Professional Sports and Public Behavior Transcript of Plenary Session Held in Washington, DC, on December 8, 1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos + Cards Base Autos Memorabilia Memorabilia Luka Doncic 1112 0 145 630 337 Joe Dumars 1101 0 460 441 200 Grant Hill 1030 0 560 220 250 Nikola Jokic 998 154 420 236 188 Elie Okobo 982 0 140 630 212 Karl-Anthony Towns 980 154 0 752 74 Marvin Bagley III 977 0 10 630 337 Kevin Knox 977 0 10 630 337 Deandre Ayton 977 0 10 630 337 Trae Young 977 0 10 630 337 Collin Sexton 967 0 0 630 337 Anthony Davis 892 154 112 626 0 Damian Lillard 885 154 186 471 74 Dominique Wilkins 856 0 230 550 76 Jaren Jackson Jr. 847 0 5 630 212 Toni Kukoc 847 0 420 235 192 Kyrie Irving 846 154 146 472 74 Jalen Brunson 842 0 0 630 212 Landry Shamet 842 0 0 630 212 Shai Gilgeous- 842 0 0 630 212 Alexander Mikal Bridges 842 0 0 630 212 Wendell Carter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Hamidou Diallo 842 0 0 630 212 Kevin Huerter 842 0 0 630 212 Omari Spellman 842 0 0 630 212 Donte DiVincenzo 842 0 0 630 212 Lonnie Walker IV 842 0 0 630 212 Josh Okogie 842 0 0 630 212 Mo Bamba 842 0 0 630 212 Chandler Hutchison 842 0 0 630 212 Jerome Robinson 842 0 0 630 212 Michael Porter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Troy Brown Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Joel Embiid 826 154 0 596 76 Grayson Allen 826 0 0 614 212 LaMarcus Aldridge 825 154 0 471 200 LeBron James 816 154 0 662 0 Andrew Wiggins 795 154 140 376 125 Giannis 789 154 90 472 73 Antetokounmpo Kevin Durant 784 154 122 478 30 Ben Simmons 781 154 0 627 0 Jason Kidd 776 0 370 330 76 Robert Parish 767 0 140 552 75 Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos -

Downloaded Off Washington on Wednesday

THE TU TS DAILY miereYou Read It First Friday, January 29,1999 Volume XXXVIII, Number 4 1 Dr. King service brings the Endowment fund created in honor of Joseph Gonzalez . Year of Non-violence to end A bly BROOKE MENSCHEL of the First Unitaridn by DANIEL BARBARlSI be marked with a special plaque Daily Editorial Board Universalist Parish in Daily Editorial Board on the inside cover, in memory of The University-wide Year of Cambridge. He is also The memory and legacy of Gonzalez. an active member of Non-vio1ence;which began last Tufts student Joseph Gonzalez, Michael Juliano, one of the National Asso- Martin Luther King Day, ended who passed away suddenly last Gonzalez’ closest friends, de- ciation for the Ad- this Wednesday night with “A year, will be commemorated at scribed the fund as a palpable, vancement of Col- Pilgrimage to Nonviolence,” a Tufts through the creation of an concrete method of preserving ored Persons commemorative service for King. endowment in his honor. The en- Gonzalez’memory. The service, which was held in (NAACP), a visiting dowment, given to the Tisch Li- “Therearea lotofthingsabout lecturer at Harvard’s Goddard Chapel, used King’s own brary for the purpose ofpurchas- Joey you can remember, butthis Divinity school, and words as well as the words of ing additional literature, was ini- book fund is a tangible legacy ... the co-founder and many others to commemorate both tiated through a $10,000 dona- thisone youcan actuallypickup co-director of the theyear and the man. The campus tion by Gonzalez’ parents, Jo- and take in your hand,” Juliano Tuckman Coalition, a chaplains Rev. -

2017-18 COLORADO BASKETBALL Colorado Buffaloes

colorado buffaloes All-America Selections Jack Harvey Robert Doll 1939 & 1940 1942 In his back-to-back All- Bob Doll was the big-play man for America campaigns, Jack coach Frosty Cox’s 1941-42 Big Seven Harvey led the Buffs to two Championship squad. Doll, along with conference championships fellow All-American Leason McCloud and a trip to the NCAA helped lead CU to a 16-2 record and Tournament in his senior the NCAA Western Tournament finals season. During those as a senior. He scored 168 points (9.4 two years, CU posted an ppg.) and was known as an outstanding amazing 31-8 mark and rebounder and controlled the paint in received recognition as many CU wins. He was also renowned the No. 1 team in the for his shooting prowess, finishing second land. Known for his tough to McCloud in scoring. An unanimous All- defense, Harvey proved to Big Seven selection, Doll was selected to be key in numerous Buff All-America teams by Look, Pic and Time victories. He was also an magazines. He was also tabbed as MVP of outstanding ball-handler for New York’s Metropolitan Tournament as a a big man and was a key sophomore and was a huge factor in CU’s component in the CU fast three conference titles in a four-year span. break. A solid All-Conference After graduation, Doll went on to play for performer, Harvey is the the Boston Celtics. only CU cager to be selected twice as an All-American Leason McCloud 1942 Jim Willcoxon The leading scorer for the 1939 1942 Big Seven Champion Buffs, Known for his defense, Leason McCloud was Coach Frosty Jim Willcoxon continued Cox’s “go-to guy.” Known for his Coach Frosty Cox’s tradition silky-smooth shot, McCloud was of talented cagers. -

Middle of the Pack Biggest Busts Too Soon to Tell Best

ZSW [C M Y K]CC4 Tuesday, Jun. 23, 2015 ZSW [C M Y K] 4 Tuesday, Jun. 23, 2015 C4 • SPORTS • STAR TRIBUNE • TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2015 TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2015 • STAR TRIBUNE • SPORTS • C5 2015 NBA DRAFT HISTORY BEST OF THE REST OF FIRSTS The NBA has held 30 drafts since the lottery began in 1985. With the Wolves slated to pick first for the first time Thursday, staff writer Kent Yo ungblood looks at how well the past 30 N o. 1s fared. Yo u might be surprised how rarely the first player taken turned out to be the best player. MIDDLE OF THE PACK BEST OF ALL 1985 • KNICKS 1987 • SPURS 1992 • MAGIC 1993 • MAGIC 1986 • CAVALIERS 1988 • CLIPPERS 2003 • CAVALIERS Patrick Ewing David Robinson Shaquille O’Neal Chris Webber Brad Daugherty Danny Manning LeBron James Center • Georgetown Center • Navy Center • Louisiana State Forward • Michigan Center • North Carolina Forward • Kansas Forward • St. Vincent-St. Mary Career: Averaged 21.0 points and 9.8 Career: Spurs had to wait two years Career: Sixth all-time in scoring, O’Neal Career: ROY and a five-time All-Star, High School, Akron, Ohio Career: Averaged 19 points and 9 .5 Career: Averaged 14.0 pts and 5.2 rebounds over a 17-year Hall of Fame for Robinson, who came back from woN four titles, was ROY, a 15-time Webber averaged 20.7 points and 9.8 rebounds in eight seasons. A five- rebounds in a career hampered by Career: Rookie of the Year, an All- career. R OY. -

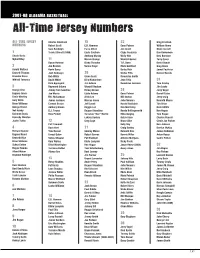

All-Time Jersey Numbers

2007-08 ALABAMA BASKETBALL All-Time Jersey Numbers ALL-TIME JERSEY Charles Cleveland 15 23 Greg Freeman NUMBERS Robert Scott E.B. Hammer Gene Palmer William Henry Sam Randolph Farra Alford Jim Grant Glenn Garrett 1 Travis Stinnett (1999) Eddie Cauthen Clyde Frederick Don Bowerman Chuck Davis Anthony Murray Wally Holt Desi Barmore Mykal Riley 11 Marvin Orange Wendell Garner Terry Coner Dyson Hamner Blake Thrasher T.R. Dunn David Benoit 2 Jim Bratton Verice Cloyd Mark Gottfried Greg Glass Gerald Wallace Kevin Barry Darby Rich Jamal Faulkner Emmett Thomas Jack Kubiszyn 20 Walter Pitts Damon Bacote Brandon Davis Bob White Glenn Scott Demetrius Smith Mikhail Torrance David White Billy Richardson Jean Felix 31 Dick Appleyard Jim Adkins Demetrius Jemison Tom Crosby 3 Raymond Odums Wendell Hudson Jim Lewis George Linn Jimmy Tom Goostree Rickey Brown 24 Jerry Vogel Eugene Jones Joe Morris Eddie Adams Gene Palmer Darrell Estes Ennis Whatley Eric Richardson Alvin Lee Bill Sexton Jerry Craig Gary White James Jackson Marcus Jones John Norman Kenneth Moses Brian Williams Earnest Brown Jeff Lovell Harold Goldstein Tim Orton George Brown Anthony Brown Reggie Lee Ron McKinney David White Neil Ashby D.J. Towns Dejuan Shambley Randy Hollingsworth Ken Hogue Solomon Davis Rico Pickett Terrance “Doc” Martin Mike Quigley Tom Hogue Kennedy Winston LaKory Daniels Butch Dean Charles Russell Justin Tubbs 12 Greg Cage Bruce Albe Clevie Joe Parker Pat Trammell Kelly Shy Ken Johnson 4 Dave Hart 21 Craig Dudley Derrick McKey Richard Gunder Tom Hoover Sammy Moore Kenneth -

Professional Sports Leagues and the First Amendment: a Closed Marketplace Christopher J

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 13 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring Professional Sports Leagues and the First Amendment: A Closed Marketplace Christopher J. McKinny Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Christopher J. McKinny, Professional Sports Leagues and the First Amendment: A Closed Marketplace, 13 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 223 (2003) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol13/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS PROFESSIONAL SPORTS LEAGUES AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT: A CLOSED MARKETPLACE 1. INTRODUCTION: THE CONTROVERSY Get murdered in a second in the first degree Come to me with faggot tendencies You'll be sleeping where the maggots be... Die reaching for heat, leave you leaking in the street Niggers screaming he was a good boy ever since he was born But fluck it he gone Life must go on Niggers don't live that long' Allen Iverson, 2 a.k.a. "Jewelz," 3 from the song "40 Bars." These abrasive lyrics, quoted from Allen Iverson's rap composition "40 Bars," sent a shock-wave of controversy throughout the National Basketball 1. Dave McKenna, Cheap Seats: Bum Rap, WASH. CITY PAPER, July 6-12, 2001, http://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/archives/cheap/2001/cheap0706.html (last visited Jan. 15, 2003). 2. Allen Iverson, a 6-foot, 165-pound shooting guard, currently of the Philadelphia 76ers, was born June 7, 1975 in Hampton, Virginia. -

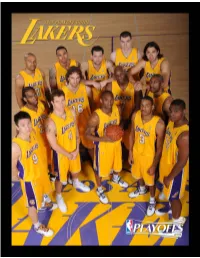

2008-09 Playoff Guide.Pdf

▪ TABLE OF CONTENTS ▪ Media Information 1 Staff Directory 2 2008-09 Roster 3 Mitch Kupchak, General Manager 4 Phil Jackson, Head Coach 5 Playoff Bracket 6 Final NBA Statistics 7-16 Season Series vs. Opponent 17-18 Lakers Overall Season Stats 19 Lakers game-By-Game Scores 20-22 Lakers Individual Highs 23-24 Lakers Breakdown 25 Pre All-Star Game Stats 26 Post All-Star Game Stats 27 Final Home Stats 28 Final Road Stats 29 October / November 30 December 31 January 32 February 33 March 34 April 35 Lakers Season High-Low / Injury Report 36-39 Day-By-Day 40-49 Player Biographies and Stats 51 Trevor Ariza 52-53 Shannon Brown 54-55 Kobe Bryant 56-57 Andrew Bynum 58-59 Jordan Farmar 60-61 Derek Fisher 62-63 Pau Gasol 64-65 DJ Mbenga 66-67 Adam Morrison 68-69 Lamar Odom 70-71 Josh Powell 72-73 Sun Yue 74-75 Sasha Vujacic 76-77 Luke Walton 78-79 Individual Player Game-By-Game 81-95 Playoff Opponents 97 Dallas Mavericks 98-103 Denver Nuggets 104-109 Houston Rockets 110-115 New Orleans Hornets 116-121 Portland Trail Blazers 122-127 San Antonio Spurs 128-133 Utah Jazz 134-139 Playoff Statistics 141 Lakers Year-By-Year Playoff Results 142 Lakes All-Time Individual / Team Playoff Stats 143-149 Lakers All-Time Playoff Scores 150-157 MEDIA INFORMATION ▪ ▪ PUBLIC RELATIONS CONTACTS PHONE LINES John Black A limited number of telephones will be available to the media throughout Vice President, Public Relations the playoffs, although we cannot guarantee a telephone for anyone. -

Notre Dame Scholastic, Vol. 87, No. 01

Hickey-Freeman Society Brand Dobbi DEDICATED TO THE PRINCIPLES OF SUPERLATIVE QUALITY and COURTEOUS. CONSCIENTIOUS SERVICE Here—You are always a Guest before you are a Custonner GILBERT'S 813-817 S. Michigan St. Index of Advertisers UNIVERSITY CALENDAR Spring Semester of 1946 Adler, Max 4-5-42 Arrow Shirts 42 This calendar for the spring semester has been revised, due to Blocks 41 circumstances arising from the return to a normal academic program. Book Shop 38" The calendar printed below is the correct one. Bookstore ... 34 Bruggners ... 37 Burke ... 37 April 18—^Thursday: Business Systems ... 33 Easter recess begins at 4:00 p.m. Cain ... 41 Campus Centenary Set ... 33 April 22—Monday: ... 44 Chesterfield Classes resume at 8:00 a,m. Coca-Cola _ 35 Copp's Music Shop ... 37 May I—^Wednesday: Dining Hall Store ... 36 Douglas Shoe ... 40 Latest date for midsemester report of deficient students. Du Pont ... 9 Georges ... 39 May 13 to 18—Monday to Saturday: General Electric . ... 7 Preregistration for courses in the Fall Semester which will - 2 Gilbert, Paul open September 10. Grundy, Dr. O. J. ... 41 Hans-Rintzsch ... 36 June 24 to 28—Monday to Friday: Longines ... 8 Lowers _. 33 Semester examinations for all students. Lucas, Dr. Robert ... 41 Marvin's ... 38 June 29—Saturday: Mitchell (Insurance) ... 38 Class-day exercises. Oliver Hotel .. 32 ... 32 Parker-Winter'rowd . June 30—Sunday: ... 41 Probst, Dr. Commencement Mass and baccalaureate sermon. Conferring Rose Dental Group .. 41 Singler, Dr ... 41 of degrees at 4:00 p.m. ... 39 Sonneborns Note: The scholastic year of 1946-47 will open with South Bend X-Ray 41 Sunny Italy 36 registration on September 10,11 and 12. -

Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports

Fordham Law Review Volume 67 Issue 4 Article 9 1999 Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports Jason M. Pollack Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jason M. Pollack, Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports, 67 Fordham L. Rev. 1645 (1999). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol67/iss4/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports Cover Page Footnote I dedicate this Note to Mom and Momma, for their love, support, and Chicken Marsala. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol67/iss4/9 TAKE MY ARBITRATOR, PLEASE: COMMISSIONER "BEST INTERESTS" DISCIPLINARY AUTHORITY IN PROFESSIONAL SPORTS Jason M. Pollack* "[I]f participants and spectators alike cannot assume integrity and fairness, and proceed from there, the contest cannot in its essence exist." A. Bartlett Giamatti - 19871 INTRODUCTION During the first World War, the United States government closed the nation's horsetracks, prompting gamblers to turn their -

Award Winners

AWARD WINNERS FIRST TEAM CONSENSUS ALL-AMERICANS AWARD 1908-09 Ray Scanlon 1924-25 Nobel Kizer WINNERS 1926-27 John Nyikos 1931-32 Edward “Moose” Krause 1932-33 Edward “Moose” Krause 1933-34 Edward “Moose” Krause BYRON V. KANALEY AWARD 1935-36 John Moir Perhaps the most prestigious honor awarded to Notre Dame student- 1935-36 Paul Nowak athletes is the Byron V. Kanaley Award. Presented each year since 1927 at 1936-37 John Moir commencement exercises, the Kanaley Awards go to the senior monogram 1936-37 Paul Nowak athletes who have been most exemplary as students and leaders. The 1937-38 John Moir awards, selected by the Faculty Board on Athletics, are named in honor of a 1937-38 Paul Nowak 1904 Notre Dame graduate who was a member of the baseball team as an 1943-44 Leo Klier undergraduate. Kanaley went on to a successful banking career in Chicago 1944-45 Bill Hassett and served the University in the Alumni Association and as a lay trustee 1945-46 Leo Klier from 1915 until his death in 1960. 1947-48 Kevin O’Shea 1970-71 Austin Carr 1929 Francis Crowe 1973-74 John Shumate 1932 Thomas Burns 1974-75 Adrian Dantley 1938 Ray Meyer 1975-76 Adrian Dantley 1954 Dick Rosenthal 1999-2000 Troy Murphy 1957 Jon Smyth 2000-01 Troy Murphy 1958 John McCarthy 2014-15 Jerian Grant 1969 Bob Arnzen 1974 Gary Novak 1990 Scott Paddock SECOND TEAM CONSENSUS ALL-AMERICANS 1997 Pete Miller 1942-43 Bob Rensberger 1998 Pat Garrity 1945-46 William Hassett 2012 Tim Abromaitis 1949-50 Kevin O’Shea 1958-59 Tom Hawkins FRANCIS PATRICK O’CONNOR AWARD 1969-70 Austin Carr The University of Notre Dame began presenting the Francis Patrick O’Connor 1978-79 Kelly Tripucka Awards in 1993, named in honor of a former Notre Dame wrestler who died 1980-81 Kelly Tripucka in 1973 following his freshman year at the University. -

64812 CU Mens Bball Book.Indd

colorado buffaloes All-America Selections Jack Harvey 1939 & 1940 In his back-to-back All-America campaigns, Robert Doll Jack Harvey led the 1942 Buffs to two conference Bob Doll was the big-play man for championships and a trip coach Frosty Cox’s 1941-42 Big Seven to the NCAA Tournament Championship squad. Doll, along with in his senior season. fellow All-American Leason McCloud During those two years, helped lead CU to a 16-2 record and CU posted an amazing the NCAA Western Tournament fi nals 31-8 mark and received as a senior. He scored 168 points (9.4 recognition as the No. 1 ppg.) and was known as an outstanding team in the land. Known rebounder and controlled the paint in for his tough defense, many CU wins. He was also renowned Harvey proved to be for his shooting prowess, finishing key in numerous Buff second to McCloud in scoring. An victories. He was also an unanimous All-Big Seven selection, outstanding ball-handler Doll was selected to All-America teams for a big man and was a by Look, Pic and Time magazines. He key component in the CU was also tabbed as MVP of New York’s fast break. A solid All- Metropolitan Tournament as a sophomore and was a huge factor in CU’s three Conference performer, conference titles in a four-year span. After graduation, Doll went on to play for the Harvey is the only CU Boston Celtics. cager to be selected twice as an All-American Leason McCloud 1942 Jim Willcoxon The leading scorer for the 1939 1942 Big Seven Champion Buffs, Known for his defense, Leason McCloud was Coach Frosty Jim Willcoxon continued Cox’s “go-to guy.” Known for Coach Frosty Cox’s tradition his silky-smooth shot, McCloud of talented cagers. -

April-2011-Prices-Realized.Pdf

April 2011 Auction Prices Realized Lot # Name 1 RED AUERBACH'S GROUP OF (4) 1940'S WASHINGTON CAPITOLS GAME ACTION PHOTOS $385.20 2 RED AUERBACH'S CA. 1947 WASHINGTON CAPITOLS ORIGINAL NEWSPAPER ART BY COAKLEY INSCRIBED TO RED AUERBACH $866.40 3 RED AUERBACH'S PAIR OF 1949 WASHINGTON CAPITOLS PHOTOGRAPHS - ONE AUTOGRAPHED $241.20 RED AUERBACH'S INLAID MAHOGANY PIPE STAND WITH SIX PIPES WITH ENGRAVED PLAQUE "DOT TO ARNOLD JUNE 5, 1942" - A GIFT FROM RED'S 4 WIFE ON THE OCCASION OF THEIR FIRST WEDDING ANNIVERSARY $2,772.00 5 RED AUERBACH'S PHOTO INSCRIBED TO HIM BY CLARK GRIFFITH $686.40 6 RED AUERBACH'S PERSONAL COLLECTION OF (5) EARLY BASKETBALL HANDBOOKS AND GUIDES $514.80 RED AUERBACH'S FIRST CONTRACT TO COACH THE BOSTON CELTICS EXECUTED AND SIGNED IN 1950 BY AUERBACH AND WALTER BROWN WITH 7 RELATED PHOTO $14,678.40 8 RED AUERBACH'S PERSONAL 1950-51 BOSTON CELTICS PHOTO ALBUM $1,138.80 9 1950 BOB COUSY BOSTON CELTICS GAME WORN ROOKIE JERSEY FROM RED AUERBACH'S PERSONAL COLLECTION $41,434.80 10 RED AUERBACH'S PRESENTATIONAL CIGAR HUMIDOR FROM THE 1954-55 BOSTON CELTICS WITH ENGRAVED TEAM SIGNATURES ON SILVER PLACARD $18,840.00 11 RED AUERBACH'S EARLY 1950'S FRAMED HAND COLORED PHOTOGRAPH $2,000.40 TWO PAIRS OF 1950'S BOSTON CELTICS GAME WORN SHORTS ATTRIBUTED TO DERMIE O'CONNELL AND BOB DONHAM FROM RED AUERBACH'S 12 COLLECTION $924.00 13 RED AUERBACH'S CA. 1950'S ORIGINAL NEWSPAPER ARTWORK BY BOB COYNE $1,108.80 14 RED AUERBACH'S 1954 ORIGINAL NEWSPAPER ARTWORK BY PHIL BISSELL $1,008.00 15 RED AUERBACH'S 1955 ORIGINAL NEWSPAPER ARTWORK BY PHIL BISSELL $316.80 16 RED AUERBACH'S PERSONAL 1955-56 BOSTON CELTICS VINTAGE TEAM SIGNED PHOTO $704.40 17 RED AUERBACH'S 1956 ORIGINAL NEWSPAPER ARTWORK BY PHIL BISSELL $1,108.80 18 RED AUERBACH'S VINTAGE SIGNED PERSONAL 1957 NBA OFFICIAL BASKETBALL HANDBOOK $1,969.20 19 RED AUERBACH'S LATE 1950'S ORIGINAL NEWSPAPER ARTWORK BY PHIL BISSELL $566.40 20 RED AUERBACH'S OWN BILL RUSSELL VINTAGE ROOKIE-ERA SIGNED PHOTOGRAPH $6,543.60 21 RED AUERBACH'S CA.