Video Games and Andrew Norman's Play [Final Draft V.3]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Release: Tk, 2013

FOR RELEASE: January 23, 2013 SUPPLEMENT CHRISTOPHER ROUSE, The Marie-Josée Kravis COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE WORLD PREMIERE of SYMPHONY NO. 4 at the NY PHIL BIENNIAL New York Premiere of REQUIEM To Open Spring For Music Festival at Carnegie Hall New York Premiere of OBOE CONCERTO with Principal Oboe Liang Wang RAPTURE at Home and on ASIA / WINTER 2014 Tour Rouse To Advise on CONTACT!, the New-Music Series, Including New Partnership with 92nd Street Y ____________________________________ “What I’ve always loved most about the Philharmonic is that they play as though it’s a matter of life or death. The energy, excitement, commitment, and intensity are so exciting and wonderful for a composer. Some of the very best performances I’ve ever had have been by the Philharmonic.” — Christopher Rouse _______________________________________ American composer Christopher Rouse will return in the 2013–14 season to continue his two- year tenure as the Philharmonic’s Marie-Josée Kravis Composer-in-Residence. The second person to hold the Composer-in-Residence title since Alan Gilbert’s inaugural season, following Magnus Lindberg, Mr. Rouse’s compositions and musical insights will be highlighted on subscription programs; in the Philharmonic’s appearance at the Spring For Music festival; in the NY PHIL BIENNIAL; on CONTACT! events; and in the ASIA / WINTER 2014 tour. Mr. Rouse said: “Part of the experience of music should be an exposure to the pulsation of life as we know it, rather than as people in the 18th or 19th century might have known it. It is wonderful that Alan is so supportive of contemporary music and so involved in performing and programming it.” 2 Alan Gilbert said: “I’ve always said and long felt that Chris Rouse is one of the really important composers working today. -

2018/19 Utah Symphony | Utah Opera Season Calendar

2018/19 UTAH SYMPHONY | UTAH OPERA SEASON CALENDAR DATE TIME CONCERT PROGRAM CONDUCTOR / ARTISTS VENUE SERIES 11 7:00 PM 59th Annual Salute to Youth Conner Gray Covington conductor AH 14 & 15 7:30 PM Bernstein on Broadway Teddy Abrams conductor Morgan James vocalist AH Barlow Bradford Thierry Fischer conductor chorus director ANDREW NORMAN Suspend a fantasy for piano and orchestra Jason Hardink piano Kirstin Chávez mezzo-soprano 21 & 22 7:30 PM Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 “Choral” Joélle Harvey soprano AH A, D Issachah Savage tenor Patrick Carfizzi bass-baritone SEPTEMBER Utah Symphony Chorus University of Utah Choirs GERSHWIN An American in Paris 28 7:30 PM An American in Paris RAVEL Piano Concerto in G Thierry Fischer conductor Alexandre Tharaud piano AH B, E 29 5:30 PM SCHUBERT Symphony No. 9 “The Great C Major” 13 7:30 PM 15 7:00 PM Robert Tweten conductor Vera Calábria director 17 7:00 PM Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet CT Joshua Dennis Romeo Anya Matanoviĉ Juliet 19 7:30 PM 21 2:00 PM 26 7:30 PM BERNSTEIN Three Dances from Fancy Free OCTOBER Tchaikovsky’s 4th & The Red Violin 27 5:30 PM JOHN CORIGLIANO Violin Concerto “The Red Violin” Andrew Litton conductor Philippe Quint violin AH B, E 26 10:00 AM LITTON/QUINT FINISHING TOUCHES OPEN REHEARSAL TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 4 2 & 3 7:00 PM Ghostbusters in Concert Peter Bernstein conductor Utah Symphony AH Thierry Fischer conductor Garnett Bruce director James Sale lighting designer Jonathan Johnson Candide B, E 9 7:30 PM Bernstein’s Candide with the Utah Symphony BERNSTEIN Candide Lauren Snouffer Cunegonde Hugh Russell Dr. -

Premieres by Caroline Shaw and Tyshawn Sorey Concluding

PRESS RELEASE [email protected] | (650) 525-6288 View Press Kits San Francisco Contemporary Music Players Present Premieres by Caroline Shaw and Tyshawn Sorey, with Concluding Concerts of 50th Anniversary Season to be Webcast in June and July SAN FRANCISCO (June 3, 2021) – San Francisco Contemporary Music Players and Artistic Director Eric Dudley announce three upcoming online events, including the world premieres of newly-commissioned works by acclaimed composers Caroline Shaw and Tyshawn Sorey, both Creative Advisors to SFCMP. For the first program, with webcast starting at 8 pm on Friday June 18 and available on-demand for 30 days following, Caroline Shaw brings her own insights as a vocalist to a new work for mixed quartet and solo voice, entitled Pine Tree and based on a text by San Francisco poet Yone Noguchi (1875-1947). Born in Japan and returning there for the latter part of his life, Noguchi spent a number of his early creative years in San Francisco and was the first Japanese-born writer to publish poetry in English. His poem I Hear you Call, Pine Tree becomes the basis for Shaw’s piece, which also features SFCMP Creative Advisor and guest artist Pamela Z on vocals. The rest of the program includes other works of vocal or vocally-inspired music, with Pamela Z performing her own composition Breathing from Carbon Song Cycle, Andrew Norman’s beautifully lyrical work Sabina for solo violin, and John Adams’s Son of Chamber Symphony, with its raucous opening movement built upon rhythmic echoes of the scherzo from Beethoven’s 9th, ‘Choral’ symphony. -

Commissions and Premieres

Commissions and Premieres In its 2020–2021 season, Carnegie Hall continues its longstanding commitment to the music of tomorrow, commissioning 19 works, and presenting 8 world and 24 New York premieres. This includes daring new solo, chamber, and orchestral works by established and emerging composers, as well as thought-provoking performances that cross musical genres. Carnegie Hall Commissions COMPOSER TITLE PERFORMERS THOMAS ADÈS Angel Symphony City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (NY Premiere, co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall) Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, Music Director and Conductor LERA AUERBACH New Work Artemis Quartet (NY Premiere, co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall) KINAN AZMEH New Work Kinan Azmeh Cityband (World Premiere, commissioned by Carnegie Hall) LISA BIELAWA Sanctuary American Composers Orchestra (NY Premiere, co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall) George Manahan, Music Director and Conductor Jennifer Koh, Violin TYONDAI BRAXTON New Work Third Coast Percussion (NY Premiere, co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall) Movement Art Is feat. Jon Boogz & Lil Buck, Co-Founders, Choreographers, and Movement Artists OSVALDO GOLIJOV Falling Out of Time Silkroad Ensemble (NY Premiere, co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall) JLIN New Work Third Coast Percussion (NY Premiere, co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall) Movement Art Is feat. Jon Boogz & Lil Buck, Co-Founders, Choreographers, and Movement Artists VLADIMIR MARTYNOV New Work Kronos Quartet (NY Premiere, co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall) JESSIE MONTGOMERY Divided Sphinx Virtuosi (NY Premiere, co-commissioned -

Symphonie Fantastique

CLASSICAL�SERIES SYMPHONIE FANTASTIQUE THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 7, AT 7 PM FRIDAY & SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 8 & 9, AT 8 PM NASHVILLE SYMPHONY THIERRY FISCHER, conductor STEPHEN HOUGH, piano ANDREW NORMAN Unstuck – 10 minutes FELIX MENDELSSOHN Concerto No. 1 in G Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 25 – 21 minutes Molto allegro con fuoco Andante Presto – Molto allegro e vivace Stephen Hough, piano – INTERMISSION – HECTOR BERLIOZ Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14 – 49 minutes Reveries and Passions A Ball Scene In the Country March to the Scaff old Dream of a Witches' Sabbath This concert will last one hour and 55 minutes, including a 20-minute intermission. This concert will be recorded live for future broadcast. To ensure the highest-quality recording, please keep noise to a minimum. INCONCERT 19 CLASSICAL PROGRAM SUMMARY How do young artists find a unique voice? This program brings together three works, each written when their respective composers were only in their 20s. The young American Andrew Norman was already tapping into his gift for crafting vibrantly imaginative, almost hyper-active soundscapes in Unstuck, the brief but event-filled orchestral piece that opens our concert. Felix Mendelssohn had already been in the public eye as a child prodigy before he embarked on a series of travels across Europe from which he stored impressions for numerous mature compositions — including the First Piano Concerto. Just around the time Mendelssohn wrote this music, his contemporary Hector Berlioz was refining the ideas that percolate in his first completed symphonic masterpiece. The Symphonie fantastique created a sensation of its own with its evocation of a tempestuous autobiographical love affair through an unprecedentedly bold use of the expanded Romantic orchestra. -

Jupiter String Quartet – Group Biography

Jupiter String Quartet – Group Biography The Jupiter String Quartet is a particularly intimate group, consisting of violinists Nelson Lee and Meg Freivogel, violist Liz Freivogel (Meg’s older sister), and cellist Daniel McDonough (Meg’s husband, Liz’s brother-in-law). Now enjoying their 16th year together, this tight-knit ensemble is firmly established as an important voice in the world of chamber music. In addition to their performing career, they are artists- in-residence at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana, where they maintain private studios and direct the chamber music program. The quartet has performed across the United States, Canada, Europe, Asia, and the Americas in some of the world’s finest halls, including New York City’s Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center, London’s Wigmore Hall, Boston’s Jordan Hall, Mexico City's Palacio de Bellas Artes, Washington, D.C.’s Kennedy Center and Library of Congress, Austria’s Esterhazy Palace, and Seoul’s Sejong Chamber Hall. Their major music festival appearances include the Aspen Music Festival and School, Bowdoin Music Festival, Lanaudiere Festival, West Cork (Ireland) Chamber Music Festival, Caramoor International Music Festival, Music at Menlo, Maverick Concerts, Madeline Island Music Festival, Rockport Music Festival, the Banff Centre, Yellow Barn Festival, Skaneateles Festival, Encore Chamber Music Festival, and the Seoul Spring Festival, among others. Their chamber music honors and awards include the grand prizes in the Banff International String Quartet Competition and the Fischoff National Chamber Music Competition in 2004. In 2005, they won the Young Concert Artists International auditions in New York City, which quickly led to a busy touring schedule. -

Andrew Norman

THE 2020–2021 RICHARD AND BARBARA DEBS COMPOSER’S CHAIR Andrew Norman Craig T. Mathew T. Craig Andrew Norman has been appointed holder of the Richard and Barbara Debs Composer’s Chair at Carnegie Hall for the 2020–2021 season. One of the most sought-after voices in American classical music and named Musical America’s 2017 Composer of the Year, his music surprises, delights, and thrills with its visceral power and intricate structures. Fascinated by how technology has changed the ways in which we think, feel, act, and perceive, Mr. Norman writes music that is both a reflection of—and refuge from—our fast and fragmented world. Striking colors, driving energy, and underlying lyricism are all present in the work of a composer who defies traditional labels. During his nine-concert residency that kicks off in October, Mr. Norman’s Violin Concerto (co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall) receives its New York premiere with Leila Josefowicz and the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by Gustavo Dudamel. Mr. Norman’s music will also be performed by the Berliner Philharmoniker led by Kirill Petrenko, the Louisville Orchestra led by Teddy Abrams, pianist Emanuel Ax, Ensemble Connect, yMusic, and the American Composers Orchestra. Committed to the development of new work by emerging composers, Mr. Norman curates a program for the LA Phil New Music Group and participates in the Weill Music Institute’s All Together: A Global Ode to Joy as part of his residency. Andrew Norman’s work draws on an eclectic mix of sounds and performance practices, and is deeply influenced by his training as a pianist and violist, as well as his lifelong love of architecture. -

New York Philharmonic Young People's Concert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 1, 2019 Contact: Deirdre Roddin (212) 875-5700; [email protected] NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC YOUNG PEOPLE’S CONCERT Music Across Borders: “Level Up — Beethoven, Andrew Norman, and Video Games” Andrew NORMAN’s Level I, from Play Allegro con brio from BEETHOVEN’s Symphony No. 5 WORLD PREMIERE of VERY YOUNG COMPOSER Kyler Simon’s The Great Adventure Edwin Outwater To Conduct Nadia Sirota To Host Featuring Composer Andrew Norman and Animation by Steven Mertens Directed by Habib Azar Saturday, March 2, 2019 The 96th season of the New York Philharmonic Young People’s Concerts (YPCs) will continue on Saturday, March 2, 2019, at 2:00 p.m. with “Level Up — Beethoven, Andrew Norman, and Video Games,” the third program in this season’s series of YPCs, Music Across Borders. Conducted by Edwin Outwater, hosted by The Marie-Josée Kravis Creative Partner Nadia Sirota, and directed by Habib Azar, the program will explore how writing music is like playing a video game — specifically, how the development section of a piece is like creating your own story in a video game. The program will illustrate the concept through the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5; Level I from Play by Andrew Norman, who will speak about his piece; and a new work by 12-year-old Philharmonic Very Young Composer Kyler Simon, who will talk about the process of writing his piece in a video and onstage. Animation by Steven Mertens will accompany the performances of the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and Level I from Andrew Norman’s Play. -

PIANO KAPUSTIN: a Recap of Recent Classical Releases

HAL LEONARD WIN T ER 2019 UPDATE NIKOLAI Within this newsletter you will find PIANO KAPUSTIN: a recap of recent classical releases. HUMORESQUE, The following classical catalogs are JOHANN SEBASTIAN OP. 75 distributed by Hal Leonard: BACH/JOHANNES Schott BRAHMS: CHACONNE The Humoresque Op. 75 Alphonse Leduc FROM PARTITA NO. 2 IN D — composed in 1994 — is Associated Music MINOR considered one of the most Publishers ARRANGEMENT FOR PIANO, difficult pieces by Kapustin. Boosey & Hawkes LEFT-HAND Presented in the standard jazz Bosworth Music form, the variations sound like Henle Urtext Edition Bote & Bock The D-minor Chaconne is improvisations, influenced by undoubtedly the most famous McCoy Tyner’s style, but are minutely through-composed. Chester Music movement of all of Bach’s 6 49046035 ......................................................................$16.99 DSCH Sonatas and Partitas for violin. Editio Musica Budapest So it is hardly surprising that it has seen many arrangements. Editions Durand Johannes Brahms marvelled at how a single staff of music could SERGEI RACHMANINOFF: offer “a whole world of the deepest thoughts and the mightiest PIANO SONATA NO. 2 IN Editions Max Eschig emotions.” He promptly made his own arrangement for piano, B-FLAT MINOR, OP. 36 Editions Musicales left hand alone. 1913 & 1931 VERSIONS Transatlantique 51481187 ........................................................................$11.95 ed. Dominik Rahmer, fing. Editions Salabert Marc-André Hamelin Ediciones Henle Urtext Edition Joaquín Rodrigo FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN: Includes both Rachmaninoff’s Edward B. Marks SCHERZI original 1913 version and Music Company ed. Norbert Müllemann edited 1931 version of this Eulenburg fing. Hans-Martin Theopold substantial piece, with Forberg Henle Urtext Edition fingerings by Marc-André 51480886 ........................$25.95 Hamelin. -

In the COMMUNITY Series in the LABORATORY Series MASTERCLASS Series at the CROSSROADS Series How Music Is Made ONLINE 50Th Anniv

DUDLEY SOREY LIM Z SHAW WILSON FURE REID ADAMS ATLADOTTIR 50th Anniversary Season SFCMP.org ABOUT SAN FRANCISCO CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PLAYERS San Francisco Contemporary Music Players is the West Coast’s most longstanding and largest new music ensemble, comprised of twenty-two highly skilled musicians. For 50 years, the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players have created innovative and artistically excellent music and are one of the most active ensembles in the United States dedicated to contemporary music. Holding an important role in the regional and national cultural landscape, the Contemporary Music Players are a 2018 awardee of the esteemed Fromm Foundation Ensemble Prize, and a ten-time winner of the CMA/ASCAP Award for Adventurous Programming. WELCOME TO OUR 2020-21 SEASON ERIC DUDLEY, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR The Lineup THE CONTEMPORARY PLAYERS View Bios Tod Brody, flute Meredith Clark, harp Kyle Bruckmann, oboe Kate Campbell, piano Sarah Rathke, oboe David Tanenbaum, guitar Jeff Anderle, clarinet Hrabba Atladottir, violin Peter Josheff, clarinet Susan Freier, violin Adam Luftman, trumpet Roy Malan, violin Brendan Lai-Tong, trombone Meena Bhasin, viola Peter Wahrhaftig, tuba Nanci Severance, viola Chris Froh, percussion Hannah Addario-Berry, cello Haruka Fujii, percussion Stephen Harrison, cello Loren Mach, percussion Richard Worn, contrabass William Winant, percussion GUEST ARTISTS Allegra Chapman, piano Alicia Telford, horn Shawn Jones, bassoon Pamela Z, voice Jamael Smith, bassoon FEATURING THE WORK OF Aaron Jay Kernis John Adams Amadeus -

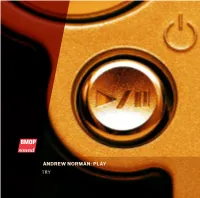

ANDREW NORMAN: PLAY TRY ANDREW NORMAN B

ANDREW NORMAN: PLAY TRY ANDREW NORMAN b. 1979 PLAY PLAY (2013) TRY [1] Level 1 12:24 [2] Level 2 20:57 [ ] BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT 3 Level 3 12:45 GIL ROSE, CONDUCTOR [4] TRY (2011) 13:58 TOTAL 60:07 COMMENT By Andrew Norman I wish you all could see Play performed live. The symphony orchestra is, for me, an instrument that needs to be experienced live. It is a medium as much about human energy as it is about sound, as much about watching choices being made and thoughts exchanged and feats of physical coordination performed as it is about listening to the melodies and harmonies and rhythms that result from those actions. As its name might suggest, Play is an exploration of the many ways that people in an orchestra can play with, against, or apart from one another. Like much of my music, it tries to make the most of the innate physicality and theatricality of live instrumental performance. Play is very directly concerned with how and when and why players move—with the visual as well as the aural spectacle that is symphonic music—and as such there are layers of its meaning and structure that might be difficult to discern on an audio recording. So you, the listener of this album, will have to use your imagination, as you are not going to see much of what defines Play’s expressive world. You’re not going to see how the conductor does or doesn’t control the goings-on at any particular moment. -

Jasper String Quartet

Jasper String Quartet CONTACT Jasper String Quartet 205 Forrest Ave Elkins Park, PA 19027 PHONE (314) 607-2042 email | website Biography QUOTES Winner of the prestigious CMA Cleveland Quartet Award, Philadelphia's Jasper String Quartet is the “The [Jasper String Quartet] Professional Quartet in Residence at Temple University's Center for Gifted Young Musicians. displayed joie de vivre and The Jaspers have been hailed as “sonically delightful and expressively compelling” (The Strad) and athleticism - and perhaps most "powerful" (New York Times). "The Jaspers... match their sounds perfectly, as if each swelling chord were tellingly, grins all around.” coming out of a single, impossibly well-tuned organ, instead of four distinct instruments." (New Haven Advocate) – The Strad The quartet records exclusively for Sono Luminus and have released three highly acclaimed albums - Beethoven Op. 131, The Kernis Project: Schubert, and The Kernis Project: Beethoven. “The Jasper Quartet generates an electricity that seems to Current Projects crackle through the crowd.” The Quartet rounds out their commission tour of Aaron Jay Kernis’ 3rd String Quartet "River" in 2016-17 with performances at Wigmore Hall and at Classic Chamber Concerts in Florida. The – Naples Daily News Quartet's Carnegie Hall Recital of the work last season received a glowing review in The Strad. “The music breathed and The Quartet will release their latest album with Sono Luminus in early 2017 featuring quartets by Donnacha Dennehy, Annie Gosfield, Judd Greenstein, Ted Hearne, David Lang, Missy Mazzoli, and swelled in an expressive way Caroline Shaw. without being over-calculated. In addition, this season they will launch their inaugural season of Jasper Chamber Concerts, a series in Even the moments of silence Philadelphia devoted to world class performances of masterworks from around the world and vibrated with an energy.” Philadelphia.