Institute for Advanced Study in Vocational-Technical Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wrestling Boys Varsity Western 2008

2008 OIA - WESTERN DIVISION VARSITY BOYS WRESTLING CHAMPIONSHIPS INDIVIDUAL RESULTS 103 Lbs 112 Lbs 1st Shane Pantastico-Banaay - Campbell High School 1st Thomas Perez - Radford High School 2nd 2nd Justin Garcia - Leilehua High School 3rd 3rd Richard Nazareno - Pearl City High School 4th 4th Adam Shimizu - Campbell High School 5th 5th Kaleo Hew-Len - Kapolei High School 6th 6th 119 Lbs 125 Lbs 1st Bill Takeuchi - Pearl City High School 1st Jack Oliveros - Aiea High School 2nd Dallas Collier - Aiea High School 2nd Hailey Barnes - Kapolei High School 3rd Mathias Yacapin - Leilehua High School 3rd Braxton Delos Santos - Pearl City High School 4th Ralph Custodio - Kapolei High School 4th Rayn Celestino - Mililani High School 5th Mason Sur Kessler - Waianae High School 5th Marc Davis - Campbell High School 6th John Dinh - Waipahu High School 6th Jayson Dumaoal - Leilehua High School 130 Lbs 135 Lbs 1st Lance Villatora - Leilehua High School 1st Chad Diamond - Mililani High School 2nd Toran Kobayashi - Waialua High School 2nd Arnold Berdon - Waianae High School 3rd Jason Wong - Pearl City High School 3rd Stefan Kobayashi - Pearl City High School 4th Ronald Grieg - Kapolei High School 4th Adrian Foster - Waialua High School 5th Cory Freitas - Campbell High School 5th Harvey Karas - Aiea High School 6th Shiloh Aiu - Mililani High School 6th Thomas Graham - Leilehua High School 140 Lbs 145 Lbs 1st Ray Mathewson - Waianae High School 1st Anthony Rivera - Leilehua High School 2nd Matthew Higa - Aiea High School 2nd Boston Salmon - Waianae High School -

June 2020 Volume 37 · Number 6 · Richard Bettini, President & Chief Executive Officer · Dr

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 37 · NUMBER 6 · RICHARD BETTINI, PRESIDENT & CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER · DR. STEPHEN BRADLEY, CHIEF MEDICAL OFFICER · DAN GOMES, BOARD CHAIR Health Center Celebrates its Medical School’s 10th Graduating Class On Thursday, May 21st, 4 new doctors from the Wai‘anae campus of the A. T. Still University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona (ATSU-SOMA) graduated in a virtual ceremony along with their fellow classmates. All 4 graduates have chosen to pursue primary care fields. Two of our 4 graduates will remain in Hawai‘i as part of the University of Hawaii’s Family Medicine residency program. WCCHC became part of this exciting new medical education program in 2007 when ATSU-SOMA selected the Health Center as one of only 11 “Hub Sites” located at community health centers across the country. After spending their first year at the Arizona campus, medical students spend their second, third and Final year studying and training with health center doctors and staff while taking care of members of the community who they will hopefully serve again in the future once they complete their residency. Since 2011, seventy have graduated from Congratulations to (L to R) Dr. Elizabeth Denisova, Dr. Manpreet Sidhu, Dr. Gladys Devano and Dr. Kapono Chang the Waianae Campus of ATSU-SOMA with 80% choosing primary care for their residency. The Health Center congratulates our latest graduating class and is proud of their choices for residency: • Dr. Elizabeth Denisova: Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency at Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center in West Islip, New York • Dr. Manpreet Sidhu: Internal Medicine Residency at Las Palmas del Sol Healthcare in El Paso, Texas • Dr. -

School Colors

SCHOOL COLORS Name Colors School Colors OAHU HIGH SCHOOLS & COLLEGES/UNIVERSITIES BIG ISLAND HIGH SCHOOLS Aiea High School green, white Christian Liberty Academy navy blue, orange American Renaissance Academy red, black, white, gold Connections PCS black, silver, white Anuenue High School teal, blue Hawaii Academy of Arts & Science PCS silver, blue Assets High School blue, white, red Hawaii Preparatory Academy red, white Campbell High School black, orange, white Hilo High School blue, gold Castle High School maroon, white, gold Honokaa High School green, gold Calvary Chapel Christian School maroon, gold Kamehameha School - Hawaii blue, white Christian Academy royal blue, white Kanu O Kaaina NCPCS red, yellow Damien Memorial School purple, gold Kau High School maroon, white Farrington High School maroon, white Ke Ana Laahana PCS no set colors Friendship Christian Schools green, silver Ke Kula O Ehukuikaimalino red, yellow Hakipuu Learning Center PCS black, gold Keaau High School navy, red Halau Ku Mana PCS red, gold, green Kealakehe High School blue, silver, gray Hanalani Schools purple, gold Kohala High School black, gold Hawaii Baptist Academy gold, black, white Konawaena High School green, white Hawaii Center for the Deaf & Blind emerald green, white Kua O Ka La NCPCS red, yellow, black Hawaii Technology Academy green, black, white Laupahoehoe Community PCS royal blue, gold Hawaiian Mission Academy blue, white Makua Lani Christian Academy purple, white Hoala School maroon, white Pahoa High School green, white Honolulu Waldorf School -

Honolulu Marathon HHSAA Hawaii State Cross Country Championships October 27, 2018

Honolulu Marathon HHSAA Hawaii State Cross Country Championships October 27, 2018 Place TmPl No. Name Yr School Varsity Boys ===== ==== ==== ================== == ========================= ======== 1 1 22 ADAM HARDER 11 Hanalani 16:50.85 2 2 135 HUNTER SHIELDS 10 Maui High 16:59.36 3 3 132 ADAM HAKOLA 11 Maui High 17:09.08 4 4 133 DAMON WAKEFIELD 11 Maui High 17:14.97 5 5 3 CHARLES SAKAMAKI 12 Iolani 17:19.43 6 6 5 JOSHUA LERNER 10 Iolani 17:22.64 7 141 NARAYANA SCHNEIDER 11 McKinley High School 17:22.79 8 186 AZIAH SCHAAL 12 St. Louis 17:29.43 9 7 95 KANE CASILLAS 12 Kauai High School 17:33.75 10 8 167 PARKER MOONEY 12 Punahou 17:35.69 11 9 163 KAINALU PAGENTE 10 Pearl City High School 17:39.94 12 10 65 SEAN GUILLERMO 12 Kalani High School 17:43.62 13 11 169 CAMERON COFFELT 10 Punahou 17:46.53 14 12 188 ERIC CABAIS-FERNAN 12 Waiakea 17:48.05 15 13 183 COLE DAVIDSON 10 Seabury Hall 17:48.64 16 142 KOBY SHUMAN 11 McKinley High School 17:51.05 17 14 105 ALEC ANKRUM 10 Kealakehe 17:52.41 18 177 REIMON WADA 12 Roosevelt High School 17:54.36 19 15 24 BENJAMIN HODGE 10 Hanalani 17:54.45 20 92 GARRETT SMITH 12 Kapaa High School 17:58.51 21 16 53 MATTHEW VICKERS 12 Island School 17:58.66 22 17 14 LOGAN FINLEY 10 Campbell High School 18:03.36 23 195 CHAI CAPILI 11 Waialua High School 18:05.26 24 18 134 CONNOR KONG 10 Maui High 18:06.30 25 19 6 MICHAEL SHIINOKI 10 Iolani 18:07.26 26 20 30 CHRISTIAN KUWAYE 10 Hawaii Baptist Academy 18:14.15 27 21 150 LUIS GARCIA 10 Mililani High School 18:15.67 28 22 151 KALE GLUNT 10 Mililani High School 18:15.76 -

Boys Varsity West Results 2019

2019 OIA WEST VARSITY BOYS WRESTLING CHAMPIONSHIPS INDIVIDUAL RESULTS 106 Lbs 113 Lbs 1st Nicholas Cordeiro - Waianae High School (FALL ) 1st Dylan Ramos - Leilehua High School (FALL ) 2nd Isaiah Siaris - Mililani High School 2nd Kinau Mcbrayer - Kapolei High School 3rd Khansith Chanthabouasith - Leilehua High School (FALL ) 3rd Dylan Cuesta - Mililani High School (D: 6-2) 4th Bronson Maele - Campbell High School 4th Micah Ongies-Vellalos - Pearl City High School 5th 5th Kenji Carino - Aiea High School (DEF) 6th 6th Andrew Bushong - Waianae High School 7th 7th 8th 8th 120 Lbs 126 Lbs 1st Josiah Tamasaka - Pearl City High School (FALL ) 1st Weiyi Zheng - Aiea High School (MD: 14-2) 2nd Peter Natividad - Leilehua High School 2nd James Lum - Pearl City High School 3rd Kainoa Sumailo - Campbell High School (D: 8-12) 3rd Prestiege Kahookele-Himalaya - Nanakuli High School (D: 3-0) 4th Kenichi Price - Waipahu High School 4th Joshua Paz - Campbell High School 5th Atalbert Debrum - Kapolei High School () 5th Colby Ilae - Waianae High School (D: 2-1) 6th 6th Ashton Manibusan - Radford High School 7th 7th Zackree Inis - Waipahu High School (TF: 16-0) 8th 8th Akaia-Koni Mcintosh - Waialua High School 132 Lbs 138 Lbs 1st Dante Bareng - Aiea High School () 1st Kaena Desantos - Leilehua High School (FALL ) 2nd Brock Gooman - Campbell High School 2nd Elijah Diamond - Mililani High School 3rd Logan Leialoha - Radford High School (D: 3-1) 3rd Jayven Lomavita - Pearl City High School (D: 5-9) 4th Breeze Keolanui - Waianae High School 4th Daniel Branigan -

Immunization Exemptions School Year 2018‐2019

Immunization Exemptions School Year 2018‐2019 HAWAII COUNTY School Religious Medical School Name Type Island Enrollment Exemptions Exemptions CHIEFESS KAPIOLANI SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 363 0.28% 0.00% CHRISTIAN LIBERTY ACADEMY 9‐12 PRIVATE HAWAII 46 2.17% 0.00% CHRISTIAN LIBERTY ACADEMY K‐8 PRIVATE HAWAII 136 0.00% 0.00% CONNECTIONS: NEW CENTURY PCS CHARTER HAWAII 349 14.04% 0.29% E.B. DE SILVA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 455 3.96% 0.00% HAAHEO ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 196 9.18% 0.00% HAILI CHRISTIAN SCHOOL PRIVATE HAWAII 117 4.27% 4.27% HAWAII ACADEMY OF ARTS & SCIENCE: PCS CHARTER HAWAII 672 2.38% 0.00% HAWAII MONTESSORI SCHOOL ‐ KONA CAMPUS PRIVATE HAWAII 7 0.00% 0.00% HAWAII PREPARATORY ACADEMY PRIVATE HAWAII 620 7.90% 0.00% HILO HIGH SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 1170 2.65% 0.17% HILO INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 563 2.31% 0.00% HILO UNION ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 425 0.94% 0.00% HOLUALOA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 536 10.82% 0.37% HONAUNAU ELEMENTARY PUBLIC HAWAII 133 5.26% 0.00% HONOKAA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 404 3.71% 0.00% HONOKAA INTER &HIGH SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 615 2.11% 0.16% HOOKENA ELEMENTARY & INTER. PUBLIC HAWAII 110 4.55% 0.00% INNOVATIONS: PUBLIC CHARTER SCHOOL CHARTER HAWAII 237 16.88% 0.00% KA UMEKE KA EO: PCS CHARTER HAWAII 215 5.58% 0.00% KAHAKAI ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 750 5.87% 0.13% KALANIANAOLE ELEM. & INTER. SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 307 2.28% 0.00% KAMEHAMEHA SCHOOLS ‐ HAWAII CAMPUS (9‐12) PRIVATE HAWAII 575 1.39% 0.00% KAMEHAMEHA SCHOOLS ‐ HAWAII CAMPUS (K‐8) PRIVATE HAWAII 580 1.72% 0.00% KANU O KA AINA SCHOOL: PCS CHARTER HAWAII 598 1.67% 0.00% KAU HIGH & PAHALA ELEM. -

Accreditation Status of Hawaii Public Schools

WASC 0818 Hawaii update Complex Area Complex School Name SiteCity Status Category Type Grades Enroll NextActionYear-Type Next Self-study TermExpires Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Radford Complex Admiral Arthur W. Radford High School Honolulu Accredited Public School Comprehensive 9–12 1330 2020 - 3y Progress Rpt 2023 - 11th Self-study 2023 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Radford Complex Admiral Chester W. Nimitz School Honolulu Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 689 2019 - Mid-cycle 1-day 2022 - 2nd Self-study 2022 Windward District-Castle-Kahuku Complex Castle Complex Ahuimanu Elementary School Kaneohe Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 301 2020 - Mid-cycle 1-day 2023 - 2nd Self-study 2023 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Aiea Complex Aiea Elementary School Aiea Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 375 2020 - Mid-cycle 2-day 2023 - 2nd Self-study 2023 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Aiea Complex Aiea High School Aiea Accredited Public School Comprehensive 9–12 1002 2019 - 10th Self-study 2019 - 10th Self-study 2019 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Aiea Complex Aiea Intermediate School Aiea Accredited Public School Comprehensive 7–8 607 2020 - 8th Self-study 2020 - 8th Self-study 2020 Windward District-Kailua-Kalaheo Complex Kalaheo Complex Aikahi Elementary School Kailua Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 487 2021 - Mid-cycle 1-day 2024 - 2nd Self-study 2024 Honolulu District-Farrington-Kaiser-Kalani Complex -

School: Teacher: Career Pathway

Student/Teacher Name: School: Teacher: Career Pathway: Career Pathway Program of Study Event/Placement: Paul Balico James Campbell High School Jan Takamatsu Arts and Communication Highest Proficiency Digital Media Sydney Laciste James Campbell High School Arts and Communication Highest Proficiency Digital Media Nathan Guerrero Waianae High School Michael O'Connor Arts and Communication 2ndHighest Proficiency Digital Media Aimee Nitta Waianae High School Arts and Communication 2nd Highest Proficiency Digital Media Haeley Ikeda Kalaheo High School Kathy Shigemura Arts and Communication 3rd Highest Proficiency Digital Media Ashley Stanfovitz Kalaheo High School Arts and Communication 3rd Highest Proficiency Digital Media Serina Kerbaugh Waianae High School Michael O'Connor Arts and Communication Highest Proficiency Graphic Design Technology I Elmarie Manuel Waianae High School Arts and Communication Highest Proficiency Graphic Design Technology I Quinton Potter King Kekaulike High School Ryan Arakawa Arts and Communication 2nd Highest Proficiency Graphic Design Technology I Jarid Rother King Kekaulike High School Arts and Communication 2nd Highest Proficiency Graphic Design Technology I Aimee Bowen James Campbell High School Jan Takamatsu Arts and Communication 3rd Highest Proficiency Graphic Design Technology I Kathyrine Cabalar James Campbell High School Arts and Communication 3rd Highest Proficiency Graphic Design Technology I Bill Ben James Campbell High School Jan Takamatsu Arts and Communication Highest Proficiency Animation Andrew -

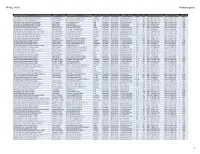

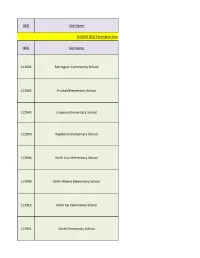

HIDOE 470 Applications FY2017.Xlsx

BEN Site Name HAWAII DOE Farrington Kaiser Kalani 470 FY 2017 Voice Services BEN Site Name 112944 Farrington Community School 112942 PuuhaleElementary School 112945 Linapuni Elementary School 112900 Kapalama Elementary School 112946 Kalihi Uka Elementary School 112949 Kalihi Waena Elementary School 112913 Kalihi Kai Elementary School 112941 Kalihi Elementary School 112940 Kaewai Elementary School 112936 Fern Elementary School 112939 Dole Middle School 112911 Farrington High School 112947 Kalakaua Middle School 112982 Kaiser High School 112958 Niu Valley Middle School 112955 Ainahina Elementary School 112980 Haihaione Elementary School 112981 Kamiloiki Elementary School 112984 Kokohead Elementary School 112953 Kalani High School 112879 Kaimuki Middle School 112886 Kahala Elementary School 112864 Liholiho Elementary School 112856 Waikiki Elementary School 112887 Wilson Elementary School 112855 Hawaii School for the Deaf & Blind HAWAII DOE Kauai 470 FY 2017 Voice Services BEN Site Name 112571 Hanalei Elementary School 112678 Kapaa Elementary School 112676 Kapaa Middle School 112675 Kapaa High School 112723 Kaumualii Elementary School 112721 Wilcox Elementary School 209291 Kamakahelei Msiddle School 112724 Kauai High School 112704 Koloa Elementary School 112699 Kilauea Elementary School 112718 KAUAI Community School 112651 Kalaheo Elementary School 112546 Eleele Elementary School 112824 Waimea Canyon Msiddle School 112822 Waimea High School 112694 Kekaha Elementary School HAWAII DOE Kailua - Kalaheo 470 FY 2017 Voice Services BEN Site Name -

VT 017 190 NOTE Education Programs for the Disadvantaged, CO Training Program

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 068 689 VT 017 190 TITLE Occupational Resource Manual for Hawaii. INSTITUTION Hawaii Univ., Honolulu. NOTE 787p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$26.32 DESCRIPTORS Bibliographies; Community Role; Disadvantaged Groups; *Employment Opportunities; Employment Services; Employment Trends; Humanities; Indexes (Locaters); Job Placement; Job Training; *Occupational Clusters; *Occupational Information; *Resource Guides; State Programs; Vocational Development; *Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS Dictionary of Occupational Titles; *Hawaii ABSTRACT Developed cooperatively between the Occupational Informations and Guidance Services Center under the Community College System and the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Hawaii, this occupational resource manual for Hawaii, bound in a 3-ring notebook, contains pertinent information for students, parents, counselors, and teachers on career opportunities, vocational education programs, job requirements, and job placement. For each of 15 occupational clusters, national and local employment opportunities, a general description, training and educational programs, and extensive job summaries correlated with the Dictionary of Occupational Titles are presented. Other resource materials include:(1) general job information,(2) Hawaii State Employment Service, (3) programs for the disadvantaged, CO training program opportunities, (5) a discussion of the future as it may affect individual career plans,(6) acknowledgments to community leaders, and (7) a brief reference list..A bibliography, general index, and an index of programs for the disadvantaged are included, as well as a detailed description of the manual's development and instructions for the user. Sub-indexes are included for the job areas, which emphasize career opportunities available for those with up to 2 years of post-secondary training. (AG) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. -

Manymany FACESFACES OFOF Meme

TheThe ManyMany FACESFACES OFOF MeMe the “happy” me the “mommy” me the “puzzled” me the “thinking” me the“Best” part of me! Blood Bank of Hawaii 2009 ANNUAL REPORT the “coach” me the “fun” me the “disagreeing” me the “surprised” me the“Best” part of me! Joe Lileikis SUPER DONOR Joe Lileikis’s calling came when he was 10 teacher, former All-American swimmer turned years old. His mother, a nurse and blood swim coach and Blood Bank of Hawaii Super donor recruitment coordinator in Southern Donor encourages his students to blend aca- California, often held gatherings for community demics with positive “life skills.” He is diplomatic leaders in her home. “My brothers and I when he says it, but his message is unvarnished: would help Mom set up a table with recruitment “I can’t force anyone to give the gift and donor information brochures,” recalls Joe of life, but I can provide them with the with characteristic enthusiasm. “That provided inspiration and opportunities to ‘take the foundation for my commitment to blood action and make it happen!’” donations, which began almost 20 year ago.” Today, the Niu Valley Intermediate School PRESIDENT & CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE Every day, people from all walks of life make the Blood Bank of Hawaii a part of their lives. Despite the many demands on their precious time, they donate blood so others’ lives may be saved or improved. Amid life’s complexities, their simple act of kindness means hope for Hawaii’s patients. “The Many Faces of Me,” the theme of this annual report, salutes our donors and supporters. -

Financial Aid Cover 15-16

Aloha Students and Families, What an exciting time this is for you! We know that this is also a very busy and challenging time, with critical deadlines to file applications for scholarships and financial aid, including the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). Bank of Hawaii Foundation is pleased to partner with the Pacific Financial Aid Association to sponsor the series of Financial Aid nights. We wish you all the best, as you pursue opportunities for higher education. Sincerely, Donna Tanoue President Bank of Hawaii Foundation PO Box 3170 Honolulu, HI 96802-3170 Tel 1-888-643-3888 boh.com THE NEXT COOL AND EXCITING CHAPTER OF YOUR LIFE. CONGRATULATIONS TO THE 2017 BANK OF HAWAII FOUNDATION SCHOLARS Adam Berg Richard Chen Konrad Cheng Michael Dressler Kehaulani Esteban Kelsey Floyd Pacific University University of University of Southern George Fox University University of Hawai‘i Leeward Community Exercise Science Pennsylvania California Biology at Hilo College Kapolei High School Biology Computer Science Kauai High School Hawaiian Studies Chemistry Roosevelt High School Maryknoll School Lanai High School Aiea High School Natalie Hajinelian Adriana Jones Abraham Kalavi Aubree Kim Christopher Skylah Kunihisa University of Hawai‘i Pacific University Grand Canyon Santa Clara Kobayashi Centralia College at Mānoa Sociology University University Pacific University Sociology Political Science Farrington High Business Economics Business Administration Business Administration Leilehua High School Sacred Hearts Academy School Kealakehe