The Emigrants from Småland, Sweden. the American Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Immigrant in Fiction

THE AMERICAN IMMIGRANT IN FICTION by Gayle Venable Hieke Submitted as an Honors Paper in the Department of History Woman's College of the University of North Carolina Greensboro 1963 Approve^ by %4y^ Wsjdr&l Director Examining Committee c«-i 'i-a-.c- &Mrt--l ■-*-*- gjjfa U- A/y^t^C TABLE OP CONTENTS Part I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. IMMIGRANT EXPRESSION THROUGH NONPICTION 4 III. AUTHORS OP IMMIGRANT FICTION 10 IV. MOTIVES FOR CREATING IMMIGRANT FICTION 22 V. LITERARY TECHNIQUES IN IMMIGRANT FICTION 35 VI. RECURRENT THEMES IN IMMIGRANT FICTION 38 VII. CONCLUSION 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY INTRODUCTION People streamed from Europe driven to a new land by the lack of food and the lack of land, by the presence of peasant fears and the presence of racial and religious persecution, by the love of adventure and a plan for a richer life, by the hope for a more generous future and the dread of a continued oppression. It is conceded that most who wanted to come were poor or despairing, harrassed or discontented, but only the courageous and optimistic dared to come. Many others who chose to migrate could have continued to lead comfortable lives in Europe, but curiosity about America and confidence in its future influenced them to transfer. Only the bold and enterprising have sufficient courage: they are the Instruments which stir up the tranquil hamlete and shake the order of unchangeableness. These separate from the multitude and fill a few small ships a trickle here and there starts the running stream which in due time swells to a mighty river.1 The crossing was often marked by diseases of body and mind, by deprivation of needs, physical and spiritual, and by humiliation of landsmen on the sea and Individuals in a herd. -

Fiction of Scandinavian Women and the American Prairie

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2012 No Place Like Home: Fiction of Scandinavian Women and the American Prairie Rebecca Frances Crockett [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation Crockett, Rebecca Frances, "No Place Like Home: Fiction of Scandinavian Women and the American Prairie. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1144 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Rebecca Frances Crockett entitled "No Place Like Home: Fiction of Scandinavian Women and the American Prairie." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Mary E. Papke, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Charles Maland, William Hardwig Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) No Place Like Home: Fiction of Scandinavian Women and the American Prairie A Thesis Presented for The Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Rebecca Frances Crockett May 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Rebecca Frances Crockett i Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Doug and Patricia Crockett, who taught me early the value of good books. -

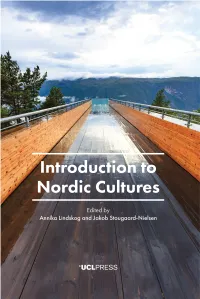

Introduction-To-Nordic-Cultures.Pdf

Introduction to Nordic Cultures Introduction to Nordic Cultures Edited by Annika Lindskog and Jakob Stougaard-Nielsen First published in 2020 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Text © Contributors, 2020 Images © Copyright holders named in captions, 2020 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0). This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Lindskog, A. and Stougaard-Nielsen, J. (eds.). 2020. Introduction to Nordic Cultures. London: UCL Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787353992 Further details about Creative Commons licences are available at http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons licence unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. If you would like to reuse any third-party material not covered by the book’s Creative Commons licence, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. ISBN: 978-1-78735-401-2 (Hbk.) ISBN: 978-1-78735-400-5 (Pbk.) ISBN: 978-1-78735-399-2 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-78735-402-9 (epub) ISBN: 978-1-78735-403-6 (mobi) DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787353992 Contents List of figures vii List of contributors x Acknowledgements xiii Editorial Introduction to Nordic Cultures 1 Annika Lindskog and Jakob Stougaard-Nielsen Part I: Identities 9 1. -

The Emigrants Series Book Club RSVP Greatly Appreciated but Not

February 29, 2016 For immediate release Contact: Heidi Gould Education Coordinator, Carver County Historical Society (952) 442-4234; [email protected] The Emigrants Series Book Club Local Swedish farmer Andrew Peterson kept a daily diary from the time he left Sweden to about 2 days before his death. This 50+ year diary provides a wonderful insight into the lives of early pioneer farmers. Upon his death, Peterson’s children donated this diary to the Minnesota Historical Society. In the 1940’s, Swedish novelist Vilhelm Moberg discovered the diary there, and used the information contained in it as the basis for a series of novels– The Emigrants (1949), Unto a Good Land (1952), The Settlers (1956) and The Last Letter Home (1959). The novels were published in English in 1951, 1954, and 1961, respectively. Two films, The Emigrants and The New Land were made from these books in the 1970’s. Join us as we explore these books, and the worlds of protagonists Karl Oskar and Kristina. Discover connections to Andrew Peterson as we explore one book a month. RSVP greatly appreciated but not required. Dates: Saturdays– April 23, May 28, June 25, July 23 Times: 10am-12pm Cost: FREE Books available through the CCHS. Copies also available through Carver County libraries. **Get your books and start reading- book club starts in just under two months!** About the Carver County Historical Society Established in 1940, the Carver County Historical Society is a private, not-for-profit organization whose mission is to collect, preserve and interpret the history of Carver County. -

The Art of Translation a Study of Book Titles Translated from English Into Swedish and from Swedish Into English

Estetisk-filosofiska fakulteten Anna Gavling The art of translation A study of book titles translated from English into Swedish and from Swedish into English Engelska C-uppsats Termin: Vårterminen 2008 Handledare: Michael Wherrity Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se Titel: The art of translation, A study of the translation of book titles from English into Swedish and Swedish into English Författare: Gavling, Anna English III, 2008 Antal sidor: 46 Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to investigate the process of translating a book title from English into Swedish and vice versa. I have investigated the different methods used when translating a title, as well how common each strategy is. By contacting publishing companies and translators in Sweden, I learned of the process of adapting a title from the source language into a foreign market and the target language. Studying 156 titles originally published in English, and 47 titles originally written in Swedish, I was able to see some patterns. I was particularly interested in what strategies are most commonly used. In my study I found nine different strategies of translating a book title form English into Swedish. I have classified them as follows: Keeping the original title, Translating the title literally, Literal translation with modifications, Keeping part of the original title and adding a literal translation, Adding a Swedish tag to the English title, Adding a Swedish tag to the literal translation, Translation with an omission, Creating a new title loosely related to the original title and finally Creating a completely different title. -

Swedish American Genealogy and Local History: Selected Titles at the Library of Congress

SWEDISH AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND LOCAL HISTORY: SELECTED TITLES AT THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled and Annotated by Lee V. Douglas CONTENTS I.. Introduction . 1 II. General Works on Scandinavian Emigration . 3 III. Memoirs, Registers of Names, Passenger Lists, . 5 Essays on Sweden and Swedish America IV. Handbooks on Methodology of Swedish and . 23 Swedish-American Genealogical Research V. Local Histories in the United Sates California . 28 Idaho . 29 Illinois . 30 Iowa . 32 Kansas . 32 Maine . 34 Minnesota . 35 New Jersey . 38 New York . 39 South Dakota . 40 Texas . 40 Wisconsin . 41 VI. Personal Names . 42 I. INTRODUCTION Swedish American studies, including local history and genealogy, are among the best documented immigrant studies in the United States. This is the result of the Swedish genius for documenting almost every aspect of life from birth to death. They have, in fact, created and retained documents that Americans would never think of looking for, such as certificates of change of employment, of change of address, military records relating whether a soldier's horse was properly equipped, and more common events such as marriage, emigration, and death. When immigrants arrived in the United States and found that they were not bound to the single state religion into which they had been born, the Swedish church split into many denominations that emphasized one or another aspect of religion and culture. Some required children to study the mother tongue in Saturday classes, others did not. Some, more liberal than European Swedish Lutheranism, permitted freedom of religion in the new country and even allowed sects to flourish that had been banned in Sweden. -

Litteratur (Eng)

swedishPublished culture by the Swedish Institute August 2004 FS 114 c Modern Literature A whole century of Swedish literature necessarily encompasses numerous literary currents: folk romanticism, fl âneur literature, expressionism, bourgeois novels, surrealistic poetry, urbane portraits, social criticism, social realism, and accounts of the disintegration of the welfare state and the fragility of the individual. Some writers belonging to this literary scene have only one role to play, but a major one. Others reappear in several guises. Different voices from different epochs speak to us, loudly or softly, from “their” particular Sweden. 2 SWEDISH CULTURE MODERN LITERATURE TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY CURRENTS Hjalmar Bergman (1883–1931), one of Another social rebel was Ivar Lo- Two giants dominated Swedish literature the truly great storytellers of Swedish lit- Johansson (1901–1990) who became the at the turn of the 20th century: Selma La- erature, was both a novelist and a drama- dominant fi gure among Swedish proletari- gerlöf (1858–1940) and August Strindberg tist. One of his specialties was portraying an writers. He portrayed the cotters — poor (1849–1912), whose infl uence on narrative the evils of contemporary life in a carniva- farm laborers who were paid mainly in kind and drama has been felt ever since. Strind- lesque, entertaining way, as in his 1919 nov- — in such novels as Godnatt, jord (Break- berg’s Röda Rummet (The Red Room), 1879, el about small-town life, Markurells i Wad- ing Free), 1933, and he captured the big-city and Lagerlöf’s Gösta Berlings saga (Gösta köping (God’s Orchid). Farmor och vår herre mentality in novels like Kungsgatan (King’s Berling’s Saga), 1891, are considered the fi rst (Thy Rod and Thy Staff), 1921, and Clownen Street), 1935. -

Emigration and Literature: Vilhelm Moberg

EMIGRATION AND LITERATURE: VILHELM MOBERG Peter Graves Vilhelm Moberg (1898-1973) was the first Swedish writer of fiction to take up the great migrations to North America during the 19th century as a literary theme. He was the son of a soldier-crofter under the old military system whereby Sweden supported its reserve army through each parish having the duty to provide a soldier by making available a croft on which he could work and support his family. The emigration was, so to speak, there in Moberg's background long before it became a source of literary inspiration to him. His home province - Smaland in southern Sweden - consistently stood top of the league table of provinces that sent their sons and daughters out on the emigrant trail to a hoped-for better life. Throughout the period 1850-1930 Smaland was dispatching an annual average of 4.6 emigrants per thousand inhabitants, and in the 1880s that figure peaked at about 11 per thousand. The only province to exceed it in both respects was Halland - the province that borders it to the south-west. And if this particular provincial background predisposed Moberg to take up the theme ofemigration so equally did his family background. In an autobiographical article in 1957 he wrote: 'On the soldier croft where I was born and grew up they talked every day about the country where my parents' brothers and sisters lived. I remember the word America right from the earliest stage in my child hood when I first began to understand words.' On both maternal and paternal sides of his family almost all his aunts and uncles were in America, and in the same biographical anecdote he tells us: 'For a long time I thought that cousins were a sort of posh upper-class children only to be found in America.' He himself was due to join these transatlantic cousins as a 16 year old in 1914, but the remaining family at home - his mother in particular - pleaded with him to stay. -

Full Issue Vol. 22 No. 2

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 22 Number 2 Article 1 6-1-2002 Full Issue Vol. 22 No. 2 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation (2002) "Full Issue Vol. 22 No. 2," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol22/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (ISSN 0275-9314) ' Swedish American Genealo ist A journal devoted to Swedish American biography, genealogy and personal history CONTENTS America in My Childhood by Ulf Beijbom 57 Vilhelm Moberg's Relatives-Morbroder, Moster, and Syster-in the United States by James E. Erickson 64 The Memoirs of My Uncle Peter Jacob Aronson by Vilhelm Moberg; translated by Ingrid A. Lang; introduced by Ingrid Nettervik; annotated by James E. Erickson 76 The Story About the Mistelas Murder by Elisabeth Anderberg 96 Genealogical Workshop: Emigration and Immigration Records by Jill Seaholm 98 Genealogical Queries 108 Twelfth Annual SAG Workshop, Salt Lake City 112 Vol. XXII June 2002 No. 2 Swedish American ist� :alog �,�� (ISSN 0275-9314) • Swedish American Genealogist- Publisher: Swenson Swedish ImmigraLion Research Center Augus�ana College Rock Island, IL 6 201-2296 Telephone: 309-794-7204 Fax: -309-794-7443 E-mail: [email protected] Web address: http://www.augustana.edu/adrninistration/swenson/ Editor: James E. -

Mobergland. Personligt Och Politiskt I Vilhelm Mobergs Utvandrarserie

Mobergland. Personligt och politiskt i Vilhelm Mobergs utvandrarserie. Liljestrand, Jens 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Liljestrand, J. (2009). Mobergland. Personligt och politiskt i Vilhelm Mobergs utvandrarserie. Ordfront förlag. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 mobergland av jens liljestrand har tidigare utgivits: Made in Pride, Timbro 2003 Vi äro svenska scouter vi, Atlas 2004 Om Gud vill och hälsan varar: Vilhelm Mobergs brev 1918–1949 (red.), Carlsson 2007 Paris–Dakar, Ordfront 2008 Du tror väl att jag är död: Vilhelm Mobergs brev 1950–1973 (red.), Carlsson 2008 Det här är en bok från Ordfront Ordfront är en oberoende kulturförening som verkar för demokrati, mänskliga rättigheter och yttrandefrihet. -

Prairie Forum

PRAIRIE FORUM Vol. 13, NO.1 Spring 1988 CONTENTS ARTICLES Visual Depictions of Upper Fort Garry Brad Loewen and Gregory G. Monks The Indian Pass System in the Canadian West, 1882-1935 F. Laurie Barron 25 Changing Farm Size Distribution on the Prairies Over the Past One Hundred Years Ray D. Bollman and Philip Ehrensaft 43 Winning the West: R.B. Bennett and the Conservative Breakthrough on the Prairies, 1927-1930 Larry A. Glassford 67 Literature as Social History: A Swedish Novelist in Manitoba L. Anders Sandberg 83 Soil Conservation: The Barriers to Comprehensive National Response Edward W. Manning 99 BOOK REVIEWS MacEWAN, Grant, Frederick Haultain: Frontier Statesman of the Canadian Northwest by George Hoffman 123 FRANKS, C.E.S., Public Administration Questions Relating to Aboriginal Self-Government; COWIE, Ian B., Future Issues between Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Governments; OPEKOKEW, Delia, The Political and Legal Inequities Among Aboriginal Peoples in Canada; PETERS, Evelyn J., Aboriginal Self-Government in Canada: A Bibliography 1986 by W.H. McConnell 125 KINNEAR, Mary and FAST, Vera, Planting the Garden: An Annotated Archival Bibliography of the History of Women in Manitoba; KINNEAR, Mary (editor), First Days, Fighting Days: Women in Manitoba History by Ann Leger Anderson 127 JOHNSTON, Alex, Plants and the Blackfoot by Murray G. Maw 132 McLEOD, Thomas H. and McLEOD, lan, Tommy Douglas: The Road to Jerusalem by James N. McCrorie 133 NUFFIELD, E.W., With the West in Her Eyes: Nellie Hislop's Story by Mary Kinnear 138 TITLEY, E. Brian, A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada by Sarah Carter 139 MISKA, John P., Canadian Studies on Hungarians, 1886-1986: An Annotated Bibliography of Primary and Secondaly Sources by Christopher D. -

Fiction As Interpretation of the Emigrant Experience: the Novels of Johan Bojer, O.E

American Studies in Scandinavia, Vol. 18, 1986: 83-92 Fiction as Interpretation of the Emigrant Experience: The Novels of Johan Bojer, O.E. Rdvaag, Vilhelm Moberg and Alfred Hauge* By Ingeborg R. Kongslien University of Oslo My idea in focusing on these novels featuring the Scandinavian emigra- tion to America is the assumption that fiction can be an important factor in conveying historical knowledge and human experience. Writers of fiction can do something different from what historians can, namely dramatize and individualize man's meeting with the historical condi- tions. The selected novels are called "emigrant novels" due to the material with which they deal, namely the Norwegian and Swedish emigration to the United States in the previous century, and due to the thematic struc- ture that we find in these works, a structure which in fact embodies the entire emigration process. The novels that will be the focus of this paper are the Norwegian Johan Bojer's Vor egen stamme (1924)' translated into English as The Emigrants; the Norwegian-American O.E. Rdvaag's I de dage (1924), and Riket grundlqges (1925)' both volumes in English as Giants in the Earth, and the sequels Peder Seier and Den signede dug, translated into English as Peder Victorious and Their Fathers' God respectively; the Swedish Vilhelm Moberg's Utvandrarna (1949), Inuandrarna (1952)' Nybggarna (1956) and Sista brevet tillSuerige (1959), in English as The Emigrants, Unto a Good Land, The Settlers and Last Letter Home; and the Norwegian Alfred Hauge's Cleng Peerson: Hundevakt (1961), Cleng Peerson: Landkjenning (1964), and Cleng Peerson: Ankerfeste (1965)' translated into English in two volumes as Cleng Peerson I and II.