Gaelic Surnominal Place-Names in Ireland and Their Reflection In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Guide to Irish History

Research Guide to Irish History John M. Kelly Library ENCYCLOPEDIAS AND DICTIONARIES CONTENTS Encyclopedia of Irish History and Culture. Edited by James S. Encyclopedias and Dictionaries 1 Collections of Historical Donnelly, Jr. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2004. 2 volumes. Documents 3 [St. Michael’s 1st Floor Reference Area – DA912 .E53 2004] Atlases and Gazetteers 4 Here you will find more than 400 articles on periods of Irish history, Chronologies 4 social institutions, organisations and important individuals; each article Biography 5 includes a bibliography of the most important books and journal Bibliographies 5 articles. The full-text of more than 150 primary documents in the Historical Newspapers 6 encyclopedia is a bonus. Finding Journal Articles 7 Dictionary of Irish Biography: from the Earliest Times to the Year 2002. Edited by James McGuire and James Quinn. Cambridge: Royal Irish Academy and Cambridge University Press, 2009. 9 volumes. [St. Michael’s 1st Floor Reference Area – CT862 .D53 200 9] With more than 9,000 articles on subjects ranging from politics, law, engineering and religion to literature, painting, medicine and sport, this widely-praised encyclopedia is the place to start for Irish biography. Articles are signed and contain bibliographies. So detailed is the 9-volume set that you get thorough articles on a wide range of people, from internationally-famous figures such as the poet W.B. Yeats to lesser-known persons such as Denis Kilbride, a 19 th Century agrarian campaigner and MP. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Edited by John H. Koch. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2006. 5 volumes. [Available online for UofT use only: www.library.utoronto.ca/] [St. -

The Irish Crokers Nick Reddan

© Nick Reddan Last updated 2 May 2021 The Irish CROKERs Nick Reddan 1 © Nick Reddan Last updated 2 May 2021 Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2 Background ................................................................................................................................ 4 Origin and very early records ................................................................................................ 4 Acknowledgments.................................................................................................................. 5 Note ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Origin ......................................................................................................................................... 6 The Settlers ................................................................................................................................ 9 The first wave ........................................................................................................................ 9 The main group .................................................................................................................... 10 Lisnabrin and Nadrid ............................................................................................................... 15 Dublin I ................................................................................................................................... -

Ireland Ireland Is Not the Prime Concern of This Website, and Its Main Author Cannot Claim to Know Its Landscape and History Really Well

Ireland Ireland is not the prime concern of this website, and its main author cannot claim to know its landscape and history really well. Nevertheless Ireland does offer useful insights into the earliest geographical names of western Europe, because it was never conquered by the Roman army. Importantly, there is just one main source for its earliest names: Ptolemy’s Geography names 53 of them. So all of Ireland can be tackled in this one article. The locations of Ptolemy’s Irish names have long been discussed, with recent attempts to improve the logic by Darcy and Flynn (2008), Kleineberg, Marx, and Lelgemann (2012), Warner (2013), and Counihan (2019). The present article was begun partly to help the work of Dmitri Gusev and colleagues, which is still only partly published at a conference. It takes the best Greek spellings from Stückelberger and Graßhoff (2006). Each name is transcribed once into the Latin alphabet and its position in Ptolemy’s text is reported as 2,2,2 or similar. In the words of one website: “The tribal and place-names in Ireland listed by Ptolemy were Celtic, and many survive in Old or Middle Irish forms.” This is a reasonable view, but the hard work of historical linguists (notably de Bernardo Stempel, 2000,2005) to find parallels in Celtic languages for elements in early Irish names has had disappointingly little success. This led Mallory (2013) to stress how much Ptolemy’s text might have been corrupted over the centuries. However, as name- to-place assignments have improved, with better geographical understanding and access to reliable texts, the linkage between Ireland’s earliest names and written Celtic languages has got weaker. -

A Case Study of Present Day Waterford County, Ireland

POWER IN PLACE-NAMES: A CASE STUDY OF PRESENT DAY WATERFORD COUNTY, IRELAND A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Jessica E. Greenwald August 2005 This thesis entitled POWER IN PLACE-NAMES: A CASE STUDY OF PRESENT DAY WATERFORD COUNTY, IRELAND by JESSICA E. GREENWALD has been approved for the Department of Geography and the College of Arts and Sciences by Timothy Anderson Associate Professor of Geography Benjamin M. Ogles Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences GREENWALD, JESSICA E. M.A. August 2005. Geography PowerU In Place-Names: A Case Study Of Present Day Waterford County, Ireland (85U pp.) Director of Thesis: Timothy Anderson This study investigates the present day toponymns of Waterford County, Ireland. By using the Land Ordnance Survey of Ireland maps, a database was created with the place names of the county. This study draws upon both traditional and contemporary theories and methods in Geography to understand more fully the meaning behind the place names on a map. In the “traditional” sense, it focuses on investigating changes in the landscape wrought by humans through both time and space (the naming of places). In a more “contemporary” sense, it seeks to understand the power relationships and social struggles reflected in the naming of places and the geography of those names. As such, this study fills a void in the current toponymns and cartographic literature, which are both focused mainly on patterns of diffusion and power struggles in North America. -

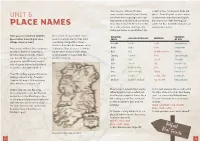

Place Names UNIT 6 All of Them Were Originally in Irish, but in Ireland Were Translated Into English

There are more than 62,000 place English tongue for all towns, lands and names on the island of Ireland. Nearly places’. From this point on, place names UNIT 6 all of them were originally in Irish, but in Ireland were translated into English. King Charles II decided to do something Below are some of the formerly Irish PLACE NAMES about that in 1664 AD. He declared that words that have found their way into our the people of Ireland ‘shall have new modern place names. and proper names more suitable to the After a while the name Ulaid came to Have you ever wondered what the ORIGINAL EXAMPLE place names mean in your area, mean the land where this tribe lived. IRISH ENGLISH SPELLING MEANING OF USE The Vikings changed this name to village, street or town? Achadh Augh Field Aughnacloy Ulaidstir. After that the Normans called Place names in Ulster, like everywhere it Uluestere. That, of course, is how we Baile Bally Town Ballymena in Ireland, date from hundreds or, get the name Ulster. In Irish, Ulster Béal Bel Mouth of a river Belfast in some cases, thousands of years is called Ulaidh or Cúige Uladh (the Carraig Carrick Rock Carrickfergus ago. Around 1800 years ago, a Greek province of Ulster). Cill Kill Church Shankill geographer called Ptolemy made a map of Europe that included Ireland. Cnoc Knock Hill Knockbreda You can see this map on page 9. Dún Down or Dun Fort Downpatrick Inis Inish or Ennis Island Enniskillen The 17th century engraver Wenceslas Loch Lough Lough, Lake Loughuile Hollar produced a map of Ireland. -

RELIGION, WAR, and CHANGING LANDSCAPES: an HISTORICAL and ECOLOGICAL ACCOUNT of the YEW TREE (Taxus Baccata L.) in IRELAND

RELIGION, WAR, AND CHANGING LANDSCAPES: AN HISTORICAL AND ECOLOGICAL ACCOUNT OF THE YEW TREE (Taxus baccata L.) IN IRELAND By J. L. DELAHUNTY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2002 This work is dedicated to the Lord and Mickey. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I cannot thank my assistants, both friends and family, in Ireland enough: Colin McCowan, Richard and Judy Delahunty, Con Foley, Tom Millane, and Dr. Lee. I also wish to thank my family and friends in America who aided tremendously in this endeavor: Olivia Perry-Smith, Art Frieberg, Desiree Price, Terry Lucansky, Tim Burke, and John Stockwell. Of course, I could not have done this without help from my mentors at the Geography Department: Mike Binford, Pete Waylen, and Ary Lamme. Other academics who aided in this research were William Kenney, Mark Brenner, Jason Curtis, David Dilcher, Fraser Mitchell, Edwina Cole, Tara Nolan, Bob Devoy, Mike Baillie, and David Brown. Finally, I give thanks to the Lord for creating the majestic yew tree and the beautiful island of Ireland and blessing me with the finest of family and friends. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iii LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................................... viii LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... -

Sliabh in Irish Place-Names Paul Tempan

Sliabh in Irish Place-Names1 Paul Tempan Queen’s University, Belfast The word sliabh is one of the most common generic elements in Irish hill and mountain names. Along with binn, cnoc, cruach and mullach, I made it the object of study for a Masters dissertation in 2004. Concern- ing sliabh, I noted that it is found widely throughout all 4 provinces of Ireland and that, in common with all the other elements studied, it can be applied to hills and mountains of greatly varying heights.2 As a common noun, sliabh is the word most likely to be found in English-Irish dictionaries as a translation for ‘mountain’, and it forms the basis for a number of derivatives, e.g. sléibhteoir ‘mountaineer’ and sléibhtiúil ‘mountainous’. However, these simple statements belie the remarkable complexity of the word in terms of its wide range of mean- ings and problematic etymology. In the dissertation I found that it was semantically and structurally the most complex of the 5 elements 1 This is a revised version of a paper delivered to the Society’s Autumn Confer- ence, ‘Placing Names: A Study Day’, held at the University of Chichester on 25th October 2008. The information on sliabh in townland names is taken from a later paper delivered to the Scottish Place-Name Society at their Spring Conference in New Galloway on 9th May 2009. It has been a long time in the making, as the first draft was written in 2002, shortly after attending the Scottish Place-Name Society’s Autumn Conference in Aviemore. -

Finding Your Irish Ancestors: a Beginner's Guide

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ouimette, David S. Finding your Irish ancestors : a beginner’s guide / by David S. Ouimette. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 9781618589712 ISBN 13: 978-1-59331-293-0 (softcover : alk. paper) 1. Ireland-Genealogy- Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Irish Americans—Genealogy—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title. CS483.095 2005 929’.1’0720415-dc22 2005021165 Copyright © 2005 The Generations Network, Inc. Published by Ancestry Publishing, a division of The Generations Network, Inc. 360 West 4800 North Provo, Utah 84604 All rights reserved. All brand and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages for review. First Printing 2005 1098765432 2 978-1-59331-293-0 Printed in the United States of America. In memory of my grandfathers, William O’Connor (1888-1944) of Mulgrave Bridge, Ballyard, County Kerry, and George Gilbert Love (1893-1978) of Abbeylara, County Longford Kylemore Abbey, Ireland. Table of Contents Title Page Copyright Page Table of Figures Acknowledgments Introduction 1 - Basic Principles 2 - Time Line of Irish History 3 - Surnames and Given Names 4 - Place Names and Land Divisions 5 - The Irish Overseas 6 - Birth, Marriage, and Death Certificates 7 - Church Records 8 - Censuses and Census Substitutes 9 - Land and Property Records 10 - Gravestone Inscriptions 11 - Newspapers 12 -

Nationalism in Ireland: Archaeology, Myth, and Identity

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Nationalism In Ireland: Archaeology, Myth, And Identity Elaine Kirby Tolbert University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Tolbert, Elaine Kirby, "Nationalism In Ireland: Archaeology, Myth, And Identity" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 362. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/362 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism in Ireland: Archaeology, Myth, and Identity A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology The University of Mississippi by: Elaine Tolbert May 2013 Copyright Elaine Tolbert 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT A nation is defined by a collective identity that is constructed in part through interpretation of past places and events. In this paper, I examine the links between nationalism and archaeology and how the past is used in the construction of contemporary Irish national identity. In Ireland, national identity has been influenced by interpretation of ancient monuments, often combining the mythology and the archaeology of these sites. I focus on three celebrated monumental sites at Navan Fort, Newgrange, and the Hill of Tara, all of which play prominent roles in Irish mythology and have been extensively examined through archaeology. I examine both the mythology and the archaeology of these sites to determine the relationship between the two and to understand how this relationship between mythology and archaeology influences Irish identity. -

Colonization and County Cork's Changing Cultural Landscape: The

Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society www.corkhist.ie Title: Colonization and County Cork's changing cultural landscape: the evidence from placenames Author: O'Flanagan, Patrick Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society , 1979, Vol. 84, No. 239, page(s) 114 Published by the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society Digital file created: October 28, 2016 Your use of the JCHAS digital archive indicates that you accept the Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://corkhist.ie/termsandconditions/ The Cork Historical and Archaeological Society (IE148166, incorporated 1989) was founded in 1891, for the collection, preservation and diffusion of all available information regarding the past of the City and County of Cork, and South of Ireland generally. This archive of content of JCHAS (from 1892 up to ten years preceding current publication) continues the original aims of the founders in 1891. For more information visit www.corkhist.ie. This content downloaded from www.corkhist.ie All use subject to CHAS Terms and Conditions Digital content (c) CHAS 2016 C I ] Part i— Vol. L X X X IV N o . 239 JANUARY-JUNE I979 Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society {Eighty-seventh year of issue) Colonization and County Cork’s Changing Cultural Landscape: the Evidence from Placenames By PATRICK O’FLANAGAN The notion of a cultural landscape is one which embraces the man made or man modified landscape differentiating it from the largely unmodified physical landscape. The cultural landscape consists of two major elements, firstly there are the visible elements, such as, cities, houses, byres, fields and ditches. -

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T08:30:22Z 4-Hickey:Lost Ch 1 New 31/10/2008 12:32 Page 29

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cork Open Research Archive Title Where have all the wolves gone? Author(s) Hickey, Kieran R. Editor(s) Fenwick, Joe Publication date 2009 Original citation Hickey, K. R. (2009) 'Where have all the wolves gone?', in Fenwick, J. (ed.) Lost and found II: rediscovering Ireland's past. Dublin: Wordwell, pp. 29-40. ISBN 978-1-905569-26-7 Type of publication Book chapter Link to publisher's http://wordwellbooks.com/index.php?route=common/home version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/2647 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T08:30:22Z 4-Hickey:Lost ch 1 new 31/10/2008 12:32 Page 29 4 Where have all the wolves gone? Kieran Hickey One of the interesting aspects of doing research on any topic is the fascinating material you come across, often not directly related to what you are looking for but terrifically interesting in its own right. From both my early days as a student and from my climate history research I became vaguely aware that there had been real wild wolves in Ireland right up until late medieval times. Wolves, apparently, had survived longer in Ireland than in England, Wales or Scotland. This fact absolutely fascinated me and, being aware that very little had been done on native Irish wolves before, the germ of a little side-research project began to take shape at the back of my mind. -

Bealtaine in Irish and Scottish Place-Names

Bealtaine in Irish and Scottish Place-names Kay Muhr Ulster Place-Name Society The term Bealtaine (older spelling Beltine), attested from the Early Irish period, appears in a small number of Irish and Scottish place-names. In Ireland there are possibly ten, most of which are names of townlands in the north (of which two are now obsolete); in the south, there is a townland in Co. Tipperary and one in Co. Cork. In Scotland, Tullybelton PER is the earliest attested of all such names. Bealtaine is used as the name of a time of year, May Day or the month of May. This day was significant both as a quarter day beginning the summer, when young animals increased in value and were taken to their summer grazing, and for the lighting of ceremonial bonfires, the ritual also known as Bealtaine.1 The term Bealtaine was common to the Gaelic-speaking area, including Man,2 while the fire ritual has parallels throughout Europe.3 This paper will study some accounts of what happened during the season of Bealtaine in Ireland and Scotland, and consider the various attempts to explain the origin of the term. This is followed by the history and topography of the place-names containing Bealtaine, in order to compare what is known of the traditions and their development with the origin of the place-names themselves. Bealtaine in the Gaelic year The Early Irish year was divided into four seasons, apparently beginning, not at the equinox or solstice, but between them. All four quarter days, counted from the night before, are mentioned in the Early Irish story of Cú Chulainn’s wooing of his wife Emer.