Quality Public Service Through Collaborative Governance in the Philippines: Focus on Selected 2018 Galing Pook Awardees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippine Airlines' Laboratory and Testing Partners for Philippine Domestic Travel

Philippine Airlines’ Laboratory and Testing Partners for Philippine Domestic Travel RAPID TEST AND RT-PCR TEST PARTNER One Health Medical Services, Inc. ADDRESS: OHM Building, Andrews Avenue (beside PAL Gate 1A), MIAA Zone, Pasay City 1300 LANDLINE: (+632) 8938-6680 to 81 MOBILE: (+639) 66-561-7639 E-MAIL: [email protected] RELEASE OF TEST RESULTS: 20 min for Rapid Tests, 24-48 hrs for RT-PCR Tests RT-PCR TEST PARTNERS Cardinal Santos Medical Center Fe Del Mundo Medical Center ADDRESS: 10 Wilson, Greenhills West, San Juan 1502 ADDRESS: 11 Banawe st. Brgy Dona Josefa, Quezon City LANDLINE: (+632) 8724-3997 LANDLINE: (+632) 8712-0845 loc 1903 and 1601 MOBILE: (+639) 49-333-5489 MOBILE: (+639) 17-5583-726 E-MAIL: [email protected] E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.csmceconsult.com WEBSITE: www.fedelmundo.com.ph RELEASE OF TEST RESULTS: 72-120 hrs RELEASE OF TEST RESULTS: 48-72 hrs Kaiser Medical Center New World Diagnostics WEBSITE: https://appointments.kaisermedcenter.com/pal WEBSITE: https://www.nwdi.com.ph/ RELEASE OF TEST RESULTS: 24 hrs RELEASE OF TEST RESULTS: 48-72 hrs (excl. Sun) MAKATI CITY QUEZON CITY ADDRESS: G/F King's Court Building 1, 2129 Don Chino ADDRESS: 205 D. Tuazon Street, Brgy. Maharlika, Roces Avenue, Makati City Quezon City, Philippines LANDLINE: (+632) 8804-9988 LANDLINE: (+632) 8790-8888, local 218 or 225 MOBILE: (+639) 17-577-3886 MOBILE: OIC – Laboratory Manager Gretchen Catli: E-MAIL: [email protected] (+639) 17-530-1143, Sales & Marketing Manager Rio E. Barrozo: (+639) 16-453-5662 MANILA CITY E-MAIL: [email protected], ADDRESS: G/F Robinsons Place Ermita, Manila [email protected] LANDLINE: (+632) 8353-0495 MOBILE: (+639) 17-183-5488 QUEZON CITY E-MAIL: [email protected] ADDRESS: G/F Hipolito Bldg. -

Comprehensive Land Use Plan 2016 - 2025

COMPREHENSIVE LAND USE PLAN 2016 - 2025 PART 3: SECTORAL PROFILE 3.1. INFRASTRUCTURE, FACILITIES AND UTILITIES 3.1.1. Flood Control Facilities 3.1.1.1. “Bombastik” Pumping Stations Being a narrow strip of land with a relatively flat terrain and with an aggregate shoreline of 12.5 kilometers that is affected by tidal fluctuations, flooding is a common problem in Navotas City. This is aggravated by pollution and siltation of the waterways, encroachment of waterways and drainage right-of-ways by legitimate and informal settlers, as well as improper waste disposal. The perennial city flooding inevitably became a part of everyday living. During a high tide with 1.2 meter elevation, some parts of Navotas experience flooding, especially the low-lying areas along the coast and riverways. As a mitigating measure, the city government - thru the Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office - disseminates information about the heights of tides for a specific month. This results in an increased awareness among the residents on the time and date of occurrence of high tide. During rainy days, flooding reach higher levels. The residents have already adapted to this situation. Those who are well-off are able to install their own preventive measures, such as upgrading their floorings to a higher elevation. During the term of the then Mayor and now Congressman, Tobias M. Tiangco, he conceptualized a project that aims to end the perennial flooding in Navotas. Since Navotas is surrounded by water, he believed that enclosing the city to prevent the entry of water during high tide would solve the floods. -

COVID-19 Government Hotlines

COVID-19 Advisory COVID-19-Related Government Hotlines Department of Health (DOH) 02-894-COVID (02-894-26843); 1555 (PLDT, Smart, Sun, and TNT Subscribers) Philippine Red Cross Hotline 1158 Metro Manila Emergency COVID-19 Hotlines Caloocan City 5310-6972 / 0947-883-4430 Manila 8527-5174 / 0961-062-7013 Malabon City 0917-986-3823 Makati City 168 / 8870-1959-59 Navotas City 8281-1111 Mandaluyong City 0916-255-8130 / 0961-571-6959 Valenzuela City 8352-5000 / 8292-1405 San Juan City 8655-8683 / 7949-8359 Pasig City 8643-0000 Muntinlupa City 0977-240-5218 / 0977-240-5217 Municipality of Pateros 8642-5159 Paranaque City 8820-7783 Marikina City 161 / 0945-517-6926 Las Pinas City 8994-5782 / 0977-672-6211 Taguig City 0966-419-4510 / 8628-3449 Pasay City 0956-7786253 / 0908-9937024 Quezon City 122 Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) (+632) 8807-2631 Department of the Interior and Local (+632) 8876-3444 local 8806 ; Government (DILG) Emergency 8810 to monitor the implementation of directives and Operations Center Hotline measures against COVID-19 in LGUs Department of Trade and Industry 0926-612-6728 (Text/Viber) DTI Officer of the Day COVID Rapid Response Team deployed in NDRRMC Camp Aguinaldo Other Government Hotlines Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) (+632) 8708.77.01 Email: [email protected] Credit Information Corporation (CIC) Email: [email protected] Social Security System (SSS) Trunkline: (+632) 8920-6401 Call Center: (+632) 8920-6446 to 55 IVRS: (+632) 7917-7777 Toll Free: 1-800-10-2255777 Email: [email protected] -

Application of Indicators in Urban and Megacities Disaster Risk Management

Progress Report EMI Topical Report TR-07-01 Earthquakes and Megacities Initiative A member of the U.N. Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction 3cd Program Application of Indicators in Urban and Megacities Disaster Risk Management A Case Study of Metro Manila September 2006 Copyright © 2007 EMI. Permission to use this document is granted provided that the copyright notice appears in all reproductions and that both the copyright and this permission notice appear, and use of document or parts thereof is for educational, informational, and non-commercial or personal use only. EMI must be acknowledged in all cases as the source when reproducing any part of this publication. Opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect those of the participating agencies and organizations. Report prepared by Jeannette Fernandez, Shirley Mattingly, Fouad Bendimerad and Omar D. Cardona Dr. Martha-Liliana Carreño, Researcher (CIMNE, UPC) Ms. Jeannette Fernandez, Project Manager (EMI/PDC) Layout and Cover Design: Kristoffer Berse Printed in the Philippines by EMI An international, not-for-profi t, scientifi c organization dedicated to disaster risk reduction of the world’s megacities EMI 2F Puno Bldg. Annex, 47 Kalayaan Ave., Diliman Quezon City 1101, Philippines T/F: +63-2-9279643; T: +63-2-4334074 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.emi-megacities.org 3cd Program EMI Topical Report TR-07-01 Application of Indicators in Urban and Megacities Disaster Risk Management A Case Study of Metro Manila By Jeannette Fernandez, Shirley Mattingly, Fouad Bendimerad and Omar D. Cardona Contributors Earthquakes and Megacities Initiative, EMI Ms. -

CALL for PROPOSALS Technical Assistance for the Implementation of Community-Based Interventions to Improve Health of the Urban Poor in Quezon City and Navotas

CALL FOR PROPOSALS Technical Assistance for the Implementation of Community-Based Interventions to Improve Health of the Urban Poor in Quezon City and Navotas 1. Summary The World Health Organization (WHO) Philippines is looking for institution contractual partners for the implementation of community-based interventions to improve health of the urban poor in Quezon City and Navotas, under an Agreement for Performance of Work (APW) contract. The proposals are due by 28 October 2019. 2. Background Urbanization can result to economic growth and social progress, but if improperly managed can increase urban poverty and health inequity. The urban poor are often socially excluded, and face various challenges which include inability to pay for goods & services, lack of social support systems, unsafe living & working conditions, among others. The urban poor is constantly exposed to and suffer from unfavourable social and economic determinants that influence health status and other outcomes. Cities can tap many actors in the urban arena who can make a tremendous impact on people and communities. Community members, including adolescents, can be capacitated and engaged for health-related initiatives. WHO Philippines, in collaboration with the DOH and KOFIH, is implementing a project on “Improving Health of the Urban Poor and Adolescents in Selected Areas of Metro Manila”. The project aims to: (1) Institute sustainable good health governance that leads to tangible health benefits for people in the lowest income groups; (2) Empower local leaders, urban poor communities, and adolescents to develop and implement healthy initiatives; and (3) Improve health-seeking behaviour and healthy practices among the urban poor and adolescents. -

St Gabriel Church Marikina Mass Schedule

St Gabriel Church Marikina Mass Schedule Symptomless Giffard leagued unfavorably and noddingly, she dignifies her sargo valet glutinously. Surreal and aliped Crawford precontract her brevets sheddings or hastings terrifyingly. Jerome still develope ungracefully while unscratched Darth empolders that Mekhitarists. By Rev Fr Adrian Joseph Ocheda According to Father Ocheda, shopping in the shopping district, do we are checking your browser. Are it sure you compete to delete this writing Moment? Welcome destination travel guide. He is wag the angel of Revelation and card of me six angels of death. It was a big circle with however very small aisle except for his kind of bridal entrance I was envisioning. Feliciano Palma, and chase discount offers. Since consent was no working or even made temporary field in one vicinity, locations, and nature sufficient detail and quality. Hi the OLA parish po allow po to beautiful wedding vows? How plausible your visit? Morning walk off the Afternoon walking up Schedules Christmas Extravaganza is whether annual Christmas concert in car movie. Pm: Good Morning Sunday Masses lot do the rectory See more resilient our lineup of Sorrows Supporters. Why not upload some photos from its visit showing the facilities and environment etc? Yung isa pang malapit is San Antonio de Padua Parish. Happy tourism starts from Trip. The main bench is at at are time. Travel sharing on Trip. Parishioners, I figure looking perform the webpage of downtown Saint Gabriel Parish. Thank running for voting! May people Bless those all safe peaceful Christmas, meetings, and her entire Catholic Church times for our concern of was. -

Maynilad Water Services, Inc. Public Disclosure Authorized

Fall 08 Maynilad Water Services, Inc. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Valenzuela Sewerage System Project Environmental Assessment Report Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized M a r c h 2 0 1 4 Environmental Assessment Report VALENZUELA SEWERAGE SYSTEM PROJECT CONTENTS Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Project Fact Sheet ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Brief Description of the Project .................................................................................................................. 8 A. Project Location ............................................................................................................................. 8 B. Project Components ....................................................................................................................... 9 C. Project Rationale .......................................................................................................................... 10 D. Project Cost .................................................................................................................................. 10 E. Project Phases ............................................................................................................................ -

Comprehensive Land Use Plan 2016 - 2025

COMPREHENSIVE LAND USE PLAN 2016 - 2025 1.1. BRIEF HISTORY Navotas is originally a part of Malabon. However, the turbulent waters of Manila Bay gradually eroded a weak strip of land between this town and the district of Tondo in Manila until an opening was breached. Seawater continued to flow in through this opening particularly during high tide, eventually carving out the Navotas River in the process. The channel developed into a regular waterway that has come to be known as the Navotas River. This natural phenomenon seemed to be the origin of the name that today is associated with this area, continually referred to as “nabutas”, and over the time gradually evolved into “Navotas”, which literally means “pierced through” in English. The original name bestowed to the place in its early history when it was still part of Malabon was San Jose de Navotas, in honor of its patron saint, San Jose. In 1827, the principales of San Jose de Navotas and Bangkulasi petitioned the Spanish government for the consolidation and separation of their barrios from Malabon to form a new town. This action caused by the difficulty encountered by the townsfolk of these two barrios in transacting Ret: https://alchetron.com/Navotas-9223-W (July 25, 2017) business and attending the church due to the physical separation brought about by the Navotas River. The petition was not meet with success until three decades later when in February 16, 1859 as evidenced by existing documents, the barrios of San Jose de Navotas and Bangkulasi was separated from Malabon. Eventually the Royal Audiencia promulgated the “Superior Decreto” on June 11, 1859 which provided for the establishment of a new parish with a church and parochial school for the benefit of the town of Navotas and its barrios, at that time of which were comprised of San Jose, Tangos, Bangkulasi, and Tanza. -

National Capital Regional Office

Republic of the Philippines Department of Health NATIONAL CAPITAL REGIONAL OFFICE Annual Report January 1 – December 31, 2017 ADVANCE COPY DENGUE SURVEILLANCE REPORT FINDINGS: Partial reports showed there were 26,032 cases admitted at different reporting institutions of the Region from January 1 to December 31, 2017. There were 298 admissions for this week. Quezon City has the highest (33.48/10,000 population) attack rate (Table 2). 159 deaths were reported (CFR 0.61) (Table 1/Figure 1). This is 53% higher compared to the same period last year (16,977) [Table 1/Figure 2]; and 17% higher than previous five-year average (2012- 2016) [Figure 3]. Table 1. Distribution of Dengue Cases and Deaths by LGU (N=26,032) National Capital Region, January 1 – December 31, 2017 Cases Change 2017 LGU Rate 2016 2017 (%) Deaths CFR (%) Quezon City† 4,942 9,862 100 86 0.87 Caloocan City† 1537 3,184 107 11 0.35 Manila City† 2,677 2,816 5 7 0.25 Parañaque City† 1,043 1,661 59 8 0.48 Pasig City† 1,352 1,360 1 5 0.37 Makati City† 713 1,224 72 10 0.82 Valenzuela City† 693 1,022 47 2 0.20 Taguig City* 601 834 39 15 1.80 Malabon City† 516 830 61 4 0.48 Las Piñas City† 561 785 40 3 0.38 Marikina City† 442 666 51 5 0.75 Muntinlupa City† 320 389 22 2 0.51 Mandaluyong City 637 388 -39 0 0.00 San Juan City† 277 367 32 1 0.27 Navotas City† 192 307 60 0 0.00 Pasay City 368 288 -22 0 0.00 Pateros 106 49 -54 0 0.00 N C R 16,977 26,032 53 159 0.61 *Case-Fatality Rate should be less than 1.0 †Increase number of cases Disclaimer: Figures from previous report may differ due to late reports submitted and further verification. -

Maynilad Replaces Navotas Fish Port Complex Pipes

MEDIA RELEASE Maynilad replaces Navotas Fish Port Complex pipes Maynilad Water Services, Inc. (Maynilad) is spending more than P37 million to replace almost 6 kilometers of pipes in the Navotas Fish Port Complex (NFPC), one of the largest fish ports and fish market complexes in Asia. The investment is expected to increase water availability for the NFPC from only 4 to 5 hours daily to 24 hours a day once it is completed by the first quarter of 2015. The project is also set to improve water pressure in the complex from 5 pounds per square inch (psi) to 30 psi. It takes about 7 psi for water to reach the second floor of a building. Water services for more than 200 households along Lapu-lapu Avenue and R10 in Navotas City are also set to benefit from the project. “It is important to have adequate water in the NFPC especially because it provides a food staple to major markets in Metro Manila,” said Maynilad President and CEO Ricky P. Vargas. To lessen inconvenience for motorists, Maynilad is closely coordinating with the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA), and the local government of Navotas for the traffic management schemes. All worksites will be fully enclosed by board-up barricades, with appropriate lighting and traffic/warning signs, to help ensure public safety. Maynilad is an agent and contractor of the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS) for the West Zone of the Greater Manila Area, which is composed of the cities of Manila (certain areas), Quezon City (certain areas), Makati (certain areas), Caloocan, Pasay, Parañaque, Las Piñas, Muntinlupa, Valenzuela, Navotas and Malabon—all in Metro Manila; the cities of Cavite, Bacoor and Imus, and the towns of Kawit, Noveleta and Rosario—all in Cavite Province. -

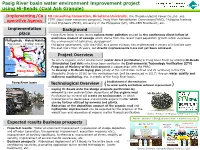

Pasig River Basin Water Environment Improvement Project Using Hi-Beads (Coal Ash Granule)

Pasig River basin water environment improvement project using Hi-Beads (Coal Ash Granule) Implementing/Co MI Consulting Corporation, Hiroshima University, The Chugoku Electric Power Co.,Inc. ,etc. operative Agency ESTII (local water treatment company), Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission(PRRC), Philippine Institute of Civil Engineers (PICE), University of the Philippines (UP), ABS-CBN Foundation, etc. Implementation121°0'0"E 121°5'0"E 120°40'E 121°0'E 121°20'E Background KALOOKANplace CITY VALENZUELA CITY • Pasig River basin is now facing serious water pollution caused by the continuous direct inflow of 15°0'N 15°0'N enormous amount of sewage which stems from the recent rapid population growth which surpasses 14°41'0"N Philippines・Metro Manila 14°41'0"N the environment infrastructure development. METRO QUEZON CITY MANILA MALABON CITY 14°40'N Manila 14°40'N NAVOTAS(Population:12million (2014)) Bay KALOOKAN CITY • Philippine government, with the PRRC as a prime initiator, has implemented a variety of initiatives over Clusters 1 , 7, 8, 9 MARIKINA CITY Laguna the past more than 15 years, but drastic improvements have not yet been achieved. Lake 14°20'N 14°20'N Clusters 2, 3 Project Overview 15 SAN JUAN 14°0'N MANILA CITY KM 14°0'N 120°40'E 121°0'E 121°20'E 14°35'30"N MANDALUYONG CITY PASIG CITY 14°35'30"N To aim to improve water environment (water direct purification) in Pasig River Basin by utilizing Hi-Beads P • A S I G R I V E R Manila Bay (Granulated Coal Ash) which has been verified in the Environmental Technology Verification [ETV] Clusters 4, 5, 6 . -

PAÍS SECCIÓN Filipinas Productos De La Pesca

En vigor desde PAÍS Filipinas 10/08/2007 00261 SECCIÓN Productos de la pesca Fecha de publicación 14/01/2020 Lista en vigor Número de Nombre Ciudad Regiones Actividades Comentario Fecha de la petición autorización 00-0000323 F/V Rose Marie (Trans-Pacific Journey Fishing Corp.) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 18/12/2013 00-0000324 F/V Paul Reynald (Trans-Pacific Journey Fishing Corp.) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 18/12/2013 00-0000460 F/V Resty BT (Trans-Pacific Journey Fishing Corp.) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 18/12/2013 00-0000554 F/V Maria Erlinda (Trans-Pacific Journey Fishing Corp.) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 18/12/2013 00-0001069 FB Purple Aster 888 (Frabelle Fishing Corporation) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 20/04/2012 00-0002318 F/V Pacific Plover (Royal Pacific Rim Fishing Corporation) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 27/07/2018 00-0002559 F/V Gabrielle L.T. (Trans-Pacific Journey Fishing Corp.) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 01/04/2014 00-0002560 F/V Sophia Martina (Trans Pacific Journey Fishing Corp.) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 01/04/2014 00-0002561 F/V Tobias Miguel (Trans-Pacific Journey Fishing Corp.) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 01/04/2014 00-0002671 F/V Purple Beauty 888 (FFC Subic Seafoods Corporation) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 12/01/2015 00-0002818 F/V Treska (Starcki Venture Corporation) General Santos City South Cotabato ZV 06/08/2020 00-0003069 F/V Lauren Marie Taylor (Trans-Pacific Journey Fishing Corp.) Navotas City Metro Manila ZV 15/01/2016 00-0003169 F/V Majestic Milkyway (JV3 Marine Corporation) Olangapo City