Affirmative Gatekeeping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Ridings That Will Decide Election

20 août 2018 – Telegraph Journal 5 RIDINGS THAT WILL DECIDE ELECTION ADAM HURAS LEGISLATURE BUREAU They are the ridings that the experts believe will decide the provincial election. “Depending on what happens in about five ridings, it will be a Progressive Conservative or Liberal government,” Roger Ouellette, political science professor l’Université de Moncton said in an interview. J.P. Lewis, associate professor of politics at the University of New Brunswick added: “It feels like the most likely scenario is a close seat count.” Brunswick News asked five political watchers for the five ridings to watch over the next month leading up to the Sept. 24 vote. By no means was there a consensus. There were 14 different ridings that at least one expert included in their top five list of battlegrounds that could go one way or another. “Right now, based on the regional trends, it’s really hard to call,” MQO Research polling firm vice president Stephen Moore said. Six ridings received multiple votes. The list is heavy with Moncton and Fredericton ridings. 20 août 2018 – Telegraph Journal Meanwhile, a Saint John riding and another in the province’s northeast were cited the most as runoffs that could make or break the election for the Liberals or the Progressive Conservatives. Gabriel Arsenault, political science professor at l’Université de Moncton 1. Saint John Harbour: “It was tight last time and (incumbent MLA Ed) Doherty screwed up, so I’m putting my bets on the Tories,” Arsenault said. The Progressive Conservatives called on Doherty, the former minister in charge of Service New Brunswick, to resign amid last year’s property tax assessment fiasco. -

Seating Arrangement Plan De La Chambre

Pages Sergeant-at-Arms Daniel Guitard Daniel Guitard Pages Gilles Côté Speaker Président sergent d’armes Restigouche-Chaleur Restigouche-Chaleur Seating Arrangement Plan de la Chambre Ross Wetmore Sherry Wilson Guy Arseneault Bruce Northrup Trevor Holder Gagetown- Moncton Southwest Campbellton- Sussex-Fundy- Portland-Simonds St. Martins Petitcodiac Moncton-Sud-Ouest Dalhousie Jacques LeBlanc Benoît Bourque Mary Wilson Glen Savoie Roger Melanson Shediac- Stewart Fairgrieve Hugh Flemming Kent South Oromocto-Lincoln- Saint John East Dieppe Beaubassin- Carleton Rothesay Kent-Sud Fredericton Saint John-Est Cap-Pelé Denis Landry Andrea Anderson- Bathurst East- Francine Landry Madawaska Les Jeff Carr Mason Nepisiguit- Keith Chiasson Gary Crossman Blaine Higgs Lacs-Edmundston New Maryland- Fundy-The Isles- Saint-Isidore Tracadie-Sheila Hampton Quispamsis Madawaska-Les-Lacs Sunbury Saint John West Bathurst-Est-Nepisiguit- Fundy-Les-Îles- Saint-Isidore Edmundston Saint John-Ouest Stephen Horsman Ernie Steeves Cathy Rogers Isabelle Thériault Donald J. Forestell Fredericton North Mike Holland Bruce Fitch Moncton Moncton South Caraquet Clerk Moncton-Sud Fredericton-Nord Albert Riverview Northwest greffier Moncton-Nord- Shayne Davies Gilles LePage Jake Stewart Dorothy Deputy Clerk Andrew Harvey Gerry Lowe Southwest Miramichi- Shephard sous-greffier Carleton-Victoria Restigouche West Carl Urquhart Restigouche-Ouest Saint John Harbour Carleton-York Bay du Vin Saint John Miramichi-Sud-Ouest- Lancaster Baie-du-Vin John-Patrick McCleave Clerk Assitant Lisa -

Unaudited Supplementary Employee Lists Listes D'employés

Listes d’employés Unaudited Supplementary Employee Lists supplémentaires non vérifiées The Office of the Comptroller publishes the following Le Bureau du contrôleur publie les listes supplémentaires supplementary lists: suivantes: 1. Employee salaries including Ministerial remuneration, 1. Traitements des employés, y compris la rémunération retirement allowance / severance payments, travel and des ministres, les allocations de retraite / indemnités de other expenses for each government department. cessation d’emploi, les frais de déplacement et autres 2. Employee salaries and retirement allowance / severance dépenses pour chacun des ministères. payments for government Crown Corporations, and other 2. Traitements des employés et allocations de retraite / government organizations. indemnités de cessation d’emploi des sociétés de la 3. Payments attributed to medical practitioners. Couronne et autres organismes gouvernementaux. 4. Combined supplier & grant payments and payments 3. Paiements attribués aux médecins. through purchase cards, including payments made by all 4. Paiements aux fournisseurs et subventions combinés et departments and some government organizations. paiements au titre des cartes d’achat, y compris les 5. Supplier & grant payments, loan disbursements and paiements effectués par tous les ministères et par payments through purchase cards for each department. certains organismes gouvernementaux. 5. Paiements aux fournisseurs et paiements des subventions, versements de prêts et paiements au titre des cartes d'achat pour chacun des ministères. The employee lists (1. and 2.) are located below. Salary Les listes relatives aux employés (1. et 2.) sont affichées ci- disclosure is based on the calendar year ending December 31, dessous. Les traitements sont présentés en fonction de 2018, while disclosure of car allowances, travel and other l’année civile terminée le 31 décembre 2018, alors que les expenses for departments are for the fiscal year ending allocations d’automobile, les frais de déplacement et autres March 31, 2019. -

Electoral Districts of New Brunswick Circonscriptions Électorales Du Nouveau-Brunswick

ELECTORAL DISTRICTS OF NEW BRUNSWICK CIRCONSCRIPTIONS ÉLECTORALES DU NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK 3-Restigouche-Chaleur Daniel Guitard (L) 2 -Campbellton-Dalhousie 4-Bathurst West-Beresford 5-Bathurst East-Nepisiguit-Saint-Isidore Guy Arseneault (L) Bathurst-Ouest-Beresford Bathurst-Est-Nepisiguit-Saint-Isidore Campbellton Brian Kenny (L) Denis Landry (L) 6-Caraquet Isabelle Thériault (L) 1 -Restigouche West Bathurst 49-Madawaska Les Lacs-Edmundston Restigouche-Ouest Gilles Lepage (L) 7-Shippagan-Lamèque-Miscou Madawaska-Les-Lacs-Edmundston Robert Gauvin (PC) Francine Landry (L) Edmunston ³² 8-Tracadie-Sheila Keith Chiasson (L) 47-Victoria-La Vallée 9-Miramichi Bay-Neguac Victoria-La-Vallée Baie-de-Miramichi-Neguac 48-Edmundston- Chuck Chiasson (L) 10 -Miramichi Lisa Harris (L) Michelle Conroy Madawaska Centre (PANB/AGNB) Edmundston- Miramichi Madawaska-Centre Jean-Claude (JC) D'Amours (L) Fredericton 11 -Southwest Miramichi-Bay du Vin ³² 46-Carleton-Victoria 12-Kent North Andrew Harvey (L) Miramichi-Sud-Ouest-Baie-du-Vin Jake Stewart (PC) Kent-Nord Kevin Arseneau (PVNBGP) 14-Shediac Bay-Dieppe Baie-de-Shediac-Dieppe Vacant 41 13-Kent South 15-Shediac-Beaubassin- Kent-Sud Cap-Pelé Fredericton 45 -Carleton Benoît Bourque (L) Jacques LeBlanc (L) Stewart Fairgrieve (PC) 40 42 -Fredericton-York 18 Hanwell Rick DeSaulniers 21 19 (PANB/AGNB) 43 Moncton 22 Dieppe New Maryland 38-Fredericton- 25-Gagetown-Petitcodiac 17 Ross Wetmore (PC) Fredericton Grand Lake 20 23 ³² 41 ³² Oromocto Kris Austin ³² ³² 40 (PANB/AGNB) 40-Fredericton South 43 Fredricton-Sud ³² David Coon ( PVNBGP ) 24-Albert 44 -Carleton-York Mike Holland (PC) 41-Fredericton North Carl Urquhart (PC) Fredericton-Nord Stephen Horsman ( L ) 37-Oromocto- 16-Memramcook-Tantramar 43-Fredericton West-Hanwell Lincoln- 26-Sussex-Fundy- Megan Mitton (PVNBGP) St. -

What Is Acadians' Electoral Weight in N.B.?

5 octobre 2018 – Telegraph Journal What is Acadians’ electoral weight in N.B.? GABRIEL ARSENEAULT & ROGER OUELLETTE COMMENTARY Acadian Day festivities take place along Water Street in Miramichi. Scholars Gabriel Arseneault and Roger Ouellette write: ‘Since Acadians do not have enough clout in enough ridings to be indispensable to political parties, they must avoid being taken for granted or ignored by political parties.’ PHOTO: JEREMY TREVORS/MIRAMICHI LEADER Francophones now represent about one-third of New Brunswick’s population. How does this demographic weight translate into electoral clout? In which ridings do Acadians have the most influence? And for whom do Acadians vote? This demographic importance is fairly accurately reflected in the electoral boundaries, as shown by the most recent data from the Electoral Boundaries and Representation Commission of New Brunswick. Of the 49 ridings represented in the Legislative Assembly, 16, or 32.7 per cent of the total, have a majority of registered voters whose only mother tongue is French. Francophones also account for more than 20 per cent of the electorate in seven other ridings. In other words, the Acadian vote appears unavoidable in just under half of the ridings, or 23 out of 49. On the other hand, a clear majority of the ridings, 26 out of 49, contain less than 15 per cent francophones. In principle, it would therefore be possible for a party 5 octobre 2018 – Telegraph Journal to obtain a majority of seats without being overly concerned about the French- speaking vote. Over the past 100 years, Acadians have mainly supported the Liberal party. -

Legislative Activities 2019 | 1 As Speaker Until His Appointment in October 2007 As Minister of State for Seniors and Housing

2019 Legislative Activities Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick Legislative Activities 2019 New Brunswick Prepared for The Honourable Daniel Guitard Speaker of the Legislative Assembly New Brunswick October 2, 2020 The Honourable Daniel Guitard Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Room 31, Legislative Building Fredericton, New Brunswick E3B 5H1 Dear Mr. Speaker: I have the honour of submitting this, the thirty-first annual report of Legislative Activities, for the year ended December 31, 2019. Respectfully submitted, Donald J. Forestell Clerk of the Legislative Assembly TABLE OF CONTENTS YEAR IN REVIEW ............................................................................................................... 1 NOTABLE EVENTS ............................................................................................................ 3 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Role of Speaker ............................................................................................................ 5 Role of Members .......................................................................................................... 5 House Activity ............................................................................................................... 6 House Statistics ............................................................................................................ 9 Members of the Legislative Assembly, as of December 31, 2019 ............................. 10 Committee Activity ..................................................................................................... -

What Will Tory Cabinet Look Like?

5 novembre 2018 – Telegraph Journal What will Tory cabinet look like? ADAM HURAS LEGISLATURE BUREAU Andrea Anderson-Mason FREDERICTON • Who will be welcomed into Blaine Higgs’ inner circle? The premier- designate says he’s interviewed all of his Progressive Conservative caucus colleagues for potential cabinet roles. And now, five weeks after New Brunswickers voted in the Sept. 24 election, Higgs doesn’t want to waste any more time. He’s hoping his cabinet can be sworn into hand-picked positions as early as Thursday. “As far as us being ready, I have met with all of my colleagues in preparation for how a cabinet might be put together,” Higgs said.“We’ve done that. That’s one thing out of the way.” With 21 Progressive Conservative colleagues to choose from, we asked five political scientists who Higgs might pick. Sure bets Shippagan-Lamèque-Miscou MLA Robert Gauvin “I think that it might make sense for Higgs to make Robert Gauvin deputy premier and give him a high-profile department and a title, including something like minister responsible for francophone rights,” Jamie Gillies, political scientist at St. Thomas University, said. 5 novembre 2018 – Telegraph Journal “That might help Higgs and the PCs overcome a significant demographic problem with their caucus.” Gauvin checks so many boxes synonymous with cabinet considerations it’s nearly impossible to see how he wouldn’t be handed a big role. He’s the only Progressive Conservative francophone MLA and represents the only seat the party has in the north. Contrast that with Higgs, a unilingual anglophone for a riding in the province’s south, and Gauvin’s involvement becomes integral. -

Electoral Districts of New Brunswick Circonscriptions Électorales Du Nouveau-Brunswick

ELECTORAL DISTRICTS OF NEW BRUNSWICK CIRCONSCRIPTIONS ÉLECTORALES DU NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK 2 -Campbellton-Dalhousie Guy Arseneault (L) Dalhousie 3-Restigouche-Chaleur Campbellton Eel River Daniel Guitard (L) Atholville Crossing 8Æ134 Tide Head 6 -Caraquet Charlo 4-Bathurst West-Beresford Isabelle Thériault (L) 7 -Shippagan-Lamèque-Miscou Balmoral Eric Mallet (L) Æ11 Bathurst-Ouest-Beresford % Æ113 René Legacy (L) 8 Bas-Caraquet Sainte-Marie- Saint-Raphaël Maisonnette Lamèque Belledune Grande- Æ17 Anse % Pointe-Verte 8Æ145 Petit-Rocher Caraquet Nigadoo Saint- Bertrand %Æ11 1 -Restigouche West Léolin Kedgwick Beresford Shippagan Moncton-Riverview-Dieppe Restigouche-Ouest 49-Madawaska Les Lacs-Edmundston %Æ11 Paquetville Gilles LePage (L) Le Goulet Madawaska-Les-Lacs-Edmundston Bathurst Francine Landry (L) Æ135 8 Tracadie 8Æ180 Saint-Isidore %Æ11 Saint-Quentin 18 Æ8 % Æ160 8Æ180 8 8-Tracadie- ³² 5 -Bathurst East-Nepisiguit- 21 Sheila Saint-Isidore Keith Chiasson (L) 8Æ134 Lac Edmundston Bathurst-Est-Nepisiguit- 19 Baker Moncton Rivière-Verte Saint-Isidore 14 Haut-Madawaska Æ120 %Æ17 Denis Landry (L) 8 Sainte-Anne- Æ8 8Æ144 % de-Madawaska Neguac 47-Victoria-La Vallée 17 Dieppe Saint- 22 20 Léonard 9-Miramichi Bay-Neguac Victoria-La-Vallée %Æ11 10-Miramichi Chuck Chiasson (L) Baie-de-Miramichi-Neguac Michelle Conroy Saint- Lisa Harris (L) (PANB/AGNB) André 48-Edmundston-Madawaska Centre 8Æ144 Edmundston-Madawaska-Centre Riverview Jean-Claude D'Amours (L) Drummond 8Æ117 23 Miramichi Æ105 Grand Falls- 8 Grand-Sault Æ108 Memramcook 8 24 Plaster Rock -

Core 1..136 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 7.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 138 Ï NUMBER 134 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Monday, October 6, 2003 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 8179 HOUSE OF COMMONS Monday, October 6, 2003 The House met at 11 a.m. emergency services, which we all know adds an element of danger to their lives as well, are unsung heroes in their communities. Prayers It is time for us to recognize them. It is time for us to stop, look and see what they are doing. Volunteerism is a very important factor in Canada. This afternoon, in an S.O. 31, I also will speak about volunteers in Canada. Canada is considered the number one country PRIVATE MEMBERS' BUSINESS in the world because of volunteers. Volunteers span the whole country from east to west; every community has its volunteers. It is Ï (1105) very important that we as public policy makers recognize that those [English] who volunteer their time for the betterment of others should receive recognition and our thanks. We recognize their contributions and this INCOME TAX ACT is a very small way of recognizing their contributions. The House resumed from May 27 consideration of the motion that Bill C-325, an act to amend the Income Tax Act (deduction for All we are asking is that the workers be allowed to deduct $3,000 volunteer emergency service), be read the second time and referred from their taxable incomes from any source. -

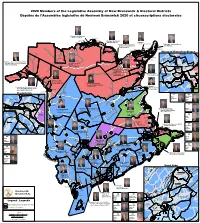

2020 Members of the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick

2020 Members of the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick & Electoral Districts Députés de l'Assemblée législative du Nouveau Brunswick 2020 et circonscriptions électorales 2-Campbellton-Dalhousie Guy Arsenault (L) Dalhousie Campbellton Eel River 3-Restigouche-Chaleur Atholville Crossing Tide Head Daniel Guitard (L) 6-Caraquet Charlo 4-Bathurst West-Beresford Isabelle Thériault (L) 7-Shippagan-Lamèque-Miscou Balmoral %Æ11 Bathurst-Ouest-Beresford Eric Mallet (L) René Legacy (L) Bas-Caraquet Sainte-Marie- Saint-Raphaël Maisonnette Lamèque Belledune Grande- Æ17 Anse % Pointe-Verte Moncton-Riverview-Dieppe 18-Moncton East Petit-Rocher Caraquet Moncton-Est Nigadoo Saint- Bertrand %Æ11 Léolin Kedgwick Beresford Shippagan 21-Moncton Northwest %Æ11 Paquetville Le Goulet Moncton-Nord-Ouest 49-Madawaska Les Lacs-Edmundston Bathurst Tracadie Madawaska-Les-Lacs-Edmundston 1-Restigouche West Saint-Isidore Francine Landry (L) Restigouche-Ouest %Æ11 Saint-Quentin Gilles Lepage (L) %Æ8 Moncton 19-Moncton Centre ³² 5-Bathurst East-Nepisiguit- Moncton-Centre Saint-Isidore Bathurst-Est-Nepisiguit- Lac Edmundston 8-Tracadie-Sheila 22-Moncton Southwest Baker Saint-Isidore Moncton-Sud-Ouest 20-Moncton South Keith Chiasson (L) Rivière-Verte Denis Landry (L) Moncton-Sud Dieppe Haut-Madawaska %Æ17 Sainte-Anne- %Æ8 de-Madawaska Neguac 47-Victoria-La Vallée 17-Dieppe Saint- Riverview Léonard Victoria-La-Vallée %Æ11 Chuck Chiasson (L) 9-Miramichi Bay-Neguac 23-Riverview Saint- Baie-de-Miramichi-Neguac André Lisa Harris (L) 10-Miramichi 48-Edmundston-Madawaska Centre -

WINTER 2020 Shutterstock/720527635/Tammy Kelly

Canadian eview “opîkiskwêstamâkêw, ninîpawin anohc kihci-kîkway ôma kâ-nohtê-mâmiskohtamân ôtê ohci kâ-ôhciyân…” "Madam Speaker, I rise today to speak about an issue of great importance to my constituents and my community..." V olume 43, No. 4 Confederate Association, and when the Dominion of Newfoundland chose to join Canada in the 1948 referenda, he became leader of the Liberal Party. In 1949, he was elected Premier of the newest province in Canada, a job he held for 23 years. W.R. Smallwood was born in 1928 in Corner Brook on the west coast of the island, while his father ran a newspaper in the city. He was the middle of three children, graduating from Curtis Academy in St. John’s and going on to Memorial University and then to Dalhousie University for Law. W.R. Smallwood practiced law in St. John’s, until his successful election to the House of Assembly for the District of Green Bay in 1956. The Father of Confederation and William R. Smallwood Joseph R. Smallwood his son sat on the same side of Photos from the Legislative Library Subject Files Collection the House together for 15 years. While W.R. Smallwood was never a part of his father’s Cabinet, there In a place known for asking “who’s your father?” in order were some interesting exchanges during their time in to determine where you fit in the fabric of the province, it’s the Chamber – one such instance occurred in May of no wonder that our House of Assembly has seen so many 1971. -

What Will the Tory Cabinet Look Like?

5 novembre 2018 – Times & Transcript What will the Tory cabinet look like? ADAM HURAS LEGISLATURE BUREAU Progressive Conservative Leader Blaine Higgs, backed by his caucus, talks to the media after the Liberal government fell on Friday. PHOTO: TOM BATEMAN / TIMES & TRANSCIPT FREDERICTON • Who will be welcomed into Blaine Higgs’ inner circle? The premier-designate says he’s interviewed all of his Progressive Conservative caucus colleagues for potential cabinet roles. And now, five weeks after New Brunswickers voted in the Sept. 24 election, Higgs doesn’t want to waste any more time. He’s hoping his cabinet can be sworn into hand-picked positions as early as Thursday. “As far as us being ready, I have met with all of my colleagues in preparation for how a cabinet might be put together,” Higgs said.“We’ve done that. That’s one thing out of the way.” With 21 Progressive Conservative colleagues to choose from, we asked five political scientists who Higgs might pick. 5 novembre 2018 – Times & Transcript SURE BETS Shippagan-Lamèque-Miscou MLA Robert Gauvin “I think that it might make sense for Higgs to make Robert Gauvin deputy premier and give him a high-profile department and a title, including something like minister responsible for francophone rights,” Jamie Gillies, political scientist at St. Thomas University, said. “That might help Higgs and the PCs overcome a significant demographic problem with their caucus.” Gauvin checks so many boxes synonymous with cabinet considerations it’s nearly impossible to see how he wouldn’t be handed a big role. He’s the only Progressive Conservative francophone MLA and represents the only seat the party has in the north.