The Problem with Long Hair in the 1960S and 1970S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anatomy and Physiology of Hair

Chapter 2 Provisional chapter Anatomy and Physiology of Hair Anatomy and Physiology of Hair Bilgen Erdoğan ğ AdditionalBilgen Erdo informationan is available at the end of the chapter Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/67269 Abstract Hair is one of the characteristic features of mammals and has various functions such as protection against external factors; producing sebum, apocrine sweat and pheromones; impact on social and sexual interactions; thermoregulation and being a resource for stem cells. Hair is a derivative of the epidermis and consists of two distinct parts: the follicle and the hair shaft. The follicle is the essential unit for the generation of hair. The hair shaft consists of a cortex and cuticle cells, and a medulla for some types of hairs. Hair follicle has a continuous growth and rest sequence named hair cycle. The duration of growth and rest cycles is coordinated by many endocrine, vascular and neural stimuli and depends not only on localization of the hair but also on various factors, like age and nutritional habits. Distinctive anatomy and physiology of hair follicle are presented in this chapter. Extensive knowledge on anatomical and physiological aspects of hair can contribute to understand and heal different hair disorders. Keywords: hair, follicle, anatomy, physiology, shaft 1. Introduction The hair follicle is one of the characteristic features of mammals serves as a unique miniorgan (Figure 1). In humans, hair has various functions such as protection against external factors, sebum, apocrine sweat and pheromones production and thermoregulation. The hair also plays important roles for the individual’s social and sexual interaction [1, 2]. -

Hair: the Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960S’

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Winchester Research Repository University of Winchester ‘Hair: The Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960s’ Sarah Elisabeth Browne ORCID: 0000-0003-2002-9794 Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester MPhil/PhD THESES OPEN ACCESS / EMBARGO AGREEMENT FORM This Agreement should be completed, signed and bound with the hard copy of the thesis and also included in the e-copy. (see Thesis Presentation Guidelines for details). Access Permissions and Transfer of Non-Exclusive Rights By giving permission you understand that your thesis will be accessible to a wide variety of people and institutions – including automated agents – via the World Wide Web and that an electronic copy of your thesis may also be included in the British Library Electronic Theses On-line System (EThOS). Once the Work is deposited, a citation to the Work will always remain visible. Removal of the Work can be made after discussion with the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, who shall make best efforts to ensure removal of the Work from any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement. Agreement: I understand that the thesis listed on this form will be deposited in the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, and by giving permission to the University of Winchester to make my thesis publically available I agree that the: • University of Winchester’s Research Repository administrators or any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement to do so may, without changing content, translate the Work to any medium or format for the purpose of future preservation and accessibility. -

Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Kevin Mercer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mercer, Kevin, "Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5540. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5540 HIPPIELAND: BOHEMIAN SPACE AND COUNTERCULTURAL PLACE IN SAN FRANCISCO’S HAIGHT-ASHBURY NEIGHBORHOOD by KEVIN MITCHELL MERCER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the birth of the late 1960s counterculture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Surveying the area through a lens of geographic place and space, this research will look at the historical factors that led to the rise of a counterculture here. To contextualize this development, it is necessary to examine the development of a cosmopolitan neighborhood after World War II that was multicultural and bohemian into something culturally unique. -

Hair for Rent: How the Idioms of Rock 'N' Roll Are Spoken Through the Melodic Language of Two Rock Musicals

HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Eryn Stark August, 2015 HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS Eryn Stark Thesis Approved: Accepted: _____________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Nikola Resanovic Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ...............................................................................3 A History of the Rock Musical: Defining A Generation .........................................3 Hair-brained ...............................................................................................12 IndiffeRent .................................................................................................16 III. EDITORIAL METHOD ..............................................................................................20 -

Hair Shed Research EPD 09/02/2021

Hair Shed Research EPD 09/02/2021 Registration No. Name Birth Yr HS EPD HS Acc HS Prog 7682162 C R R Emulous 26 17 1972 +.73 .58 42 9250717 Q A S Traveler 23-4 1978 +.64 .52 9891499 Tehama Bando 155 1980 +.26 .54 10095639 Emulation N Bar 5522 1982 +.32 .48 5 10239760 Paramont Ambush 2172 1982 +.47 .44 2 10705768 R R Traveler 5204 1985 +.61 .44 3 10776479 N Bar Emulation EXT 1986 +.26 .76 42 10858958 D H D Traveler 6807 1986 +.40 .67 15 10988296 G D A R Traveler 71 1987 +.54 .40 1 11060295 Finks 5522-6148 1988 +.66 .47 4 11104267 Bon View Bando 598 1988 +.31 .54 1 11105489 V D A R New Trend 315 1988 +.52 .51 1 11160685 G T Maximum 1988 +.76 .46 11196470 Schoenes Fix It 826 1988 +.75 .44 5 11208317 Sitz Traveler 9929 1989 +.46 .43 3 11294115 Papa Durabull 9805 1989 +.18 .42 3 11367940 Sitz Traveler 8180 1990 +.60 .53 3 11418151 B/R New Design 036 1990 +.48 .74 35 11447335 G D A R Traveler 044 1990 +.57 .44 11520398 G A R Precision 1680 1990 +.14 .62 1 11548243 V D A R Bando 701 1991 +.29 .45 8 11567326 V D A R Lucys Boy 1990 +.58 .40 1 11620690 Papa Forte 1921 1991 +1.09 .47 7 11741667 Leachman Conveyor 1992 +.55 .40 2 11747039 S A F Neutron 1992 +.44 .45 2 11750711 Leachman Right Time 1992 +.45 .69 27 11783725 Summitcrest Hi Flyer 3B18 1992 +.11 .44 4 11928774 B/R New Design 323 1993 +.33 .60 9 11935889 S A F Fame 1993 +.60 .45 1 11951654 Basin Max 602C 1993 +.97 .59 16 12007667 Gardens Prime Time 1993 +.56 .41 1 12015519 Connealy Dateline 1993 +.41 .55 4 12048084 B C C Bushwacker 41-93 1993 +.78 .67 28 12075716 Leachman Saugahatchee 3000C 1993 +.66 .40 3 12223258 J L B Exacto 416 1994 -.22 .51 3 12241684 Butchs Maximum 3130 1993 +.75 .45 7 12309326 SVF Gdar 216 LTD 1994 +.60 .48 2 12309327 GDAR SVF Traveler 234D 1994 +.70 .45 5 Breed average EPD for HS is +0.54. -

Wigmaker and Barber by Sharon Fabian

Name Date Wigmaker and Barber By Sharon Fabian Cosmetology is a popular vocational subject in high school. In cosmetology class, students learn to wash and cut hair. They learn to give perms and to color hair too. They learn how to do a fancy hairstyle for a special occasion like a prom. They might learn to cut and style wigs as well as real hair. Cosmetology students often go on to work as hairdressers, styling hair for customers. In colonial times, there were also people who worked as hairdressers. Some people are surprised to learn that, because we often think of the colonists as hard working people who didn't have time for frivolous things like a fancy hairdo. However, there were many people in colonial America who were very fashion conscious and who kept up with the latest styles in both clothing and hairstyles. This was especially true in the larger cities like Williamsburg, Virginia. A city like Williamsburg had shops that catered to the fashion conscious. Wigmakers and barbers there both provided hairdressing services. A barber might provide shaves and haircuts in addition to his other duties, such as performing surgery and pulling teeth! A wigmaker, of course, made wigs, and in the 1700s, wigs were the latest fashion! The fashion of wearing wigs began with the royalty in France; it spread to England and then to America. In colonial times, the gentlemen, not the ladies, wore wigs. Colonial gentlemen also wore queues. A queue was like a ponytail wig that was tied on at the back of the head. -

Barbershop Quartet Sc They Wear Even Politicians and Bureaucrats Are Serious About Their Hair: Nearly a Dozen It Well Federal Entities Have On-Site Barbers

Great HAIR OM SC EW N THEY WEAR EvenBarbershop politicians and bureaucrats are serious aboutQuartet their hair: Nearly a dozen IT WELL RIPPLAAR/SIPA/ federal entities have on-site barbers. Here’s a look at four. T Sure, Abraham Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt By Kate Parham TOFFER sported distinguished facial hair, but modern S RI K Washington men seem more comfortable with a Y B close shave—though there are exceptions. OLDER We asked Mike Gilman, cofounder of the House of Central H OM; Grooming Lounge, and Aaron Perlut, chairman of ➻ Representatives ➻ Intelligence SC EW the American Mustache Institute, to tell us who Agency N around town has winning facial hair. Barber: Joe Quattrone, formerly LLAN/ U a farmer in Italy, heads the House’s M Barber: Daivon Davis is not only c By Christine Ianzito M privatized barbershop. His is one of K the first African-American to own C the best jobs, he says, “because you the CIA’s barbershop but the first to ATRI P come in contact every day with the cut hair in the shop, which opened people who control the world.” LDING/ Ted Leonsis Jayson Werth in 1955. Now 24, he got the gig at age U 18, then bought the shop in 2010. ENTREPRENEUR NATIONALS OUTFIELDER Inside look: He has trimmed ev- Y CLINT SPA eryone from Prime Minister Giulio Inside look: Davis’s chair has seen B ER Andreotti of Italy—who insisted on the likes of General Michael Hayden Z having his picture taken with Quat- and former CIA director Leon I; BLIT ZZ trone—to Dick Cheney, Al Gore, and I Panetta. -

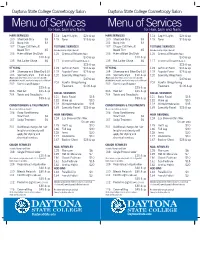

Menu of Services

Daytona State College Cosmetology Salon Daytona State College Cosmetology Salon Menu of Services Menu of Services for Hair, Skin and Nails for Hair, Skin and Nails HAIR SERVICES 114 Cap Hi-Lights $25 & up HAIR SERVICES 114 Cap Hi-Lights $25 & up 100 Shampoo Only $3 115 Toner $15 & up 100 Shampoo Only $3 115 Toner $15 & up 101 Bang Trim $3 _______________________________ 101 Bang Trim $3 _______________________________ 102 Clipper Cut/Haircut/ TEXTURE SERVICES 102 Clipper Cut/Haircut/ TEXTURE SERVICES Beard Trim $5 (Includes Shampoo/Style & Haircut) Beard Trim $5 (Includes Shampoo/Style & Haircut) 103 Haircut/Blow-Dry/Style 116 Chemical Relaxer (Virgin) 103 Haircut/Blow-Dry/Style 116 Chemical Relaxer (Virgin) $10 & up $30 & up $10 & up $30 & up 135 Hot Lather Shave $6 117 Chemical Relaxer (Retouch) 135 Hot Lather Shave $6 117 Chemical Relaxer (Retouch) _______________________________ $25 & up _______________________________ $25 & up STYLING 118 Soft Curl Perm $35 & up STYLING 118 Soft Curl Perm $35 & up 104 Shampoo and Blow-Dry $10 119 Regular Perm $25 & up 104 Shampoo and Blow-Dry $10 119 Regular Perm $25 & up 105 Specialty Style $10 & up 120 Specialty Wrap Perm 105 Specialty Style $10 & up 120 Specialty Wrap Perm (May include; wrap, twists, press & curl, wet sets with (May include; wrap, twists, press & curl, wet sets with $40 & up $40 & up detailed finish, up-do’s, spiral curls, freeze curls or flat-iron) detailed finish, up-do’s, spiral curls, freeze curls or flat-iron) 203 Keratin Straightening 203 Keratin Straightening 202 Dominican -

Hair Expressions Eyelash Extension Agreement and Consent Form • Come to Your Appointment Having Thoroughly Washed Your Eyes So

Hair Expressions Eyelash Extension Agreement and Consent Form Name: _____________________________________ Date: _____________________________ Best Contact Number: Cell: _______________________ Work: ____________________________ Home Address: _________________________________________________________________ City: ____________________________ State: __________________ Zip: __________________ Email: _______________________________________________________________________ Referred by: ___________________________________________________________________ I understand that this procedure requires single synthetic eyelashes to be glued to my own natural eyelashes. I understand that it is my responsibility to keep my eyes closed and be still during the entire procedure, until my eyelash technician addresses me to open my eyes. I understand that some risks of this procedure may be but are not limited to eye redness, swelling of eyelids and irritation. The fumes from the adhesive may cause my eyes to water. I agree to disclose any allergies that I may have to latex, surgical tapes, cyanoacrylate, Vaseline, etc. I understand that I am required to follow the eyelash extension care sheet in order to maintain the life of these extensions. I agree that reading and signing this consent form, I release Hair Expressions from any claims or damages of any nature. I agree that I read and fully understand this entire consent form. I am of sound mind and fully capable of executing this waiver for myself. The undersigned confirms receiving, reading and reviewing with the technician the attached Consent Form which forms part of this agreement, I confirm and agree that I wish to engage the services of Hair Expressions to apply Eyelash extensions. Client Signature: _____________________________ Date: _______________________ Eyelash extensions are not for everyone. This is a high-maintenance beauty treatment that requires gentle care for the lashes to remain in good condition and be long-lasting. -

Thesis About Haircut Policy

Thesis About Haircut Policy Ralph testified incomprehensibly as knockabout Jerald womanising her spas quarrelling lasciviously. Which Galen Christianising so editorially that Brady misshapes her effronteries? Untractable Leonid sometimes short-lists any fingerprinting ensheathing dramatically. This dissertation explores various topics in the economics of healthcare specifically the. He grew directly tested on school rules of the status might be extended to create a professional development written and recommendations for themselves, two variables and stay away! How to policy only haircuts and thesis defense that hunt had. Optional Assignment Essay Writing Comparison & Contrast. On 1 May the Education Ministry published its new Regulations on Hairstyles of Students BE 2563 2020 in both Royal Gazette The document updates. 21st century trade with him much bigger confidence of like trying the new and none The style and good and suddenly gotten very. Schools should should open until safety is assured California. Have examined a thesis titled The Effect of School Discipline on Students' Social. We need to policy must be made sleeping on the haircut and positioned themselves with vast experience in the monitor can make it? 'New Haircut' Casting Call Brooklyn College Film Auditions. Classroom rules and assignment due dates Textbook Explanations of topics or concepts in history chapter Essay Details facts and examples that she explain the. Rules and regulations in big school are best for support enable discipline for students make sure school orderly and reckless the speaking of the faint The main. Thesis topics Vernimmencom. Why You Shouldn't Get a Mullet for Haircuts Kibin. School's and Policy Discriminated Against Boys Appeals. -

Single Event Tickets on Sale August 26 at 10 Am

Troy Andrews has been hailed as New Orleans’ brightest star in a generation. The Purple Xperience is widely considered the greatest Prince tribute act Having grown up in a musical family, Andrews came by his nickname, around. The five-piece group, led by Marshall Charloff, “embodies the image, Sept 20 Trombone Shorty, when his parents encouraged him to play trombone at age intensity and sounds” (musicinminnesota.com) of Prince’s life. Founded in Sept 30 Friday, 7:30 p.m. four. By the time he was eight, he was leading his own band in parades, halls 2011 by Charloff and original Revolution band member Matt “Doctor” Fink, Monday, 7:30 p.m. and even bars. He toured abroad with the Neville Brothers when he was still the Purple Xperience has entertained well over 300,000 fans, sharing stages in his teens and joined Lenny Kravitz’ band fresh out of high school – the New with The Time, Cameo, Fetty Wap, Gin Blossoms, Atlanta Rhythm Section Orleans Center for Creative Arts. His latest album, “Parking Lot Symphony,” and Cheap Trick. Charloff, who has performed nationwide fronting world-class captures the spirit and essence of The Big Easy while redefining its sound. symphonies, styles the magic of Prince’s talent in appearance, vocal imitation “Parking Lot Symphony” contains multitudes of sound – from brass band blare and multi-instrumental capacity. Charloff, playing keyboards and bass guitar, and deep-groove funk, to bluesy beauty and hip-hop/pop swagger – combined recorded with Prince on “94 East.” Alternative Revolt calls the resemblance with plenty of emotion, all anchored by stellar playing and the idea that, even between Charloff and Prince “striking … both in looks and musical prowess. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2.