The White House and War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Custom Book List (Page 2)

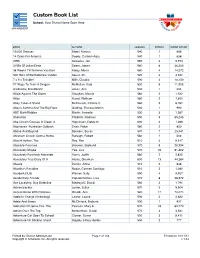

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 10,000 Dresses Ewert, Marcus 540 1 688 14 Cows For America Deedy, Carmen Agra 540 1 638 2095 Scieszka, Jon 590 3 9,974 3 NBs Of Julian Drew Deem, James 560 6 36,224 38 Weeks Till Summer Vacation Kerby, Mona 580 4 14,272 500 Hats Of Bartholomew Cubbin Seuss, Dr. 520 3 3,941 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 590 4 10,150 97 Ways To Train A Dragon McMullan, Kate 520 5 11,905 Aardvarks, Disembark! Jonas, Ann 530 1 334 Abbie Against The Storm Vaughan, Marcia 560 2 1,933 Abby Hanel, Wolfram 580 2 1,853 Abby Takes A Stand McKissack, Patricia C. 580 5 8,781 Abby's Asthma And The Big Race Golding, Theresa Martin 530 1 990 ABC Math Riddles Martin, Jannelle 530 3 1,287 Abduction Philbrick, Rodman 590 9 55,243 Abe Lincoln Crosses A Creek: A Hopkinson, Deborah 600 3 1,288 Aborigines -Australian Outback Doak, Robin 580 2 850 Above And Beyond Bonners, Susan 570 7 25,341 Abraham Lincoln Comes Home Burleigh, Robert 560 1 508 Absent Author, The Roy, Ron 510 3 8,517 Absolute Pressure Brouwer, Sigmund 570 8 20,994 Absolutely Maybe Yee, Lisa 570 16 61,482 Absolutely Positively Alexande Viorst, Judith 580 2 2,835 Absolutely True Diary Of A Alexie, Sherman 600 13 44,264 Abuela Dorros, Arthur 510 2 646 Abuelita's Paradise Nodar, Carmen Santiago 510 2 1,080 Accidental Lily Warner, Sally 590 4 9,927 Accidentally Friends Papademetriou, Lisa 570 8 28,972 Ace Lacewing: Bug Detective Biedrzycki, David 560 3 1,791 Ackamarackus Lester, Julius 570 3 5,504 Acquaintance With Darkness Rinaldi, Ann 520 17 72,073 Addie In Charge (Anthology) Lawlor, Laurie 590 2 2,622 Adele And Simon McClintock, Barbara 550 1 837 Adoration Of Jenna Fox, The Pearson, Mary E. -

Presidential Recordings of Lyndon B. Johnson (November 22, 1963-January 10, 1969) Added to the National Registry: 2013 Essay by Bruce J

Presidential Recordings of Lyndon B. Johnson (November 22, 1963-January 10, 1969) Added to the National Registry: 2013 Essay by Bruce J. Schulman (guest post)* Lyndon B. Johnson built his career--and became one of the nation’s most effective Senate leaders--through his mastery of face-to-face contact. Applying his famous “Treatment,” LBJ pleased, cajoled, flattered, teased, and threatened colleagues and rivals. He would grab people by the lapels, speak right into their faces, and convince them they had always wanted to vote the way Johnson insisted. He could share whiskey and off-color stories with some colleagues, hold detailed policy discussions with others, toast their successes, and mourn their losses. Syndicated newspaper columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak vividly described the Johnson Treatment as: supplication, accusation, cajolery, exuberance, scorn, tears, complaint, the hint of threat. It was all of these together. Its velocity was breathtaking, and it was all in one direction. Interjections from the target were rare. Johnson anticipated them before they could be spoken. He moved in close, his face a scant millimeter from his target, his eyes widening and narrowing, his eyebrows rising and falling. 1 While President Johnson never abandoned in-person persuasion, the scheduling and security demands of the White House forced him to rely more heavily on indirect forms of communication. Like Muddy Waters plugging in his electric guitar or Laurel and Hardy making the transition from silent film to talkies, LBJ became maestro of the telephone. He had the Army Signal Corps install scores of special POTUS lines (an acronym for “President of the United States”) so that he could communicate instantly with officials around the government. -

France Invades the 1961 White House

France Invades the 1961 White House Christopher Early East Carolina University Visual Arts and Design Faculty Mentor Hunt McKinnon East Carolina University Throughout its history, America‟s White House has undergone many changes through its many administrations. While a select few presidents worked to improve it, most others merely neglected it. No one, however, worked harder in restoring the White House interior than Jacqueline Kennedy, wife of President John F. Kennedy, who occupied the Executive Mansion from January 1961 until November 1963. Soon after Kennedy‟s election to the presidency in November 1960, a pregnant Jacqueline Kennedy visited the White House, as per protocol, and was given a tour of her soon-to-be-home by the outgoing First Lady, Mamie Eisenhower. “Jackie‟s first visit to the White House was her coming-out party as the next first lady.” 1 After viewing the condition of the White House, Mrs. Kennedy was appalled by its drab furniture and design. She was shocked that the White House interior, that of America‟s preeminent home, had been so woefully decorated. To her, it was nothing short of a national disgrace. Soon after taking up residence in the White House, both the President and his First Lady were struck by how depressing, drab, and tasteless the home appeared. Furniture in rooms did not match with each other, nor did paintings adorning the walls. There were no unifying themes in individual rooms or the mansion as a whole. “To her dismay she found the upstairs family quarters decorated with what she called „early Statler‟; it was so cheerless and undistinguished it wasn‟t even worthy of a second-class hotel. -

Chinese President Xi's September 2015 State Visit

Updated October 7, 2015 Chinese President Xi’s September 2015 State Visit Introduction September 26 to 28, President Xi visited the United Nations headquarters in New York for the 70th meeting of the U.N. Chinese President Xi Jinping (his family name, Xi, is General Assembly. Among other things, he announced pronounced “Shee”) made his first state visit to the United major new Chinese contributions to U.N. peacekeeping States, and his second U.S. visit as president, in September operations and military assistance to the African Union. 2015. He was the fourth leader of the People’s Republic of China to make a state visit to the United States, following in Outcomes Documents the footsteps of Li Xiannian in 1985, Jiang Zemin in 1997, and Hu Jintao in 2011. The visit came at a time of tension As has been the practice since 2011, the two countries did in the U.S.-China relationship. The United States has been not issue a joint statement. Instead, they conveyed critical of China on such issues as its alleged cyber outcomes through the two presidents’ joint press espionage, slow pace of economic reforms, island building conference; a Joint Presidential Statement on Climate in disputed waters in the South China Sea, harsh treatment Change; identical negotiated bullet points on economic of lawyers, dissidents, and ethnic minorities, and pending relations and cyber security, issued separately by each restrictive legislation on foreign organizations. Even as the country; and bullet points on other issues, issued separately White House prepared to welcome President Xi, it was and not identical in wording. -

Cabinet Room Scope and Content Notes

WHITE HOUSE TAPES CABINET ROOM CONVERSATIONS Nixon Presidential Materials Staff National Archives and Records Administration Linda Fischer Mark Fischer Ronald Sodano February 2002 NIXON WHITE HOUSE TAPES CABINET ROOM TAPES On October 16, 1997, the Nixon Presidential Materials staff opened eighty-three Nixon White House tapes containing conversations which took place within the Cabinet Room from February 16, 1971 through July 18, 1973. This release consisted of approximately 436 conversations and totaled approximately 154 hours. The Cabinet Room was one of seven locations in which conversations were surreptitiously taped. The complete Cabinet Room conversations are available to the public on reference cassettes C1 – C251 During review of the Cabinet Room tapes, approximately 78 hours of conversations were withdrawn under the provisions of the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act of 1974 (PRMPA) (44 USC 2111 note) and Executive Order (EO) 12356. These segments were re-reviewed under EO 12958 (April 17, 1995). As a result, the Nixon Presidential Materials Staff was able to open approximately 69 hours of previously restricted audio segments. The declassified segments were released on February 28, 2002, and are available as excerpted conversation segments on reference cassettes E504 – E633. These recorded White House tapes are part of the Presidential historical materials of the Nixon Administration. These materials are in the custody of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) under the provisions of the PRMPA. Access to the Nixon Presidential materials is governed by the PRMPA and its implementing public access regulations. A Brief History of the White House Taping System In February 1971, the United State Secret Service (USSS), at the request of the President, installed listening devices in the White House. -

Dolley Madison

Life Story Dolley Madison 1768–1849 expulsion from Quaker Meeting, and his wife took in boarders to make ends meet . Perhaps pressured by her father, who died shortly after, Dolley, at 22, married Quaker lawyer John Todd, whom she had once rejected . Her 11-year- old sister, Anna, lived with them . The Todds’ first son, called Payne, was born in 1791, and a second son, William, followed in 1793 . In the late summer of that year, yellow fever hit Philadelphia, and before cold weather ended the epidemic, Dolley lost four members of her family: her father-in-law, her mother-in-law, and then, on the same October day, her husband and three-month-old William . She wrote a half-finished sentence in a letter: “I am now so unwell that I can’t . ”. James Sharples Sr ., Dolley Madison, ca . 1796–1797 . Pastel on paper . Independence National Historic Park, Philadelphia . Added to her grief, Dolley faced an financial strain at the same time . Fifty extremely difficult situation . She was years later, she would face them again . a widow caring for her small son and her young sister . Men were considered Dolley’s mother went to live with a responsible for their female relatives; it was married daughter, and Dolley, Payne, one of the social side effects of coverture and Anna moved back to the family (see Resource 1) . But all the men who might home . Philadelphia was then the nation’s have cared for Dolley were gone . Her temporary capital and most sophisticated husband had left her some money in his city . -

Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021

6809 Federal Register Presidential Documents Vol. 86, No. 13 Friday, January 22, 2021 Title 3— Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021 The President Building the National Garden of American Heroes By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered as follows: Section 1. Background. In Executive Order 13934 of July 3, 2020 (Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes), I made it the policy of the United States to establish a statuary park named the National Garden of American Heroes (National Garden). To begin the process of building this new monument to our country’s greatness, I established the Interagency Task Force for Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes (Task Force) and directed its members to plan for construction of the National Garden. The Task Force has advised me it has completed the first phase of its work and is prepared to move forward. This order revises Executive Order 13934 and provides additional direction for the Task Force. Sec. 2. Purpose. The chronicles of our history show that America is a land of heroes. As I announced during my address at Mount Rushmore, the gates of a beautiful new garden will soon open to the public where the legends of America’s past will be remembered. The National Garden will be built to reflect the awesome splendor of our country’s timeless exceptionalism. It will be a place where citizens, young and old, can renew their vision of greatness and take up the challenge that I gave every American in my first address to Congress, to ‘‘[b]elieve in yourselves, believe in your future, and believe, once more, in America.’’ Across this Nation, belief in the greatness and goodness of America has come under attack in recent months and years by a dangerous anti-American extremism that seeks to dismantle our country’s history, institutions, and very identity. -

A Closer Look at James and Dolley Madison Compiled by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

A Closer Look at James and Dolley Madison Compiled by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Target Grade Level: 4–12 in United States history classes Objectives After completing this lesson, students will be better able to: • Identify and analyze key components of a portrait and relate visual elements to relevant historical context and significance • Compare and contrast the characteristics of two portraits that share similar subject matter, historical periods, and/or cultural context • Use portrait analysis to deepen their understanding of James and Dolley Madison and the roles that they played in U.S. history. Portraits James Madison by Gilbert Stuart Oil on canvas, 1804 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Virginia Dolley Madison by Gilbert Stuart Oil on canvas, 1804 White House Collection, Washington, D.C.; gift of the Walter H. & Phyllis Shorenstein Foundation in memory of Phyllis J. Shorenstein Additional Artworks For more portraits and artworks, visit the “1812: A Nation Emerges” online exhibition at http://npg.si.edu/exhibit/1812 Background Information for Teachers Information about James Madison (1751–1836) from the James Madison Museum (http://www.thejamesmadisonmuseum.org/biographies/james-madison) James Madison was born on March 16, 1751, in Port Conway, Virginia. The oldest of ten children in a distinguished planter family, he was educated by tutors and at Princeton University (then called the College of New Jersey). At a young age, Madison decided on a life in politics. He threw himself enthusiastically into the independence movement, serving on the local Committee of Safety and in the Virginia Convention, where he demonstrated his abilities for constitution-writing by framing his state constitution. -

From the American Revolution Through the American Civil War"

History 216-01: "From the American Revolution through the American Civil War" J.P. Whittenburg Fall 2009 Email: [email protected] Office: Young House (205 Griffin Avenue) Web Page: http://faculty.wm.edu/jpwhit Telephone: 757-221-7654 Office Hours: By Appointment Clearly, this isn't your typical class. For one thing, we meet all day on Fridays. For another, we will spend most of our class time "on-site" at museums, battlefields, or historic buildings. This class will concentrate on the period from the end of the American Revolution through the end of the American Civil War, but it is not at all a narrative that follows a neat timeline. I’ll make no attempt to touch on every important theme and we’ll depart from the chronological approach whenever targets of opportunities present themselves. I'll begin most classes with some sort of short background session—a clip from a movie, oral reports, or maybe something from the Internet. As soon as possible, though, we'll be into a van and on the road. Now, travel time can be tricky and I do hate to rush students when we are on-site. I'll shoot for getting people back in time for a reasonably early dinner—say 5:00. BUT there will be times when we'll get back later than that. There will also be one OPTIONAL overnight trip—to the Harper’s Ferry and the Civil War battlefields at Antietam and Gettysburg. If these admitted eccentricities are deeply troubling, I'd recommend dropping the course. No harm, no foul—and no hard feelings. -

President's Daily Diary, April 1, 1968

/HITE House Date April 1, 1968 »ENT LYNDO N B . JOHNSON DIARY the White House Monday 'resident began his day at (Place) : : Day ' Time Telephone f or t Expendi- 1 : . Activity (include visited by) ture In Out Lo LD C^ * ^ ^ j ^ ~~~^ ~ : ' ' "" } ' ' 1 -I -— .1 . 1 .., . I .. I -I • I I III I I »___ I 8:44a f <fr Edwin Weisl Sr - New York City ______ — 8:49a , f Gov. John Connally - Austin _ ' ____ | : : : : t . : ____ . , ,«__^_, , __ - ! The President walked through the Diplomatic Reception Room-- and onto the South Lawn ____ into the bright sun, toward the helicopter. He was wearing a hat and a raincoat. I . ___„_ , 9:24a I The Helicopter departed the South Lawn - ' I I The President was accompanied, by ' ^___ Sam Houston Johnson , __ ' ! Horace Busby ______ x • ' __ : Douglass Cater « - i Larry Temple - I George Christian I Jim Jones _______ I Kenny Gaddis : ' _. __ | Dr. George Burkley ^ I ; mf """ ~~~ * . i i ________ _ | j The President -- immediately upon takeoff - showed Busby and Cater the ; \ telegram he had just received from Sen. Robt Kennedy. The President himselt '•. | made no comment. just handed it to the two men. and Busby said, "He wants to see you like he wanted to see McNamara. " 'HITE Hoosi Dat e Apri l 1 , 196 8 ENT LYNDO N B . JOHNSO N WARY th e Whit e House Monda y 'resident bega n hi s da y a t (Place ) - — Day_ _ .. Time Telephon e . Activity (include visited by) in Ou t L o LD The President also read a memo from Rosto w outlining the difficulties tha t Rostow "" ""see s this morning wit h Sout h VietNam. -

Teaching Skills with Children's Literature As Mentor Text Presented at TLA 2012

Teaching Skills with Children's Literature as Mentor Text Presented at TLA 2012 List compiled by: Michelle Faught, Aldine ISD, Sheri McDonald, Conroe ISD, Sally Rasch, Aldine ISD, Jessica Scheller, Aldine ISD. April 2012 2 Enhancing the Curriculum with Children’s Literature Children’s literature is valuable in the classroom for numerous instructional purposes across grade levels and subject areas. The purpose of this bibliography is to assist educators in selecting books for students or teachers that meet a variety of curriculum needs. In creating this handout, book titles have been listed under a skill category most representative of the picture book’s story line and the author’s strengths. Many times books will meet the requirements of additional objectives of subject areas. Summaries have been included to describe the stories, and often were taken directly from the CIP information. Please note that you may find some of these titles out of print or difficult to locate. The handout is a guide that will hopefully help all libraries/schools with current and/or dated collections. To assist in your lesson planning, a subjective rating system was given for each book: “A” for all ages, “Y for younger students, and “O” for older students. Choose books from the list that you will feel comfortable reading to your students. Remember that not every story time needs to be a teachable moment, so you may choose to use some of the books listed for pure enjoyment. The benefits of using children’s picture books in the instructional setting are endless. The interesting formats of children’s picture books can be an excellent source of information, help students to understand vocabulary words in different contest areas, motivate students to learn, and provide models for research and writing. -

Henry Kissinger: the Emotional Statesman*

barbara keys Bernath Lecture Henry Kissinger: The Emotional Statesman* “That poor fellow is an emotional fellow,” a fretful Richard Nixon observed about Henry Kissinger on Christmas Eve 1971. The national security adviser had fallen into one of his typical postcrisis depressions, anguished over public criticism of his handling of the Indo-Pakistani War. In a long, meandering conversation with aide John Ehrlichman, Nixon covered many topics, but kept circling back to his “emotional” foreign policy adviser. “He’s the kind of fellow that could have an emotional collapse,” he remarked. Ehrlichman agreed. “We just have to get him some psychotherapy,” he told the president. Referring to Kissinger as “our major problem,” the two men recalled earlier episodes of Kissinger’s “impossible” behavior. They lamented his inability to shrug off criticism, his frequent mood swings, and his “emotional reactions.” Ehrlichman speculated that Nelson Rockefeller’s team had “had all kind of problems with him,” too. Nixon marveled at how “ludicrous” it was that he, the president— beset with enormous problems on a global scale—had to spend so much time “propping up this guy.” No one else, Nixon said, would have put up with “his little tantrums.”1 Kissinger’s temper tantrums, jealous rages, and depressions frequently frus- trated and bewildered the president and his staff. Kissinger habitually fell into a state of self-doubt when his actions produced public criticism. When his support for the Cambodian invasion elicited a media frenzy, for example, Kissinger’s second-in-command, Al Haig, went to Nixon with concerns about his boss’s “very emotional and very distraught” state.2 Journalists often found what William Safire called “Kissinger’s anguish—an emotion dramatized by the man’s ability to let suffering show in facial expressions and body *I am grateful to Frank Costigliola and TomSchwartz for comments on a draft of this essay, and to Frank for producing the scholarship that helped inspire this project.