United States V. Fullmer and the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act: "True Threats" to Advocacy Michael Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaggregating the Scare from the Greens

DISAGGREGATING THE SCARE FROM THE GREENS Lee Hall*† INTRODUCTION When the Vermont Law Review graciously asked me to contribute to this Symposium focusing on the tension between national security and fundamental values, specifically for a segment on ecological and animal- related activism as “the threat of unpopular ideas,” it seemed apt to ask a basic question about the title: Why should we come to think of reverence for life or serious concern for the Earth that sustains us as “unpopular ideas”? What we really appear to be saying is that the methods used, condoned, or promoted by certain people are unpopular. So before we proceed further, intimidation should be disaggregated from respect for the environment and its living inhabitants. Two recent and high-profile law-enforcement initiatives have viewed environmental and animal-advocacy groups as threats in the United States. These initiatives are the Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC) prosecution and Operation Backfire. The former prosecution targeted SHAC—a campaign to close one animal-testing firm—and referred also to the underground Animal Liberation Front (ALF).1 The latter prosecution *. Legal director of Friends of Animals, an international animal-rights organization founded in 1957. †. Lee Hall, who can be reached at [email protected], thanks Lydia Fiedler, the Vermont Law School, and Friends of Animals for making it possible to participate in the 2008 Symposium and prepare this Article for publication. 1. See Indictment at 14–16, United States v. Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty USA, Inc., No. 3:04-cr-00373-AET-2 (D.N.J. May 27, 2004), available at http://www.usdoj.gov/usao/nj/press/files/ pdffiles/shacind.pdf (last visited Apr. -

Animals Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 2

AAnniimmaallss LLiibbeerraattiioonn PPhhiilloossoopphhyy aanndd PPoolliiccyy JJoouurrnnaall VVoolluummee 55,, IIssssuuee 22 -- 22000077 Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 2 2007 Edited By: Steven Best, Chief Editor ____________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Lev Tolstoy and the Freedom to Choose One’s Own Path Andrea Rossing McDowell Pg. 2-28 Jewish Ethics and Nonhuman Animals Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 29-47 Deliberative Democracy, Direct Action, and Animal Advocacy Stephen D’Arcy Pg. 48-63 Should Anti-Vivisectionists Boycott Animal-Tested Medicines? Katherine Perlo Pg. 64-78 A Note on Pedagogy: Humane Education Making a Difference Piers Bierne and Meena Alagappan Pg. 79-94 BOOK REVIEWS _________________ Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal, by Eric Schlosser (2005) Reviewed by Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 95-101 Eternal Treblinka: Our Treatment of Animals and the Holocaust, by Charles Patterson (2002) Reviewed by Steven Best Pg. 102-118 The Longest Struggle: Animal Advocacy from Pythagoras to PETA, by Norm Phelps (2007) Reviewed by Steven Best Pg. 119-130 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume V, Issue 2, 2007 Lev Tolstoy and the Freedom to Choose One’s Own Path Andrea Rossing McDowell, PhD It is difficult to be sat on all day, every day, by some other creature, without forming an opinion about them. On the other hand, it is perfectly possible to sit all day every day, on top of another creature and not have the slightest thought about them whatsoever. -- Douglas Adams, Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency (1988) Committed to the idea that the lives of humans and animals are inextricably linked, Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (1828–1910) promoted—through literature, essays, and letters—the animal world as another venue in which to practice concern and kindness, consequently leading to more peaceful, consonant human relations. -

Inside Huntingdon Life Sciences

Inside Huntingdon Life Sciences A shocking report into what goes on behind the razor wire at Huntingdon Life Sciences written by two people who worked there in 2005 Huntingdon Life Sciences: A History of Abuse Huntingdon Life Sciences are no strangers to controversy. In 1989 they were first exposed by Sarah Kite working for the BUAV. She worked there for 6 months. This first undercover job saw international press coverage of Huntingdon LIfe Sciences for the first time. In 1997 Zoe Broughton worked undercover inside HLS in the UK for 9 weeks. She filmed, with a hidden camera, workers punching, shaking and terrifying 4 month old beagle pups. The resulting footage screened on national TV saw the suspension of Huntingdon’s licence. Also in 1997 and entirely separately, Michelle Rokke worked inside Huntingdon’s US lab in New Jersey. She filmed monkeys being cut open whilst they were still conscious, something reported here in 2005. In 2001 we received documents from inside Huntingdon’s lab in Occold, Suffolk. These showed that a worker was frequently on drugs and was dealing drugs on site. Another worker turned up drunk but was only disciplined for turning up late. Also in 2001 we recived a massive leak of documents relating to 5 years of experiments. These were xenotransplantation experiments on wild caught baboons for the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis. Hunting- don were frequently criticised by Novartis for sloppy procedures and they broke GLP (Good Laboratory Practice) 520 times during the course of these experiments. “ The dog was laid on its back and the bone marrow taken from the chest bone. -

ECVAM Statement on the Scientific Validity of the EPISKIN Test

European Commission ECVAM, TP 580 JRC Environment Institute 21020 Ispra (VA) Italy ECVAM European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods STATEMENT ON THE SCIENTIFIC VALIDITY OF THE EPISKINTM TEST (AN IN VITRO TEST FOR SKIN CORROSIVITY) At its 10th meeting, held on 31 March 1998 at the European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods (ECVAM), Ispra, Italy, the ECVAM Scientific Advisory Committee (ESAC)1 unanimously endorsed the following statement: The results obtained with the EPISKINTM test (involving the use of a reconstructed human skin model) in the ECVAM international validation study on in vitro tests for skin corrosivity were reproducible, both within and between the three laboratories that performed the test. The EPISKIN test proved applicable to testing a diverse group of chemicals of different physical forms, including organic acids, organic bases, neutral organics, inorganic acids, inorganic bases, inorganic salts, electrophiles, phenols and soaps/ surfactants. The concordances between the skin corrosivity classifications derived from the in vitro data and from the in vivo data were very good. The test was able to distinguish between corrosive and non corrosive chemicals for all of the chemical types studied; it was also able to distinguish between known R35 (UN2 packing group I) and R34 (UN packing groups II & III) chemicals. The Committee therefore agrees with the conclusion from this formal validation study that the EPISKIN test is scientifically validated for use as a replacement for the animal test, -

How Food Not Bombs Challenged Capitalism, Militarism, and Speciesism in Cambridge, MA Alessandra Seiter Vassar College, [email protected]

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Veganism of a different nature: how food not bombs challenged capitalism, militarism, and speciesism in Cambridge, MA Alessandra Seiter Vassar College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Seiter, Alessandra, "Veganism of a different nature: how food not bombs challenged capitalism, militarism, and speciesism in Cambridge, MA" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 534. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Veganism of a Different Nature How Food Not Bombs Challenged Capitalism, Militarism, and Speciesism in Cambridge, MA Alessandra Seiter May 2016 Senior Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts degree in Geography _______________________________________________ Adviser, Professor Yu Zhou Table of Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1: FNB’s Ideology of Anti-Militarism, Anti-Capitalism, and Anti-Speciesism ............ 3 Chapter 2: A Theoretical Framework for FNB’s Ideology .......................................................... 19 Chapter 3: Hypothesizing FNB’s Development -

Accountability

ACCOUNTABILITY animal experiments & freedom of information The assessment of projects under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 The licensing process The Animal Procedures Committee The application of Nolan principles ACCOUNTABILITY animal experiments & freedom of information - a parliamentary briefing CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. Background 2 3. Secrecy vs Transparency 5 4. Put it to the test 9 5. The Animal Procedures Committee 13 6. Reform of the APC 16 7. Local Ethics Committees 21 8. Conclusions 25 Appendix: Profile of current members of the APC 261 Goldhawk Road, London W12 9PE. Tel. 0181 846 9777 Fax. 0181 846 9712 e-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.cygnet.co.uk/navs ©NAVS 1997 ACCOUNTABILITY 1. Introduction There is undoubtedly considerable public disquiet that cruel, unnecessary or repetitive research continues on animals in British laboratories. Bland government assurances that our legislation is the ‘best in the world’ do not convince a public now familiar with video and photographic evidence of the reality of animal experimentation. The secrecy with which the law is administered only hardens the conviction that there is something to hide. Well documented evidence from the NAVS and others has shown that government guidelines and the ‘Code of Practice for the Housing and Care of Laboratory Animals’ are not diligently enforced and that the Home Office leans towards protection of vivisection industry interests rather than towards serving the public will. It has taken undercover investigations to expose serious abuses within the system. In March 1997 a Channel 4 investigation led to the threat of the revocation of the Certificate of Designation for Huntingdon Life Sciences and the prosecution of former staff members. -

Perspectives

PERSPECTIVES several organizations that were set up to SCIENCE AND SOCIETY continue the campaign. In both the United States and Europe, the debate about animal experimentation waned Animal experimentation: with the advent of the First World War, only to re-emerge during the 1970s, when anti- the continuing debate vivisection and animal-welfare organizations joined forces to campaign for new legislation to regulate animal research and testing. In the Mark Matfield United States, the public debate re-emerged in a more dramatic fashion in 1980, when an The use of animals in research and there was considerable protest from some activist infiltrated the laboratory of Dr Edward development has remained a subject of members of the audience and that, after one Taub of the Institute of Behavioural Research public debate for over a century. Although animal had been injected, an eminent med- at Silver Spring, Maryland (BOX 1). This attack there is good evidence from opinion surveys ical figure summoned the magistrates to on Taub’s research was organized by a tiny that the public accepts the use of animals in prevent the demonstration from continuing. animal-rights group called People for the research, they are poorly informed about the The Royal Society for the Prevention of Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), which way in which it is regulated, and are Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) brought a pros- has since grown to dominate the campaign in increasingly concerned about laboratory- ecution for cruelty, and several of the doctors the United States. animal welfare. This article will review how present at the demonstration gave evidence public concerns about animal against Magnan, who returned to France to The anatomy of the campaign experimentation developed, the recent avoid answering the charges. -

Trial by Fire: the SHAC7, Globalization, and the Future of Democracy

1 Trial By Fire: The SHAC7, Globalization, and the Future of Democracy Steven Best and Richard Kahn† "The FBI has made the prevention and investigation of animal rights extremists and eco-terrorism ...a domestic terrorism investigative priority." -- John E. Lewis, Deputy Assistant FBI Director in Counterterrorism, speaking to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, May 2004 “Ah, but in such an ugly time, the true protest is beauty.” -- Phil Ochs, Songwriter Since 1999, Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC) activists have waged an aggressive direct action campaign against Huntingdon Life Sciences (HLS), an insidious UK animal testing company notorious for its extreme animal abuse (torturing and killing 500 animals a day, 180,000 a year), sloppy research methods, and manipulated data.1 By combining a shrewd knowledge of the law, no nonsense direct action tactics, savvy use of new media like the Internet to coordinate campaigns, and a singular focus on eliminating HLS as a chief representative of the evils of the vivisection industry, SHAC has proven itself to be not only a leading animal rights organization, but also a contemporary model of anti-corporate resistance on a global level. As such, SHAC’s strategy and methodological approach must be understood as highly relevant for all manners of contemporary political struggle, be they for human rights, animal rights, or the environment. From email and phone blockades to raucous home demonstrations and sabotage strikes, so-called “SHACtivists” have demonstrated vigorously against HLS and likewise pressured over 100 other companies to abandon their financial ties to the vivisection firm. In this way, by 2001, the SHAC movement drove down HLS stock values from $15/share to less than $1/share, threatened it with ______________________________ †Dr. -

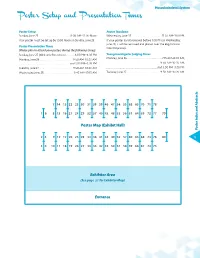

Poster Setup and Presentation Times

Musculoskeletal System Poster Setup and Presentation Times Poster Setup Poster Teardown Sunday, June 25 ...........................................8:00 AM–12:00 Noon Wednesday, June 28......................................... 11:30 AM–1:00 PM Your poster must be set up by 12:00 Noon on Sunday, June 25. If your poster is not removed before 1:00 PM on Wednesday, June 28, it will be removed and placed near the Registration Poster Presentation Times Desk for pickup. (Please plan to attend your posters during the following times). Sunday, June 25 (Welcome Reception) ............6:00 PM–6:30 PM Young Investigator Judging Times Monday, June 26 ............................................ 9:50 AM–10:20 AM Monday, June 26 ...............................................7:15 AM–8:00 AM, ....................................................................and 3:00 PM–3:30 PM ........................................................................ 9:50 AM–10:20 AM, Tuesday, June 27 ............................................. 9:50 AM–10:20 AM ....................................................................and 3:00 PM–3:30 PM Wednesday, June 28........................................ 9:45 AM–10:15 AM Tuesday, June 27 ............................................. 9:50 AM–10:20 AM 7 14 15 22 23 30 31 38 39 46 47 54 55 62 63 70 71 78 1 6 8 13 16 21 24 29 32 37 40 45 48 53 56 61 64 69 72 77 79 Poster Map (Exhibit Hall) Poster Index and Abstracts Poster 2 5 9 12 17 20 25 28 33 36 41 44 49 52 57 60 65 68 73 76 80 1 3 4 10 11 18 19 26 27 34 35 42 43 50 51 58 59 66 67 74 75 Exhibitor Area (See page 37 for Exhibitor Map). -

Dear Participants of the 5Th World Congress on Alternatives And

Abstracts001-Edi 24.07.2005 12:17 Uhr Seite 1 EDITORIAL Dear Participants of the 5th World Congress on Alternatives and Animal Use in the Life Sciences, The abstract book contains 614 abstracts of the plenary lectures of 272 oral presentations and 342 posters to be presented at the 5th World Congress on Alternatives in August 2005 in Berlin, Germany. The programme and the abstract book allow you to make your best selection of presentations among seven themes, which will be discussed in 29 sessions, 15 workshops and in the poster sessions. Usually, the first author of an abstract is slotted to give the oral presentation or to be present during the poster session to discuss your comments and questions. Otherwise, the presenting author is marked with an asterisk (*). We hope that you will find the abstracts particularly helpful to set priorities when two or more sessions are scheduled at the same time. In case you do not manage to attend a session or to meet an author, the contact addresses are given for each contributor. It is obvious from the list of sponsors, the programme and from the number of abstracts submitted that the most important topic of the 5th World Congress will be in vitro testing of cosmetic ingredients, in particular acute local toxicity testing. More abstracts have been submitted to sessions and workshops of Theme 5 “Safety testing, validation and risk assessment” than to any of the other themes. Moreover, more than 60 abstracts have been submitted to session 5.4 “Development and validation of alternatives for dermal toxicity testing”. -

Sorenson Interview with Ronnie

The Brock Review Volume 12 No. 1 (2011) © Brock University Interview with Ronnie Lee John Sorenson Ronnie Lee is widely-respected among activists as one of the founding members of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) in the 1970s and for creating the now-discontinued magazine Arkangel in 1989. Lee joined the Hunt Saboteurs Association in the 1970s and in 1973 created another organization, the Band of Mercy (taking its name from the nineteenth-century anti-hunting youth groups organized by the RSPCA). The Band of Mercy was based on the idea of direct action, including the destruction of property used to harm animals, but its principles emphasized that no violence should be directed against humans. In 1974 Lee was sentenced to prison for rescuing animals from gruesome vivisection practices at the Oxford Animal Laboratory in Bicester; while in prison he was forced to go on a hunger strike to obtain vegan food. After being released from prison, Lee started the ALF, which operates under the following guidelines: • To liberate animals from places of abuse, i.e., laboratories, factory farms, fur farms, etc., and place them in good homes where they may live out their natural lives, free from suffering. • To inflict economic damage to those who profit from the misery and exploitation of animals. • To reveal the horror and atrocities committed against animals behind locked doors, by performing direct actions and liberations. • To take all necessary precautions against harming any animal, human and non-human. • Any group of people who are vegetarians or vegans and who carry out actions according to these guidelines have the right to regard themselves as part of the Animal Liberation Front. -

Download PDF Version

Volume 5, OCTOBER 2010 THE Global Research Education and Training, LLC •57 S. Main Street, #190, Neptune, NJ 07753-5032 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.gr8tt.com R e c o R d In ThIs Issue: Does Lack of Enrichment Invalidate Scientific Data Obtained from Rodents? Great Posters! 4 SPRING 2010 | ENRICHMENTRECORD.COM THE R e c o R d IN THIS ISSUE | October 2010 1 edIToRIAL BoARd 2 Tim Allen, M.S. Animal Welfare Information Center Environmental Enrichment Fights Cancer and Improves Research 4 Genevieve Andrews-Kelly, B.S., LATG Results—What Now for the Biomedical Researcher? Huntingdon Life Sciences Elizabeth Dodemaide, B.V.Sc., M.A., MACVSc What’s Going On With the New Draft Version of The Guide? 6 Associate Director, Laboratory Animal Services Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Canine Socialization Through the Use of “Playrooms” or Exercise Rooms 7 Karen Froberg-Fejko, V.M.D., President, Bio-Serv Does Lack of Enrichment Invalidate Scientific Data 10 Joanne Gere, Founder, BioScience Collaborative Obtained from Rodents? G. Scott Lett, Ph.D., CEO, The BioAnalytics Group LLC Jayne Mackta 13 President & CEO, Global Research Education & Training LLC Emily G. Patterson-Kane, Ph.D. Posters: American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) European (EU) Compliant Housing Environment 14 Animal Welfare Division for Nonhuman Primates in a Toxicology Laboratory Kathleen L. Smiler, D.V.M., DACLAM Consultant, Laboratory Animal Medicine Effects of International Transit and Relocation 15 on Cortisol Values in Cynomolgus Macaques Rhoda Weiner, Weiner & Associates Joanne Zurlo, Ph.D. Director of Science Strategy The Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT) Upcoming Meetings 16 Please direct all inquiries to Rhoda Weiner, Editor: [email protected] Join the Discussion! To facilitate informed discussion about environmental enrichment, we have We’d Love To heAR fRom you! joined the Linkedin Group called Laboratory Animal Sciences.