The Beta Israel and Their Experience of Multiple Diasporas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Everyday Geopolitics of Messianic Jews in Israel-Palestine

Title Page The everyday geopolitics of Messianic Jews in Israel-Palestine. Daniel Webb Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London. Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD, University of London, 2015. 1 Declaration I Daniel Webb hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Date: Sign: 2 Abstract This thesis examines the geopolitical orientations of Messianic Jews in Jerusalem, Israel-Palestine, in order to shed light on the confluence and co-constitution of religion and geopolitics. Messianic Jews are individuals who self-identify as being ethnically Jewish, but who hold beliefs that are largely indistinguishable from Christianity. Using the prism of ‘everyday geopolitics’, I explore my informants’ encounters with, and experiences of, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the dominant geopolitical logics that underpin it. I analyse the myriad of everyday factors that were formative in the shaping of my informants’ geopolitical orientation towards the conflict, focusing chiefly on those that were mediated and embodied through religious practice and belief. The material for the research was gathered in Jerusalem over the course of sixteen months – between September 2012 and January 2014 – largely through ethnographic research methods. Accordingly, I offer a lived alternative to existing work on geopolitics and religion; work that is dominated by overly cerebral and cognitivist views of religion. By contrast, I show how the urgencies of everyday life, as well as a number of religious practices, attune Messianic Jewish geopolitical orientations in dynamic, contingent, and contradictory ways. -

Print Friendly Version

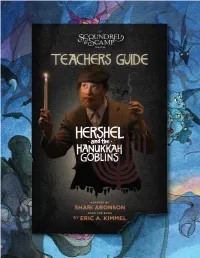

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 The Holiday of Hanukkah 5 Judaism and the Jewish Diaspora 8 Ashkenazi Jews and Yiddish 9 Latkes! 10 Pickles! 11 Body Mapping 12 Becoming the Light 13 The Nigun 14 Reflections with Playwright Shari Aronson 15 Interview with Author Eric Kimmel 17 Glossary 18 Bibliography Using the Guide Welcome, Teachers! This guide is intended as a supplement to the Scoundrel and Scamp’s production of Hershel & The Hanukkah Goblins. Please note that words bolded in the guide are vocabulary that are listed and defined at the end of the guide. 2 Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins Teachers Guide | The Scoundrel & Scamp Theatre The Holiday of Hanukkah Introduction to Hanukkah Questions: In Hebrew, the word Hanukkah means inauguration, dedication, 1. What comes to your mind first or consecration. It is a less important Jewish holiday than others, when you think about Hanukkah? but has become popular over the years because of its proximity to Christmas which has influenced some aspects of the holiday. 2. Have you ever participated in a Hanukkah tells the story of a military victory and the miracle that Hanukkah celebration? What do happened more than 2,000 years ago in the province of Judea, you remember the most about it? now known as Palestine. At that time, Jews were forced to give up the study of the Torah, their holy book, under the threat of death 3. It is traditional on Hanukkah to as their synagogues were taken over and destroyed. A group of eat cheese and foods fried in oil. fighters resisted and defeated this army, cleaned and took back Do you eat cheese or fried foods? their synagogue, and re-lit the menorah (a ceremonial lamp) with If so, what are your favorite kinds? oil that should have only lasted for one night but that lasted for eight nights instead. -

Post-Colonial Journeys: Historical Roots of Immigration Andintegration

Post-Colonial Journeys: Historical Roots of Immigration andIntegration DYLAN RILEY AND REBECCA JEAN EMIGH* ABSTRACT The effect ofItalian colonialismon migration to Italy differedaccording to the pre-colonialsocial structure, afactor previouslyneglected byimmigration theories. In Eritrea,pre- colonialChristianity, sharp class distinctions,and a strong state promotedinteraction between colonizers andcolonized. Eritrean nationalismemerged against Ethiopia; thus, nosharp breakbetween Eritreans andItalians emerged.Two outgrowths ofcolonialism, the Eritrean nationalmovement andreligious ties,facilitate immigration and integration. In contrast, in Somalia,there was nostrong state, few class differences, the dominantreligion was Islam, andnationalists opposed Italian rule.Consequently, Somali developed few institutionalties to colonialauthorities and few institutionsprovided resources to immigrants.Thus, Somaliimmigrants are few andare not well integratedinto Italian society. * Direct allcorrespondence to Rebecca Jean Emigh, Department ofSociology, 264 HainesHall, Box 951551,Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551;e-mail: [email protected]. ucla.edu.We would like to thank Caroline Brettell, RogerWaldinger, and Roy Pateman for their helpfulcomments. ChaseLangford made the map.A versionof this paperwas presentedat the Tenth International Conference ofEuropeanists,March 1996.Grants from the Center forGerman andEuropean Studies at the University ofCalifornia,Berkeley and the UCLA FacultySenate supported this research. ComparativeSociology, Volume 1,issue 2 -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

Ethnicity and Nationality Among Ethiopians in Canada's Census Data: a Consideration of Overlapping and Divergent Identities

UC Merced UC Merced Previously Published Works Title Ethnicity and nationality among Ethiopians in Canada's census data: a consideration of overlapping and divergent identities. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3pt9v7fp Journal Comparative migration studies, 6(1) ISSN 2214-594X Author Thompson, Daniel K Publication Date 2018 DOI 10.1186/s40878-018-0075-5 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Thompson Comparative Migration Studies (2018) 6:6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-018-0075-5 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Ethnicity and nationality among Ethiopians in Canada’s census data: a consideration of overlapping and divergent identities Daniel K. Thompson1,2 Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract 1 Department of Anthropology, ‘ ’ Emory University, 1557 Dickey Drive, This article addresses the intersection of homeland politics and diaspora identities Atlanta, GA 30322, USA by assessing whether geopolitical changes in Ethiopia affect ethno-national identifications 2College of Social Sciences and among Ethiopian-origin populations living abroad. Officials in Ethiopia’slargestethnically- Humanities, Jigjiga University, Jigjiga, Ethiopia defined states recently began working to improve diaspora-homeland relations, historically characterised by ethnically-mobilized support for opposition and insurgency. The emergence of an ‘Ethiopian-Somali’ identity indicated in recent research, previously regarded as a contradiction in terms, is the most striking of a series of realignments -

Ethiopians and Somalis Interviewed in Yemen

Greenland Iceland Finland Norway Sweden Estonia Latvia Denmark Lithuania Northern Ireland Canada Ireland United Belarus Kingdom Netherlands Poland Germany Belgium Czechia Ukraine Slovakia Russia Austria Switzerland Hungary Moldova France Slovenia Kazakhstan Croatia Romania Mongolia Bosnia and HerzegovinaSerbia Montenegro Bulgaria MMC East AfricaKosovo and Yemen 4Mi Snapshot - JuneGeorgia 2020 Macedonia Uzbekistan Kyrgyzstan Italy Albania Armenia Azerbaijan United States Ethiopians and Somalis Interviewed in Yemen North Portugal Greece Turkmenistan Tajikistan Korea Spain Turkey South The ‘Eastern Route’ is the mixed migration route from East Africa to the Gulf (through Overall, 60% of the respondents were from Ethiopia’s Oromia Region (n=76, 62 men and Korea Japan Yemen) and is the largest mixed migration route out of East Africa. An estimated 138,213 14Cyprus women). OromiaSyria Region is a highly populated region which hosts Ethiopia’s capital city refugees and migrants arrived in Yemen in 2019, and at least 29,643 reportedly arrived Addis Ababa.Lebanon Oromos face persecution in Ethiopia, and partner reports show that Oromos Iraq Afghanistan China Moroccobetween January and April 2020Tunisia. Ethiopians made up around 92% of the arrivals into typically make up the largest proportion of Ethiopians travelingIran through Yemen, where they Jordan Yemen in 2019 and Somalis around 8%. are particularly subject to abuse. The highest number of Somali respondents come from Israel Banadir Region (n=18), which some of the highest numbers of internally displaced people Every year, tensAlgeria of thousands of Ethiopians and Somalis travel through harsh terrain in in Africa. The capital city of Mogadishu isKuwait located in Banadir Region and areas around it Libya Egypt Nepal Djibouti and Puntland, Somalia to reach departure areas along the coastline where they host many displaced people seeking safety and jobs. -

The Role of the Ethiopian Diaspora in Ethiopia

The Role of the Ethiopian Diaspora in Ethiopia Solomon Getahun Paper presented at Ethiopia Forum: Challenges and Prospects for Constitutional Democracy in Ethiopia International Center, Michigan State University East Lansing, Michigan, March 22-24, 2019 Abstract: The Ethiopian diaspora is a post-1970s phenomenon. Ethiopian government sources has it that there are more than 3 million Ethiopians scattered throughout the world: From America to Australia, from Norway to South Africa. However, the majority of these Ethiopians reside in the US, the Arab Middle East, and Israel in that order. Currently, a little more than a quarter of a million Ethiopians live in the US. The Ethiopian diaspora in the US, like its compatriots in other parts of the world, is one of the most vocal critic of the government in Ethiopia. However, its views are as diverse as the ethnic and regional origins, manners of entry into the US, generation, and levels of education. However, the intent of this paper is not to discuss the migration history of Ethiopians but to explore some of the reasons that caused the political fallout between the various regimes in Ethiopia and the Diaspora- Ethiopians. In the meantime, the paper examines the potential and actual roles that the Ethiopian diaspora can play in Ethiopia. The Making of the Ethiopian Diaspora in the US: A Synopsis One can trace back the roots of the Ethiopian diaspora in the US to the establishment of diplomatic ties between the Government of Ethiopia and the US in 1903. In that year, the US government sent a delegation, the Skinner Mission, to Ethiopia.1 It was during this time that Menelik II, King of Kings of Ethiopia, in addition to signing trade deals with the US, expressed his interest in sending students to the United States. -

From Falashas to Ethiopian Jews

FROM FALASHAS TO ETHIOPIAN JEWS: THE EXTERNAL INFLUENCES FOR CHANGE C. 1860-1960 BY DANIEL P. SUMMERFIELD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON (SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES) FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PhD) 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673074 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673074 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The arrival of a Protestant mission in Ethiopia during the 1850s marks a turning point in the history of the Falashas. Up until this point, they lived relatively isolated in the country, unaffected and unaware of the existence of world Jewry. Following this period and especially from the beginning of the twentieth century, the attention of certain Jewish individuals and organisations was drawn to the Falashas. This contact initiated a period of external interference which would ultimately transform the Falashas, an Ethiopian phenomenon, into Ethiopian Jews, whose culture, religion and identity became increasingly connected with that of world Jewry. It is the purpose of this thesis to examine the external influences that implemented and continued the process of transformation in Falasha society which culminated in their eventual emigration to Israel. -

Eritrean Diaspora in Germany: the Case of the Eritrean Refugees in Baden-Württemberg

Eritrean Diaspora in Germany: The case of the Eritrean refugees in Baden-Württemberg Beatris de Oliveira Santos Dissertação de Mestrado em Migrações, Inter-Etnicidades e Transnacionalismo September, 2019 Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisites necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Migrações, Inter-Etnicidades e Transnacionalismo, realizada sob orientação científica da Prof. Dr. Alexandra Magnólia Dias - NOVA/FCSH e Prof. Dr. Karin Sauer - Duale Hochschule Baden-Württemberg. This dissertation is presented as a final requirement for obtaining the Master's degree in Migration, Inter-Ethnicity and Transnationalism, under the scientific guidance of Prof. Dr. Alexandra Magnólia Dias of NOVA/FCSH, and co-orientation of Prof. Dr. Karin Sauer of DHBW. Financial Support of Baden-Württemberg Stiftung ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my thesis advisors Prof. Dr. Alexandra Magnólia Dias of the New University of Lisbon and Prof. Dr. Karin Sauer of the Duale Hochschule Villingen-Schwenningen. The access to both advisors was always open whenever I ran into trouble or had a question about my research or writing. I would also like to thank the experts who were involved in the validation survey for this research project: Jasmina Brancazio, Felicia Afryie, Karin Voigt, Orland Esser, Uwe Teztel, Werner Heinz, Volker Geisler, Abraham Haile, Tekeste Baire, Semainesh Gebrey, Inge Begger, Isaac, Natnael, Maximillian Begger, Alexsander Siyum, Robel, Dawit Woldu, Herr Kreuz, Hadassa and Teclu Lebasse. Without their passionate participation and inputs, this research could not have been successfully conducted. For all refugees who shared me their experiences with generosity, trust, knowledge and time, my sincerely thank you all. -

Racial and Ethnic Discourses Within Seattle's Habesha Community

Re-Imagining Identities: Racial and Ethnic Discourses within Seattle’s Habesha Community Azeb Madebo Abstract My research explores the means by which identities of “non- white” Habesha (Ethiopian and Eritrean) immigrants are negotiated through the use of media, community spaces, collectivism, and activism. As subjects who do not have a longstanding historical past in the United States, Ethiopian/Eritrean immigrants face the challenges of having to re-construct and negotiate their identities within American binary Black/White racial landscapes. To explore the ways in which ethnicity- based collectivism and activism challenge stereotypical portrayals of Habeshaness and Blackness which are typically cemented through media, I focus on unpacking mediated representations of Hana Alemu Williams, her death, trial, and subsequent support from the Ethiopian Community of Seattle (ECS). Hana Alemu Williams was an Ethiopian child who died in 2011 from abuse, severe malnutrition, and cruelty at the hands of her White adoptive family in Sedro-Woolley Washington. Through close readings of various media: news paper articles, television news broadcastings, and blogs, I critically analyze the moments in which Habesha immigrants challenge narratives of race and identity in the American context. I find that while Ethiopian/Eritrean immigrants sometimes assimilate into American constructions of race, at other moments they create counter-narratives of hybridity, exclusive ethnic identities, or maintain purely national identities as Ethiopian and Eritrean immigrants, in an effort to defer perceived racial stereotypes and oppression that arise from identifying with an undifferentiated Black identity. This research enriches existing academic literature by creating a more nuanced understanding of Seattle Habesha community racial and ethnic discourses in their efforts to re-imagine Habesha identities. -

Max-Planck-Institut Für Ethnologische Forschung Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology

Max-Planck-Institut für ethnologische Forschung Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology International Workshop INTEGRATION AND CONFLICT AMONG THE AFRICAN DIASPORA IN THE ORIENT November 8th – 9th 2007 Organiser: Ababu Minda Yimene Venue: Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle/S., Germany OUTLINE The Siddi are Indians of African origin, whose ancestors arrived in India beginning in the first century A.D. as sailors, domestic servants, serviles, soldiers, free adventurers and merchants. From the 13th to the 17th century India saw a large influx of Siddis as more African personnel were needed for the armies of the rising and expanding Moslem kingdoms of India. Not seldomly did Siddis rise to prominence, attaining military and governmental leadership positions. In fact, some established their own kingdoms, whose dynasties lasted even into the British rule of India. Two cases in point are the State of Habshan in Janjira and the State of Sachin. Siddis have adopted the indigenous religions (most Siddis are Muslim), food, and customs of India, though remnants of their African heritage are retained in their music. Since the Police Action of 1949-51, the armies of India’s princely states were dissolved and power was taken over by the Indian Union Army. The soldiers, including the Siddi, were retired with pensions, a drastic change for which they were ill-prepared. Moreover, as India vigorously strived to join the ranks of industrialised nations, the urban economy was subsequently transformed and the living standard of Siddis stagnated for lack of modern education and marketable skills. The identity of the Siddis has been changing since their arrival in India and especially so since India’s independence which led to the dissolution of the princely states. -

Ethiopian Jews in Canada: a Process of Constructing an Identity

Ethiopian Jews in Canada: A Process of Constructing an Identity Esther Grunau Department of Anthropology McGill University, Montreal c November, 1995 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts, Anthropology. © Esther Grunau, 1995 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ll Abstract IV Chapter 1 : Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Historical Background 17 Chapter 3: Emigration out ofEthiopia 32 Chapter 4: The Construction of Group Identity in Israel 46 Chapter 5: The Canadian Experience 70 Conclusion Ill Appendix A: Maps 113 Appendix B: Ethiopian Jewish Informants 115 Appendix C: Glossary 118 Appendix D: Abbreviations 120 References Cited 121 11 Acknowledgments This thesis could not have been completed without the support and assistance of several individuals and organizations. My supervisor, Professor Allan Young, encouraged me throughout the M.A. program and my thesis to push myself intellectually and creatively. I thank him for his gu~dance, constructive comments and support through my progression in the program and the evolution of my thesis. Professor Ell en Corin carefully supervised a readings course on Ethiopian Jews and identity which served as the background for this thesis. Throughout my progression in the course and in the M. A. program she was always available to discuss ideas with me, and her invaluable comments and support helped me to gain focus and direction in my work. Dr. Laurence Kirmayer provided me with a forum to explore the direction of my thesis through my involvement in the Culture and Mental Health Team. His insightful comments on how to link cultural anthropology with mental health challenged me to think more clearly about my graduate work and my career.