The Appearance and Evolution of the Disaster Joke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORANGE COUNTY CAUFORNIA Continued on Page 53

KENNEDY KLUES Research Bulletin VOLUME II NUMBER 2 & 3 · November 1976 & February 1977 Published by:. Mrs • Betty L. Pennington 6059 Emery Street Riverside, California 92509 i . SUBSCRIPTION RATE: $6. oo per year (4 issues) Yearly Index Inc~uded $1. 75 Sample copy or back issues. All subscriptions begin with current issue. · $7. 50 per year (4 issues) outside Continental · · United States . Published: · August - November - Febr:UarY . - May .· QUERIES: FREE to subscribers, no restrictions as· ·to length or number. Non subscribers may send queries at the rate of 10¢ pe~)ine, .. excluding name and address. EDITORIAL POLICY: -The E.ditor does· not assume.. a~y responsibility ~or error .. of fact bR opinion expressed by the. contributors. It is our desire . and intent to publish only reliable genealogical sour~e material which relate to the name of KENNEDY, including var.iants! KENEDY, KENNADY I KENNEDAY·, KENNADAY I CANADA, .CANADAY' · CANADY,· CANNADA and any other variants of the surname. WHEN YOU MOVE: Let me know your new address as soon as possibie. Due. to high postal rates, THIS IS A MUST I KENNEDY KLyES returned to me, will not be forwarded until a 50¢ service charge has been paid, . coi~ or stamps. BOOK REVIEWS: Any biographical, genealogical or historical book or quarterly (need not be KENNEDY material) DONATED to KENNEDY KLUES will be reviewed in the surname· bulletins·, FISHER FACTS, KE NNEDY KLUES and SMITH SAGAS • . Such donations should be marked SAMfLE REVIEW COPY. This is a form of free 'advertising for the authors/ compilers of such ' publications~ . CONTRIBUTIONS:· Anyone who has material on any KE NNEDY anywhere, anytime, is invited to contribute the material to our putilication. -

We Are All Called to Be Doormen Faith 3

NowadaysMontgomery Catholic Preparatory School Fall 2015 • Vol 4 • Issue 1 Administration 2 We are All Called to be Doormen Faith 3 Perhaps Saint André Bessette countless achievements of the School News 6 should be named the Patron saint students of Montgomery Catholic Student Achievement 9 for this issue of Nowadays. Preparatory School in many areas: academic, the arts, athletics, and Alumni 14 St. André was orphaned at a service. These accomplishments very early age, lived a life of Faculty News 17 are due to the students’ extreme poverty, and had little dedication and hard work, but Memorials 18 opportunity to go to school. also to their parents’ support and He would be termed illiterate Advancement 20 teacher involvement. They are in today’s standards because the doormen helping to open the he was barely able to write his doors of possibilities. name. He was short in stature and struggled with health issues. You will also read about the many Planning process has been on However, this did not deter him donors that have supported going for the past 10 months, and from his desire to become a MCPS through their gifts of time, on June 18 over 100 stakeholders, member of the Congregation of talent, and treasure. Through including our local priests, parents, the Holy Cross. their generosity many wonderful and invited guests, came together things are happening at each of to hammer out a plan that would After three years of being our campuses. We are so grateful map out MCPS’s course. These a novitiate, he was denied to Partners in Catholic Education, people are the doormen for our admittance. -

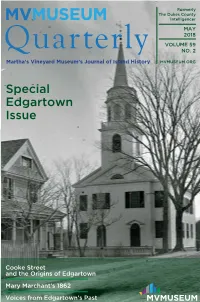

Special Edgartown Issue

59 School Street Box 1310 Edgartown MA 02539 Formerly MVMUSEUM The Dukes County Intelligencer MAY 2018 VOLUME 59 Quarterly NO. 2 Martha’s Vineyard Museum’s Journal of Island History MVMUSEUM.ORG Special Cooke Street Edgartown Landmarks Issue (l to r) Cooke Street landmarks: Commercial Wharf, the Old Mayhew Homestead, the Thomas Cooke House, and the Rev. Joseph Thaxter House. The Mayhew and Thaxter houses have been demolished; the Cooke House, owned by the Museum, is open to the public in the summer. Cooke Street and the Origins of Edgartown Mary Marchant’s 1862 Voices from Edgartown’s Past MVMUSEUM.ORG MVMUSEUM Cover, Vol. 59 No. 2.indd 1 7/3/18 5:10:20 PM Membership Dues Student ..........................................$25 Individual .....................................$55 (Does not include spouse) Family............................................$75 Sustaining ...................................$125 Patron ..........................................$250 Benefactor...................................$500 President’s Circle .....................$1,000 Memberships are tax deductible. For more information on membership levels and benefits, please visit www.mvmuseum.org Edgartown The Martha’s Vineyard Museum and its journal were both founded—un- der other names—in Edgartown: one in 1922, the other in 1959. This issue of the MVM Quarterly is a celebration of the town that gave them birth. Tom Dunlop’s lead article, “Edgartown Rising,” uses Cooke Street as a window on the interplay of tensions between religion and commerce— and the sometimes violent struggles between rival sects—that shaped the town’s growth. A pair of articles by Elizabeth Trotter dive deep into Edgartown during the tumultuous 1860s, through the private diary of 24-year-old Mary Marchant and the very public editorials in which James Cooms, the fiery young editor of the Gazette, called for eradication of slav- ery and equal rights for African Americans. -

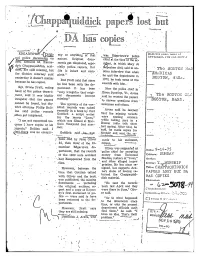

Chappaquiddick

2/15/2019 Chappaquiddick what-when-how In Depth Tutorials and Information Chappaquiddick On the night of 18 July 1969, Mary Jo Kopechne died when the car in which she was riding plunged off a low bridge on the Massachusetts island of Chappaquiddick and landed on its roof in the water below. Senator Edward M. Kennedy reported to local police the following morning that he had been driving the car at the time of the accident. Charged with leaving the scene of an accident, he pleaded guilty and was given a suspended sentence. A coroner’s inquest into Kopechne’s death held in January 1970 and a subsequent grand jury investigation held in March of that year produced no new legal developments. The last official result of the case was the revocation of Kennedy’s driver’s license in May 1970 after a routine fatal-accident investigation by the Registry of Motor Vehicles. The hearing examiner, like the judge who had sentenced Kennedy, concluded that he had been driving too fast. Kennedy made no public statement until the week following the accident, when he spoke in a live television broadcast from his home. He stated in that broadcast, and has maintained ever since, that he was driving (but not intoxicated) on the night of the accident and that after the car went into the water he made vigorous (but unsuccessful) efforts to rescue Kopechne. All conspiracy theories about the accident reject this version of events. The theories fall into three groups that allege, respectively, a conspiracy to place blame on Kennedy, a conspiracy to divert blame from Kennedy, and a conspiracy to cover up an earlier crime by staging the “accident.” The Setting and the Accident The island of Martha’s Vineyard lies seven miles off the southeastern coast of Massachusetts. -

Corda Al Coilo Per Ripescare Mary Jo Abruzzese

I'Unit a t ""bote 20 settembrt 1969 PAG. 7 / ectil e notlzie Marito e moglie sottrassero due vasetti di omogeneizzati in un grande magazzino Un articolo dell© « Civiltd Cottolica » DA QUATTRO MESI IN CARCERE PER 250 LIRE / GESUITI AvtviM i casa *• M«fct nttJatt dia avava bistgio di cika — Sorprasi a arrastati sane stoH riaiaaaatt par diratttohaa — Faria ptari**agravata — Ora, dapa 125 (iarai, II gMiea MraHara iaaWtaa cha la casl 4al gaaara aaa aiUtaaa la circattaaza *sggravajrti — Daciaa la scarcaraziaaa, mm sala par Ihrnaa INVITAN0 P.\LERMO. 19 Sono in carcere dal 14 maggio scorso. quasi quattro mesi. 125 giorni per l'esattezza. per aver sottratto due vasetti di DEFREGGER came omoge-neizzata in un grande magazzino per un valore A nove mesi imprigionato con la madre di circa 250 lire. Si tratta di Giuseppe Lo Pinto, un padre di famiglia disoc cupato di Palermo, e di sua moglie Rosaria Vasta. II 14 mag gio. appunto, entrarono alia «Standa > per comprare alcuni oggetti. Uno dei loro bambini era a casa ammalato: quando A DMETIERSl la donna \ide ben allineati sullo scaffale una fila di vasetti di carne omogeneizzata, penso al bambino che aveva bisogno « E' chiaro che la strage di Filetto fu un delitto Chi condann6 di cibo leggero e nutriente e non seppe resistere alia tenta- zione: innlo due barattoli nella borsetta per portarseli a casa. esecrando* — Rivelazioni del «Me$$aggero» Ma le ando male: la sorvegliante l'aveva vista, e la con- segno. insieme al marito. alia polizia. come una volgare del in- La Civilta Cattoliea invita. -

Edward Kennedy

AAmmeerriiccaannRRhheettoorriicc..ccoomm Edward Kennedy Chappaquiddick Address to the People of Massachusetts Broadcast 29 July 1969 AUTHENTICITY CERTIFIED: Text version below transcribed directly from audio My fellow citizens: I have requested this opportunity to talk to the people of Massachusetts about the tragedy which happened last Friday evening. This morning I entered a plea of guilty to the charge of leaving the scene of an accident. Prior to my appearance in court it would have been [im]proper for me to comment on these matters. But tonight I am free to tell you what happened and to say what it means to me. On the weekend of July 18th, I was on Martha's Vineyard Island participating with my nephew, Joe Kennedy -- as for thirty years my family has participated -- in the annual Edgartown Sailing Regatta. Only reasons of health prevented my wife from accompanying me. On Chappaquiddick Island, off Martha's Vineyard, I attended, on Friday evening, July 18th, a cook-out I had encouraged and helped sponsor for a devoted group of Kennedy campaign secretaries. When I left the party, around 11:15pm, I was accompanied by one of these girls, Miss Mary Jo Kopechne. Mary Jo was one of the most devoted members of the staff of Senator Robert Kennedy. She worked for him for four years and was broken up over his death. For this reason, and because she was such a gentle, kind, and idealistic person, all of us tried to help her feel that she still had a home with the Kennedy family. Transcription updated 2018 by Michael E. -

Dr. Bruce Gee/Hoed

CHAPPAQUIDDICK: WHERE TED KENNEDY WRECKED HIS CHANCES OF BECOMING PRESIDENT An Honors Thesis (HONR 400) By Abby Busse Thesis Advisor Dr. Bruce Gee/hoed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 29,2018 Expected Date of Graduation May2018 1 Abstract This thesis examines the impact of Edward Kennedy's wreck at Chappaquiddick on the rest of his political career. This wreck proved td be extremely controversial, as Kennedy could not provide a coherent story as to how the wreck occurred or why Mary Jo Kopechne was in the car with him and not rescued as the car sank into the water. By examining Chappaquiddick's impact on Kennedy's presidential hopes, I consider the importance of perceived morality in a presidential candidate. This paper includes the presidential elections from 1968 to 1980, including an examination of Chappaquiddick's impact on Watergate. Information has been found in primary and secondary sources, including books, newspapers, memoirs, and Internet archives. This paper argues that even the most popular political figures are not above moral reproach from the American public. Edward Kennedy's wreck at Chappaquiddick was the true end of Camelot and ruined any chance that he had of following in his brother's footsteps as President of the United States. Acknowledgments I wish to thank Dr. Bruce Geelhoed, my professor and supervisor through this process, for his patience and guidance through the thesis process and for pushing me to expand my paper and make it better. I am also grateful to my family and friends who encouraged me to continue writing when the process seemed difficult. -

Recent Cases

Volume 74 Issue 3 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 74, 1969-1970 3-1-1970 Recent Cases Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Recent Cases, 74 DICK. L. REV. 514 (1970). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol74/iss3/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recent Cases NEGLIGENCE-THE END OF THE IMPACT RULE IN PENNSYLVANIA Niederman v. Brodsky, 436 Pa. 401, 261 A.2d 84 (1970). The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania recently abolished what is commonly referred to as the impact rule. In a complete reversal of existing precedent, the court, in Niederman v. Brodsky' held that physical impact was no longer a prerequisite to recovery where the plaintiff sustains injury solely from a fear of being struck. This decision overruled Bosley v. Andrews 2 and cast doubt on the present validity of Knaub v. Gotwalt.3 The plaintiff, Harry Niederman, alleged he was standing with his son on a sidewalk in Philadelphia. The defendant's negligently operated car skidded onto the sidewalk striking the boy, a pole, a fire hydrant and a newsstand. The plaintiff claimed that he almost immediately sustained a heart attack which resulted in a five week hospital confinement. 4 Since no impact was alleged, the lower court sustained the defendant's preliminary objections and reluc- 1. -

Senator Edward "Ted" Kennedy Part 16 of 27

" s M __ __ ....-- -r---~- .-. , ....-- . ii; erehitiieleiiels he -1? '>---4,,____ " i * ~;h.s;.hes* _ 0¢ 1 |.,,____ q--»-as-..u _ 1 ¢;.--J----n_ » - F EDGARTOW -Qpi-' '-Win??- nal police documents on acy or anything of that 4 Sen. Edward M. Kenne- nature. Original docu- dys Chappaquiddick acci- ments get misplaced, espe- =__v_t[§_§___bEdgartou'ns' police t <1m,'.-ne still missing, but cially police reponts, Our chief at the tin1e6TthF§,c- the district attorney said file is intact and com-'cident, in which Mary Jo yesterday it doesnt matter plete. _ " " - IQpeChl'18 died, said in an- because he has copies. But Pratt said that since other interview that when he has been with the de- _ he quit*the department in Sgt. Bruce Pratt, acting partment it has been 1973,he took some of the head of the police depart- very irregular that origi- records with him.. i ment, said it was highly nal documents become - Now the police chief in 1, ,_,_.,_.._.,_-.__..- -..-_-.-_-._...__.-- _.-... irregular -that the papers missing. .Essex J unctio_n, Vt., Arena I ln.dl'-n92a;vu |n_numr c-i cannot be found, but-dis- The mystery of the van- [said he wanted the papers ii cm:-poprar, rtty unn nl<192t~l trict attorney Philip Roll- ished records was raised to answer questions from ;¬92e,§1__the1§ ins said was police no ' conspir-records recently in a book by. Carl newsmen andiothers. V often get misplaced. -

Page from the Past June 27,1940 80 Years Ago

B8 - Lamesa Press-Reporter www.pressreporter.com Sunday, June 28, 2020 Raymond Vargas,. Owner Page from the Past June 27,1940 80 years ago Moments in time G SCREEN #1 On July 14, 1798, Congress passes the Sedition Act. Th e act permitted the prosecution of individuals who voiced or printed what the government deemed to be malicious re- marks about the president or the U.S. government. On July 19, 1879, Doc Holliday commits his fi rst murder, killing a man for shooting up his saloon. Despite his repu- tation as a deadly gunslinger, Doc Holliday engaged in just eight shootouts during his life, and killed only two men. On July 17, 1920, Nils Bohlin, the Swedish engineer and inventor responsible for the three-point lap and shoulder seatbelt, is born. Before 1959, only two-point lap belts were available in automobiles. On July 18, 1969, aft er leaving a party on Chappaquiddick Island, Sen. Edward "Ted" Kennedy of Massachusetts drives an Oldsmobile off a bridge into a tide-swept pond. Kennedy Friday 7 p.m. escaped the submerged car, but his passenger, 28-year-old Saturday 2, 7 p.m. Mary Jo Kopechne, did not. Th e senator did not report the Sunday 2, 7 p.m. fatal car accident for 10 hours. On July 13, 1985, at Wembley Stadium in London, Prince Tues, Wed, Thurs 7:00 p.m. Charles and Princess Diana offi cially open Live Aid, a world- SCREEN #2 wide rock concert organized to raise money for the relief of famine-stricken Africans. Th e 16-hour "superconcert" was globally linked by satellite to more than a billion viewers in 110 nations. -

Edmund G. "Ted" Miller Papers, 1926-1971

99 Main Street, Haverhill, MA 01830 978-373-1586 ext. 642 http://www.haverhillpl.org/information-services/local-history-2/ Edmund G. "Ted" Miller Papers, 1926-1971 Collection Summary Reference Code: MRQ, US. Repository: Special Collections, Haverhill Public Library, Haverhill, Massachusetts. Call Number: MSS 8 Creator: Miller, Edmund G., 1918-2008 Title: Edmund G. “Ted” Miller Papers, 1926-1971 Dates: 1926-1971 Size: 1.417 linear feet (2 boxes) Language(s): Collection materials are in English. Abstract: Edmund “Ted” Miller was a cartoonist, artist, and weatherman. He created a comic strip called “The Diary of Snubs Our Dog" for the Christian Science Monitor. Later he would become a weatherman for WHDH-TV & WCVB-TV for twenty-two years. Biographical Sketch Edmund "Ted" Miller was born in Haverhill, Massachusetts, on 19 February 1918. His father was Ralph G. Miller and his mother was Hellen A. (Sargent) Miller. Ted had two siblings Julian S. Miller, and his twin sister Janice de Moulpied. He attended school in Haverhill and graduated from Haverhill High School in 1935. During World War II he served four years in the U.S. Army Air Corps as an intelligence specialist before his discharge as a Master Sergeant in 1945. Around this time his cartoons first started to appear. The earliest ones appeared in the Army publication, Stars and Stripes. Miller married Elizabeth P. "Betty" (Peel) Miller (1918-2009). Betty and Ted had been members of The North Church Players in Haverhill. The two of them moved from Long Island, New York, to 224 Main Street, West Newbury, Massachusetts in 1946. -

Nixon Urges U.N. Pressure on North Vietna M

MOUND TIDES WATER CONDITION HIGH LOW CHARLIE III 9:47 a.m. 4:52 a.m.ASHORE 11:17 p.m. 4:04 p.m. U.S. NAVAL BASE, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA 11.0 MILLION GALLONS Phone 9-5247 Date FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 1969 Radio (1340) TV (Ch. 8) Nixon Urges U.N. Pressure on North Vietna M UNITED NATIONS (AP/AFRTS)-- President Nixon today urged--"in the name of peace"--that the Army to Court-Martial 6 Officers United Nations General Assembly put diplomatic 0 pressure on North Vietnam to work for peace in In Alleged Murder of Vietnamese the Paris talks. Mr. Nixon in his first presidential address SAIGON (AP/AFRTS)-- The Army has ended a two- to the United Nations assembly urged that mem- month investigation into the alleged murder of ber nations whohave taken an active interest a Vietnamese national and will court martial in peace in Vietnam should--"take an active six of the eight Green Berets held in the case. hand in achieving it." He said if member na- The formal charges are murder and conspiracy tions were successful, "the-war could end." to commit murder, but the Pentagon says the Mr. Nixon blamed Hanoi for its refusal to cases will be treated as "non- negotiate in Paris on terms capital," which apparently Dini Files New Petition other than those which would rules out the death penalty. pre-determine the result of a All of the Green Berets who For Kopechne Autopsy settlement. will be court martialed are NEW BEDFORD, Mass.(AP/AFRTS) He said such terms would officers, including Col.