LESSON PLAN: Use of the Motion Picture, “Gandhi” Objectives: 1. to Acquaint Students with the Life and Philosophy of Mohand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life Ad Afterlife of the Mahatma

Indi@logs Vol 1 2014, pp. 103-122, ISSN: 2339-8523 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ GADHI ISM VS . G ADHI GIRI : THE LIFE AD AFTERLIFE OF THE MAHATMA 1 MAKARAND R. P ARANJAPE Jawaharlal Nehru University [email protected] Received: 11-05-2013 Accepted: 01-10-2013 ABSTRACT This paper, which contrasts Rajkumar Hirani’s Lage Raho Munna Bhai (2006) with Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982), is as much a celebration of Bollywood as of Gandhi. It is to the former that the credit for most effectively resurrecting the Mahatma should go, certainly much more so than to Gandhians or academics. For Bollywood literally revives the spirit of Gandhi by showing how irresistibly he continues to haunt India today. Not just in giving us Gandhigiri—a totally new way of doing Gandhi in the world—but in its perceptive representation of the threat that modernity poses to Gandhian thought is Lage Raho Munna Bhai remarkable. What is more, it also draws out the distinction between Gandhi as hallucination and the real afterlife of the Mahatma. The film’s enormous popularity at the box office—it grossed close to a billion rupees—is not just an index of its commercial success, but also proof of the responsive chord it struck in Indian audiences. But it is not just the genius and inventiveness of Bollywood cinema that is demonstrated in the film as much as the persistence and potency of Gandhi’s own ideas, which have the capacity to adapt themselves to unusual circumstances and times. Both Richard Attenborough’s Oscar-winning epic, and Rajkumar Hirani’s Lage Raho Munna Bhai show that Gandhi remains as media-savvy after his death as he was during his life. -

Gandhi Sites in Durban Paul Tichmann 8 9 Gandhi Sites in Durban Gandhi Sites in Durban

local history museums gandhi sites in durban paul tichmann 8 9 gandhi sites in durban gandhi sites in durban introduction gandhi sites in durban The young London-trained barrister, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 1. Dada Abdullah and Company set sail for Durban from Bombay on 19 April 1893 and arrived in (427 Dr Pixley kaSeme Street) Durban on Tuesday 23 May 1893. Gandhi spent some twenty years in South Africa, returning to India in 1914. The period he spent in South Africa has often been described as his political and spiritual Sheth Abdul Karim Adam Jhaveri, a partner of Dada Abdullah and apprenticeship. Indeed, it was within the context of South Africa’s Co., a firm in Porbandar, wrote to Gandhi’s brother, informing him political and social milieu that Gandhi developed his philosophy and that a branch of the firm in South Africa was involved in a court practice of Satyagraha. Between 1893 and 1903 Gandhi spent periods case with a claim for 40 000 pounds. He suggested that Gandhi of time staying and working in Durban. Even after he had moved to be sent there to assist in the case. Gandhi’s brother introduced the Transvaal, he kept contact with friends in Durban and with the him to Sheth Abdul Karim Jhaveri, who assured him that the job Indian community of the City in general. He also often returned to would not be a difficult one, that he would not be required for spend time at Phoenix Settlement, the communitarian settlement he more than a year and that the company would pay “a first class established in Inanda, just outside Durban. -

Chapter I Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Nonviolence is the pillar of Gandhi‘s life and work. His concept of nonviolence was based on cultivating a particular philosophical outlook and was integrally associated with truth. For him, nonviolence not just meant refraining from physical violence interpersonally and nationally but refraining from the inner violence of the heart as well. It meant the practice of active love towards one‘s oppressor and enemies in the pursuit of justice, truth and peace; ―Nonviolence cannot be preached‖ he insisted, ―It has to be practiced.‖ (Dear John, 2004). Non Violence is mightier than violence. Gandhi had studied very well the basic nature of man. To him, "Man as animal is violent, but in spirit he is non-violent.‖ The moment he awakes to the spirit within, he cannot remain violent". Thus, violence is artificial to him whereas non-violence has always an edge over violence. (Gandhi, M.K., 1935). Mahatma Gandhi‘s nonviolent struggle which helped in attaining independence is the biggest example. Ahimsa (nonviolence) has been part of Indian religious tradition for centuries. According to Mahatma Gandhi the concept of nonviolence has two dimensions i.e. nonviolence in action and nonviolence in thought. It is not a negative virtue rather it is positive state of love. The underlying principle of non- violence is "hate the sin, but not the sinner." Gandhi believes that man is a part of God, and the same divine spark resides in all men. Since the same spirit resides in all men, the possibility of reforming the meanest of men cannot be ruled out. -

Mahatma Gandhi

CHAPTER 1 MAHATMA GANDHI To be Human is to be One with God Mahatma Gandhi: A brief outline The best sources for a detailed life of Mahatma Gandhi are his autobiography and the many collected works that appear under his name. In brief, he was born in India in 1869, was married at the age of 13, and traveled to study law in England at the age of 19. His first trip to South Africa was in 1893 at the request of Indians in that country. While at Pietermaritzburg he was ejected from the train for sitting in a compartment reserved for whites. He sided with the British during the Boer War (although his sympathies lay with the Boers). During the Zulu War he formed the Ambulance Corps to help wounded soldiers, but also to show his loyalty to the British Empire. After the Zulu War, Gandhi took a vow of celibacy, and began using nonviolence as way for attaining rights for Indians in South Africa. It was after the Zulu War that he began articulating the goal of life as attaining moksha, or oneness with God. It was also in South Africa that the word Satyagraha was coined. After 21 years in South Africa, Gandhi left for India and worked for the independence of India from Britain. He was assassinated in 1948. Needless to say, this paragraph gives a brief timeline of Gandhi. Again, The Autobiography and Collected Works (which appear in the text as CWMG for Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi) offer detailed information on the Mahatma. The depiction of Gandhi’s philosophy and understanding of human nature in this chapter differs from most works on Gandhi by deliberately focusing on the influence of non-western cultures and his rejection and critique of capitalism Most Gandhian scholars present him as a person desperately trying to assimilate into the dominant capitalist culture, or mute his criticisms of capitalism. -

Formative Years

CHAPTER 1 Formative Years Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a seaside town in western India. At that time, India was under the British raj (rule). The British presence in India dated from the early seventeenth century, when the English East India Company (EIC) first arrived there. India was then ruled by the Mughals, a Muslim dynasty governing India since 1526. By the end of the eighteenth century, the EIC had established itself as the paramount power in India, although the Mughals continued to be the official rulers. However, the EIC’s mismanagement of the Indian affairs and the corruption among its employees prompted the British crown to take over the rule of the Indian subcontinent in 1858. In that year the British also deposed Bahadur Shah, the last of the Mughal emperors, and by the Queen’s proclamation made Indians the subjects of the British monarch. Victoria, who was simply the Queen of England, was designated as the Empress of India at a durbar (royal court) held at Delhi in 1877. Viceroy, the crown’s representative in India, became the chief executive-in-charge, while a secretary of state for India, a member of the British cabinet, exercised control over Indian affairs. A separate office called the India Office, headed by the secretary of state, was created in London to exclusively oversee the Indian affairs, while the Colonial Office managed the rest of the British Empire. The British-Indian army was reorganized and control over India was established through direct or indirect rule. The territories ruled directly by the British came to be known as British India. -

Title a Revival of Gandhism in India? : Lage Raho Munna Bhai and Anna

A Revival of Gandhism in India? : Lage Raho Munna Bhai and Title Anna Hazare Author(s) ISHIZAKA, Shinya Citation INDAS Working Papers (2013), 12: 1-13 Issue Date 2013-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/178768 Right Type Research Paper Textversion author Kyoto University INDAS Working Papers No. 12 September 2013 A Revival of Gandhism in India? Lage Raho Munna Bhai and Anna Hazare Shinya ISHIZAKA 人間文化研究機構地域研究推進事業「現代インド地域研究」 NIHU Program Contemporary India Area Studies (INDAS) A Revival of Gandhism in India? Lage Raho Munna Bhai and Anna Hazare Shinya Ishizaka∗ A 2006 record hit Bollywood comedy film, Lage Raho Munna Bhai, where a member of the Mumbai mafia began to engage in Gandhigiri (a term meaning the tenets of Gandhian thinking, popularised by this film) by quitting dadagiri (the life of a gangster) in order to win the love of a lady, was sensationalised as the latest fashion in the revival of Gandhism. Anna Hazare (1937-), who has used fasting as an effective negotiation tactic in the anti-corruption movement in 2011, has been more recently acclaimed as a second Gandhi. Indian society has undergone a total sea change since the Indian freedom fighter M. K. Gandhi (1869-1948) passed away. So why Gandhi? And why now? Has the recent phenomena of the success of Munna Bhai and the rise of Anna’s movement shown that people in India today still recall Gandhi’s message? This paper examines the significance of these recent phenomena in the historical context of Gandhian activism in India after Gandhi. It further analyses how contemporary Gandhian activists perceive Anna Hazare and his movement, based upon interviews conducted with them during fieldwork in India in the period August-September 2011. -

GW 131 Spring 2017

The Gandhi Way Tavistock Square, London 30 January 2017 (Photo by John Rowley) Newsletter of the Gandhi Foundation No.131 Spring 2017 ISSN 1462-9674 £2 1 Gandhi Foundation Summer Gathering 2017 Theme: Inspired by Gandhi 22 July - 29 July 2017 St Christopher School, Barrington Road, Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire SG6 3JZ Further details: Summer Gathering, 2 Vale Court, Weybridge KT13 9NN or Telephone: 01932 841135; [email protected] Gandhi Foundation Annual Lecture 2017 to be given by Satish Kumar Saturday 30 September Venue in London to be announced later An International Conference on Mahatma Gandhi in the 21st century: Gandhian Themes and Values Friday 28 April 2017 at the Wellcome Trust Conference Centre, 183 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE Organised by Narinder Kapur & Caroline Selai, University College London Further details on page 23 Contents Climate Change – A Burning Issue Jane Sill An Experiment in Love: Maria Popova Martin Luther KIng on the Six Pillars of Nonviolent Resistance Mahatma Gandhi and Shrimad Rajchandraji Reviews: Pax Gandhiana (Anthony Parel) William Rhind Selected Works of C Rajagopalachari II Antony Copley Obituaries: Arya Bhardwaj Gerd Ledermann 2 Climate Change – A Burning Issue Jane Sill This was the title of this year's annual multifaith gathering which took place on 28th January at Kingsley Hall where Gandhi Ji had stayed in 1931 while attending the Round Table Conference. The title had been chosen some time ago but, in view of the drastic change in US policy, it could not have been a more fitting subject. Often pushed aside in the light of apparently more pressing issues, this is a subject which unfortunately is bound to come into higher profile as the results of global warming become more evident – unless of course there are serious policy changes worldwide. -

68-77 M.K. Gandhi Through Western Lenses

68 M.K.Gandhi through Western Lenses: Romain Rolland’s Mahatma Gandhi: The Man Who Became One With the Universal Being Madhavi Nikam Volume 1 : Issue 06, October 2020 Volume Department of English, Ramchand Kimatram Talreja College, Ulhasnagar [email protected] Sambhāṣaṇ 69 Abstract: Gandhi, an Orientalist could find a sublime place in the heart and history of the Westerners with the literary initiative of a French Nobel Laureate Romain Rolland. Rolland was a French writer, art historian and mystic who bagged Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915. Rolland’s pioneering biography (in the West) on Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi published in 1924, not only made him popular overnight but also restructured the Indian figure in the minds of people. Since the publication of his biography, number of biographies on Gandhi appeared in the market from various corners of the world. Rolland himself being a pacifist was impressed with Gandhi, a man with different life style and unique modus operandi. Pacifism has greatly benefited from the biographical and historiographical revival by contribution of such great authors. Gandhi’s firm belief in the democratic and four fundamental principles of Truth (Satya), non-violence (Ahimsa), welfare of all (Sarvodaya) and peaceful protest (Satyagraha) left an indelible impact on the writer which helped him to express his resentment at imperialism in his later works. The paper would attempt to reassess Gandhi as a philosopher, and revolutionary in the context with Romain Rolland’s correspondence with Gandhi written in 1923-24. The paper will be a sincere effort to explore Rolland ‘s first but lasting impression of Gandhi who offered attractive regenerative possibilities for Volume 1 : Issue 06, October 2020 Volume Europe after the great war. -

1. RAJKOT the Struggle in Rajkot Has a Personal Touch About It for Me

1. RAJKOT The struggle in Rajkot has a personal touch about it for me. It was the place where I received all my education up to the matricul- ation examination and where my father was Dewan for many years. My wife feels so much about the sufferings of the people that though she is as old as I am and much less able than myself to brave such hardships as may be attendant upon jail life, she feels she must go to Rajkot. And before this is in print she might have gone there.1 But I want to take a detached view of the struggle. Sardar’s statement 2, reproduced elsewhere, is a legal document in the sense that it has not a superfluous word in it and contains nothing that cannot be supported by unimpeachable evidence most of which is based on written records which are attached to it as appendices. It furnishes evidence of a cold-blooded breach of a solemn covenant entered into between the Rajkot Ruler and his people.3 And the breach has been committed at the instance and bidding of the British Resident 4 who is directly linked with the Viceroy. To the covenant a British Dewan5 was party. His boast was that he represented British authority. He had expected to rule the Ruler. He was therefore no fool to fall into the Sardar’s trap. Therefore, the covenant was not an extortion from an imbecile ruler. The British Resident detested the Congress and the Sardar for the crime of saving the Thakore Saheb from bankruptcy and, probably, loss of his gadi. -

In the High Court of Judicature at Madras Dated

W.P.No.7501 of 2020 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MADRAS DATED : 21.04.2020 CORAM THE HONOURABLE Mr.JUSTICE M.SATHYANARAYANAN AND THE HONOURABLE Mr.JUSTICE M.NIRMAL KUMAR W.P.No.7501 of 2020 T.Sivakumar ... Petitioner Versus 1.The Secretary to Government of India, Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, A-Wing, Sasthri Bhavan, New Delhi-110 001. 2.The Chairman, Indian Oil Corporation Ltd., Indian Oil Bhavan, G-9, Ali Yavur Jung Marg, Bandra (East), Mumbai-400 051. 3.The Chief Managing Director, Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd., Bharat Bhavan, 4 & 6 Currimbhoy Road, Ballard Estate, Mumbai-400 001. 1/6 W.P.No.7501 of 2020 4.The Chief Managing Director, Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Ltd., Hindustan Bhavan, 3rd Floor, No.8, Shoorji Vallabhdas Mard, Balard Estate, Mumbai-400 001. 5.The Regional Manager, Indian Oil Corporation Ltd., Indian Oil Bhavan, 139, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Nungambakkam High Road, Chennai-600 034. 6.The Regional Manager, Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd., No.1, Rangananthan Garden, 11th Main Road, Anna Nagar, Chennai-600 040. 7.The Regional Manager, Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Ltd., Thalamuthu Natarajan Building, 1, Gandhi Irwin Road, Chennai-600 008. 8.The Principal Secretary, Government of Tamil Nadu, Health and Family Welfare Department, St.George Fort, Chennai-600 009. 9.The Nodal Officer, Emergency Operations Control Room, O/o Directorate of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, DMS Campus, Chennai-600 006. ... Respondents 2/6 W.P.No.7501 of 2020 Prayer:- Writ petition has been filed under Article 226 of -

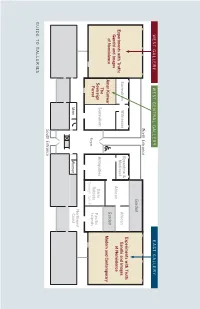

Gandhi and Images WEST GALLERY of Nonviolence Gandhi and Images of Nonviolence Amar Kanwar Surrealism Sovereign Forest the WEST CENTRAL GALLERY

The Menil Collection The October 2, 2014–February 1, 2015 EXPERIMENTS WITH TRUTH Gandhi and Gandhi ofImages Nonviolence WEST GALLERY WEST CENTRAL GALLERY EAST GALLERY North Entrance Garden Experiments with Truth: Byzantine & Surrealism Witnesses African Gandhi and Images Experiments with Truth: Medieval of Nonviolence Gandhi and Images African of Nonviolence Garden Amar Kanwar Modern and Contemporary The Surrealism Antiquities Dario Sovereign Pacific Robleto Forest Foyer Islands Through Jan. 4 Northwest Men Women Coast South Entrance GUIDE TO GALLERIES EXPERIMENTS WITH TRUTH Gandhi and Images of Nonviolence The Menil Collection October 2, 2014–February 1, 2015 The Menil Collection June 28–August 31, 2014 1 WEST, WEST CENTRAL, and EAST GALLERIES EXPERIMENTS WITH TRUTH: GANDHI AND IMAGES OF NONVIOLENCE ohandas K. Gandhi (born India, October 2, 1869) was the twen- tieth century’s greatest advocate for taking peaceful direct action against oppression and injustice. As a London-trained lawyer fighting discrimination in South Africa, he pioneered techniques Mof nonviolent resistance based on ahimsa (literally “non-harming”) and his own concept of “truth-force,” satya + agraha (also called “soul force”), and then from the mid 1910s until his assassination in 1948 Gandhi led their deployment in the mass struggle against British rule in colonial India. He coined the term satyagraha to name “the force which is born of truth and love or nonviolence.” A prolific writer, Gandhi began to tell this story in his 1927/29 autobiography, My Experiments with Truth. Experiments with Truth: Gandhi and Images of Nonviolence explores the resonance of Gandhi’s ethics of satyagraha in the visual arts. -

Gandhian Concept of Truth and Non-Violence

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 18, Issue 4 (Nov. - Dec. 2013), PP 67-69 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Gandhian Concept of Truth and Non-Violence Arpana Ramchiary. Assistant Professor Department: Philosophy Barpeta Girls’ College, Barpeta Country: India Abstract: Gandhi was a great supporter of Truth and Non-violence. He had a great importance to the concept of Truth and Non-Violence.Truth or Satya, Ahimsa or Non-Violance are foundation of Ganghi’s philosophy. The word ‘Non-violence’ is a translation of the Sanskrit term ‘Ahimsa’. He stated that in its positive form, ‘Ahimsa’ means ‘The largest love, the greatest charity’. Moreover he stated that Ahimsa binds us to one another and also to God. So it is a unifying agent. Gandhi wrote, ‘Ahimsa and Love are one and the same thing’. According to Gandhi the word ‘Satya’ comes from the word ‘Sat’ which means ‘to exist’. So by the term ‘Satya’ Gandhi also means that which is not only existent but also true. Gandhi said that Truth and Non-Violence are the two sides of a same coin, or rather a smooth unstamped metallic disc. Who can say, which is the obverse, and which the reverse? Ahimsa is the means; Truth is the end. I will discuss the Gandhian concept of Truth and Non-Violence elaborately in this paper. Keywords: Truth or Satyagraha, Non-Violence or Ahimsa, Characteristics of Non-Violence, Qualities and Characteristics of Satyagrahi. Identification of Truth and God. I. Introduction: Gandhi was a great supporter of Truth and Non-violence.