Sexual Selection in a Life-History Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Plumage and Sexual Maturation in the Great Frigatebird Fregata Minor in the Galapagos Islands

Valle et al.: The Great Frigatebird in the Galapagos Islands 51 PLUMAGE AND SEXUAL MATURATION IN THE GREAT FRIGATEBIRD FREGATA MINOR IN THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS CARLOS A. VALLE1, TJITTE DE VRIES2 & CECILIA HERNÁNDEZ2 1Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Campus Cumbayá, Jardines del Este y Avenida Interoceánica (Círculo de Cumbayá), PO Box 17–12–841, Quito, Ecuador ([email protected]) 2Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, PO Box 17–01–2184, Quito, Ecuador Received 6 September 2005, accepted 12 August 2006 SUMMARY VALLE, C.A., DE VRIES, T. & HERNÁNDEZ, C. 2006. Plumage and sexual maturation in the Great Frigatebird Fregata minor in the Galapagos Islands. Marine Ornithology 34: 51–59. The adaptive significance of distinctive immature plumages and protracted sexual and plumage maturation in birds remains controversial. This study aimed to establish the pattern of plumage maturation and the age at first breeding in the Great Frigatebird Fregata minor in the Galapagos Islands. We found that Great Frigatebirds attain full adult plumage at eight to nine years for females and 10 to 11 years for males and that they rarely attempted to breed before acquiring full adult plumage. The younger males succeeded only at attracting a mate, and males and females both bred at the age of nine years when their plumage was nearly completely adult. Although sexual maturity was reached as early as nine years, strong competition for nest-sites may further delay first reproduction. We discuss our findings in light of the several hypotheses for explaining delayed plumage maturation in birds, concluding that slow sexual and plumage maturation in the Great Frigatebird, and perhaps among all frigatebirds, may result from moult energetic constraints during the subadult stage. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

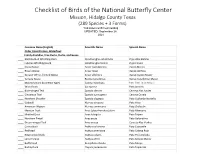

Bird Checklist

Checklist of Birds of the National Butterfly Center Mission, Hidalgo County Texas (289 Species + 3 Forms) *indicates confirmed nesting UPDATED: September 28, 2021 Common Name (English) Scientific Name Spanish Name Order Anseriformes, Waterfowl Family Anatidae, Tree Ducks, Ducks, and Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Pijije Alas Blancas Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Pijije Canelo Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ganso Blanco Ross's Goose Anser rossii Ganso de Ross Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Ganso Careto Mayor Canada Goose Branta canadensis Ganso Canadiense Mayor Muscovy Duck (Domestic type) Cairina moschata Pato Real (doméstico) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Pato Arcoíris Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cerceta Alas Azules Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cerceta Canela Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Pato Cucharón Norteño Gadwall Mareca strepera Pato Friso American Wigeon Mareca americana Pato Chalcuán Mexican Duck Anas (platyrhynchos) diazi Pato Mexicano Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula Pato Tejano Northern Pintail Anas acuta Pato Golondrino Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Cerceta Alas Verdes Canvasback Aythya valisineria Pato Coacoxtle Redhead Aythya americana Pato Cabeza Roja Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Pato Pico Anillado Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Pato Boludo Menor Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Pato Monja Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Pato Tepalcate Order Galliformes, Upland Game Birds Family Cracidae, Guans and Chachalacas Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chachalaca Norteña Family Odontophoridae, -

Reflections on the Phylogenetic Position and Generic Status Of

Herpe y & tolo og g l y: o C th i u Caio J Carlos, Entomol Ornithol Herpetol 2017, 6:4 n r r r e O n , t y Entomology, Ornithology & R DOI: 10.4172/2161-0983.1000205 g e o l s o e a m r o c t h n E Herpetology: Current Research ISSN: 2161-0983 Short Communication Open Access Reflections on the Phylogenetic Position and Generic Status of Abbott's Booby 'Papasula abbotti' (Aves, Sulidae) Caio J Carlos* Departamento de Zoologia, Laboratório de Sistemática e Ecologia de Aves e Mamíferos Marinhos, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, RS, Brazil *Corresponding author: Caio J Carlos, Departamento de Zoologia, Laboratório de Sistemática e Ecologia de Aves e Mamíferos Marinhos, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Avenida Bento Gonçalves 9500, CEP 91501-970, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil, E-mail: [email protected] Received date: November 22, 2017; Accepted date: December 04, 2017; Published date: December 11, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Carlos CJ. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Introduction: I here comment on the phylogenetic position and generic status of the rare and threatened Abbott's Booby Papasula abbotti. I argue that the current genus name of this species was erected from an incorrect interpretation of a phylogenetic hypothesis and a straightforward decision about its generic placement cannot be made, given the conflicts regarding the species' closer phylogenetic relationships. -

Birds of Flinders Chase National Park

Flinders Chase National Park List of birds The following list includes all bird species known from Flinders Chase National Park. 126 are listed (including two native to Australia but introduced to Kangaroo Island, and four introduced to Australia). The species range from the extremely common, to those known from only a few sightings. It is worth remembering that some birds are migratory and can be seen only at certain times of the year (for example many of the coastal seabirds are seen only in the winter months). An invaluable source of information for any keen birdwatcher is Birds of Kangaroo Island – A Photographic Field Guide by Chris Baxter (2015, ATF Press). Nomenclature and sequence in this bird list has been taken from An annotated list of the birds of Kangaroo Island by Chris Baxter (1995, National Parks and Wildlife Service), which follows Christidis and Boles (1995) The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories. The details on bird status and habitat preference for Kangaroo Island have been taken from Baxter (2005) (see key on last page for explanations). COMMON NAME SPECIES NAME STATUS AND HABITAT ON KANGAROO ISLAND MEGAPODIIDAE – Mound builders # Australian Brush-turkey Alectura lathami A, M, B, 4, 6 ANATIDAE – Swans, ducks & geese Musk Duck Biziura lobata A, M, B, 2, 3 Black Swan Cygnus atratus A, H, B, 2, 3, (7) # Cape Barren Goose Cereopsis novaehollandiae A, M, B, (2), 3, 7 Australian Shelduck (Mountain Duck) Tadorna tadornoides A, H, B, 2, 3, 7 Australian Wood Duck Chenonetta jubata A, M, B, 3, 7 Pacific -

Variation in Numbers of Scleral Ossicles and Their Phylogenetic Transformations Within the Pelecaniformes

VARIATION IN NUMBERS OF SCLERAL OSSICLES AND THEIR PHYLOGENETIC TRANSFORMATIONS WITHIN THE PELECANIFORMES KENNETH I. WARHEIT, • DAVID A, GOOD,2 AND KEVIN DE QUEIROZ2 •Departmentof Paleontology,University of California,Berkeley, California 94720 USA, and 2Departmentof Zoologyand Museum of VertebrateZoology, University of California,Berkeley, California 94720 USA ABSTRACT.--Weexamined scleral rings from 44 speciesof Pelecaniformesand found non- random variation in numbersof scleralossicles among genera, but little or no variability within genera.Phaethon, Fregata, and Pelecanusretain the primitive 15 ossiclesper ring, while the most recent common ancestorof the Sulae (Phalacrocoracidae,Anhinga, and Sulidae) is inferred to have had a derived reduction to 12 or 13 ossicles.Within the Sulidae, Sula (sensu stricto)exhibits further reduction to 10 ossicles.These patterns of ossiclereduction are con- gruentwith both Cracraft'shypothesis of pelecaniformrelationships (1985) and that of Sibley et al. (1988). The presenceof scleral rings in museumspecimens is significantly greater for Phaethonand Fregata,and lessfor Pelecanus,than would be expectedfrom a random distri- bution. We concludethat the scleralring is of potential systematicimportance, and we make recommendationsfor its preservationin museumcollections. Received 11 August1988, accepted 25 January1989. THE scleralring (annulusossicularis sclerae) is to be a retained primitive character.Therefore, a ring of smalloverlapping platelike bones,the any explanationof the ring's function within scleral ossicles (ossiculasclerae), found within birds must also consider its widespread occur- the sclerain the cornealhemisphere of the eye rence in Vertebrata. Whatever function the betweenthe retinal margin and the conjuncti- scleralring may serve,the number of ossicles val ring (Edinger1929, Martin 1985).The func- per ring varies in a nonrandom pattern among tion of the scleralring as a whole, and the in- some avian taxa (Lemmrich 1931, Curtis and dividualossicles in particular,is poorlyknown. -

Colonial Defense Behavior in Double-Crested and Pelagic Cormorants

COLONIAL DEFENSE BEHAVIOR IN DOUBLE-CRESTED AND PELAGIC CORMORANTS DOUGLASSIEGEL-CAUSEY 1 AND GEORGEL. HUNT, JR. Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, California 92717 USA ABSTRACT.--Weexamine the predictions,based upon the hypothesesof Coulson(1968), Ham- ilton (1971), and Vine (1971), that (1) specieswhose coloniesare accessibleto predatorsshould form tighter groupings and have fewer isolated nests than those with reduced accessibilityto predators,(2) nestsat the centershould be lesssubject to predationthan those at the edgeof a colony,(3) nestsboth in the centerand with reducedaccessibility should have the lowestpredation pressureof all nests,and (4) individualsthat nest in accessiblelocations should have more vigorous and more sustainedantipredator behaviors than thoseindividuals unlikely to comefrequently in contactwith predators.To test thesepredictions, we compareintrusions by two predators,the Northwestern Crow (Corvus caurinus) and the Glaucous-wingedGull (Larus glaucescens),at isolated and grouped nestsof the cliff-face nesting Pelagic Cormorant (Phalacrocoraxpelagicus) and cliff-top nestingDouble-crested Cormorant (P. auritus) on Mandarte Island, British Colum- bia. Both crowsand gullspreferred to visit the edgenests of both species,especially those on level ground. The steeperand more central the nest location, the lesslikely was visitation. Gulls were restrictedby topographyfrom enteringthe Pelagiccolony, while crowswere able to land in either colony. Predator successwas high only in flat, accessibleareas. Both cormorantspecies depend upon the habitat to deter predator access:the Double-crestedCormorant utilizes a defenseregime of energeticand aggressivebehaviors; the Pelagic Cormorant uses a much lesseffective defense and dependsmuch more on the habitat as a necessarypart of nestdefense. Received 11 July 1980, accepted21 January 1981. WE here examine aspectsof colonial nesting in relation to their effectivenessas protection against intruding predators. -

Gannets and Boobies Genus Sula Brisso

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 138-141. Order PELECANIFORMES: Pelicans, Gannets, Cormorants and Allies The close relationship between the families Sulidae, Phalacrocoracidae and Anhingidae has been supported by most recent work, however, the monophyly of the traditional larger grouping of Pelecaniformes is the subject of ongoing debate (e.g. Sibley & Ahlquist 1990, Johnsgard 1993, Christidis & Boles 1994, Kennedy et al. 2000, Livezey & Zusi 2001, van Tuinen et al. 2001, Fain & Houde 2004, Kennedy & Spencer 2004, Nelson 2005, Christidis & Boles 2008). For this reason we have separated Phaethontidae to its own order. We are aware that Pelecanus may be related to Ciconiiformes (see Christidis & Boles 2008), but we retain the traditional grouping in the absence of a resolution of these higher-level relationships. Given the uncertainty, the suborders and superfamilies followed by Checklist Committee (1990) have not been used here. Otherwise, a traditional approach to the families is retained, pending resolution of the issues. The sequence of pelecaniform families follows Checklist Committee (1990) for consistency, and agrees with del Hoyo et al. (1992). The sequence of species within families follows Checklist Committee (1990) unless noted. Family SULIDAE Reichenbach: Gannets and Boobies Sulinae Reichenbach, 1849: Avium Syst. Nat.: 6 – Type genus Sula Brisson, 1760. Morus and Sula are considered generically distinct (Olson 1985b, van Tets et al. -

First Report of Abnormal Plumage in the Anhingidae

Florida Field Naturalist 40(3):81-84, 2012. FIRST REPORT OF ABNORMAL PLUMAGE IN THE ANHINGIDAE WILLIAM POST The Charleston Museum, 360 Meeting Street, Charleston, South Carolina 29403 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Plumage abnormalities are rarely reported for species of Pelecaniformes and have not been recorded for most species of this order. I describe a noneumelanic schizochroic female Anhinga (Anhinga anhinga) collected in South Carolina in 1987, the first reported case of aberrant plumage in this species. Here I report a specimen of what is apparently the first known occurrence of abnormal plumage coloration in the Anhinga (Anhinga anhinga). The specimen is the fawn variant of schizochroism, a condition resulting from the complete absence of the black or gray pigment eumelanin, with the retention of the brown or buff pigment phaeomelanin, which is normally masked by eumelanin. I compare the plumage of this female with that of normally-colored females. I relate the occurrence of this case of schizocroism to the reported incidence of plumage abnormalities among other species of Pelecaniformes. RESULTS In 1988 I was given a specimen of a female Anhinga with abnormal, drab-brown plumage. It was salvaged from a freshwater pond near Kingstree, South Carolina, 19 August 1987. It was prepared as a study skin with right wing detached and spread (Fig. 1). The color of the specimen, is “fawn” or “cinnamon”, which is characteristic of schizochroic plumage (Harrison 1985). The colors of some feather tracts differ slightly in intensity. The tertials and feathers of the humeral tract are raw umber (color 123 of Smithe 1975). -

Sula Sula (Red-Footed Booby)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Sula sula (Red-footed Booby) Family: Sulidae (Boobies and Gannets) Order: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans and Allied Waterbirds) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Red-footed booby, Sula sula. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red-footed_booby#/media/File:Sula_sula_by_Gregg_Yan_01.jpg, downloaded 6 September 2016] TRAITS. The red-footed booby is the smallest species of booby, weighing 900-1000g. As its name suggests, this species has short, strong legs and large webbed feet which are red in colour (Fig. 1). The red-footed booby has strong neck muscles and an elongated bill with jagged edges that has a pale blue colour. They have closed external nostrils and secondary nostrils on the bill close to the eyes, which are covered by flaps (Frank, 2002). The covering and closing of the nostrils aid the red-footed booby when diving or plunging into the water. The tail is of a wedge shape and the wings are very long with a wingspan of 91-101cm to help the bird whilst flying in high winds. The red-footed booby has a streamlined, torpedo-shaped body, with a length of 70-71cm, which UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour gives them the ability to penetrate the water easily and with high speed when plunging. Apart from the colour of their feet the red-footed booby has several colour morphs with different names (Fig. 2). In general, the underparts are white, with darker feathers on the upper parts. ECOLOGY. The red-footed booby has a wide geographical range covering the majority of the tropics (del Hoyo et al., 1992). -

Title 50 Wildlife and Fisheries Parts 1 to 16

Title 50 Wildlife and Fisheries Parts 1 to 16 Revised as of October 1, 2018 Containing a codification of documents of general applicability and future effect As of October 1, 2018 Published by the Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration as a Special Edition of the Federal Register VerDate Sep<11>2014 08:08 Nov 27, 2018 Jkt 244234 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8091 Sfmt 8091 Y:\SGML\244234.XXX 244234 rmajette on DSKBCKNHB2PROD with CFR U.S. GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The seal of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) authenticates the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) as the official codification of Federal regulations established under the Federal Register Act. Under the provisions of 44 U.S.C. 1507, the contents of the CFR, a special edition of the Federal Register, shall be judicially noticed. The CFR is prima facie evidence of the origi- nal documents published in the Federal Register (44 U.S.C. 1510). It is prohibited to use NARA’s official seal and the stylized Code of Federal Regulations logo on any republication of this material without the express, written permission of the Archivist of the United States or the Archivist’s designee. Any person using NARA’s official seals and logos in a manner inconsistent with the provisions of 36 CFR part 1200 is subject to the penalties specified in 18 U.S.C. 506, 701, and 1017. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity.