Viśvarūpa – Book by Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rule Breaches in NUS Referendum Spark Controversy

!ZPSLOPVTFt ZPSLOPVTFt @yorknouse twww.nouse.co.uk Meet the Ready for the Ball? new socs Get inspired for the Summer Ball with The Shoot M.10 From drones to Game of Thrones M.4 Shortlisted for Guardian Student Publication of the Year 2015 Est. 1964 Sponsored by Nouse Tuesday 07 June 2016 Rule breaches in NUS Referendum spark controversy The NUS has come under fire for 3rd party campaigning student members.” Amy Gibbons and Ben Rowden Campaigners on both sides DEP EDITOR AND NEWS EDITOR have taken starkly opposing views on the matter, with ambiguity about whether the email counted as ‘third party campaigning’ proving a con- THE NATIONAL UNION of Stu- tentious issue. Such ambiguity has dents has been accused of unau- left questions open as to how clearly thorised third party campaigning rules have been established between in the NUS Referendum at York stakeholders in the campaign. following an email that was sent out Lucas North, on behalf of ‘York to NUS Extra customers last week, Says Yes to NUS’, told Nouse: “‘Yes urging them to vote Remain. to NUS’ do not consider the email The email, which was sent on sent to students a breach of the Wednesday, listed eight reasons campaign rules, this is because they why customers should vote to re- are an external party who are not main in the NUS, in addition to the bound by the rules, and students benefits assumed from owning an who received it opted in to receiving NUS Extra card. communication from NUS Extra. It read: “NUS is more than just “To my understanding, person- a discount card, it is an organisation ally, both the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ cam- dedicated to making a better life for paigns were made aware of the cam- all students [...] Make sure you vote paign rules. -

CEU Department of Medieval Studies

ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU VOL. 18 2012 Central European University Budapest Annualis 2012.indb 1 2012.07.31. 15:59:40 Annualis 2012.indb 2 2012.07.31. 15:59:42 ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU VOL. 18 2012 Edited by Judith Rasson and Marianne Sághy Central European University Budapest Department of Medieval Studies Annualis 2012.indb Sec1:1 2012.07.31. 15:59:42 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the permission of the publisher. Editorial Board Niels Gaul, Gerhard Jaritz, György Geréby, Gábor Klaniczay, József Laszlovszky, Marianne Sághy, Katalin Szende Editors Judith Rasson and Marianne Sághy Technical Advisor Annabella Pál Cover Illustration Labskhaldi Gospel, 12th century, 29×22 cm, parchment. Canon Table, detail (4 r) Georgian National Museum. Svanety Museum of History and Ethnography, Mestia. www.museum.ge. Reproduced by permission Department of Medieval Studies Central European University H-1051 Budapest, Nádor u. 9., Hungary Postal address: H-1245 Budapest 5, P.O. Box 1082 E-mail: [email protected] Net: http://medievalstudies.ceu.hu Copies can be ordered at the Department, and from the CEU Press http://www.ceupress.com/order.html ISSN 1219-0616 Non-discrimination policy: CEU does not discriminate on the basis of—including, but not limited to—race, color, national or ethnic origin, religion, gender or sexual orientation in administering its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other school-administered programs. © Central European University Produced by Archaeolingua Foundation & Publishing House Annualis 2012.indb Sec1:2 2012.07.31. -

Spawn Origins: Book 4 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SPAWN ORIGINS: BOOK 4 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Todd McFarlane,Alan Moore | 325 pages | 27 Sep 2011 | Image Comics | 9781607064374 | English | Fullerton, United States Spawn Origins: Book 4 PDF Book Spawn Origins TPB 1 - 10 of 20 books. Dissonance Volume 1. I love seeing Malebolgia and listening to Count Cogliostro. Includes the classic "Christmas" issue as well as the double-sized issue 50! Revisit stories of deception and betrayal,with Al's former boss, Jason Wynn, in the center of it all. Jun 08, Julian rated it it was ok Shelves: comic-books , spawn. Average rating 3. I was aware of Neil Gaiman's legal battles over Angela, Cogliostro and Medieval Spawn but I had no idea the extent to which later issues would continually refer back to ideas which were outsourced. View basket. Showing I dunno they don't tell you much and it's a odd place to start. Another darn good volume of Spawn. Spawn: Origins, Volume 9. United Kingdom. And for years, the passengers and crew of the vessel Orpheus found the endless void between realities to be a surprisingly peaceful home. Spawn: Hell On Earth. Then the last one is kind of a weird one about Spawn seeing a different outlook on things and maybe not being a complete dick to everyone he meets all the time. Anyway next 4 issues begin the "Hunt" which has basically put Terry, Spawn's friend, in the middle of a all out war and everyone wants him done. Brit, Volume 1: Old Soldier. Seller Inventory ADI The guest writers on the early Spawn titles Moore, Morrison and Gaiman really hit it out of the park by establishing interesting lore that had implications for the whole Spawn universe. -

Club Add Form

O GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: EARTH O CAPTAIN TRIPS PREMIERE HC SHALL OVERCOME PREMIERE HC Collects Collecting THE STAND: CAPTAIN TRIPS #1-5. MARVEL SUPER-HEROES #18, MARVEL TWO-IN- 160 PGS...$24.99 ONE #4-5, GIANT-SIZE DEFENDERS #5 and DE- O MARVEL MASTERWORKS: FANTASTIC FENDERS #26-29.176 PGS./Rated A ...$19.99 FOUR VOL. 1 TPB Collecting THE FANTASTIC O MARVEL ADVENTURES THE AVENGERS STAR WARS ADVENTURES VOL.1 Digest on-going FOUR #1-10. 272 PGS...$24.99 VOL. 8: THE NEW RECRUITS DIGEST O MARVEL MASTERWORKS: GOLDEN AGE Collecting MARVEL ADVENTURES THE AVEN- Before they ever met Luke Skywalker or Princess Leia, Han Solo and Chewbacca had MARVEL COMICS VOL. 4 HC Collecting MARVEL GERS #28-31. 96 PGS./All Ages ...$9.99 already lived a lifetime of adventures. In this action-packed tale, Han and Chewie are MYSTERY COMICS #13-16. O SKRULLS VS. POWER PACK DIGEST caught between gangsters and the Empire, and their only help is Han's former partner- 280 PGS ...$59.99 Collecting SKRULLS VS. POWER PACK #1-4 O MARVEL MASTERWORKS: THE INCREDI- 96 PGS./All Ages ...$9.99 -who may be worse than either! This is a new series of GNs designed for of all ages! BLE HULK VOL. 5 HCCollecting THE INCREDIBLE O MINI MARVELS: SECRET INVASION DIGEST HULK #111-121.240 PGS..$54.99 96 PGS./All Ages ...$9.99 SOUL KISS #1 (of 5) O WOLVERINE OMNIBUS VOL. 1 HC Collecting O SECRET INVASION: FRONT LINE TPB $14.99 STEVEN T. SEAGLE comes to Image for SOUL KISS - the story of a woman with MARVEL COMICS PRESENTS #1-10, #72-84; IN- O SECRET INVASION: BLACK PANTHER $12.99 vengeance on her mind and damnation on her lips. -

United States District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF WISCONSIN NEIL GAIMAN, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Case No. 02-CV-00048-bcc TODD McFARLANE, et al., Defendants. THE McFARLANE DEFENDANTS’ BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR ORDER DECLARING GAIMAN’S INTEREST IN CERTAIN COMIC BOOK CHARACTERS Defendants Todd McFarlane and Todd McFarlane Productions, Inc. (together, the “McFarlane Defendants”) submit this brief in opposition to plaintiff Gaiman’s motion for an order declaring that he has a copyright interest in the following three comic book characters: Dark Ages Spawn, Tiffany and Domina (the “Pending Accounting Motion”). INTRODUCTION As more fully discussed below, there are three distinct and fully sufficient grounds on which to deny the Pending Accounting Motion: 1. Mr. Gaiman is improperly attempting, through a post-judgment accounting procedure, to expand the judgment in this action to grant him an ownership interest in three additional copyrights despite having never asserted any such claim in the lawsuit. In particular, the three characters at issue in his motion were never raised in any fashion whatsoever—or even mentioned—in his pleadings or at trial in this case. Now, after judgment, Mr. Gaiman seeks improperly to supplement the record with hand-selected images that are misleading in their appearance. Due process requires that any adjudication of these new claims concerning additional characters be one in which the evidence can be tested, authenticated and explained to a trier of fact. A quasi-administrative, post-judgment accounting procedure is not the proper time or place, and this Court should reject Mr. Gaiman’s effort to obtain by way of motion what he has never sought by way of trial. -

Cagliostro and His Egyptian Rite of Freemasonry

CAGLIOSTRO AND HIS EGYPTIAN RITE OF FREEMASONRY By HENRY RIDGELY EVANS, 'Litt.D., 33° Hon. Gra nd Tiler of the Supreme Council, A.'. A... S.·. R:. of Freemasonry for the Southern Jurisdiction of the United States. TOGETHEI! WITH A N EXPOSITION OF' THE FIRST DEGREE OF' THE EGYPTIAN RITE Translated from the French by HORACE PARKER McINT03R, 33° Hon. (Reprinted from the New Age Maga.zine.) WASHINGTON, D. C. 1919 COUNT CAGLIOSTRO CAGLIOSTRO AND HIS EGYPTIAN RITE OF FREEMASONRY~ INTRODUCTION "Unparalleled Cagliostro! Looking at thy so attractively decorated private theater, wherein thou aetedst and livedst, what hand but itches to draw aside thy curtain and, turning the whole inside out, find thee in the middle thereof ?"- CARLYU, : J\lJ isc ella.neo1ts Essays. N the Rue de Beaune, Paris, a few doors from the house where Voltaire died, is a shabby genteel little hostelry, dating back to pre-revolutionary I times; to the old regime of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. You ring the bell of the concierge's office, and the wrought-iron gates open with a clang. Mine host welcomes you at the portal and, with the airs and graces of an aristocrat of the eighteenth century, ushers you up to the state bedroom. Ah, that bedroom, so old and quaint, with its huge four-post bed, garnished with faded. red curtains and mounted upon a raised dais. The chimney-piece is carved and bears the half-obliterated escutcheon of the builder of the man ~ion-a noble of the old regime. Over the mantle hangs a large oval mirror set in a tarnished gilt frame. -

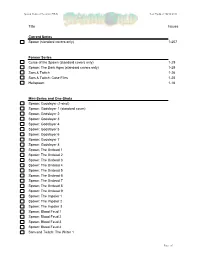

Spawn Comics Checklist (USA)

Spawn Comics Checklist (USA) Last Updated: 06/18/2011 Title Issues Current Series Spawn (standard covers only) 1-207 Former Series Curse of the Spawn (standard covers only) 1-29 Spawn: The Dark Ages (standard covers only) 1-28 Sam & Twitch 1-26 Sam & Twitch: Case Files 1-25 Hellspawn 1-16 Mini-Series and One-Shots Spawn: Godslayer (1-shot) Spawn: Godslayer 1 (standard cover) Spawn: Godslayer 2 Spawn: Godslayer 3 Spawn: Godslayer 4 Spawn: Godslayer 5 Spawn: Godslayer 6 Spawn: Godslayer 7 Spawn: Godslayer 8 Spawn: The Undead 1 Spawn: The Undead 2 Spawn: The Undead 3 Spawn: The Undead 4 Spawn: The Undead 5 Spawn: The Undead 6 Spawn: The Undead 7 Spawn: The Undead 8 Spawn: The Undead 9 Spawn: The Impaler 1 Spawn: The Impaler 2 Spawn: The Impaler 3 Spawn: Blood Feud 1 Spawn: Blood Feud 2 Spawn: Blood Feud 3 Spawn: Blood Feud 4 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 1 Page of Spawn Comics Checklist (USA) Last Updated: 06/18/2011 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 2 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 3 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 4 Angela 1 Angela 2 Angela 3 Cy-Gor 1 Cy-Gor 2 Cy-Gor 3 Cy-Gor 4 Cy-Gor 5 Cy-Gor 6 Violator 1 Violator 2 Violator 3 Spawn: Blood & Shadows (Annual 1) Spawn Bible (1st Print) Spawn Bible (2nd Print) Spawn Bible (3rd Print) Spawn: Book of Souls Spawn: Blood & Salvation Spawn: Simony Spawn: Architects of Fear The Adventures of Spawn Director’s Cut The Adventures of Spawn 2 Celestine 1 (green) Celestine 1 (purple) Celestine 2 Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) vol1 (1st Print) Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) vol1 (2nd Print) Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) -

Image United Image United Marca Un Cambio Muy Grande En La Ma- Finales

inter medios Medios Urbanos HÉROES LA RED de tinta de la web (Por Daniel Pizarro) (Por Urbana) El cómic se dibujó de una E-mail: [email protected] forma muy particular. E-mail: [email protected] Image United Image United marca un cambio muy grande en la ma- finales. Una manera poco ortodoxa de trabajar, pero nera de crear crossovers en el mundo del cómic, ya que visualmente debe ser impresionante. que aunque hemos leído otras historias que juntan a La historia nos presenta a Fortress, personaje todos los personajes de una compañía (sobre todo en creado por Portacio, un hombre normal atrapado en este año), esta es la única que puede presumir de tener un traje del que no puede salir que le otorga poderes tanto talento en cada página. Con un guión de Robert que no sabe controlar, quien empieza a tener visiones Kirkman (Invincible) y el dibujo de de una guerra próxima donde todos los casi todos los miembros fundadores héroes del Universo Image son derro- Bienvenidos a la de Image: Erik Larsen, Todd McFarla- tados. Esto hace que nuestro protago- ne, Marc Silvestri, Rob Liefeld, Whilce nista se lance a reunir a los personajes falsa ubicuidad Portacio y Jim Valentino (faltando Jim principales de la compañía (Savage Lee, por obligaciones contractuales Dragon, Spawn, Shadowhawk, Witchbla- Todos los fans y curiosos que entraron a YouTube el domingo con DC), Image United promete ser de, entre otros) para poder hacer frente 25 de octubre por la noche pudieron ver (y no todos disfrutar) uno de los grandes eventos de lo que a la amenaza llamada Dark Spawn, que un concierto en vivo de U2. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

SEP09 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 8/13/2009 2:03 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 12SEP 2009 SEP E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG COF C2:Layout 1 8/12/2009 10:32 AM Page 1 COF Gem Page Sept:gem page v18n1.qxd 8/13/2009 2:11 PM Page 1 AGE OF REPTILES: THE JOURNEY #1 DR. HORRIBLE ONE-SHOT DARK HORSE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN/DOC SAVAGE SPECIAL #1 DC COMICS BLACKEST NIGHT #5 DC COMICS IMAGE UNITED #1 IMAGE COMICS MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH DARK X-MEN #1 MARVEL COMICS PILOT SEASON: MURDERER WIZARD MAGAZINE #218 IMAGE COMICS WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT COF FI Page Sep:COF FI Page December.qxd 8/13/2009 2:13 PM Page 1 featuredfeatured itemsitems PREMIER (GEMS) TOYS & MODELS Dr. Horrible G Dark Horse Comics Voltron 25th-Anniversary Metallic Lion Gift Set G Age of Reptiles: Journey #1 G Dark Horse Comics Animation Blackest Night #5 G DC Comics Thundercats: Lion-O Statue G Cartoons Batman/Doc Savage Special G DC Comics The Maestro Statue G Marvel Heroes Image United #1 G Image Comics Pilot Season: Murderer #1 G Image Comics DESIGNER TOYS /Top Cow Productions Dark X-Men #1 G Marvel Comics Bunk Bots Plushes G Designer Toys Wizard Magazine #218 G Wizard Entertainment Hello Kitty mimoBot 4-Gigabyte USB Flash Drives G Designer Toys COMICS Sweet Meat Plushes G Designer Toys SuperGod #1 G Avatar Press IMPORT TOYS & MODELS Female Force: Stephenie Meyer G Bluewater Productions Marvel Comics: Scarlet Witch Bishoujo Statue G Farscape Ongoing #1 G BOOM! Studios Kotobukiya The World of Cars: Radiator Springs TP G BOOM! Terminator 2: T-800 Endoskeleton Die-Cast Figures G Studios -

Holy Fandom, Batman! Commercial Fan Works, Fair Use, and the Economics of Complements and Market Failure

THIS VERSION DOES NOT CONTAIN PAGE NUMBERS. PLEASE CONSULT THE PRINT OR ONLINE DATABASE VERSIONS FOR PROPER CITATION INFORMATION. NOTE HOLY FANDOM, BATMAN! COMMERCIAL FAN WORKS, FAIR USE, AND THE ECONOMICS OF COMPLEMENTS AND MARKET FAILURE Christina Chung* INTRODUCTION The average American spent $2,504 on media and entertainment in 2010.1 In addition to spending money, the average American spends about 2.7 hours per day watching television—and countless hours more reading, playing video games, and engaging in other forms of entertainment.2 Given the significant time and money that Americans spend on entertainment, it should come as no surprise that popular culture constitutes a major component of modern American life. For many consumers, passively engaging in entertainment— watching television, reading books, listening to music—is sufficient. Other consumers feel compelled to discuss their reactions to media with other entertainment consumers, whether they do so in person with friends and family, or online through message boards and forums.3 For many entertainment consumers, however, simply experiencing and discussing popular culture works is unsatisfactory. This particular subset of consumers known as fans—a term derived from the term “fanatic”4—often feels such an affinity to popular culture works that they respond to them with their own creative expression.5 The product of this expression can manifest in a wide variety of forms, including literary works such as fan fiction, audiovisual works such as fan videos, and pictorial works such as fan art.6 * J.D. 2013, Boston University School of Law; B.A. English 2010, Cornell University. I would like to thank Professor Wendy Gordon for serving as a spirit guide in the crazy mixed up world of copyright, Jen Neubauer for her keen editing and guidance, and Eric Auerbach for his love of economics—without them, this note would not have been possible. -

07/30/2010 Page 1 of 14

Case: 3:02-cv-00048-bbc Document #: 323 Filed: 07/30/2010 Page 1 of 14 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF WISCONSIN - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - NEIL GAIMAN, OPINION AND ORDER Plaintiff, 02-cv-48-bbc v. TODD McFARLANE, TODD McFARLANE PRODUCTIONS, INC., and TMP INTERNATIONAL, INC., Defendants. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - This long-running copyright case is almost at a close. The one remaining matter for the court’s determination is plaintiff Neil Gaiman’s motion to compel defendants to turn over all documents in their possession relating to income attributable to three characters known as Domina, Tiffany and Dark Ages Spawn, featured in a series of comics written and published by defendants Todd McFarlane, McFarlane Productions and TMP International, Inc. The issue in dispute is whether the three characters are derivative of two characters known as Angela and Medieval Spawn that are subject to the parties’ joint copyright interest. The parties agree that they are co-owners of Angela and Medieval Spawn. Defendants 1 Case: 3:02-cv-00048-bbc Document #: 323 Filed: 07/30/2010 Page 2 of 14 do not contest plaintiff’s right to an accounting and division of profits for the posters, trading cards, clothing, statuettes, animated series on HBO, video games, etc. that feature those characters. The dispute is limited to information about the profits earned from Dark Ages Spawn, Tiffany and Domina, which defendant has refused to provide to plaintiff. Defendants contend that these characters are not subject to plaintiff’s copyright because they were based solely on plaintiff’s ideas and not on any physical expression of those ideas. -

(35045 Plymouth Road, Livonia MI 48150) Or Live Online Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook and Twitter @Back2past for Updates

2/27 - Holly Collection Comic Books, Part One 2/27/2019 This session will be held at 6PM, so join us in the showroom (35045 Plymouth Road, Livonia MI 48150) or live online via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! (Showroom Terms: No buyer's premium! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast (See site for terms) LOT # LOT # 1 Auctioneer Announcements 17 Amazing Spider-Man #602/Pin-Up Cover A short address from auctioneer emeritus Andy Cirinesi. NM condition. 2 Amazing Spider-Man #363 CGC 9.8/Key 18 Amazing Spider-Man #553/Classic Cover 3rd appearance of Carnage. CGC graded comic. NM condition. 3 Amazing Spiderman #299/Key Issue 19 Amazing Spider-Man #543/Classic Cover 1st brief appearance of Venom in NM condition. NM condition. 4 Incredible Hulk #181/Marvel Milestone ED 20 Amazing Spider-Man #540-541 Lot of (2) NM condition. NM condition. 5 Image United #1/2009/Variant Spawn "C" 21 Amazing Spider-Man #497/Classic Cover NM condition. NM condition. 6 Incredible Hulk #34/2002/Key Issue 22 Amazing Spider-Man #496/Classic Cover NM condition. NM condition. 7 Alias #4/2002/Bendis 23 Amazing Spider-Man #495/Dodson Cover NM condition. NM condition. 8 Deadpool #51/2001/Detective Cover Swipe 24 Amazing Spider-Man #489/Cho Cover NM condition. NM condition. 9 Superman #204/2004/1st Jim Lee 25 Amazing Spider-Man #491/Campbell Cover Sharp VF/VF+ condition.