Student Life at Dalhousie University in the 1930S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December of J, Ici4g

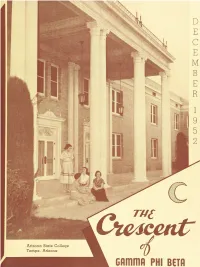

TU� Oie^cetvt Arizona State College Tempe, Arizona Gflmmfl PHI BETfl K^med of Ljamma J^kl (ISeta Gamma Phi Beta from the past has given A heritage that makes a fuller life. Gamma Phi Beta in the present bids Us strive for lasting values and ideals. Gamma Phi Beta in the days to come Will prove that fundamentals can endure. Therefore we shall embody in our lives The truths that make for finer womanhood. Once more we pledged a loyahy that means Adherence to all true and noble things; A learning that enriches all our days With magic gold that is forever ours ; A labor that each hour will glorify The simple, common task, the common cause; A love that will be strong and great enough To compass and to pity all the world. tJLove, c=Labor, <JLearnlna, cLouatlij� KJnr L^reed I ivill try this day tO' live a simple, sincere and serene life, re pelling promptly every thought of discontent, anxiety, dis couragement, impurity, self-seeking; cultivating cheerfulness, magnanimity, charity and the habit of holy silence; exercising economy in expenditure, generosity in giving, carefulness in conversation, diligence in appointed service, fidelity to every trust and a childlike faith in God. The Crescent of Gamma Phi Beta Voliune LII^ Numbear 4 The Cover West Hall, women's dormitory at Arizona State College, Tempe, Arizona where Beta Kappa chapter Gamma Phi Beta was chartered December of j, ici4g. Another Link Is Added, Frontispiece 2 The Crescent is published September 15, Decem ber I, March 15, and May 1, by the George Banta Let's Visit Arizona State College 3 Publishing Company, official printers of the fraternity, at 450 Ahnaip Street, Menasha, Wiscon Harriet Shannon Lee Promoted to Lieutenant Colonel .. -

Letter from Christian Chan, Alumnus, Phi Kappa Pi

C. Chan ITEM LS 25.2 - Review of Fraternity and Sorority Houses Exemption to Chapter 285,LS25.2.3 Rooming Houses May 2, 2018 From: Christian Chan To: Councillors and Members of the City of Toronto Licensing and Standards Committee Via Email Re: ITEM LS 25.2 - Review of Fraternity and Sorority Houses Exemption to Chapter 285, Rooming Houses Dear Councillors and Members of the Municipal Licensing Standards Committee, I introduce myself to you as the outgoing chief executive of the governing council of my Fraternity, Phi Kappa Pi. Phi Kappa Pi is Canada’s Oldest and Only National Fraternity, with active Chapters in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver. I am also a long time Annex resident, and grew up in the neighbourhood. I have served as a Director on the Board of Directors of the Annex Resident’s Association while I was in planning school and while living at my Fraternity house during undergraduate studies. Now I practice as a Land Use Planner and I am a former Member and Chair of the Toronto and East York Committee of Adjustment. I still live in the Annex, and I can subjectively say and with great bias that it is the best neighbourhood in the world. Below I would like to respectfully submit to the Committee the following comments with regards to the above-referenced Item before the Licensing and Standards Committee on May 4, 2018: 1. Rooming Houses and Fraternity/Sorority Houses Materially Different: Rooming Houses In June 2015 the City issued a Request for Proposal for Rooming House Review Public consultations (Request for Proposal No. -

Dr. Victoria A. Stuart, Ph.D. Curriculum Vitae

Dr. Victoria A. Stuart, Ph.D. Curriculum vitae Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada (604) 628-9609 [email protected] Persagen.com Current Scientific Consultant j Owner: Persagen.com Jun 2009 - Present Position I have been self-employed since June 2009 as a Scientific Consultant, providing scientific expertise in molecular genetics, genomics, molecular biology, life sciences, bioinformatics and scientific review. Recent From 2009-2014 I was subcontracted to Battelle Memorial Institute (Chapel Hill, N.C.), pro- Work viding scientific expertise for the U.S. Army Research Office (ARO; Durham, N.C.) and the U.S. Army Center for Environmental Health Research (USACEHR; Washington, D.C.). That work primarily involved evaluation of molecular genetics and other life sciences research pro- posals for the ARO, and analyses of genomic expression data (Yersinia pestis-infected primate cells) for the USACEHR. That work, with my previous postdoctoral studies, reinforced my desire to pursue a career in bioinformatics. From 2015–present I have been immersed in a highly concentrated self-supported and -directed programme of study to acquire the tools in core domains (data management; programming languages; informatics; graphical models; data visualization; natural language processing; machine learning) needed to realize my Vision. Consequently, I possess a theoretical un- derstanding and appreciation of the underlying principles (modeling; loss functions; gradient descent; back propagation; tensors; linear algebraic approaches such as eigenvalues and semir- ings applied to data matrices; etc.) associated with leading-edge machine learning and natural language processing models. I am presently concentrating on the use of established, yet high performing approaches to re- lation extraction (e.g. -

Local Talent Hopes to Save Wolves

HAPPY VALENT NE' NEWS --. Ovide Mercredi visits Dal, p.S. ARTS --. Gwen Noah's last show, p. 8. SPORTS --. Two wrestlers off to CIAUs, p.12. - • . I Vol. 128, No. 18 . .- D '"i SIE UNIVERSITY, HALIFAX, N.S. Thursday, February 15, 1996 Watts trial Local talent hopes to save wolves underway BY ANDREW SIMPSON tion raised at the CCW in its 21 public and private sectors are cause eludes Never Cry Wolf years of operation. to be optimistic that the wolves may Except for Fentress and Ryan, BY PATTI WALLER With sweeping cuts to university The CCW was informed by be saved from relocation. all were previously uninvolved research. students and professors Dalhousie that as of April 1, "There have been so many peo with the wolves and are volun The six men accused of the sav know it doesn't hurt to be study 19 9 6, the administration would ple interested in this .. and the in teering their time for free. age beating of Darren Watts went ing something furry and beautiful. cease to provide funding for the terest keeps picking up ... we hope "With the people we have on trial Feb. 5. nearly a year and When Dalhousie Psychology centre. The centre has, in the past, to keep building on the enthusi working for us now, we would be five months after the incident took Students aQ.d Professors (DAPS) received $25.000 per year from asm," said Fentress. broke in no time if we had to pay_ place. spread the word that funding for Dalhousie. The loss of that fund The CCW now has an unofficial them .. -

1 Students Claim Investigations 10

I FLIGHTS TO EUROPE 1 You and your immediate fa- chartering an aircraft from CPA B INDIA IN BUT PROMISING mily are eligible to participate for The per H in one of two separate travel passenger cost will be By Heather offered by Here is the suggested flight I India is in a transition period For per a for the I and can bo very success- group of 25 or more can take To I ful in the forthcoming years if q round trip flight to Europe Leave Winnipeg May 2763 I she is capable of handling the for three Our suggested Arrive London May 28 upcoming according flight schedule From of Mc-Gi- ll to Michael To Leave London July 9 HI Leave Winnipeg May 2763 Arrive Winnipeg July 9 speaking H Brocher was Arrive London May 28 Application forms are avail- - H on The First From able from Konny in the H of this Years' on the final day Leave London 21 Executive The H year's Commonwealth Arrive Winnipeg 21 deadline for the of H is considering applications is H In the political In- dia's first accomplishment was the integration of some Three Students Claim I varying in size from that of France to our university Investigations he These states I three to accede to Three he and Tommy Douglas will H to Pakistan or to assert University of British Columbia soon reveal the names of three H By 1951 the prob- students claim they know of students on other campuses who H bloodless have been investigated by the lem had vanished in a ROMP undercover I accomplished by a ions on the university military None of the professors With the accession and trans- During an investigation -

Table of Contents Stewart Howe Alumni Service, 1929

F26/20/30 Alumni Association Alumni Stewart S. Howe Collection, 1810- TABLE OF CONTENTS STEWART HOWE ALUMNI SERVICE, 1929-1972 ...............................6 BOOK LIST ................................................................13 Fraternity ............................................................13 Education ............................................................16 Higher Education ......................................................17 Colleges and Universities ................................................24 BUSINESS, 1905-1972 ........................................................39 CONTEMPORY POLITICAL & SOCIAL TRENDS, 1963-1972 ....................41 COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES, 1766-1997 ...................................45 FINDING AIDS, Undated .....................................................69 FRATERNITY AND SORORITY JOURNALS, PUBLICATIONS, AND FILES, 1810- Subseries FJ, FP, and F .................................................70 FRATERNITY PUBLICATIONS - RESTRICTED, 1927-1975 .....................178 FUND-RAISING, 1929-1972 ..................................................179 FRATERNITY SUBJECT FILE, 1888-1972 .....................................182 GENERAL FRATERNITY JOURNALS, 1913-1980 ..............................184 HISTORICAL, 1636-1972 ....................................................185 HIGHER EDUCATION, 1893-1972 ...........................................190 INTERFRATERNITY ORGANIZATIONS, 1895-1975, 1979-1994, 1998 ............192 ILLINOIS AND CHICAGO, 1837-1972 ........................................200 -

Undergraduate Scholarships and Awards

UNDERGRADUATE SCHOLARSHIPS AND AWARDS Table of Contents About This Calendar .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Published by ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Undergraduate Scholarships and Awards 2018–2019 .......................................................................................... 5 Contact Information – Scholarships and Student Aid Office ............................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Entrance Awards ................................................................................................................................... 6 Entrance Scholarships ................................................................................................................................... 6 Entrance Bursaries......................................................................................................................................... 6 Athletic Awards for Entering Students .......................................................................................................... 6 1.2. In-Course Awards ................................................................................................................................. -

Noteworthy Fall 2018.Indd

noteworthy Fall 2018 news from the university of toronto libraries IN THIS ISSUE Fall 2018 6 Dedicated Volunteers + Library Book Room = A Winning Combination [ 3 ] Taking Note [ 11 ] Richard Charles Lee Canada-Hong Kong Library Events [ 4 ] Fifteen Million and Counting: the 1481 Caxton Cicero [ 12 ] Cheng Yu Tung East Asian Library’s Highlights [ 5 ] Dedication of the Phi Kappa Pi, Sigma Pi Reading Room [ 13 ] Keep@Downsview Receives Outstanding Contribution Award [ 6 ] Information-Savvy Students Win Undergraduate Research Prizes [ 13 ] Healthy Indoors & Outside: Green Spaces & Mental Wellness Talk & Workshop [ 6 ] Robarts Library Book Room Volunteers Receive an Arbor Award [ 14 ] Bringing Virtual Worlds to Life at Gerstein + MADLab [ 7 ] Launch of the Chancellors’ Circle of Benefactors [ 15 ] Exhibitions & Events [ 8 ] Cookery, Forgery, Theory and Artistry: All at the Fisher Cover image: Dust jacket from the yellowback edition of Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797–1851). Published by G. Routledge and Sons, London. 1882. Part of the De Monstris exhibition. Details on page 15. Above: Library Book Room volunteers receive their Arbor Awards. Story on page 6. [ 2 ] TAKING NOTE noteworthy news from the university of toronto libraries WELCOME TO THE FALL 2018 a daunting task. Artificial intelligence, Chief Librarian issue of Noteworthy. Recently I travelled to guided by expert librarians and archivists, Larry P. Alford China to visit a university library and may be part of the solution. Editor deliver a speech. I have had occasion previ- Recently, Neil Romanosky, Associate Jimmy Vuong ously to tour the libraries of Chinese Chief Librarian for Science Research & academic institutions, and this time I was Information, convened a UTL AI Interest Designer Maureen Morin struck by the growth and change since my Group to explore what the AI era will mean last visit. -

New President Here June 1

UBC .ReportsRETURN POSTAGE GUARANTEED VOLUME 13, No. 7 VANCOUVER 8, B.C. ” DECEMBER, 1967 NEWPRESIDENT HERE JUNE 1 - TheUniversity of B.C.’s president- designate,Dr. F. Kenneth Hare, will take uphis newpost June 1,1968. Enrolment Mr. Justice Nathan T. Nemetz, chair- man ofthe Board of Governors of UBC, has announced that Dr.Hare Warning will assume his presidential office fol- lowing a briefholiday after relin- quishinghis present position as mas- ter ofBirkbeck College of the Uni- Issued versityof London. In the meantime,Dr. Hare will pay B.C.’s three public universities have twobrief visits to the UBCcampus. warned that enrolment [imitations may benecessary in 1968. BANQUET SPEECH Hewill arrive in Vancouver Jan. Dean Walter Gage, actingpresident 21 to address an annual banquet spon- of UBC, issued his warning statement sored bythe UBC Commerce Under- late in Octoberfollowing a meeting graduateSociety in association with of the Senate. theVancouver Board ofTrade on STATEMENT APPROVED Jan. 22 inthe Hotel Vancouver. About half of the 500 guests at the The Senate, andlater the Board of banquet will be businessand finan- Governors,approved thefollowing cial leaders; theothers will be stu- statement, whichwill appear inthe dents. 1968 UBCCalendar: This will beDr. Hare’s first oppor- “TheUniversity reserves theright tunityto address the businesscom- tolimit enrolment in 1968-69 and munity.He will speak on “Business thereafter if its facilities and resources andthe University.” areinadequate. It followstherefore On Jan. 25, Dr. Hare will attend the thatthe University may not be able openingof the Legislative Assembly to accept all candidates who meet the on the invitation of Premier W.A. -

The International Fraternity

A PETITION TO The International Fraternity OF DELTA SIGMA PI BY THE ZETA KAPPA PHI FRATERNITY OF THE Department of Commerce Dalhousie University HALIFAX, Nova Scotia November 24, 1930 A PFTITIOK TO "" TEE laTKRl^^TIOEil FRiTEiiXUTi C:^ -T'T/i 1 PHI FRATERlilTi OF TH?: DEPi.HTL;.EHT OF GCS�M?SGF Di-LEOUSI"^ �y-�--- K OYA SC 0 TI /. C M S-.Ti A . lULIF iX , , '^'t. ^,S�H ^M^ �-'�-'^^ '3 T^JTRiUCE: oTUDIEY GilvlPUS. UME AUH OBJECTS OF OUR, .LOCAL. The name of our looal is ZETA KAPPA PHI. ZETA KAPPA PHI was organized to oreat e a spirit of brotherhood and group interests; to i'urther the interests of the University and especially those of the Commeroe de partment thereof; and to foster good ethics and hi^o-h ideals in business. To DELTA SIGMA PI: We the undersigned students and members of the Department of Commeroe of Dalhousie University and members of Zeta Kappa Phi, local oommerce fraternity, realizing the ben efits to be derived from membership in an international or ganization which fosters the study of business as a profession, dp hereby petition, in accordance with an unanimous resolution adopted by Zeta Kappa Phi on April 9th, 1930, that we be granted a charter to establish a chapter of DELAT SIG-l^U PI on the campus of Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Sootia, Canada, And furthermore, we pledge ourselves to abide by all the rules, laws, regulations and adopted standards of DELTA SIGlvIA PI, now in effect or which shall hereafter be enacted, and to promote a furtherance of the high ideals of the Fraternity, should our petition be accepted and a charter granted. -

Court File No. CV-17-578761-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF

Court File No. CV-17-578761-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION UNDER SECTION 182 OF THE BUSINESS CORPORATIONS ACT(ONTARIO) R.S.O. 1990, c.B.16. AS AMENDED PHI KAPPA PI BUILDINGS, LIMITED Applicant (Moving Party) MOTION RECORD OF THE APPLICANT (EX PARTE MOTION FOR AN INTERIM ORDER WITH RESPECT TO A PLAN OF ARRANGEMENT) (RETURNABLE ON JULY 20, 2017) LERNERS LLP 130 Adelaide Street West Suite 2400 Toronto, ON M5H 3P5 Jason Squire LSUC#: 431830 Tel: 416.601.2369 Fax: 416.867.2404 Domenico Magisano LSUC#: 45725E Tel: 416.601.4121 Fax: 416.601.4123 Lawyers for the Applicant INDEX INDEX Tab Description Page No 1 Notice of Motion 1 2 Affidavit of Hugh Anson-Cartwright sworn July 11, 2017 4 Exhibits A Reasons for decision of Justice Grace dated March 9 29, 2011 B Buildings' Letters Patent dated October 21, 1920 18 C Buildings' By-Laws, Numbers One and Two 21 D Land Title Parcel Register 29 E Mr. Avey's report dated October 23, 2006 30 F Minutes of the shareholders meeting dated November 149 10, 2010 G Resolutions of the Directors dated March 22, 2017 154 3 Draft Interim Order 163 4 Blacklined comparison of Draft Interim Order and 186 Appendices to Commercial List Users' Committee Form of Model Interim Order TAB I Court File No.: CV-17-578761-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE - COMMERCIAL LIST IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION UNDER SECTION 182 OF THE BUSINESS CORPORATIONS ACT(ONTARIO) R.S.O. 1990, c.B.16, AS AMENDED PHI KAPPA PI BUILDINGS, LIMITED Applicant NOTICE OF MOTION (EX PARTE MOTION FOR AN INTERIM ORDER WITH RESPECT TO A PLAN OF ARRANGEMENT) (RETURNABLE JULY 20, 2017) The Applicant, Phi Kappa Pi Buildings, Limited, will make a motion without notice to a judge presiding over the Commercial List on July 20, 2017 at 9:30 a.m., or as soon after that time as the motion can be heard, at 330 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario. -

Harwood First Candidates in Race First Definite Announcement of Candidacy in the Forth Tfowifitm Coming AMS Elections to Be Held February 5 Was Made Yes VOL

Livingstone/ Harwood First Candidates In Race First definite announcement of candidacy in the forth TfoWifitm coming AMS elections to be held February 5 was made yes VOL. XXLX VANCOUVER, B.C., THURSDAY, JANUARY 16,1947. No. 35 terday by Grant Livingstone and Bob Harwood. Committee They will be candidates for the offices of president and treasurer, respectively, of the Alma Mater Society. Revises In a statement accompanyinaccompanyingg ' F0R TREASURER his candidacy Livingstone, presi Denying rumours that he would dent of the UBC branch of the run for president of the council, Canadian Legion, said, "Several Harwood, Junior Member of this Poll Laws representative students on the year's AMS, made this statement campus have expressed the wish President of the LSE will be to The Ubyssey. that I stand for the presidency of elected in future by the whole "I have been asked to comment student body rather than by Liter the Alma Mater Society. I deeply appreciate the honor of their con on recent rumours that I would ary and Scientific Executive mem follow the precedent established bers only, announced Joy Done fidence. IMPORTANT YEAR by previous Junior Members and gani, AMS secretary Tuesday. be a candidate for Student Presi He went on to say that the com AMS Election Committee made dent in the forthcoming AMS elec ing year will be a great and cri this decision Tuesday because it tions. tical one. It is, one in which a was felt that as the president voted large scale program of student ini "In my opinion, the administra on matters affecting all students, tion of student affairs, when so his previous election was not suf tiative, leadership and effort will many students are older than in ficiently representative.