A Revision of the Genus Kunzea (Myrtaceae) I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildflowers to Grow in Your Garden Here Is the Key to the List Large

Wildflowers to grow in your garden Here is the key to the list Trees Ground covers Shrubs Eucalypts Banksias Myrtle family Banksias Others Baeckea Other Beaufortia Calothamnus Chamelaucium Hypocalymna Kunzea Melaleuca and Callistemon Scholtzia Thryptomene Verticordia Large trees. Think very carefully before you plant them! Large trees, such as lemon scented gums or spotted gums may look great in parks - at least local councils seem to think so (we would rather see local plants). But you may regret planting them in a modern small garden. That doesn't mean there is no room for trees. There are hundreds of attractive small trees that grow very well in native gardens. Here are just a few. Small trees Eucalypts with showy flowers. Eucalytpus caesia Comes in two sub species with the one known as "silver princess" being readily available in Perth. Lovely multi- stemmed weeping tree with pendulous pink flowers and silver-bell fruits. E. torquata Small upright tree with attractive pink flowers. Very drought resistant. E. ficifolia Often called the WA Flowering gum. Ranges in size from small to quite large and in flower colour from deep red to = Corymbia ficifolia orange to pale pink. In WA subject to a serious disease - called canker. Many trees succumb when about 10 or so years old, either dying or becoming very unhealthy. E. preissiana Bell fruited mallee. Small tree (or shrub) with bright yellow flowers. E. erythrocorys Illyarrie, red cap gum or helmet nut gum. Large golden flowers in February preceded by a bright red bud cap. Tree tends to be bit floppy and to need pruning. -

Salinity Tolerance of Muntries (Kunzea Pomifera F. Muell.)

HORTSCIENCE 53(11):1562–1569. 2018. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI13280-18 When crops are subjected to soil salinity levels exceeding their tolerance levels, plant Kunzea growth declines and crop yields decrease. For Salinity Tolerance of Muntries ( example, strawberry (sensitive) exhibits a re- pomifera duced number of leaves and leaf area at F. Muell.), a Native Food Crop 30 mM NaCl and a 20% reduction in fruit yield (Garriga et al., 2015). A significant in Australia decrease in growth of date palm (tolerant) –1 is observed at 7.3 dS·m , and fruit yield is Chi M. Do, Kate L. Delaporte, Vinay Pagay, and Carolyn J. Schultz1 reduced by 25% (Department of Agricul- School of Agriculture, Food and Wine, Waite Research Institute, The ture and Food, 2016). Olive is an example of University of Adelaide, PMB1, Glen Osmond, SA, 5064, Australia a moderately tolerant fruit crop that shows relatively minor impacts at high salinity (7.5 Additional index words. alternative fruits, homeostasis, potassium, salinity stress, sodium dS·m–1), with 20% to 30% reduction in oil chloride, sustainable agriculture and fresh-fruit yield compared with nonsalt- stressed plants (Al-Rawi and Al-Mohemdy, Abstract . Identifying productive food crops that tolerate moderate soil salinity is critical 2001). In citrus (lime and lemon, both sensi- Kunzea pomifera for global food security. We evaluate the salinity tolerance of tive crops), moderate salinity (50 mM NaCl) (muntries), a traditional Indigenous food plant that grows naturally in coastal regions reduces leaf number, area, and thickness of southern Australia and thrives on relatively low rainfall. -

Puccinia Psidii Winter MAY10 Tasmania (C)

MAY10Pathogen of the month – May 2010 a b c Fig. 1. Puccinia psidii; (a) Symptoms on Eucalyptus grandis seedling; (b) Stem distortion and multiple branching caused by repeated infections of E. grandis, (c) Syzygium jambos; (d) Psidium guajava; (e) Urediniospores. Photos: A. Alfenas, Federal University of Viçosa, Brazil (a, b,d and e) and M. Glen, University of Tasmania (c). Common Name: Guava rust, Eucalyptus rust d e Winter Disease: Rust in a wide range of Myrtaceous species Classification: K: Fungi, D: Basidiomycota, C: Pucciniomycetes, O: Pucciniales, F: Pucciniaceae Puccinia psidii (Fig. 1) is native to South America and is not present in Australia. It causes rust on a wide range of plant species in the family Myrtaceae. First described on guava, P. psidii became a significant problem in eucalypt plantations in Brazil and also requires control in guava orchards. A new strain of the rust severely affected the allspice industry in Jamaica in the 1930s. P. psidii has spread to Florida, California and Hawaii. In 2007, P. psidii arrived in Japan, on Metrosideros polymorpha cuttings imported from Hawaii. Host Range: epiphytotics on Syzygium jambos in Hawaii, with P. psidii infects young leaves, shoots and fruits of repeated defoliations able to kill 12m tall trees. many species of Myrtaceae. Key Distinguishing Features: Impact: Few rusts are recorded on Myrtaceae. These include In the wild, in its native range, P. psidii has only a P. cygnorum, a telial rust on Kunzea ericifolia, and minor effect. As eucalypt plantations in Brazil are Physopella xanthostemonis on Xanthostemon spp. in largely clonal, impact in areas with a suitable climate Australia. -

History and Management of Culham Inlet, a Coastal Salt Lake in South-Western Australia

JournalJournal of ofthe the Royal Royal Society Society of Westernof Western Australia, Australia, 80(4), 80:239-247, December 1997 1997 History and management of Culham Inlet, a coastal salt lake in south-western Australia E P Hodgkin 86 Adelma Road, Dalkeith, WA 6009 email: [email protected] Manuscript received August 1996; accepted May 1997. Abstract When Culham Inlet was first flooded by the Holocene rise in sea level it was an estuary, but in historic times it has been a salt lake closed by a high sea bar. It is in an area of low rainfall and episodic river flow and sometimes all water is lost by evaporation to below sea level. With above average rainfall in 1989 and 1992, high water levels in the Inlet flooded farm paddocks and threatened to break the bar and a road along it from Hopetoun to the Fitzgerald River National Park. In 1993 the bar was breached to release flood water, and the Inlet was briefly an estuary. Engineering measures designed to restore road access and prevent flooding are examined for their potential to restore the Inlet to its pre-1993 condition of a productive ecosystem. Recent clearing in the catchments of Culham Inlet and nearby estuaries in the south coast low rainfall area has increased river flow to them and appears to have caused their bars to break more frequently. Introduction (Fig 2) that is only known to have broken naturally once, In historic times Culham Inlet has been a coastal in 1849. The bar was broken artificially in 1920, but for lagoon on a semi-arid part of the south coast of Western over 70 years since then the Inlet has absorbed river flow Australia (Fig 1), separated from the sea by a high bar without the bar breaking, until 1993. -

N E W S L E T T E R

N E W S L E T T E R PLANTS OF TASMANIA Nursery and Gardens 65 Hall St Ridgeway TAS 7054 Open 7 Days a week – 9 am to 5 pm Closed Christmas Day, Boxing Day and Good Friday Phone: (03) 6239 1583 Fax: (03) 6239 1106 Email: [email protected] Newsletter 26 Spring 2011 Website: www.potn.com.au Hello, and welcome to the spring newsletter for 2011! News from the Nursery We are madly propagating at the moment, with many thousands of new cuttings putting their roots out and seedlings popping their heads up above the propagating mix. It is always an exciting time, as we experiment with seed from new species – sometimes they work, and sometimes we understand why we’ve never grown them before... New plants should start being put out into the sales area soon – fresh-faced little things ready to pop into the ground! We have recently purchased a further block of land from the ex-neighbours Jubilee Nursery, now sadly closed, that will give us a lot more flexibility and the ability to grow and store more plants. As mentioned last newsletter we have done some major revamping in the garden. A lot of work by all the staff has led to a much more open garden with a lovely Westringia brevifolia hedge (well, it will be a hedge when it grows a bit), another Micrantheum hexandrum Cream Cascade hedge-to-be, lots of Correas, Lomatias and Baueras. Where we sell a few forms of a particular species we have tried to plant examples of each so that we can show you what they are like. -

Muntries the Domestication and Improvement of Kunzea Pomifera (F.Muell.)

Muntries The domestication and improvement of Kunzea pomifera (F.Muell.) A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation by Tony Page January 2004 RIRDC Publication No 03/127 RIRDC Project No UM-52A © 2004 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 0 0642 58693 4 ISSN 1440-6845 Muntries: The domestication and improvement of Kunzea pomifera (F.Muell) Publication No. 03/127 Project No: UM-52A The views expressed and the conclusions reached in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of persons consulted. RIRDC shall not be responsible in any way whatsoever to any person who relies in whole or in part on the contents of this report. This publication is copyright. However, RIRDC encourages wide dissemination of its research, providing the Corporation is clearly acknowledged. For any other enquiries concerning reproduction, contact the Publications Manager on phone 02 6272 3186. Researcher Contact Details Tony Page 500 Yarra Boulevard RICHMOND VIC 3121 Phone: 03 9250 6800 Fax: 03 92506885 Email: [email protected] In submitting this report, the researcher has agreed to RIRDC publishing this material in its edited form. RIRDC Contact Details Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Level 1, AMA House 42 Macquarie Street BARTON ACT 2600 PO Box 4776 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Phone: 02 6272 4539 Fax: 02 6272 5877 Email: [email protected]. Website: http://www.rirdc.gov.au Published in January 2004 Printed on environmentally friendly paper by Canprint ii Foreword Many Australian native plant foods have the potential to broaden the culinary and nutritional composition of the human diet, both in Australia and worldwide. -

Flora and Vegetation Survey of the Proposed Kwinana to Australind Gas

__________________________________________________________________________________ FLORA AND VEGETATION SURVEY OF THE PROPOSED KWINANA TO AUSTRALIND GAS PIPELINE INFRASTRUCTURE CORRIDOR Prepared for: Bowman Bishaw Gorham and Department of Mineral and Petroleum Resources Prepared by: Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd November 2003 MATTISKE CONSULTING PTY LTD DRD0301/039/03 __________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Location................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 Climate .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.3 Vegetation.............................................................................................................................................. 3 2.4 Declared Rare and Priority Flora......................................................................................................... 3 2.5 Local and Regional Significance........................................................................................................... 5 2.6 Threatened -

Inventory of Taxa for the Fitzgerald River National Park

Flora Survey of the Coastal Catchments and Ranges of the Fitzgerald River National Park 2013 Damien Rathbone Department of Environment and Conservation, South Coast Region, 120 Albany Hwy, Albany, 6330. USE OF THIS REPORT Information used in this report may be copied or reproduced for study, research or educational purposed, subject to inclusion of acknowledgement of the source. DISCLAIMER The author has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information used. However, the author and participating bodies take no responsibiliy for how this informrion is used subsequently by other and accepts no liability for a third parties use or reliance upon this report. CITATION Rathbone, DA. (2013) Flora Survey of the Coastal Catchments and Ranges of the Fitzgerald River National Park. Unpublished report. Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank many people that provided valable assistance and input into the project. Sarah Barrett, Anita Barnett, Karen Rusten, Deon Utber, Sarah Comer, Charlotte Mueller, Jason Peters, Roger Cunningham, Chris Rathbone, Carol Ebbett and Janet Newell provided assisstance with fieldwork. Carol Wilkins, Rachel Meissner, Juliet Wege, Barbara Rye, Mike Hislop, Cate Tauss, Rob Davis, Greg Keighery, Nathan McQuoid and Marco Rossetto assissted with plant identification. Coralie Hortin, Karin Baker and many other members of the Albany Wildflower society helped with vouchering of plant specimens. 2 Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. -

ALINTA DBNGP LOOPING 10 Rehabilitation Management Plan

DBNGP (WA) Nominees Pty Ltd DBNGP LOOPING 10 Rehabilitation Management Plan ALINTA DBNGP LOOPING 10 Rehabilitation Management Plan November 2005 Ecos Consulting (Aust) Pty Ltd CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ 1 2 REHABILITATION REVIEW............................................................ 1 2.1 REHABILITATION OBJECTIVES ............................................................... 2 3 EXISTING VEGETATION ................................................................. 2 3.1 FLORA AND VEGETATION...................................................................... 2 3.2 VEGETATION STUDIES ........................................................................... 4 3.2.1 Study Method ............................................................................... 4 3.2.2 Study Results ................................................................................ 7 3.3 OTHER ENVIRONMENTAL VALUES ...................................................... 10 4 REHABILITATION STRATEGY..................................................... 11 5 REHABILITATION METHODS ..................................................... 11 5.1 WEED MANAGEMENT.......................................................................... 11 5.2 DIEBACK (PHYTOPHTHORA CINNAMOMI) MANAGEMENT .................... 11 5.3 PRIORITY AND RARE FLORA MANAGEMENT ........................................ 12 5.4 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT ................................................................... 13 5.5 -

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia By: D.A. Cumming, D. Garratt, M. McCarthy, A. WoICe With <.:unlribuliuns from Albany Seniur High Schoul. M. Anderson. R. Howard. C.A. Miller and P. Worsley Octobel' 1995 @WAUUSEUM Report: Department of Matitime Archaeology, Westem Australian Maritime Museum. No, 98. Cover pholograph: A view of Halllelin Bay in iL~ heyday as a limber porl. (W A Marilime Museum) This study is dedicated to the memory of Denis Arthur Cuml11ing 1923-1995 This project was funded under the National Estate Program, a Commonwealth-financed grants scheme administered by the Australian HeriL:'lge Commission (Federal Government) and the Heritage Council of Western Australia. (State Govenlluent). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Heritage Council of Western Australia Mr lan Baxter (Director) Mr Geny MacGill Ms Jenni Williams Ms Sharon McKerrow Dr Lenore Layman The Institution of Engineers, Australia Mr Max Anderson Mr Richard Hartley Mr Bmce James Mr Tony Moulds Mrs Dorothy Austen-Smith The State Archive of Westem Australia Mr David Whitford The Esperance Bay HistOIical Society Mrs Olive Tamlin Mr Merv Andre Mr Peter Anderson of Esperance Mr Peter Hudson of Esperance The Augusta HistOIical Society Mr Steve Mm'shall of Augusta The Busselton HistOlical Societv Mrs Elizabeth Nelson Mr Alfred Reynolds of Dunsborough Mr Philip Overton of Busselton Mr Rupert Genitsen The Bunbury Timber Jetty Preservation Society inc. Mrs B. Manea The Bunbury HistOlical Society The Rockingham Historical Society The Geraldton Historical Society Mrs J Trautman Mrs D Benzie Mrs Glenis Thomas Mr Peter W orsley of Gerald ton The Onslow Goods Shed Museum Mr lan Blair Mr Les Butcher Ms Gaye Nay ton The Roebourne Historical Society. -

V:\GIS3-Systems\Op Mapping

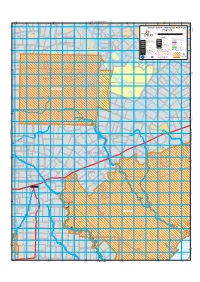

118°50'00"E 119°10'00"E 670 000mE 680 000mE 119°00'00"E 690 000mE 700 000mE Joins Dragon Rocks 710 000mE R 20350 119°20'00"E 720 000mE 730 000mE 119°30'00"E 740 000mE R 20350 R 48436 33°20'00"S Western Shield - 1080 Poison Risk Areas Dunn Rock NR Dunn Rock NR 6 310 000mN 6 310 000mN R 36445 FitzgeraldR 36445 R 20349 Map current as at March 2014 33°20'00"S kilometres 0 2 4 6 8 10 kilometres Lake Bryde NR* A 29020 HORIZONTAL DATUM : GEOCENTRIC DATUM OF AUSTRALIA 1994 (GDA94) - ZONE 50 Dunn Rock NR R 36445 Lake Bryde NR* Shire of Lake Grace A 29021 WHEATBELT LEGEND Department - Managed Land Other Land Categories Management boundaries (includes existing and proposed) Other Crown reserves Shire of State forest, timber reserve, Local Government Authority boundary miscellaneous reserves and land held under title by the CALM Executive Body REGION *Unallocated Crown land (UCL) DPaW region boundary Great Southern National park District *Unmanaged Crown reserves (UMR) DPaW district boundary (not vested with any authority) Nature reserve Trails Private property, Pastoral leases Bibbulmun Track Conservation park Munda Biddi Trail (cycle) Lake Magenta NR R 25113 Cape to Cape Walk Track CALM Act sections 5(1)(g), 5(1)(h) reserve *The management and administration of UCL and UMR's by & miscellaneous reserve DPaW and the Department of Lands respectively, is agreed to by the parties in a Memorandum of Understanding. Western Shield Former leasehold & CALM Act sections DPaW has on-ground management responsibilty. -

Waterloo Urban and Industrial Expansion Flora and Fauna Survey

Shire of Dardanup Waterloo Urban and Industrial Expansion Flora and Fauna Survey March 2015 Executive summary This report is subject to, and must be read in conjunction with, the limitations set out in Section 1.4 and the assumptions and qualifications contained throughout the Report. The Greater Bunbury Strategy and Structure Plan identified a potential significant urban expansion area located to the east of the Eaton locality and an industrial expansion area in Waterloo, in the Shire of Dardanup. The Shire of Dardanup (the Shire) and the Department of Planning have commenced preparation of District Structure Plans (DSP) for the urban expansion area and the industrial expansion area. The DSP will be informed by several technical studies including flora and fauna surveys. The Shire has commissioned GHD Pty Ltd (GHD) to undertake a flora and fauna survey and reporting for the Project. The Project Area is situated in the locality of Waterloo in the Shire of Dardanup. The Project Area includes the urban development area to the north of the South- west Highway (SWH) and the industrial development area to the south of the SWH. GHD undertook a desktop assessment of the Project Area and a flora and fauna field assessment with the first phase conducted from 13 to 14 August, 2014 and the second phase conducted from 29 to 31 October 2014. The purpose of this assessment was to identify the parts of the Project Area that have high, moderate and low ecological values so that the Shire can develop the DSP in consideration of these ecological values. This assessment identified the biological features of the Project Area and the key results are as follows.