Franco Corelli and a Revolution in Singing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 CRONOLOGÍA LICEÍSTA Se Incluye Un Listado Con Las

CRONOLOGÍA LICEÍSTA Se incluye un listado con las representaciones de Aida, de Giuseppe Verdi, en la historia del Gran Teatre del Liceu. Estreno absoluto: Ópera del Cairo, 24 de diciembre de 1871. Estreno en Barcelona: Teatro Principal, 16 abril 1876. Estreno en el Gran Teatre del Liceu: 25 febrero 1877 Última representación en el Gran Teatre del Liceu: 30 julio 2012 Número total de representaciones: 454 TEMPORADA 1876-1877 Número de representaciones: 21 Número histórico: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. Fechas: 25 febrero / 3, 4, 7, 10, 15, 18, 19, 22, 25 marzo / 1, 2, 5, 10, 13, 18, 22, 27 abril / 2, 10, 15 mayo 1877. Il re: Pietro Milesi Amneris: Rosa Vercolini-Tay Aida: Carolina de Cepeda (febrero, marzo) Teresina Singer (abril, mayo) Radamès: Francesco Tamagno Ramfis: Francesc Uetam (febrero y 3, 4, 7, 10, 15 marzo) Agustí Rodas (a partir del 18 de marzo) Amonasro: Jules Roudil Un messaggiero: Argimiro Bertocchi Director: Eusebi Dalmau TEMPORADA 1877-1878 Número de representaciones: 15 Número histórico: 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36. Fechas: 29 diciembre 1877 / 1, 3, 6, 10, 13, 23, 25, 27, 31 enero / 2, 20, 24 febrero / 6, 25 marzo 1878. Il re: Raffaele D’Ottavi Amneris: Rosa Vercolini-Tay Aida: Adele Bianchi-Montaldo Radamès: Carlo Bulterini Ramfis: Antoine Vidal Amonasro: Jules Roudil Un messaggiero: Antoni Majjà Director: Eusebi Dalmau 1 7-IV-1878 Cancelación de ”Aida” por indisposición de Carlo Bulterini. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

Bellini's Norma

Bellini’s Norma - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore There are around 130 recordings of Norma in the catalogue of which only ten were made in the studio. The penultimate version of those was made as long as thirty-five years ago, then, after a long gap, Cecilia Bartoli made a new recording between 2011 and 2013 which is really hors concours for reasons which I elaborate in my review below. The comparative scarcity of studio accounts is partially explained by the difficulty of casting the eponymous role, which epitomises bel canto style yet also lends itself to verismo interpretation, requiring a vocalist of supreme ability and versatility. Its challenges have thus been essayed by the greatest sopranos in history, beginning with Giuditta Pasta, who created the role of Norma in 1831. Subsequent famous exponents include Maria Malibran, Jenny Lind and Lilli Lehmann in the nineteenth century, through to Claudia Muzio, Rosa Ponselle and Gina Cigna in the first part of the twentieth. Maria Callas, then Joan Sutherland, dominated the role post-war; both performed it frequently and each made two bench-mark studio recordings. Callas in particular is to this day identified with Norma alongside Tosca; she performed it on stage over eighty times and her interpretation casts a long shadow over. Artists since, such as Gencer, Caballé, Scotto, Sills, and, more recently, Sondra Radvanovsky have had success with it, but none has really challenged the supremacy of Callas and Sutherland. Now that the age of expensive studio opera recordings is largely over in favour of recording live or concert performances, and given that there seemed to be little commercial or artistic rationale for producing another recording to challenge those already in the catalogue, the appearance of the new Bartoli recording was a surprise, but it sought to justify its existence via the claim that it authentically reinstates the integrity of Bellini’s original concept in matters such as voice categories, ornamentation and instrumentation. -

Staged Treasures

Italian opera. Staged treasures. Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gioacchino Rossini © HNH International Ltd CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS FORMAT UPC Naxos Itxaro Mentxaka, Sondra Radvanovsky, Silvia Vázquez, Soprano / 2.110270 Arturo Chacon-Cruz, Plácido Domingo, Tenor / Roberto Accurso, DVD ALFANO, Franco Carmelo Corrado Caruso, Rodney Gilfry, Baritone / Juan Jose 7 47313 52705 2 Cyrano de Bergerac (1875–1954) Navarro Bass-baritone / Javier Franco, Nahuel di Pierro, Miguel Sola, Bass / Valencia Regional Government Choir / NBD0005 Valencian Community Orchestra / Patrick Fournillier Blu-ray 7 30099 00056 7 Silvia Dalla Benetta, Soprano / Maxim Mironov, Gheorghe Vlad, Tenor / Luca Dall’Amico, Zong Shi, Bass / Vittorio Prato, Baritone / 8.660417-18 Bianca e Gernando 2 Discs Marina Viotti, Mar Campo, Mezzo-soprano / Poznan Camerata Bach 7 30099 04177 5 Choir / Virtuosi Brunensis / Antonino Fogliani 8.550605 Favourite Soprano Arias Luba Orgonášová, Soprano / Slovak RSO / Will Humburg Disc 0 730099 560528 Maria Callas, Rina Cavallari, Gina Cigna, Rosa Ponselle, Soprano / Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Ebe Stignani, Mezzo-soprano / Marion Telva, Contralto / Giovanni Breviario, Paolo Caroli, Mario Filippeschi, Francesco Merli, Tenor / Tancredi Pasero, 8.110325-27 Norma [3 Discs] 3 Discs Ezio Pinza, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bass / Italian Broadcasting Authority Chorus and Orchestra, Turin / Milan La Scala Chorus and 0 636943 132524 Orchestra / New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / BELLINI, Vincenzo Vittorio -

Lps-Vocal Recitals All Just About 1-2 Unless Otherwise Described

LPs-Vocal Recitals All just about 1-2 unless otherwise described. Single LPs unless otherwise indicated. Original printed matter with sets should be included. 4208. LUCINE AMARA [s]. RECITAL. With David Benedict [pno]. Music of Donaudy, De- bussy, de Falla, Szulc, Turina, Schu- mann, Brahms, etc. Cambridge Stereo CRS 1704. $8.00. 4229. AGNES BALTSA [ms]. OPERA RECITAL. From Cenerentola, Il Barbiere di Siviglia, La Favorita, La Clemenza di Tito , etc. Digital stereo 067-64-563 . Cover signed by Baltza . $10.00. 4209. ROLF BJÖRLING [t]. SONGS [In Swedish]. Music of Widéem, Peterson-Berger, Nord- qvist, Sjögren, etc. The vocal timbre is quite similar to that of Papa. Odeon PMES 552. $7.00. 3727. GRACE BUMBRY [ms]. OPERA ARIAS. From Camen, Sappho, Samson et Dalila, Dr. Frieder Weissmann and Don Carlos, Cavalleria Rustican a, etc. Sylvia Willink-Quiel, 1981 Deut. Gram. Stereo SLPM 138 826. Sealed . $7.00. 4213. MONTSERAAT CABALLÉ [s]. ROSSINI RARITIES. Orch. dir. Carlo Felice Cillario. From Armida, Tancredi, Otello, Stabat Mater, etc. Rear cover signed by Caballé . RCA Victor LSC-3015. $12.00. 4211. FRANCO CORELLI [t] SINGS “GRANADA” AND OTHER ROMANTIC SONGS. Orch. dir Raffaele Mingardo. Capitol Stereo SP 8661. Cover signed by Corelli . $15.00. 4212. PHYLLLIS CURTIN [s]. CANTIGAS Y CANCIONES OF LATIN AMERICA. With Ryan Edwards [pno]. Music of Villa-Lobos, Tavares, Ginastera, etc. Rear cover signed by Curtin. Vanguard Stereolab VSD-71125. $10.00. 4222. EILEEN FARRELL [s]. SINGS FRENCH AND ITALIAN SONGS. Music of Respighi, Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Debussy. Piano acc. George Trovillo. Columbia Stereo MS- 6524. Factory sealed. $6.00. -

NEW YORK CRITICS REVIEW MARIA CALLAS and RENATA TEBALDI: a Study in Critical Approaches to the Inter-Relationship of Singing

NEW YORK CRITICS REVIEW MARIA CALLAS AND RENATA TEBALDI: A Study in Critical Approaches to the Inter-relationship of Singing and Acting in Opera by MarikolVan Campen B. A., University orBritish Columbia, 1968 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies Department of Theatre, Faculty of Arts, University of British Columbia We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1977 1977 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of THEATRE The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date Oct. 5, 1977 i ABSTRACT The following study is an analysis of New York reviews of performances of Maria Callas and Renata Tebaldi which attempts to discover what opera critics feel to be the most effective artistic balance between singing and acting in opera. Callas and Tebaldi have been chosen as the subjects of the reviews because of their renown as singers, the closely coinciding cir• cumstances of their careers and the polarities which they represented in the issue of acting versus singing in operatic performance. -

COLORATURA and LYRIC COLORATURA SOPRANO

**MANY OF THESE SINGERS SPANNED MORE THAN ONE VOICE TYPE IN THEIR CAREERS!** COLORATURA and LYRIC COLORATURA SOPRANO: DRAMATIC SOPRANO: Joan Sutherland Maria Callas Birgit Nilsson Anna Moffo Kirstin Flagstad Lisette Oropesa Ghena Dimitrova Sumi Jo Hildegard Behrens Edita Gruberova Eva Marton Lucia Popp Lotte Lehmann Patrizia Ciofi Maria Nemeth Ruth Ann Swenson Rose Pauly Beverly Sills Helen Traubel Diana Damrau Jessye Norman LYRIC MEZZO: SOUBRETTE & LYRIC SOPRANO: Janet Baker Mirella Freni Cecilia Bartoli Renee Fleming Teresa Berganza Kiri te Kanawa Kathleen Ferrier Hei-Kyung Hong Elena Garanca Ileana Cotrubas Susan Graham Victoria de los Angeles Marilyn Horne Barbara Frittoli Risë Stevens Lisa della Casa Frederica Von Stade Teresa Stratas Tatiana Troyanos Elisabeth Schwarzkopf Carolyn Watkinson DRAMATIC MEZZO: SPINTO SOPRANO: Agnes Baltsa Anja Harteros Grace Bumbry Montserrat Caballe Christa Ludwig Maria Jeritza Giulietta Simionato Gabriela Tucci Shirley Verrett Renata Tebaldi Brigitte Fassbaender Violeta Urmana Rita Gorr Meta Seinemeyer Fiorenza Cossotto Leontyne Price Stephanie Blythe Zinka Milanov Ebe Stignani Rosa Ponselle Waltraud Meier Carol Neblett ** MANY SINGERS SPAN MORE THAN ONE CATEGORY IN THE COURSE OF A CAREER ** ROSSINI, MOZART TENOR: BARITONE: Fritz Wunderlich Piero Cappuccilli Luigi Alva Lawrence Tibbett Alfredo Kraus Ettore Bastianini Ferruccio Tagliavani Horst Günther Richard Croft Giuseppe Taddei Juan Diego Florez Tito Gobbi Lawrence Brownlee Simon Keenlyside Cesare Valletti Sesto Bruscantini Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau -

The Baritone to Tenor Transition

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 2018 The Baritone to Tenor Transition John White University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation White, John, "The Baritone to Tenor Transition" (2018). Dissertations. 1586. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1586 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TENOR TO BARITONE TRANSITION by John Charles White A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved by: Dr. J. Taylor Hightower, Committee Chair Dr. Kimberley Davis Dr. Jonathan Yarrington Dr. Edward Hafer Dr. Joseph Brumbeloe ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. J. Taylor Hightower Dr. Richard Kravchak Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director of School Dean of the Graduate School December 2018 COPYRIGHT BY John Charles White 2018 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT Many notable opera singers have been virtuosic tenors; Franco Corelli, Plácido Domingo, James King, José Carreras, Ramón Vinay, Jon Vickers, and Carlo Bergonzi. Besides being great tenors, each of these singers share the fact that they transitioned from baritone to tenor. Perhaps nothing is more destructive to the confidence of a singer than to have his vocal identity or voice type challenged. -

MARIO DEL MONACO Mario Del Monaco Belongs

MARIO DEL MONACONACO – A CRITICAL APPROACH BY DANIELE GODOR, XII 2009 INTRODUCTION Mario del Monaco belongselongs to a group of singers whoho aare sacrosanct to many opera listeners.listene Too impressive are the existingexisti documents of his interpretationsations of Otello (no other tenor hasas momore recordings of the role of Otello than Del Monaco who claimed to haveha sung to role 427 times1), Radamdames, Cavaradossi, Samson, Don Josésé and so on. His technique is seenn as the non-plus-ultra by many singersgers aand fans: almost indefatigable – comparable to Lauritz Melchiorlchior in this regard –, with a solid twoo octaveocta register and capable of produciroducing beautiful, virile and ringing sound of great volume. His most importmportant teacher, Arturo Melocchi,, finallyfina became famous throughh DDel Monaco’s fame, and a new schoolscho was born: the so-called Melocchialocchians worked with the techniqueique of Melocchi and the bonus of the mostm well-established exponent of his technique – Mario del Monaco.naco. Del Monaco, the “Otello of the century”” and “the Verdi tenor” (Giancarlo del Monaco)2 is – as tthese attributes suggest – a singer almost above reproach and those critics, who pointed out someme of his shortcomings, were few. In the New York Times, the famous critic Olin Downes dubbed del MonacoM “the tenor of tenors” after del Monacoonaco’s debut as Andrea Chenier in New York.3 Forr manmany tenors, del Monaco was the great idoll and founder of a new tradition: On his CD issued by the Legato label, Lando Bartolini claims to bee a sinsinger “in the tradition of del Monaco”, and even Fabioabio ArmilA iato, who has a totally different type of voice,voi enjoys when his singing is put down to the “tradititradition of del Monaco”.4 Rodolfo Celletti however,wever, and in spite of his praise for Del Monaco’s “oddodd elelectrifying bit of phrasing”, recognized in DelDel MMonaco one of the 1 Chronologies suggest a much lower amount of performances. -

Genève L'autographe

l’autographe Genève l'autographe L’Autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201, Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in US DOLLARS, SWISS FRANCS and EUROS and do not include postage. All overseas shipment will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefits of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, PayPal, and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Images not reproduced will be provided on request Postfinance CCP 61-374302-1 3 rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: EUR: CH94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 CHF: CH94 0900 0000 6137 4302 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped with La Poste and Federal Express on request. Great opera singers p. 4 Dance and Ballet p. 33 Great opera singers 1. Licia Albanese (Bari, 1909 - Manhattan, 2014) Photograph with autograph signature of the Italian soprano as Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. (8 x 10 inch. ). $ 35/ Fr. 30/ € 28 2. Lucine Amara (Hartford, 1924) Photographic portrait of the Metropolitan Opera's American soprano as Liu in Puccini’s Turandot (1926).(8 x 10 inch.). $ 35/ Fr. 30/ € 28 3. Vittorio Arimondi (Saluzzo, 1861 - Chicago, 1928) Photographic portrait with autograph signature of the Italian bass who created the role of Pistola in Verdi’s Falstaff (1893). $ 80/ Fr. -

18.5 Vocal 78S. Sagi-Barba -Zohsel, Pp 135-170

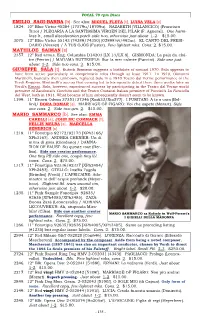

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs EMILIO SAGI-BARBA [b]. See also: MIGUEL FLETA [t], LUISA VELA [s] 1824. 10” Blue Victor 45284 [17579u/18709u]. NAZARETH [VILLANCICO] (Francisco Titto) / PLEGARIA A LA SANTISSIMA VIRGEN DEL PILAR (F. Agüeral). One harm- less lt., small discoloration patch side two, otherwise just about 1-2. $15.00. 3075. 12” Blue Victor 55143 (74389/74350) [02898½v/492ac]. EL CANTO DEL PRESI- DARIO (Alvarez) / Á TUS OJOS (Fuster). Few lightest mks. Cons . 2. $15.00. MATHILDE SAIMAN [s] 2357. 12” Red acous. Eng. Columbia D14203 [LX 13/LX 8]. GISMONDA: La paix du cloï- tre (Février) / MADAMA BUTTERFLY: Sur la mer calmée (Puccini). Side one just about 1-2. Side two cons . 2. $15.00. GIUSEPPE SALA [t]. Kutsch-Riemens suggests a birthdate of around 1870. Sala appears to have been active particularly in comprimario roles through at least 1911. 1n 1910, Giovanni Martinelli, basically then unknown, replaced Sala in a 1910 Teatro dal Verme performance of the Verdi Requiem . Martinelli’s sucess that evening led to his operatic debut there three weeks later as Verdi’s Ernani. Sala, however, experienced success by participating in the Teatro dal Verme world premiere of Zandonai’s Conchita and the Teatro Costanzi Italian premiere of Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West , both in 1911. What became of him subsequently doesn’t seem to be known. 1199. 11” Brown Odeon 37351/37346 [Xm633/Xm577]. I PURITANI: A te o cara (Bel- lini)/ DORA DOMAR [s]. MARRIAGE OF FIGARO: Voi che sapete (Mozart). Side one cons. 2. Side two gen . 2. -

Copyright by Melody Marie Rich 2003

Copyright by Melody Marie Rich 2003 The Treatise Committee for Melody Marie Rich certifies that this is the approved version of the following treatise: Pietro Cimara (1887-1967): His Life, His Work, and Selected Songs Committee: _____________________________ Andrew Dell’Antonio, Supervisor _____________________________ Rose Taylor, Co-Supervisor _____________________________ Judith Jellison _____________________________ Leonard A. Johnson _____________________________ Karl Miller _____________________________ David A. Small Pietro Cimara (1887-1967): His Life, His Work, and Selected Songs by Melody Marie Rich, B.M., M.M. Treatise Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The journey to discovering Pietro Cimara began in 1996 at a summer workshop where upon first hearing “Ben venga amore,” I instantly knew that I had to have more of Cimara’s music. Since then, the momentum to see my research through to the finish would not have continued without the help of many wonderful people whom I wish to formally acknowledge. First, I must thank my supervisor, Dr. Andrew Dell’Antonio, Associate Professor of Musicology at the University of Texas at Austin. Without your gracious help and generous hours of assistance with Italian translation, this project would not have happened. Ringraziando di cuore, cordiali saluti! To my co-supervisor, Rose Taylor, your nurturing counsel and mounds of vocal wisdom have been a valuable part of my education and my saving grace on many occasions. Thank you for always making your door open to me.