Air in Straight Sinus After Closed Head Injury Surgery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middle Cranial Fossa Sphenoidal Region Dural Arteriovenous Fistulas: Anatomic and Treatment Considerations

ORIGINAL RESEARCH INTERVENTIONAL Middle Cranial Fossa Sphenoidal Region Dural Arteriovenous Fistulas: Anatomic and Treatment Considerations Z.-S. Shi, J. Ziegler, L. Feng, N.R. Gonzalez, S. Tateshima, R. Jahan, N.A. Martin, F. Vin˜uela, and G.R. Duckwiler ABSTRACT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: DAVFs rarely involve the sphenoid wings and middle cranial fossa. We characterize the angiographic findings, treatment, and outcome of DAVFs within the sphenoid wings. MATERIALS AND METHODS: We reviewed the clinical and radiologic data of 11 patients with DAVFs within the sphenoid wing that were treated with an endovascular or with a combined endovascular and surgical approach. RESULTS: Nine patients presented with ocular symptoms and 1 patient had a temporal parenchymal hematoma. Angiograms showed that 5 DAVFs were located on the lesser wing of sphenoid bone, whereas the other 6 were on the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. Multiple branches of the ICA and ECA supplied the lesions in 7 patients. Four patients had cortical venous reflux and 7 patients had varices. Eight patients were treated with transarterial embolization using liquid embolic agents, while 3 patients were treated with transvenous embo- lization with coils or in combination with Onyx. Surgical disconnection of the cortical veins was performed in 2 patients with incompletely occluded DAVFs. Anatomic cure was achieved in all patients. Eight patients had angiographic and clinical follow-up and none had recurrence of their lesions. CONCLUSIONS: DAVFs may occur within the dura of the sphenoid wings and may often have a presentation similar to cavernous sinus DAVFs, but because of potential associations with the cerebral venous system, may pose a risk for intracranial hemorrhage. -

CHAPTER 8 Face, Scalp, Skull, Cranial Cavity, and Orbit

228 CHAPTER 8 Face, Scalp, Skull, Cranial Cavity, and Orbit MUSCLES OF FACIAL EXPRESSION Dural Venous Sinuses Not in the Subendocranial Occipitofrontalis Space More About the Epicranial Aponeurosis and the Cerebral Veins Subcutaneous Layer of the Scalp Emissary Veins Orbicularis Oculi CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF EMISSARY VEINS Zygomaticus Major CAVERNOUS SINUS THROMBOSIS Orbicularis Oris Cranial Arachnoid and Pia Mentalis Vertebral Artery Within the Cranial Cavity Buccinator Internal Carotid Artery Within the Cranial Cavity Platysma Circle of Willis The Absence of Veins Accompanying the PAROTID GLAND Intracranial Parts of the Vertebral and Internal Carotid Arteries FACIAL ARTERY THE INTRACRANIAL PORTION OF THE TRANSVERSE FACIAL ARTERY TRIGEMINAL NERVE ( C.N. V) AND FACIAL VEIN MECKEL’S CAVE (CAVUM TRIGEMINALE) FACIAL NERVE ORBITAL CAVITY AND EYE EYELIDS Bony Orbit Conjunctival Sac Extraocular Fat and Fascia Eyelashes Anulus Tendineus and Compartmentalization of The Fibrous "Skeleton" of an Eyelid -- Composed the Superior Orbital Fissure of a Tarsus and an Orbital Septum Periorbita THE SKULL Muscles of the Oculomotor, Trochlear, and Development of the Neurocranium Abducens Somitomeres Cartilaginous Portion of the Neurocranium--the The Lateral, Superior, Inferior, and Medial Recti Cranial Base of the Eye Membranous Portion of the Neurocranium--Sides Superior Oblique and Top of the Braincase Levator Palpebrae Superioris SUTURAL FUSION, BOTH NORMAL AND OTHERWISE Inferior Oblique Development of the Face Actions and Functions of Extraocular Muscles Growth of Two Special Skull Structures--the Levator Palpebrae Superioris Mastoid Process and the Tympanic Bone Movements of the Eyeball Functions of the Recti and Obliques TEETH Ophthalmic Artery Ophthalmic Veins CRANIAL CAVITY Oculomotor Nerve – C.N. III Posterior Cranial Fossa CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS Middle Cranial Fossa Trochlear Nerve – C.N. -

Venous Infarct

24F with Down Syndrome, presents with confusion & left sided weakness. Krithika Srikanthan, MD Jeffrey Guzelian, MD Leo Wolansky, MD Image with annotations • Please include findings in captions ? Deep Cerebral Venous Thrombosis with Venous Infarct • Hyperattenuation of straight dural sinus (red arrow) • Hypoattenuation of right thalamus and surrounding basal ganglia (blue arrow) Inferior sagittal sinus Straight sinus Internal Cerebral Vein Vein of Galen Increased density of straight sinus, extending into the inferior sagittal sinus, vein of Galen, & internal cerebral veins Magnified view shows hypodense edema of splenium (yellow arrow) contrasted by relatively normal genus of corpus callosum (white arrow). Axial DWI demonstrates hyperintensity involving the right thalamus (blue arrow) • Postcontrast subtraction MRV demonstrates near complete occlusion of straight dural sinus (red arrow) • The superior sagittal sinus is patent (blue arrow) Cerebral Venous Thrombosis Dural Sinus Cortical Vein Thrombosis Thrombosis Deep (Subependymal) Cerebral Vein Thrombosis CT Findings Non-contrast CT – Early imaging findings often subtle – Hyperdense sinus (compare to carotid arteries) • Usually > 65 HU • Distinguish thrombus vs. hyperdense sinus from high hematocrit (HCT) – HU:HCT ratio in thrombus 1.9 ± 0.32 vs. 1.33 ± 0.12 in nonthrombus – ± hyperdense cortical veins ("cord" sign) – ± venous infarct (50%) • White matter edema • Cortical/subcortical hemorrhages common • Thalamus/basal ganglia edema (if straight sinus, vein of Galen, and/or internal cerebral vein occlusion) CT Findings • Contrast Enhanced CT – "Empty delta" sign (25-30%) • Enhancing dura surrounds nonenhancing thrombus – "Shaggy," enlarged/irregular veins (collateral channels) – gyral enhancement – prominent intramedullary veins • CTA/CTV – Filling defect (thrombus) in dural sinus • Caution: Acute clot can be hyperdense, obscured on CECT/CTV – Always include NECT for comparison Differential Diagnosis • Asymmetric anatomy: hypoplasia or atresia of the transverse sinus. -

Human and Nonhuman Primate Meninges Harbor Lymphatic Vessels

SHORT REPORT Human and nonhuman primate meninges harbor lymphatic vessels that can be visualized noninvasively by MRI Martina Absinta1†, Seung-Kwon Ha1†, Govind Nair1, Pascal Sati1, Nicholas J Luciano1, Maryknoll Palisoc2, Antoine Louveau3, Kareem A Zaghloul4, Stefania Pittaluga2, Jonathan Kipnis3, Daniel S Reich1* 1Translational Neuroradiology Section, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, United States; 2Hematopathology Section, Laboratory of Pathology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, United States; 3Center for Brain Immunology and Glia, Department of Neuroscience, School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, United States; 4Surgical Neurology Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, United States Abstract Here, we report the existence of meningeal lymphatic vessels in human and nonhuman primates (common marmoset monkeys) and the feasibility of noninvasively imaging and mapping them in vivo with high-resolution, clinical MRI. On T2-FLAIR and T1-weighted black-blood imaging, lymphatic vessels enhance with gadobutrol, a gadolinium-based contrast agent with high propensity to extravasate across a permeable capillary endothelial barrier, but not with gadofosveset, a blood-pool contrast agent. The topography of these vessels, running alongside dural venous sinuses, recapitulates the meningeal lymphatic system of rodents. In primates, *For correspondence: meningeal -

A Study of the Junction Between the Straight Sinus and the Great Cerebral Vein*

J. Anat. (1989), 164, pp. 49-54 49 With 4 figures Printed in Great Britain A study of the junction between the straight sinus and the great cerebral vein* W. M. GHALI, M. F. M. RAFLA, E. Y. EKLADIOUS AND K. A. IBRAHIM Anatomy Department, Faculty of Medicine, Ain-Shams University, Cairo, Egypt (Accepted 10 August 1988) INTRODUCTION The presence of a small body projecting into the floor of the straight sinus at its junction with the great cerebral vein, and the nature of such a body have been the subject of controversy. Clark (1940) named it the suprapineal arachnoid body and described it as being formed of arachnoid granulation tissue filled with a sinusoidal plexus of blood vessels. He claimed that this body seemed to provide a ball valve mechanism whereby the venous return from the third and lateral ventricles might be impeded and this, in turn, would exert a direct effect on the secretion of the cerebrospinal fluid. Similar observations have been mentioned by Williams & Warwick (1980). On the other hand, Balo (1950) denied the role played by that body in the regulation of secretion of the cerebrospinal fluid. Thus the aim of the present work was to verify the presence of such a body and to investigate its nature and the possible role it might play in haemodynamic regulation in that strategic area. MATERIAL AND METHODS Twenty brains (15 from the dissecting room and 5 from the postmortem room of Ain-Shams University, Faculty of Medicine) were used for this study. They were of both sexes (12 males and 8 females) and their ages ranged from 40-60 years. -

The Five Diaphragms in Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine: Neurological Relationships, Part 1

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.8697 The Five Diaphragms in Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine: Neurological Relationships, Part 1 Bruno Bordoni 1 1. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Foundation Don Carlo Gnocchi, Milan, ITA Corresponding author: Bruno Bordoni, [email protected] Abstract In osteopathic manual medicine (OMM), there are several approaches for patient assessment and treatment. One of these is the five diaphragm model (tentorium cerebelli, tongue, thoracic outlet, diaphragm, and pelvic floor), whose foundations are part of another historical model: respiratory-circulatory. The myofascial continuity, anterior and posterior, supports the notion the human body cannot be divided into segments but is a continuum of matter, fluids, and emotions. In this first part, the neurological relationships of the tentorium cerebelli and the lingual muscle complex will be highlighted, underlining the complex interactions and anastomoses, through the most current scientific data and an accurate review of the topic. In the second part, I will describe the neurological relationships of the thoracic outlet, the respiratory diaphragm and the pelvic floor, with clinical reflections. In literature, to my knowledge, it is the first time that the different neurological relationships of these anatomical segments have been discussed, highlighting the constant neurological continuity of the five diaphragms. Categories: Medical Education, Anatomy, Osteopathic Medicine Keywords: diaphragm, osteopathic, fascia, myofascial, fascintegrity, -

Special Report Vein of Galen Aneurysms

Special Report Vein of Galen Aneurysms: A Review and Current Perspective Michael Bruce Horowitz, Charles A. Jungreis, Ronald G. Quisling, and lan Pollack The term vein of Galen aneurysm encom the internal cerebral vein to form the vein of passes a diverse group of vascular anomalies Galen (4). sharing a common feature, dilatation of the vein Differentiation of the venous sinuses occurs of Galen. The name, therefore, is a misnomer. concurrently with development of arterial and Although some investigators speculate that vein venous drainage systems. By week 4, a primi of Galen aneurysms comprise up to 33% of gi tive capillary network is drained by anterior, ant arteriovenous malformations in infancy and middle, and posterior meningeal plexi (3, 4). childhood ( 1), the true incidence of this a nom Each plexus has a stem that drains into one of aly remains uncertain. A review of the literature the paired longitudinal head sinuses, which in reveals fewer than 300 reported cases since turn drain into the jugular veins ( 3, 4). Atresia of Jaeger et al 's clinical description in 1937 (2). the longitudinal sinuses leads to the develop As we will outline below, our understanding of ment of the transverse and sigmoid sinuses by the embryology, anatomy, clinical presentation, week 7 (3, 4). At birth only the superior and and management of these difficult vascular inferior sagittal, straight, transverse, occipital, malformations has progressed significantly and sigmoid sinuses remain, along with a still over the past 50 years. plexiform torcula (3, 4). On occasion, a tran sient falcine sinus extending from the vein of Embryology and Vascular Anatomy of the Galen to the superior sagittal sinus is seen ( 4). -

Dural Venous Sinuses Dr Nawal AL-Shannan Dural Venous Sinuses ( DVS )

Dural venous sinuses Dr Nawal AL-Shannan Dural venous sinuses ( DVS ) - Spaces between the endosteal and meningeal layers of the dura Features: 1. Lined by endothelium 2. No musculare tissue in the walls of the sinuses 3. Valueless 4.Connected to diploic veins and scalp veins by emmissary veins .Function: receive blood from the brain via cerebral veins and CSF through arachnoid villi Classification: 15 venous sinuses Paried venous sinuses Unpaired venous sinuses ( lateral in position) • * superior sagittal sinus • * cavernous sinuses • * inferior sagittal sinus • * superior petrosal sinuses • * occipital sinus • * inferior petrosal sinuses • * anterior intercavernous • * transverse sinuses • sinus * sigmoid sinuses • * posterior intercavernous • * spheno-parietal sinuses • sinus • * middle meningeal veins • * basilar plexuses of vein SUPERIOR SAGITTAL SINUS • Begins in front at the frontal crest • ends behind at the internal occipital protuberance diliated to form confluence of sinuses and venous lacunae • • The superior sagittal sinus receives the following : • 1- Superior cerebral veins • 2- dipolic veins • 3- Emissary veins • 4- arachnoid granulation • 5- meningeal veins Clinical significance • Infection from scalp, nasal cavity & diploic tissue • septic thrombosis • CSF absorption intra cranial thrombosis (ICT) • Inferior sagittal sinus - small channel occupy • lower free magin of falx cerebri ( post 2/3) - runs backward and • joins great cerebral vein at free margin of tentorium cerebelli to form straight sinus. • - receives cerebral -

The Occipital Emissary Vein: a Possible Marker for Pseudotumor Cerebri

Published May 9, 2019 as 10.3174/ajnr.A6061 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ADULT BRAIN The Occipital Emissary Vein: A Possible Marker for Pseudotumor Cerebri X A. Hedjoudje, X A. Piveteau, X C. Gonzalez-Campo, X A. Moghekar, X P. Gailloud, and X D. San Milla´n ABSTRACT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Transverse sinus stenosis can lead to pseudotumor cerebri syndrome by elevating the cerebral venous pressure. The occipital emissary vein is an inconstant emissary vein that connects the torcular herophili with the suboccipital veins of the external vertebral plexus. This retrospective study compares the prevalence and size of the occipital emissary vein in patients with pseudotumor cerebri syndrome with those in healthy control subjects to determine whether the occipital emissary vein could represent a marker of pseudotumor cerebri syndrome. MATERIALS AND METHODS: The cranial venous system of 46 adult patients with pseudotumor cerebri syndrome (group 1) was studied on CT venography images and compared with a group of 92 consecutive adult patients without pseudotumor cerebri syndrome who underwent venous assessment with gadolinium-enhanced 3D-T1 MPRAGE sequences (group 2). The presence of an occipital emissary vein was assessed, and its proximal (intraosseous) and distal (extracranial) maximum diameters were measured and compared between the 2 groups. Seventeen patients who underwent transverse sinus stent placement had their occipital emissary vein diameters measured before and after stent placement. RESULTS: Thirty of 46 (65%) patients in group 1 versus 29/92 (31.5%) patients in group 2 had an occipital emissary vein (P Ͻ .001). The average proximal and distal occipital emissary vein maximum diameters were significantly larger in group 1 (2.3 versus 1.6 mm, P Ͻ.005 and 3.3 versus 2.3 mm, P Ͻ .001). -

27. Veins of the Head and Neck

GUIDELINES Students’ independent work during preparation to practical lesson Academic discipline HUMAN ANATOMY Topic VEINS OF THE HEAD AND NECK 1. The relevance of the topic: Knowledge of the anatomy of the veins of head and neck is a base of clinical thinking and differential diagnosis for the doctor of any specialty, but, above all, dentists, neurologists and surgeons who operate in areas of the neck or head. 2. Specific objectives - demonstrate superior vena cava, right and left brachiocephalic, subclavian, internal and external jugular, anterior jugular veins and venous angles. - demonstrate dural sinuses, veins of the brain. - demonstrate pterygoid plexus, retromandibular, facial veins and other tributaries of extracranial part of internal jugular vein. - demonstrate external jugular vein. - identify and demonstrate anastomoses on the head and neck. 3. Basic level of preparation Student should know and be able to: 1. To demonstrate the structural features of the cervical vertebrae. 2. To demonstrate the anatomical lesions of external and internal base of the skull. 3. To demonstrate the muscles of the head and neck. 4. To demonstrate the divisions of the brain. 4. Tasks for independent work during preparation for practical lessons 4.1. A list of the main terms, parameters, characteristics that need to be learned by student during the preparation for the lesson Term Definition JUGULAR VEINS Veins that take deoxygenated blood from the head to the heart via the superior vena cava. INTERNAL JUGULAR VEIN Starts from the sigmoid sinus of the dura mater and receives the blood from common facial vein. The internal jugular vein runs with the common carotid artery and vagus nerve inside the carotid sheath. -

Superficial Middle Cerebral Vein SUPERFICIAL CORTICAL VEINS O Superior Cerebral Veins

Cerebral Blood Circulation Khaleel Alyahya, PhD, MEd King Saud University School of Medicine @khaleelya OBJECTIVES At the end of the lecture, students should be able to: o List the cerebral arteries. o Describe the cerebral arterial supply regarding the origin, distribution and branches. o Describe the arterial Circle of Willis . o Describe the cerebral venous drainage and its termination. o Describe arterial & venous vascular disorders and their clinical manifestations. WATCH Review: THE BRAIN o Large mass of nervous tissue located in cranial cavity. o Has four major regions. Cerebrum (Cerebral hemispheres) Diencephalon: Thalamus, Hypothalamus, Subthalamus & Epithalamus Cerebellum Brainstem: Midbrain, Pons & Medulla oblongata Review: CEREBRUM o The largest part of the brain, and has two hemispheres. o The surface shows elevations called gyri, separated by depressions called sulci. o Each hemispheres divided into four lobes by deeper grooves. o Lobs are separated by deep grooves called fissures. Review: BLOOD VESSELS o Blood vessels are the part of the circulatory system that transports blood throughout the human body. o There are three major types of blood vessels: . Arteries, which carry the blood away from the heart. Capillaries, which enable the actual exchange of water and chemicals between the blood and the tissues. Veins, which carry blood from the capillaries back toward the heart. o The word vascular, meaning relating to the blood vessels, is derived from the Latin vas, meaning vessel. Avascular refers to being without (blood) vessels. Review: HISTOLOGY o The arteries and veins have three layers, but the middle layer is thicker in the arteries than it is in the veins: . -

Powerpoint Handout: Lab 1, Part B: Dural Folds, Dural Sinuses, and Arterial Supply to Head and Neck

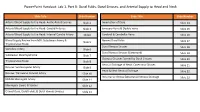

PowerPoint Handout: Lab 1, Part B: Dural Folds, Dural Sinuses, and Arterial Supply to Head and Neck Slide Title Slide Number Slide Title Slide Number Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Aortic Arch Branches Slide 2 Innervation of Dura Slide 14 Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Carotid Arteries Slide 3 Emissary Veins & Diploic Veins Slide 15 Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Internal Carotid Artery Slide4 Cerebral & Cerebellar Veins Slide 16 Blood Supply Review from MSI: Subclavian Artery & Named Dural Folds Slide 5 Slide 17 Thyrocervical Trunk Dural Venous Sinuses Slide 18 Vertebral Artery Slide 6 Dural Venous Sinuses (Continued) Slide 19 Subclavian Steal Syndrome Slide 7 Osseous Grooves formed by Dural Sinuses Slide 20 Thyrocervical Trunk Slide 8 Venous Drainage of Head: Cavernous Sinuses Slide 21 Review: Suprascapular Artery Slide 9 Head & Neck Venous Drainage Slide 22 Review: Transverse Cervical Artery Slide 10 Intracranial Versus EXtracranial Venous Drainage Slide 23 Middle Meningeal Artery Slide 11 Meningeal Layers & Spaces Slide 12 Cranial Dura, Dural Folds, & Dural Venous Sinuses Slide 13 Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Aortic Arch Branches The head and neck receive their blood supply from https://3d4medic.al/PXGmbxEt branches of the right and left common carotid and right and left subclavian arteries. • On the right side, the subclavian and common carotid arteries arise from the brachiocephalic trunk. • On the left side, these two arteries originate from the arch of the aorta. Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Carotid Arteries On each side of the neck, the common carotid arteries ascend in the neck to the upper border of the thyroid cartilage (vertebral level C3/C4) where they divide into eXternal and internal carotid arteries at the carotid bifurcation.