Myanmar Remittances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange As of December 31, 2018

TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2018 COUNTRY-CURRENCY F.C. TO $1.00 AFGHANISTAN - AFGHANI 74.5760 ALBANIA - LEK 107.0500 ALGERIA - DINAR 117.8980 ANGOLA - KWANZA 310.0000 ANTIGUA - BARBUDA - E. CARIBBEAN DOLLAR 2.7000 ARGENTINA-PESO 37.6420 ARMENIA - DRAM 485.0000 AUSTRALIA - DOLLAR 1.4160 AUSTRIA - EURO 0.8720 AZERBAIJAN - NEW MANAT 1.7000 BAHAMAS - DOLLAR 1.0000 BAHRAIN - DINAR 0.3770 BANGLADESH - TAKA 84.0000 BARBADOS - DOLLAR 2.0200 BELARUS - NEW RUBLE 2.1600 BELGIUM-EURO 0.8720 BELIZE - DOLLAR 2.0000 BENIN - CFA FRANC 568.6500 BERMUDA - DOLLAR 1.0000 BOLIVIA - BOLIVIANO 6.8500 BOSNIA- MARKA 1.7060 BOTSWANA - PULA 10.6610 BRAZIL - REAL 3.8800 BRUNEI - DOLLAR 1.3610 BULGARIA - LEV 1.7070 BURKINA FASO - CFA FRANC 568.6500 BURUNDI - FRANC 1790.0000 CAMBODIA (KHMER) - RIEL 4103.0000 CAMEROON - CFA FRANC 603.8700 CANADA - DOLLAR 1.3620 CAPE VERDE - ESCUDO 94.8800 CAYMAN ISLANDS - DOLLAR 0.8200 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC - CFA FRANC 603.8700 CHAD - CFA FRANC 603.8700 CHILE - PESO 693.0800 CHINA - RENMINBI 6.8760 COLOMBIA - PESO 3245.0000 COMOROS - FRANC 428.1400 COSTA RICA - COLON 603.5000 COTE D'IVOIRE - CFA FRANC 568.6500 CROATIA - KUNA 6.3100 CUBA-PESO 1.0000 CYPRUS-EURO 0.8720 CZECH REPUBLIC - KORUNA 21.9410 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO- FRANC 1630.0000 DENMARK - KRONE 6.5170 DJIBOUTI - FRANC 177.0000 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC - PESO 49.9400 ECUADOR-DOLARES 1.0000 EGYPT - POUND 17.8900 EL SALVADOR-DOLARES 1.0000 EQUATORIAL GUINEA - CFA FRANC 603.8700 ERITREA - NAKFA 15.0000 ESTONIA-EURO 0.8720 ETHIOPIA - BIRR 28.0400 -

“Modi Effect”: Investigating the Effect of Demonetization on Currency

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2017 The “Modi Effect”: Investigating the Effect of Demonetization on Currency Demand and the Size of the Underground Economy in India Sanjana Sankaran Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Sankaran, Sanjana, "The “Modi Effect”: Investigating the Effect of Demonetization on Currency Demand and the Size of the Underground Economy in India" (2017). CMC Senior Theses. 1647. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1647 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College The “Modi Effect”: Investigating the Effect of Demonetization on Currency Demand and the Size of the Underground Economy in India SUBMITTED TO Professor Eric Helland AND Professor Richard Burdekin BY Sanjana Sankaran for Senior Thesis Spring 2017 April 24, 2017 Table of Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5 II. Background .......................................................................................................................... -

Myanmar Business Guide for Brazilian Businesses

2019 Myanmar Business Guide for Brazilian Businesses An Introduction of Business Opportunities and Challenges in Myanmar Prepared by Myanmar Research | Consulting | Capital Markets Contents Introduction 8 Basic Information 9 1. General Characteristics 10 1.1. Geography 10 1.2. Population, Urban Centers and Indicators 17 1.3. Key Socioeconomic Indicators 21 1.4. Historical, Political and Administrative Organization 23 1.5. Participation in International Organizations and Agreements 37 2. Economy, Currency and Finances 38 2.1. Economy 38 2.1.1. Overview 38 2.1.2. Key Economic Developments and Highlights 39 2.1.3. Key Economic Indicators 44 2.1.4. Exchange Rate 45 2.1.5. Key Legislation Developments and Reforms 49 2.2. Key Economic Sectors 51 2.2.1. Manufacturing 51 2.2.2. Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry 54 2.2.3. Construction and Infrastructure 59 2.2.4. Energy and Mining 65 2.2.5. Tourism 73 2.2.6. Services 76 2.2.7. Telecom 77 2.2.8. Consumer Goods 77 2.3. Currency and Finances 79 2.3.1. Exchange Rate Regime 79 2.3.2. Balance of Payments and International Reserves 80 2.3.3. Banking System 81 2.3.4. Major Reforms of the Financial and Banking System 82 Page | 2 3. Overview of Myanmar’s Foreign Trade 84 3.1. Recent Developments and General Considerations 84 3.2. Trade with Major Countries 85 3.3. Annual Comparison of Myanmar Import of Principal Commodities 86 3.4. Myanmar’s Trade Balance 88 3.5. Origin and Destination of Trade 89 3.6. -

The Impact of the Exchange Rate Unification on Trade Balance in Myanmar

THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE BALANCE IN MYANMAR By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2016 THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE BALANCE IN MYANMAR By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2016 Professor Jong-Il YOU THE IMPACT OF THE EXCHANGE RATE UNIFICATION ON TRADE By WIN, Zar Kyi THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY Committee in charge: Professor Jong-Il YOU, Supervisor Professor Chrysostomos TABAKIS Professor Jin Soo LEE Approval as of December, 2016 ABSTRACT This study analyzes the impacts of the exchange rate unification on the trade balance in Myanmar based on Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Model. This paper’s main objective is to determine whether the exchange rate has positive or negative effects on the trade balance. This study has discovered that the exchange rate unification has a positive effect on the trade balance in the long run. Additionally, this study finds that Exchange Rate and Foreign Direct Investment have positive effects on the trade balance while GDP growth rate and Inflation has negative impact in the long run. As a policy implication, this study suggests that the government should focus on economic stability and effective monetary policies within the country. -

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Country Profile

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Country Profile Region: East Asia & Pacific (Known as Southeast Asia) Country: The Republic of Union of Myanmar Capital: Naypyidaw Largest City: Yangon (7,355,075 in 2014) Currency: Myanmar Kyat Population: 7 million (2017) GNI Per Capital: (U$$) 1,293 (2017) GDP: $94.87 billion (2017) GDP Growth: 9.0% (2017) Inflation: 10.8% 2017 (The World Bank, 2016) Language: Myanmar, several dialects and English Religion: Over 80 percent of Myanmar Theravada Buddhism. There are Christians, Muslims, Hindus, and some animists. Business Hours: Banks: 09:30 – 15:00 Mon –Fri Office: 09:30-16:00 Mon-Fri Airport Tax: 10 US Dollars for departure at international gates Customs: Foreign currencies (above USD 10000), jewelry, cameras And electronic goods must be declared to the customs at The airport. Exports of antiques and archaeologically Valuable items are prohibited. 2.2 Myanmar Tourism Overview Myanmar has been recorded as one of Asia’s most prosperous economies in the region before World War II and expected to gain rapid industrialization. The country belongs rich natural resources and one of most educated nations in Southeast Asia. However, Myanmar economic was getting worst after military coup in 1962, which transform to be one of the poorest nations in the region. “Then military government centrally planned and inward looking strategies such as nationalization of all major industries and import-substitution polices had long been pursued (Ni Lar, 2012)”. These strategies were laydown under General Nay Win leadership theory so called “Burmese Way to Socialism”. Since then, the country economic getting into problems such as ‘inactive in industrial production, high inflection, resign living cost, and macroeconomic mismanagement’. -

Social Science and the HUMANITIES an Introductory Course for Myanmar Learners

Social Science and THE HUMANITIES an introductory course for Myanmar learners Stan Jagger | Matthew Simpson Student's Book yHkESdyfwdkuftrnf a&TyHkESdyfwdkuf (NrJ - 00210) trSwf (153^155)? opfawmatmufvrf;? armifav;0if;&yfuGuf? tvHkNrdKUe,f? &efukefNrdKU xkwfa0ol OD;atmifjrwfpdk; pmaywdkuftrnf rkcfOD;pmay trSwf (105-A)? &wemNrdKifvrf;? &wemNrdKiftdrf,m trSwf (1) &yfuGuf? urm&GwfNrdKUe,f? &efukefwdkif;a'oBuD; zkef; - 09 780 303 823? 09 262 656 949 yHkESdyfrSwfwrf; xkwfa0jcif;vkyfief; todtrSwfjyK vufrSwftrSwf - 01947 yHkESdyfjcif; yxrBudrf? tkyfa& 3500 Edk0ifbmv? 2018 ckESpf . *suf*g pwef? ruf(wf)wD/ Social Science and the Humanities, Student's Book. pwef*suf*g? ruf(wf)wD/ &efukef? rkcfOD;pmtkyfwdkuf? 2018/ pm? pifwDrDwm/ rl&if;trnf - Social Science and the Humanities, Student's Book. (1) *suf*g pwef? ruf(wf)wD/ (2) Social Science and the Humanities, Student's Book. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en_US. Notes about usage: Organisations wishing to use the body text of this work to create a derivative work are requested to include a Mote Oo Education logo on the back cover of the derivative work if it is a printed work, on the home page of a web site if it is reproduced online, or on screen if it is in an app or software. For license types of individual pictures used in this work, please refer to Picture Acknowledgements at the back of the book. Social Science teachers from Myanmar's technological universities planning and preparing lessons with Social Science and the Humanities. -

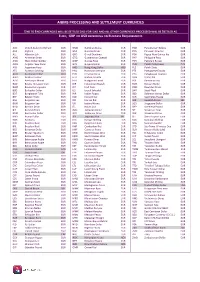

AIBMS Multicurrency List

AIBMS PROCESSING AND SETTLEMENT CURRENCIES END TO END CURRENCIES WILL BE SETTLED LIKE-FOR-LIKE AND ALL OTHER CURRENCIES PROCESSED WILL BE SETTLED AS EURO, GBP OR USD DEPENDING ON BUSINESS REQUIREMENTS AED United Arab Emi Dirham EUR GMD Gambian Dalasi EUR PAB Panamanian Balboa EUR AFA Afghani EUR GNF Guinean Franc EUR PEN Peruvian New Sol EUR ALL Albanian Lek EUR GRD Greek Drachma EUR PGK Papua New Guinea Kia EUR AMD Armenian Dram EUR GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal EUR PHP Philippine Peso EUR ANG West Indian Guilder EUR GWP Guinea Peso EUR PKR Pakistani Rupee EUR AON Angolan New Kwan EUR GYD Guyana Dollar EUR PLN Polish Zloty (new) PLN ARS Argentine Peso EUR HKD Hong Kong Dollar HKD PLZ Polish Zloty EUR ATS Austrian Schilling EUR HNL Honduran Lempira EUR PTE Portuguese Escudo EUR AUD Australian Dollar AUD HRK Croatian Kuna EUR PYG Paraguayan Guarani EUR AWG Aruban Guilder EUR HTG Haitian Gourde EUR QAR Qatar Rial EUR AZM Azerbaijan Manat EUR HUF Hungarian Forint EUR ROL Romanian Leu EUR BAD Bosnia-Herzogovinian EUR IDR Indonesian Rupiah EUR RUB Russian Ruble EUR BAM Bosnia Herzegovina EUR IEP Irish Punt EUR RWF Rwandan Franc EUR BBD Barbados Dollar EUR ILS Israeli Scheckel EUR SAR Saudi Riyal EUR BDT Bangladesh Taka EUR INR Indian Rupee EUR SBD Solomon Islands Dollar EUR BEF Belgian Franc EUR IQD Iraqui Dinar EUR SCR Seychelles Rupee EUR BGL Bulgarian Lev EUR IRR Iranian Rial EUR SEK Swedish Krona SEK BGN Bulgarian Lev EUR ISK Iceland Krona EUR SGD Singapore Dollar EUR BHD Bahrain Dinar EUR ITL Italian Lira EUR SHP St.Helena Pound EUR BIF Burundi -

Afford Two, Eat One. Financial Inclusion in Rural Myanmar

Afford TWO, Eat ONE Financial Inclusion in Rural Myanmar 1 2 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................4 Myanmar: Past & Present ...........................................................................................................................................6 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................................12 Archetypes .....................................................................................................................................................................30 Diversity of the Financial Landscape .......................................................................................................................60 Insights & Findings ..............................................................................................................76 Case Study: Monastery Lending Group ..............................................................................................................90 Case Study: Novitiate Ordination Ceremony .....................................................................................................146 Case Study: The Betel Business .............................................................................................................................168 Looking Ahead ..............................................................................................................................................................180 -

Report Name:Impact of Burma Military Coup on Agriculture Sector and Trade

Voluntary Report – Voluntary - Public Distribution Date: March 05, 2021 Report Number: BM2021-0009 Report Name: Impact of Burma Military Coup on Agriculture Sector and Trade Country: Burma - Union of Post: Rangoon Report Category: Agricultural Situation, Detained Shipments, Grain and Feed, Livestock and Products, Oilseeds and Products, Potatoes and Potato Products Prepared By: FAS Rangoon Approved By: Lisa Ahramjian Report Highlights: Since Burma initiated a series of political and economic reforms in 2011, U.S. agricultural exports have grown over 80-fold, reaching a record $174 million in 2019 and $167 million in 2020. However, the February 1, 2021 coup d'état and country-wide peaceful protests in opposition to the military’s actions, and the military’s increasingly violent response, have crippled the logistics sector and led to closures and delays in the trade and banking sectors. Collectively, this creates vast uncertainties for U.S. agricultural exports to Burma. THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY On February 1, 2021, Burmese State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, leader of Burma’s ruling party, and Burmese President Win Myint, the duly elected head of government, were deposed in a military coup d'état. The military dismissed Parliament, instead created the State Administrative Council, and announced new Union Ministers starting on February 1. The military regime declared a one-year state of emergency after which it pledges to hold elections. It is widely believed that the military regime will not hold elections at that time. The United States, the United Nations, and like-minded countries have condemned the coup and the military’s use of violence in suppressing protests. -

Myanmar Kyat Current Account Terms and Conditions

Myanmar Kyat Current Account Terms and Conditions These are the Terms and Conditions applicable to Kanbawza Bank Limited’s (KBZ Bank) Myanmar Kyat Current Account: 1. Definitions ‘Customer’ refers to a KBZ Bank customer holding the Myanmar Kyat Current Account. ‘Account’ refers to the Myanmar Kyat Current Account. ‘Cheque’ refers to a bill of exchange drawn on the Bank by the Customer. ‘Introducer’ refers to a person who already holds a Myanmar Kyat Current Account that acts as a referee for new customers. ‘Myanmar Kyat’ refers to the official currency of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar. ‘Schedule of Fees’ refers to the list of fees collected by the Bank that may change from time to time at the Bank’s discretion. ‘Website’ refers to the KBZ Bank Website at www.kbzbank.com 2. Opening of an Account with KBZ Bank a) The Customer is required to complete all relevant application forms provided by the Bank and must provide all relevant documents in order to open an account with KBZ Bank. b) The Customer must be the legal age of 18 and possess the competency to enter into contracts to open an account. c) The Customer must be referred by two introducers at the KBZ branch when opening an account. d) All the account/s held by the name of an individual shall be operated solely by the individual. Account/s held by the name of a company shall be operated by the designated person/s approved by such company and evidenced by a letter approving such designation. e) An initial deposit of not less than 10,000 Myanmar Kyats must be deposited into the Account/s. -

The Evolution and Impact of Asian Exchange Rate Regimes

ADB Economics Working Paper Series The Evolution and Impact of Asian Exchange Rate Regimes Ramkishen S. Rajan No. 208 | July 2010 ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 208 The Evolution and Impact of Asian Exchange Rate Regimes Ramkishen S. Rajan July 2010 (Revised: 14 January 2011) Ramkishen S. Rajan is Associate Professor in the School of Public Policy, George Mason University. This paper was initially prepared as a background material for the Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) Asian Development Outlook 2010 (www.adb.org/Economics/). The paper draws on and builds upon joint work by the author with Tony Cavoli and Victor Pontines. Excellent research assistance by Sasidaran Gopalan is also gratefully acknowledged. The usual disclaimer applies. Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org/economics ©2010 by Asian Development Bank July 2010 ISSN 1655-5252 Publication Stock No. WPS102896 The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Asian Development Bank. The ADB Economics Working Paper Series is a forum for stimulating discussion and eliciting feedback on ongoing and recently completed research and policy studies undertaken by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) staff, consultants, or resource persons. The series deals with key economic and development problems, particularly those facing the Asia and Pacific region; as well as conceptual, analytical, or methodological issues relating to project/program economic analysis, and statistical data and measurement. The series aims to enhance the knowledge on Asia’s development and policy challenges; strengthen analytical rigor and quality of ADB’s country partnership strategies, and its subregional and country operations; and improve the quality and availability of statistical data and development indicators for monitoring development effectiveness. -

Report Name: Rice Trade - Monthly

Required Report: Required - Public Distribution Date: February 19,2021 Report Number: BM2021-0004 Report Name: Rice Trade - Monthly Country: Burma - Union of Post: Rangoon Report Category: Grain and Feed Prepared By: Approved By: Lisa Ahramjian Report Highlights: In January 2021, Burma’s rice exports are forecast to decrease overall due to high domestic prices and since the Chinese government has not yet issued 2021 import permits for head rice. However, broken rice exports to China increased due to high demand before the Chinese New Year. Domestic prices for Emata 25 percent broken rice increased due to potential exports to Bangladesh and Malaysia while the prices for superior quality Shwe Bo Pawsan rice remain unchanged. Burma’s rice exports in February are forecast to be weak due to the country-wide Civil Disobedience Movement following the February 1, 2021 coup, in which the military overthrew the democratically elected civilian government. THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Production: Burma plans to grow approximately 6.1 million hectares (MHa) of the main rice crop (monsoon rice) and 1 MHa of the second crop in 2020/21. As of the end of January 2021, 99 percent of the main rice crop was harvested and 45 percent of the second crop was planted. Yields from the main 2020/21 rice crop are lower than anticipated due to the lack of sufficient water and unusual rain during harvest time. Under Burma’s COVID-19 Economic Relief Plan (CERP), the government spent more than 14 billion Myanmar Kyats (US $10.5 million) to support 100,000 acres of rice seed production.