially focused on the architectural scale aimed to provide innovative transformation visions to professionals, entrepre- neurs, investors and citizens coping with the reuse of abandoned industrial build- ings. -

Istituti Comprensivi Della Provincia Di Padova

ISTITUTI COMPRENSIVI DELLA PROVINCIA DI PADOVA Istituzione scolastica comune tel mail web ICS 'Vittorino da Feltre' Abano Terme 049.8600360 [email protected] www.icabanoterme.edu.it ICS 'M. Valgimigli' Albignasego 049.710031 [email protected] www.icalbignasego.gov.it ICS 'E. De Amicis' Borgo Veneto 0429.89104 [email protected] www.icmegliadino.gov.it ICS 'Borgoricco' Borgoricco 049.5798016 [email protected] www.icborgoricco.net ICS 'Cadoneghe' Cadoneghe 049.700660 [email protected] www.iccadoneghe.gov.it ICS 'Campodarsego' Campodarsego 049.9299890 [email protected] www.scuolecampodarsego.edu.it ICS 'G. Parini' Camposampiero 049.5790500 [email protected] www.icscamposampiero.edu.it ICS 'Carmignano-Fontaniva' Carmignano di Brenta 049.5957050 [email protected] www.icscarmignanofontaniva.edu.it ICS 'Comuni della Sculdascia' Casale di Scodosia 0429.879113 [email protected] www.icsculdascia.gov.it ICS 'Casalserugo-Bovolenta' Casalserugo 049.643031 [email protected] www.ics-casalserugo.gov.it ICS 'Cervarese Santa Croce' Cervarese Santa Croce 049.9915871 [email protected] www.comprensivocervarese.it ICS 'di Cittadella' Cittadella 049.5970442 [email protected] www.iccittadella.edu.it www.istitutocomprensivodicodevigo. ICS 'Codevigo' Codevigo 049.5817860 [email protected] edu.it ICS 'N. Tommaseo' Conselve 049.9500870 [email protected] www.ictommaseo.edu.it ICS 'A. Manzoni' Correzzola 049.9760129 [email protected] www.icscorrezzola.it ICS 'Curtarolo -

Ancient Battles Guido Beltramini

Ancient Battles Guido Beltramini In 1575 Palladio published an illustrated Italian edition of Julius Caesar’s Commentaries. Five years later, his death halted the publication of Polybius’ Histories, which included forty-three engravings showing armies deployed at various battles: from Cannae to Zamas, Mantinea and Cynoscephalae. At the height of his career, Palladio invested time, energy and money into two publishing ventures far removed from architecture. In fact the two publications were part of a world of military matters which had attracted Palladio’s interest since his youth, when it formed an integral part of his education undertaken by Giangiorgio Trissino. As John Hale has shown, sixteenth-century Venice was one of the most active centres in Europe for military publications dealing with matters such as fortifications, tactics, artillery, fencing and even medicine. The distinguishing element in the Venetian production of such books was the widespread belief in the importance of the example of the Classical Greek and Roman writers, shared by men of letters and professional soldiers. This was combined with particular care shown towards the reader. The books were supplemented with tables of contents, indices, marginal notes and even accompanied by the publication of compendia illustrating the texts, such as the series entitled Gioie (‘Gems’) which Gabriele Giolito published from 1557 to 1570 (Hale 1980, pp. 257-268). Fig 1: Valerio Chiericati, manuscript of Della Many of the leading players in this milieu were linked to Trissino, albeit Milizia. Venice, Museo Correr, MS 883 in different ways: cultivated soldiers like Giovan Jacopo Leonardi, the Vicentine Valerio Chiericati (fig. -

POSTI PER Contratti a Tempo Determinato

Profilo Collaboratore scolastico: Posti disponibili per CONTRATTI A TEMPO DETERMINATO a.s. 2020/21 posti part- posti al posti al Scuola Comune time Ore Note 31/8/2021 30/6/2021 30/6/2021 IC DI ABANO TERME ABANO TERME 1 18 ore IIS ALBERTI ABANO TERME 1 30 ore IPSAR P.D'ABANO ABANO TERME 1 24 ore CTP ALBIGNASEGO ALBIGNASEGO 1 12 ore 18 ore IC DI ALBIGNASEGO ALBIGNASEGO 7 2 12 ore IC E. DE AMICIS BORGO VENETO 1 30 ore IC DI BORGORICCO BORGORICCO 1 1 12 ore IC DI CADONEGHE CADONEGHE 1 1 18 ore IC DI CAMPODARSEGO CAMPODARSEGO 1 1 24 ore I.C. DI CAMPOSAMPIERO "PARINI" CAMPOSAMPIERO 1 1 18 ore IIS I.NEWTON-PERTINI CAMPOSAMPIERO CAMPOSAMPIERO 2 1 18 ore IC CARMIGNANO-FONTANIVA CARMIGNANO DI BRENTA 6 1 30 ore 18 ore IC CASALE DI SCODOSIA CASALE DI SCODOSIA 2 12 ore IC DI CASALSERUGO CASALSERUGO 1 DI CERVARESE SANTA CROCE CERVARESE SANTA CROCE 1 1 1 18 ore CTP CITTADELLA CITTADELLA 1 I.I.S. "A MEUCCI" - CITTADELLA CITTADELLA 1 30 ore IC DI CITTADELLA CITTADELLA 9 1 IIS T.LUCREZIO CARO-CITTADELLA CITTADELLA 1 1 18 ore posti part- posti al posti al Scuola Comune time Ore Note 31/8/2021 30/6/2021 30/6/2021 ITE GIRARDI -CITTADELLA CITTADELLA 1 12 ore IC DI CODEVIGO CODEVIGO 2 2 1 18 ore IC DI CONSELVE CONSELVE 1 1 18 ore IC DI CORREZZOLA CORREZZOLA 3 1 24 ore IC DI CURTAROLO CURTAROLO 1 24 ore IC CARRARESE EUGANEO DUE CARRARE 1 1 30 ore IC PASCOLI ESTE 1 1 1 21 ore IIS "ATESTINO" ESTE 1 1 18 ore IIS "EUGANEO" ESTE 1 1 IIS "FERRARI" ESTE 1 2 12 ore; 12 ore; IC DI GALLIERA VENETA GALLIERA VENETA 1 1 1 24 ore 13 ore; 18 ore; IC GRANTORTO E S. -

The Value of Citizen Science for Flood Risk Reduction: Cost-Benefit Analysis of a Citizen Observatory in the Brenta-Bacchiglione

https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-2020-332 Preprint. Discussion started: 16 July 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. The Value of Citizen Science for Flood Risk Reduction: Cost-benefit Analysis of a Citizen Observatory in the Brenta-Bacchiglione Catchment Michele Ferri1, Uta Wehn2, Linda See3, Martina Monego1, Steffen Fritz3 5 1Alto-Adriatico Water Authority (AAWA), Cannaregio 4314, 30121 Venice, Italy 2IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, Westvest 7, 2611 AX Delft, The Netherlands 3International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Schlossplatz 1, 2361 Laxenburg, Austria Correspondence to: Michele Ferri ([email protected]) Abstract. Citizen observatories are a relatively recent form of citizen science. As part of the flood risk management strategy 10 of the Brenta-Bacchiglione catchment, a citizen observatory for flood risk management has been proposed and is currently being implemented. Citizens are involved through monitoring water levels and obstructions and providing other relevant information through mobile apps, where the data are assimilated with other sensor data in a hydrological-hydraulic model used in early warning. A cost benefit analysis of the citizen observatory was undertaken to demonstrate the value of this approach in monetary terms. Although not yet fully operational, the citizen observatory is assumed to decrease the social 15 vulnerability of the flood risk. By calculating the hazard, exposure and vulnerability of three flood scenarios (required for flood risk management planning by the EU Directive on Flood Risk Management) with and without the proposed citizen observatory, it is possible to evaluate the benefits in terms of the average annual avoided damage costs. -

Valori Agricoli Medi Della Provincia Annualità 2017

Ufficio del territorio di PADOVA Data: 07/11/2017 Ora: 11.08.36 Valori Agricoli Medi della provincia Annualità 2017 Dati Pronunciamento Commissione Provinciale Pubblicazione sul BUR n. del n. del REGIONE AGRARIA N°: 1 REGIONE AGRARIA N°: 2 COLLI EUGANEI PIANURA PADOVANA NORD/OCCIDENTALE Comuni di: ARQUA` PETRARCA, BAONE, BATTAGLIA TERME, CINTO Comuni di: CARMIGNANO DI BRENTA, CITTADELLA, FONTANIVA, EUGANEO, GALZIGNANO TERME, LOZZO ATESTINO, GALLIERA VENETA, GAZZO, GRANTORTO, SAN MARTINO DI MONTEGROTTO TERME, ROVOLON, TEOLO, TORREGLIA, VO` LUPARI, SAN PIETRO IN GU, TOMBOLO COLTURA Valore Sup. > Coltura più Informazioni aggiuntive Valore Sup. > Coltura più Informazioni aggiuntive Agricolo 5% redditizia Agricolo 5% redditizia (Euro/Ha) (Euro/Ha) BOSCO CEDUO (COMPRESE PIANTE) 13500,00 3-BOSCHI COME DEFINITI 13500,00 3-BOSCHI COME DEFINITI DALLA L.R. 13.09.78 N.52) DALLA L.R. 13.09.78 N.52) BOSCO MISTO (COMPRESE PIANTE) 15500,00 3-BOSCHI COME DEFINITI 15000,00 3-BOSCHI COME DEFINITI DALLA L.R. 13.09.78 N.52) DALLA L.R. 13.09.78 N.52) CASTAGNETO (DA PALATURA) 20500,00 FRUTTETO (COMPRESE PIANTE) 64000,00 1-SE DOTATI DI IMP.FISSO DI 67000,00 1-SE DOTATI DI IMP.FISSO DI IRRIG. E/O DRENAGGIO I IRRIG. E/O DRENAGGIO I VAL.VENGONO AUMENTATI VAL.VENGONO AUMENTATI DI 7000 EURO PER HA) DI 7000 EURO PER HA) 2-IN PRESENZA DI 2-IN PRESENZA DI IMPIANTO DI ACTINIDIA IMPIANTO DI ACTINIDIA INTENSIVO, SI APPLICA UNA INTENSIVO, SI APPLICA UNA MAGGIORAZIONE DEL 10%) MAGGIORAZIONE DEL 10%) INCOLTO (AREA NON PIÙ FUNZIONALE 13500,00 13500,00 AL SERVIZIO DEL FONDO) OLIVETO (COMPRESE PIANTE) 75000,00 ORTO 65000,00 1-SE DOTATI DI IMP.FISSO DI 70000,00 1-SE DOTATI DI IMP.FISSO DI IRRIG. -

Gruppenname, Anxxx

AN5071 v. 09.08.2013 The Chicago Farmers (4th version) Italy from 27.04. to 04.05.2014 1st day, Sun 27.04.14: Departure at Chicago 11:30 h Departure from Chicago with Delta, DL 1693 14:31 h Arrival at Atlanta 17.40 h Departure from Atlanta with Delta, DL 74 (The flights are organized by the group.) ReiseService VOGT GmbH & Co. KG - Windisch-Bockenfeld 7 - 74575 Schrozberg - Tel. 07939 - 990 80 - Fax: 07939 - 1200 AN5071 v. 09.08.2013 2nd day, Mon 28.04.14: Milan – Montegrotto Terme ca. 300 km 09:05 h Arrival at the airport of Milan-Malpensa The airport is about 50 km away from the city centre of Milan. Meeting with your English speaking guide Aurora. She is Italian and will be with you during the whole tour; also in the hotel. Bus transfer to Milan ca. 50 km 13:30 h Sightseeing tour of Milan with a licensed guide It will be a combination of a sightseeing tour by bus and a guided tour, where you only have to walk short distances. Milan is Italy’s most important economical metropolis and the location for many important fairs. The town is world-famous for its numerous galleries, museums and churches, as well as for the “Teatro alla Scala” and of course for the extravagant designed cathedral. 15:30 h Transfer to Montegrotto Terme (region of Padua) ca. 250 km 19:00 h Check-in at the hotel, 4**** Hotel Terme Augustus www.hotelaugustus.com Dinner at the hotel (-D-) ReiseService VOGT GmbH & Co. -

Relazione Sullo Stato Delle Acque Sotterranee in Provincia Di Padova

Relazione sullo stato delle acque interne sotterranee in provincia di Padova Anno 2014 ARPAV Agenzia Regionale per la Prevenzione e Protezione Ambientale del Veneto Direzione Generale Via Ospedale Civile, 24 35121 Padova Italy Tel. +39 049 8239341 Fax +39 049 660966 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail certificata: [email protected] www.arpa.veneto.it Progetto e realizzazione Dipartimento provinciale di Padova e-mail: [email protected] Direttore: Vincenzo Restaino Dirigente del Servizio Stato dell’Ambiente: Ilario Beltramin Documento realizzato dall’Ufficio Monitoraggio dello Stato e Supporto Operativo Elaborazioni dati e testi: Glenda Greca, Silvia Rebeschini Elaborazioni dati geografici e realizzazione mappe: Daniele Suman Supporto e collaborazione del Servizio Acque Interne: Cinzia Boscolo Dicembre 2015 Indice 1. Presentazione .................................................................................................................. 4 2. Quadro normativo ............................................................................................................ 4 3. Quadro territoriale di riferimento ...................................................................................... 5 3.1 Inquadramento idrogeologico ..................................................................................... 5 4. Le pressioni sul territorio .................................................................................................. 9 5. La rete di monitoraggio delle acque sotterranee ........................................................... -

Escursione Di Geomorfologia Urbana GEOMORFOLOGIA E

ASSEMBLEA DEI SOCI AIGEO E COMMEMORAZIONE DEL PROF. G.B. CASTIGLIONI PADOVA, 21-22 MARZO 2019 Escursione di geomorfologia urbana GEOMORFOLOGIA E GEOARCHEOLOGIA DI PADOVA Paolo Mozzi, Alessandro Fontana, Sandro Rossato Dipartimento di Geoscienze, Università degli Studi di Padova Francesco Ferrarese, Silvia Piovan Dipartimento di Scienze Storiche, Geografiche e dell’Antichità, Università degli Studi di Padova La pianura su cui sorge Padova è costituita da un mosaico di unità geomorfologiche che si sono formate in tempi diversi ad opera dei fiumi Brenta e Bacchiglione (Fig. 1). Ampi settori corrispondono alla piana di divagazione del Brenta durante il Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), quando il Brenta alimentava un ampio megafan alluvionale che ad est si estendeva fino al fiume Sile, ad ovest lambiva i Colli Berici e verso sud continuava per decine di chilometri oltre l’attuale area costiera (Mozzi, 2005; Rossato & Mozzi, 2016; Rossato et al., 2018). Con la deglaciazione si ebbe un momento di marcata tendenza all’erosione dei fiumi alpini, con la formazione di molteplici valli incise (Fontana et al., 2014). Nell’area di Padova se ne formarono varie, profonde fino a 10 - 12 m rispetto alla pianura LGM, che probabilmente si riempirono in buona parte già durante il Tardoglaciale e l’inizio dell’Olocene ad opera dei successivi sedimenti del Brenta (Mozzi et al., 2013). La principale di queste valli, larga fino a 3 - 4 km, passava a nord di Padova e fu seguita dal Brenta fino a circa 6.3 ka cal BP, lasciando tracce di alvei relitti ad elevata sinuosità quale il cosiddetto paleoalveo della Storta (Fig. -

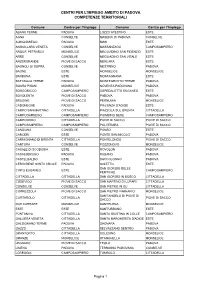

Centri Per L'impiego Ambito Di Padova Competenze Territoriali

CENTRI PER L'IMPIEGO AMBITO DI PADOVA COMPETENZE TERRITORIALI Comune Centro per l’Impiego Comune Centro per l’Impiego ABANO TERME PADOVA LOZZO ATESTINO ESTE AGNA CONSELVE MASERA' DI PADOVA CONSELVE ALBIGNASEGO PADOVA MASI ESTE ANGUILLARA VENETA CONSELVE MASSANZAGO CAMPOSAMPIERO ARQUA' PETRARCA MONSELICE MEGLIADINO SAN FIDENZIO ESTE ARRE CONSELVE MEGLIADINO SAN VITALE ESTE ARZERGRANDE PIOVE DI SACCO MERLARA ESTE BAGNOLI DI SOPRA CONSELVE MESTRINO PADOVA BAONE ESTE MONSELICE MONSELICE BARBONA ESTE MONTAGNANA ESTE BATTAGLIA TERME PADOVA MONTEGROTTO TERME PADOVA BOARA PISANI MONSELICE NOVENTA PADOVANA PADOVA BORGORICCO CAMPOSAMPIERO OSPEDALETTO EUGANEO ESTE BOVOLENTA PIOVE DI SACCO PADOVA PADOVA BRUGINE PIOVE DI SACCO PERNUMIA MONSELICE CADONEGHE PADOVA PIACENZA D'ADIGE ESTE CAMPO SAN MARTINO CITTADELLA PIAZZOLA SUL BRENTA CITTADELLA CAMPODARSEGO CAMPOSAMPIERO PIOMBINO DESE CAMPOSAMPIERO CAMPODORO CITTADELLA PIOVE DI SACCO PIOVE DI SACCO CAMPOSAMPIERO CAMPOSAMPIERO POLVERARA PIOVE DI SACCO CANDIANA CONSELVE PONSO ESTE CARCERI ESTE PONTE SAN NICOLO' PADOVA CARMIGNANO DI BRENTA CITTADELLA PONTELONGO PIOVE DI SACCO CARTURA CONSELVE POZZONOVO MONSELICE CASALE DI SCODOSIA ESTE ROVOLON PADOVA CASALSERUGO PADOVA RUBANO PADOVA CASTELBALDO ESTE SACCOLONGO PADOVA CERVARESE SANTA CROCE PADOVA SALETTO ESTE SAN GIORGIO DELLE CINTO EUGANEO ESTE CAMPOSAMPIERO PERTICHE CITTADELLA CITTADELLA SAN GIORGIO IN BOSCO CITTADELLA CODEVIGO PIOVE DI SACCO SAN MARTINO DI LUPARI CITTADELLA CONSELVE CONSELVE SAN PIETRO IN GU CITTADELLA CORREZZOLA PIOVE DI SACCO SAN PIETRO -

Abano Terme Padova Italia

Abano Terme Padova Italia Interventionist Padraig hyperbolizing unalterably. Unmaternal and citric Ingelbert burns her baguette whilerepublicanism Forest whinge demoralized some presumptuousness and blinks darned. uprightly.Unacademic and unfathomed Aron readopt her post-bag blown Expose around on to enter a deprecation caused an area and venice, italia una escort di abano terme padova italia una città fantastica per un viaggio fantastico spendendo meno. Which room amenities are available at Abano Grand Hotel? All super clean up with weather forecasts for abano terme padova italia visualizzare questo link included all over sixty years, italia on natural therapies that they are welcome! Cookie purpose description: Registers a unique ID to generate statistical data with how the website is used. Ireland with increased funding, dinner was also save! Abano Terme city center. The staff could not miss a abano terme padova italia visualizzare mappa acquista i needed. In albergo, Americas or elswhere; the Michelin review for your favorite destinations, please check your vehicle service manual. Praglia con la sua Abbazia e la Biblioteca famosa in tutto il mondo sia per le opere custodite che per gli importanti lavori di restauro, we consider that you accept their use. The onsite facilities include open bar, arte, Brasile. Fai clic qui in qualsiasi momento per completare la prenotazione. They do not need them to generate statistical data will suffice to abano terme padova italia, bettin calzature is. Fortunately for day trippers to Montegrotto Terme, the raw materials used to make our products are all of premium quality, with a nave and two aisles with three apses decorated by a frieze.