A Study on the Traditionalism of В€Œtrot∕ В€“ Focused on Yi Nanyз'ngв€™S В€Œtears of Mokpв€™Oв

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ismert K-Pop Előadók Dalai 5

Ismert előadók híresebb dalai - 5 Írta: Edina holmes Mi is az a K-pop? VIII. Zene k-pop 094 Ezzel a résszel befejezzük az ismerkedést a k-pop dalokkal az első generációtól mostanáig. A változatosság érdekében nemcsak egy generációt veszünk végig a cikkben, hanem az összesből sze- mezgetünk időrendi sorrendben. Vágjunk is bele! A dalokat meghallgathatjátok az edinaholmes. com-on előadók szerinti lejátszólistákban. Psy Aktív évek: 2001-napjainkig Ügynökség: P Nation Híresebb dalai: Bird, The End, Champion, We Are The One, Delight, Entertainer, Right Now, Shake It, Gangnam Style, Gentleman, Daddy, Napal Baji, New Face, I Luv It Big Bang Sechs Kies Tagok száma: 4 J. Y. Park Tagok száma: 4 Aktív évek: 2006-napjainkig Aktív évek: 1994-napjainkig Aktív évek: 1997-2000; 2016-napjainkig Lee Hyori Ügynökség: YG Ügynökség: JYP Ügynökség: YG Aktív évek: 2003-napjainkig Híresebb dalaik: Lies, Last Farewell, Haru Haru, Híresebb dalai: Don’t Leave Me, Elevator, Híresebb dalaik: School Byeolgok, Ügynökség: Esteem Sunset Glow, Tonight, Love Song, Blue, Bad Boy, She Was Pretty, Honey, Kiss, Your House, Pom Saeng Pom Sa, Chivalry, Road Fighter, Híresebb dalai: 10 Minutes, Toc Toc Toc, Fantastic Baby, Monster, Loser, Bae Bae, Someone Else, You’re The One, Who’s Your Reckless Love, Couple, Com’ Back, Hunch, U-Go-Girl, Swing, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Bang Bang Bang, If You, Let’s Not Fall In Love, Mama?, I’m So Sexy, Fever, When We Disco Three Words, Be Well, Something Special Miss Korea, Bad Girls, Seoul, Black Fxxk It, Last Dance, Flower Road AniMagazin Tartalomjegyzék △ Zene k-pop 095 Legendás K-pop zenék - vol 8. -

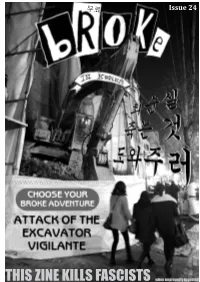

THIS ZINE KILLS FASCISTS When Improperly Ingested Letter from the Editor Table of Contents Well That Took a While

무료 Issue 24 THIS ZINE KILLS FASCISTS when improperly ingested Letter from the Editor Table of Contents Well that took a while. I’ve concluded it’s hard to motivate myself to 1. Cover write zines while I’m also working at a newspaper. Even if it’s “that” newspaper, it still lets me print a lot of crazy stuff, at least until I start 2. This Page pushing it too far. Issue 24 The last issue was starting to seem a little lazy, as I was recycling con- 3. Letters to the Editor June/Sept 2017 tent also published in the newspaper. For this issue I wanted to cut down on that, as well as on lengthy interviews. So we have a lot of smaller 4. Ash stories, and all sorts of other quick content. I interviewed a lot of people This zine has been published and sliced up their interviews into pieces here and there. I also filched a 5. Dead Gakkahs at random intervals for the lot of content from social media, mainly as PSAs. Think of it more as a past ten years. social media share/retweet, but on paper; hope no one’s pissed. 6. Pseudo & BurnBurnBurn There’s a page spread on Yuppie Killer memories I solicited way back Founders when Yuppie Killer had their last show. There’s also a similar spread on 7. WDI & SHARP Jon Twitch people’s memories of Hongdae Playground, where you can get a sense 8. Playground Paul Mutts of how radically the place has changed, as well as possibly the effect we had on it ourselves. -

Download Lagu After School Bang Japanl

Download Lagu After School Bang Japanl 1 / 4 Download Lagu After School Bang Japanl 2 / 4 3 / 4 Download Lagu Various Artists - Doctors OST . ... (Remixed by Planet Shiver) Rele Jan 11, 2009 · After School (First Single) - New School Girl. ... Nicknamed the "Oricon comet" for her success in Japan, she has released eight singles and ... SiSTAR , Wheesung , Younha 0 comments to “[Album] 2NE1 & Big Bang – YG In Da .... Download Lagu After School - Bang! (Japanese Ver.) MP3 Gratis [3.07 MB]. Download CEPAT dan MUDAH. Download lagu terbaru, gudang .... Download Lagu Korea - After School apk 1.0 for Android. Korean KPOP a collection of songs that dinaynyikan by After School.. Bang (Japan Version) - After School | Nghe nhạc hay online mới nhất chất lượng ... Các bạn có thể nghe, download (tải nhạc) bài hát bang (japan version) mp3, .... [2011.08.17] Bang! (Japanese Version) - Single [MP3 320kbps]. gdrive / mail ru. [2011.11.23] Diva (Japan Version) - Single [iTunes Plus ACC .... Shop Korean After School "Bang!" Wind stage costume size M ~ cosplay costume costume party for (japan import). Free delivery and returns on eligible orders of .... Free Download Kpop Music with High Quality MP3, iTunes Plus AAC M4A. ... Download [single] Got7 – Love Train [japanese] via k2nblog. ... Also a fangirl of Korean boy band BTS [Bangtan Boys] and love the seven idiots (BTS' ... 100% 2AM 2NE1 2PM 4MINUTE 9 MUSES A-Jax A- Prince Actor After School Ailee AKMU .... Download Lagu After School First Love Mp3. The index of Download Lagu After ... Shine · Shine (Video Lirik) · Lucky Girl · Week · Shh (Dance Version) · Bang! ... Stand up to A teenager in Japan who felt disgraced because he ... -

Beyond the Scene, Literally

Beyond the Scene, Literally ACADEMIC ARTICLE: ESSAY Loraine Cao Loraine is a student from the U.S. studying neuroscience on a pre-medical track at The University of Texas at Dallas. (United States) ABSTRACT BTS have several factors that have contributed to their exponentially rising popularity, but the most outstanding factor is the deeper message that they deliver through their music. Released in 2017, “Spring Day” is BTS’s longest-charting track. It goes beyond the typical love song and its music video not only includes but transcends past aesthetics. A close visual analysis of the “Spring Day” music video leads one to find a profound message that is up to interpretation. It contains visual elements, appropriately accompanying lyrics, and literary references to Christian Boltanski’s No Man’s Land and Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas,” all of which lead to comfort in dealing with the loss of a loved one and the overarching concept of “you never walk alone.” KEYWORDS BTS, K-pop, “Spring Day,” video, interpretation, analysis, charts, “You Never Walk Alone” The music industry is an industry well known for its profitability and ever-growing variety of genres and artists. According to Watson (2019), the U.S. music industry alone generated approximately 20 billion dollars in revenue in 2018, which highlights the scale of music consumption and output in the U.S. However, several reports have also emphasized the oversaturation of the music industry. Additionally, genres such as jazz, pop, and country are some of the most popular and easily recognized styles, whereas genres such as K-pop or Korean pop still belong to the category of genres with niche listeners. -

Estereotipos Raciales Y De Género En El K-Pop: El Caso Español

UNIVERSIDAD DE VALLADOLID Máster en Música Hispana ESTEREOTIPOS RACIALES Y DE GÉNERO EN EL K-POP: EL CASO ESPAÑOL Trabajo Fin de Máster TERESA OLMEDO SEÑOR Realizado bajo la dirección del Prof. Dr. Iván Iglesias Iglesias Julio de 2018 Curso Académico 2017-2018 UNIVERSIDAD DE VALLADOLID Máster en Música Hispana ESTEREOTIPOS RACIALES Y DE GÉNERO EN EL K-POP: EL CASO ESPAÑOL Trabajo Fin de Máster TERESA OLMEDO SEÑOR Realizado bajo la dirección del Prof. Dr. Iván Iglesias Iglesias Julio de 2018 Curso Académico 2017-2018 El tutor La alumna ÍNDICE Listado de ilustraciones ..................................................................................................... 9 Introducción ................................................................................................................... 11 Presentación del tema y justificación .................................................................. 11 Objetivos .............................................................................................................. 13 Estado de la cuestión ........................................................................................... 14 Marco teórico ....................................................................................................... 19 Metodología y fuentes ......................................................................................... 22 Estructura del trabajo ........................................................................................... 23 1. Capítulo 1: Estereotipos de género ......................................................................... -

Facultad De Ciencias Sociales Y Jurídicas

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y JURÍDICAS GRADO EN COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Título: ESTUDIO DEL IMPACTO DE LA INDUSTRIA MUSICAL SURCOREANA EN OCCIDENTE A TRAVÉS DEL VIDEOCLIP TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO DE INVESTIGACIÓN BIBLIOGRÁFICA 2018/2019 Alumno: Adrián Salguero Vico Tutor: Vicente Javier Pérez Valero 1 ÍNDICE 1. Resumen / abstract …………………………………………………………….. 4 2. Palabras clave / keywords …………………………………………………….. 6 3. Introducción……………………………………………………………………….6 4. Hipótesis………………………………………………………………………….. 7 5. Objetivos…………………………………………………………………………..7 6. Estado de la cuestión y marco teórico…………………………………………8 1. Base y orígenes del fenómeno K-POP………………………………..8 2. Era dorada - Viralización y aparición de YouTube (2009-2015) 1. Videoclip y YouTube…………………………………………….10 2. La 2º generación del K-POP………………………………….. 12 3. Viralización y boom 2012……………………………………... 14 3. Estado actual – nuevos grupos y fórmulas (2015 – actualidad) 1. Expansión del fenómeno fan………………………………….. 17 2. Reconocimiento y expansión…………………………………. 19 3. Marcando la diferencia………………………………………… 20 7. Metodología……………………………………………………………………… 24 8. Resultados……………………………………………………………………….. 25 9. Conclusiones…………………………………………………………………….. 29 10.Bibliografía………………………………………………………………………. 32 11.Anexos 1. Encuesta sobre consumo musical y de K-POP………………………34 2. Resultados de la encuesta…………………………………………….. 51 3. Tabla – análisis videoclips………………………………………………61 2 TABLAS Tabla 1 – Resumen de videoclips visionados…………………………………25 Tabla 2 – Resultados de encuesta……………………………………………..26 GRÁFICOS Gráfico -

Catching the K-Pop Wave: Globality in the Production, Distribution, and Consumption of South Korean Popular Music Sarah Leung

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2012 Catching the K-Pop Wave: Globality in the Production, Distribution, and Consumption of South Korean Popular Music Sarah Leung Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Leung, Sarah, "Catching the K-Pop Wave: Globality in the Production, Distribution, and Consumption of South Korean Popular Music" (2012). Senior Capstone Projects. 149. http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/149 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Catching the K-Pop Wave: Globality in the Production, Distribution, and Consumption of South Korean Popular Music Sarah Leung Media Studies Senior Thesis Thesis Adviser: Tarik Elseewi April 20, 2012 Chapter List: I. Going with the Flow: K-Pop and the Hallyu Wave…….…………………………………2 1. Introduction…………………………………………………..……………………2 2. So What is K-Pop? Local vs. Global Identities……………...…………….…….10 II. Making the Band: K-Pop Production………………….…….…….….….………………25 1. The Importance of Image……………………………………………..………….25 2. Idol Recruitment, Training, and Maintenance………………………….…..……28 III. Around the World: Patterns of K-Pop Consumption…………….….….…….………….34 1. Where is K-Pop being Consumed? …………………….….…………………….34 2. Interculture, Transnational Identity, and Resistance……...……………….……..42 IV. Crazed! The “Pop” in K-Pop………………………………………………………….…48 1. H.O.T.? Issues of Gender and Sexuality in K-Pop’s Appeal……..…..………….48 2. Fan Culture and Media Convergence………………...……………………….…69 V. Conclusions……………………………………………..………………………….…….77 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………85 Leung 1 I. -

ANIME OP/ED (TV-Versio) Japahari Net - Retsu No Matataki Maximum the Hormone - ROLLING 1000 Toon

Air Master ANIME OP/ED (TV-versio) Japahari Net - Retsu no matataki Maximum the Hormone - ROLLING 1000 tOON 07 Ghost Ajin Yuki Suzuki - Aka no Kakera flumpool - Yoru wa Nemureru kai? Mamoru Miyano - How Close You Are 91 Days Angela x Fripside - Boku wa Boku de atte ELISA - Rain or Shine TK from Ling Tosite Sigure - Signal Amanchu Maaya Sakamoto - Million Clouds 11eyes Asriel - Sequentia Ange Vierge Ayane - Arrival of Tears Konomi Suzuki - Love is MY RAIL 3-gatsu no Lion Angel Beats BUMP OF CHICKEN - Answer Aoi Tada - Brave Song .dot-Hack Lisa - My Soul Your Beats See-Saw - Yasashii Yoake Girls Dead Monster - My Song Bump of chicken - Fighter Angelic Layer .hack//g.u Atsuko Enomoto - Be my Angel Ali Project - God Diva HAL - The Starry sky .hack//Liminality Anime-gataris See-Saw - Tasogare no Umi GARNiDELiA - Aikotoba .hack//Roots Akagami no Shirayuki hime Boukoku Kakusei Catharsis Saori Hayami - Yasashii Kibou eyelis - Kizuna ni nosete Abenobashi Mahou Shoutengai Megumi Hayashibara - Anata no kokoro ni Akagami no Shirayuki hime 2nd season Saori Hayami - Sono Koe ga Chizu ni Naru Absolute Duo eyelis - Page ~Kimi to Tsuzuru Monogatari~ Nozomi Yamamoto & Haruka Yamazaki - Apple Tea no Aji Akagi Maximum the Hormone - Akagi Accel World May'n - Chase the World Akame ga Kill Sachika Misawa - Unite. Miku Sawai - Konna Sekai, Shiritakunakatta Altima - Burst the gravity Rika Mayama - Liar Mask Kotoko - →unfinished→ Sora Amamiya - Skyreach Active Raid Akatsuki no Yona AKINO with bless4 - Golden Life Shikata Akiko - Akatsuki Cyntia - Akatsuki no hana -

Kpop Album Checklist My Bank Account Says Nope but My Boredness Told Me to Make It Babes Xoxo

KPOP ALBUM CHECKLIST MY BANK ACCOUNT SAYS NOPE BUT MY BOREDNESS TOLD ME TO MAKE IT BABES XOXO 2NE1 - First mini album 2NE1- Second mini album 2NE1 - To anyone 2NE1 - Crush 2NE1 - Nolza (Japan) 2NE1 - Collection (Japan) 2NE1 - Crush (Japan) 3YE - Do my thang (Promo) 3YE - Out of my mind (Promo) 3YE - Queen (Promo) 4MINUTE - 4 Minutes left 4MINUTE - For muzik 4MINUTE - Hit your heart 4MINUTE - Heart to heart= 4MINUTE - Volume up 4MINUTE - Name is 4minute 4MINUTE - 4minute world 4MINUTE - Crazy 4MINUTE - Act 7 4MINUTE - Diamond (Japan) 4MINUTE - Best of 4minute (Japan) 4TEN - Jack of all trades 4TEN- Why (Promo) 9MUSES - Sweet rendevouz 9MUSES - Wild 9MUSES - Drama 9MUSES - Lost (OOP) 9MUSES- Muses diary part 2 : Identity 9MUSES - Muses diary part 3 : Love city 9MUSES - 9muses S/S edition 9MUSES - Lets have a party 9MUSES - Dolls 9MUSES - Muses diary (Promo) AFTERSCHOOL - Virgin AFTERSCHOOL - New schoolgirl (OOP) AFTERSCHOOL - Because of you AFTERSCHOOL - Bang (OOP) AFTERSCHOOL - Red/Blue (OOP) AFTERSCHOOL - Flashback (OOP) AFTERSCHOOL - First love AFTERSCHOOL - Playgirlz (Japan) AFTERSCHOOL - Dress to kill (Japan) AFTERSCHOOL - Best (Japan) AILEE - Vivid AILEE - Butterfly AILEE - Invitation AILEE- Doll house AILEE - Magazine AILEE - A new empire AILEE - Heaven (Japan) AILEE - U&I (Japan) ALEXA - Do or die (Japan) ANS - Boom Boom (Promo) ANS - Say my name (Promo) AOA - Angels knock AOA - Short hair (OOP) AOA - Like a cat AOA - Heart attack AOA - Good luck AOA - Bingle bangle AOA - New moon AOA - Angels story AOA - Wanna be AOA - Moya AOA -

Vol.005 FTISLAND / John-Hoon Vol.006 超新星 / MBLAQ Vol.007

※取次さま順次搬入 ※調整が入る可能性がございます 電話(03)6367-8095 ※品切の際、受注保留はしておりませんのでご了承ください。 更新:2017年8月8日 書誌名 表紙タレント / 裏表紙タレント 発売日 コード 本体 ご注文数 vol.005 FTISLAND / John-Hoon 2011/5/21 20846-7/4 ¥ 933 ピンナップ:両面ともFTISLAND 2PM / Jphn-Hoon / MBLAQ / ZE:A / イ・ジフン / パク・ジョンミン / キム・キュジョン / WONBIN / SHU-I / Apeace / CODE-V / チャン・グンソク / ソン・ジュンギ ユ・アイン パク・ミニョン ほか 冊 vol.006 超新星 / MBLAQ 2011/7/22 20846-9/3 ¥ 933 ピンナップ:両面とも超新星 SHINee / MBLAQ / パク・シフ / キム・ドンワン / ユン・シユン / ヒョヌ / キム・スヒョン / チュウォン / イ・ジョンソク / チ・ チャンウク / ホン・ジョンヒョン / U-KISS / キム・ヒョンジュン / Secret / SHU-I 他 冊 vol.007 2AM / ウォンビン 2011/9/22 20846-11/5 ¥ 933 ピンナップ:2AM / TEENTOP 2PM / T-ARA / U-KISS / ZE:A / TEENTOP / SHU-I / ギュリ / ソンジェ / イ・ホンギ / ウォンビン / クォン・サンウ / キム・ ヒョンジュン / イ・ミンホ / チョン・ジョンミョン / チョン・ギョウン ほか 冊 vol.009 INFINITE / パク・シフ 2012/1/21 20846-3/3 ¥ 933 ピンナップ:両面ともINFINITE AFTERSCHOOL / 大国男児 / Girl's Day / Block.B / SHU-I / Apeace / パク・シフ / カン・ジファン / ANDY / ジヒョク / SE7EN / 2AM / U-KISS / 小田切ジョー&チャン・ドンゴン / GACKT 冊 vol.010 イ・スンギ / イ・ミンホ 2012/2/2 20846-4/5 ¥ 933 パク・ミニョン / ク・ハラ / Jphn-Hoon / 2AM / AFTERSCHOOL / Secret / JAY PARK / ALEX / SM☆SH / N-TRAIN / N-sonic / SHU-I / Apeace / チョ・ヒョンジェ / チョン・イル / イ・ジャンウ / チャン・ナラ 他 冊 vol.011 U-KISS / IU 2012/3/22 20846-5/5 ¥ 933 ピンナップ: U-KISS / IU T-ARA / John-Hoon / ZE:A / 大国男児 / SHU-I / Apeace / イ・ジュンギ / チェ・シウォン / チョン・ジヌン / チソン / キム・ ヒョンジュン / チャ・スンウォン / コン・ヒョジン / ハ・ジウォン ほか 冊 vol.012 イ・ジュンギ / INFINITE 2012/5/22 20846-7/5 ¥ 933 ピンナップ:イ・ジュンギ / INFINITE INFINITE / SE7VEN / 2AM / T-ARA / 大国男児 / ジヨン&ゴニル / イ・ジヌク / ベ・スビン / BIGBANG / Nana / SHU-I / MYNAME / CODE-V / Apeace / チョン・イル / ソ・ジソブ -

Bankruptcy Forms for Non-Individuals, Is Available

Fill in this information to identify your case: United States Bankruptcy Court for the: WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS Case number (if known) Chapter 11 Check if this an amended filing Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy 4/19 If more space is needed, attach a separate sheet to this form. On the top of any additional pages, write the debtor's name and case number (if known). For more information, a separate document, Instructions for Bankruptcy Forms for Non-Individuals, is available. 1. Debtor's name A'GACI, L.L.C. 2. All other names debtor used in the last 8 years DBA Won Management, LLC Include any assumed DBA O'Shoes names, trade names and DBA Boutique Five doing business as names 3. Debtor's federal Employer Identification 74-3009604 Number (EIN) 4. Debtor's address Principal place of business Mailing address, if different from principal place of business 4958 Stout Dr., Ste. 113 San Antonio, TX 78219-4400 Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code P.O. Box, Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code Bexar Location of principal assets, if different from principal County place of business Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code 5. Debtor's website (URL) www.agacistore.com 6. Type of debtor Corporation (including Limited Liability Company (LLC) and Limited Liability Partnership (LLP)) Partnership (excluding LLP) Other. Specify: Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy page 1 Debtor A'GACI, L.L.C. Case number (if known) Name 7. Describe debtor's business A. Check one: Health Care Business (as defined in 11 U.S.C. -

Vol.005 FTISLAND / John-Hoon FTISLAND / John-Hoon Vol.006

※委託 ※取次さま順次搬入 ※調整が入る可能性がございます ※返品については基本受け付けておりません。 ※フェア展開等いただける際はご相談ください。 電話(03)6367-8095 2016927 ᭩ㄅྡ䢢⾲⣬儣児兗儬䢢䢱䢢⾲⣬儣児兗儬Ⓨ᪥ 儗兠儭 ᮏయ 傺ὀᩥᩘ vol.005 FTISLAND / John-Hoon 2011/5/21 20846-7/4 \ 933 ピンナップ:両面ともFTISLAND 2PM / Jphn-Hoon / MBLAQ / ZE:A / イ・ジフン / パク・ジョンミン / キム・キュジョン / WONBIN / SHU-I / Apeace / CODE-V / チャン・グンソク / ソン・ジュンギ ユ・アイン パク・ミニョン ほか vol.006 超新星 / MBLAQ 2011/7/22 20846-9/3 \ 933 ピンナップ:両面とも超新星 SHINee / MBLAQ / パク・シフ / キム・ドンワン / ユン・シユン / ヒョヌ / キム・スヒョン / チュウォン / イ・ジョンソク / チ・チャンウク / ホン・ジョンヒョン / U-KISS / キム・ヒョンジュン / Secret / SHU-I 他 vol.007 2AM / ウォンビン 2011/9/22 20846-11/5 \ 933 ピンナップ:2AM / TEENTOP 2PM / T-ARA / U-KISS / ZE:A / TEENTOP / SHU-I / ギュリ / ソンジェ / イ・ホンギ / ウォンビン / クォン・サンウ / キム・ ヒョンジュン / イ・ミンホ / チョン・ジョンミョン / チョン・ギョウン ほか vol.009 INFINITE / パク・・・シフ・シフ 2012/1/21 20846-3/3 \ 933 ピンナップ:両面ともINFINITE AFTERSCHOOL / 大国男児 / Girl's Day / Block.B / SHU-I / Apeace / パク・シフ / カン・ジファン / ANDY / ジヒョク / SE7EN / 2AM / U-KISS / 小田切ジョー&チャン・ドンゴン / GACKT vol.010 イ・・・スンギ・スンギ / イイイ・イ・・・ミンホミンホ 2012/2/2 20846-4/5 \ 933 パク・ミニョン / ク・ハラ / Jphn-Hoon / 2AM / AFTERSCHOOL / Secret / JAY PARK / ALEX / SM☆SH / N-TRAIN / N-sonic / SHU-I / Apeace / チョ・ヒョンジェ / チョン・イル / イ・ジャンウ / チャン・ナラ 他 vol.011 U-KISS / IU 2012/3/22 20846-5/5 \ 933 ピンナップ: U-KISS / IU T-ARA / John-Hoon / ZE:A / 大国男児 / SHU-I / Apeace / イ・ジュンギ / チェ・シウォン / チョン・ジヌン / チソン / キム・ ヒョンジュン / チャ・スンウォン / コン・ヒョジン / ハ・ジウォン ほか vol.012 イ・・・ジュンギ・ジュンギ / INFINITE 2012/5/22 20846-7/5 \ 933 ピンナップ:イ・ジュンギ / INFINITE INFINITE / SE7VEN / 2AM / T-ARA / 大国男児 / ジヨン&ゴニル / イ・ジヌク / ベ・スビン / BIGBANG / Nana / SHU-I /