Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oscar Hammerstein II Collection

Oscar Hammerstein II Collection Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2018 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2014565649 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu018003 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2018 Collection Summary Title: Oscar Hammerstein II Collection Span Dates: 1847-2000 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1920-1960) Call No.: ML31.H364 Creator: Hammerstein, Oscar, II, 1895-1960 Extent: 35,051 items Extent: 160 containers Extent: 72.65 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2014565649 Summary: Oscar Hammerstein II was an American librettist, lyricist, theatrical producer and director, and grandson of the impresario Oscar Hammerstein I. The collection, which contains materials relating to Hammerstein's life and career, includes correspondence, lyric sheets and sketches, music, scripts and screenplays, production materials, speeches and writings, photographs, programs, promotional materials, printed matter, scrapbooks, clippings, memorabilia, business and financial papers, awards, and realia. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the LC Catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically. People Brill, Leighton K.--Correspondence. Buck, Pearl S. (Pearl Sydenstricker), 1892-1973--Correspondence. Buck, Pearl S. (Pearl Sydenstricker), 1892-1973. Crouse, Russel, 1893-1966. -

Mindsweep 2.0 – Questions I

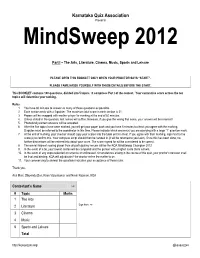

Karnataka Quiz Association Presents MindSweep 2012 Part I – The Arts, Literature, Cinema, Music, Sports and Leisure PLEASE OPEN THIS BOOKLET ONLY WHEN YOUR PROCTOR SAYS “START”. PLEASE FAMILIARISE YOURSELF WITH THESE DETAILS BEFORE THE START. This BOOKLET contains 100 questions, divided into 5 topics. It comprises Part I of the contest. Your cumulative score across the ten topics will determine your ranking. Rules: 1. You have 60 minutes to answer as many of these questions as possible. 2. Each section ends with a 2-pointer. The maximum total score in each section is 21. 3. Papers will be swapped with another player for marking at the end of 60 minutes. 4. Unless stated in the question, last names will suffice. However, if you give the wrong first name, your answer will be incorrect! 5. Phonetically correct answers will be accepted. 6. After the five topics have been marked, you will get your paper back and you have 5 minutes to check you agree with the marking. Disputes must be referred to the coordinator in this time. Please indicate which answer(s) you are querying with a large ―?‖ question mark. 7. At the end of marking, your checker should copy your scores into the table on this sheet. If you agree with their marking, sign next to the score(s) to confirm this. Your complete script should then be handed in (it will be returned to you later). Once this has been done, no further discussions will be entered into about your score. The score signed for will be considered to be correct. -

News from the Library of Congress

News from the Library of Congress Music OCLC Users Group Annual Meeting Music Library Association Annual Meeting St. Louis, Missouri, February 19-23, 2019 Music Division Collection Development During fiscal year 2018 (October 1, 2017-September 20, 2018), specialist staff continued to engage in a wide range of collection development activities toward establishing and achieving the set annual acquisition strategies for digital and non-digital materials. These activities included updating the top desiderata list; identifying research areas/subjects to be enhanced and/or specific collections/items to be acquired -- through contact with such sources of potential acquisitions as donors, collectors, dealers, government agencies, collecting institutions, and auction houses. This year’s top desiderata list continued to focus on important collections of American figures in Broadway, song-writing, jazz, and dance. Film music has been added to this list of desiderata. The Acquisitions Committee continued to strategize over random and unforeseen opportunities for manuscript items that related significantly to our collections. Analysis of research value and the fitness for our collections remain paramount concerns for acquisitions. Acquisition trips have been very fruitful for identifying materials the Library does not need as well as identifying potential conservation issues. The Division has also considered appropriate items on sites such as eBay. Each year incoming acquisitions statistics swing wildly from one extreme to another – mainly due to the size of a particular collection or collections. Last year saw the arrival of the Billy Strayhorn Papers, a collection estimated originally at about 8,000 items. Because of document counting practices, the number doubled to 17,700, reflected by the processing of financial papers and other documents. -

FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini

Pat McCorkle, CSA Jeffrey Dreisbach, Casting Partner Katja Zarolinski, CSA Kristen Kittel, Casting Assistant FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini. Starring: William Shatner, Christopher Lloyd, Jean Smart. THE MURPHYS (Independent Feature; Producer(s): The Murphy's LLC). Director: Kaitlan McGlaughlin. BERNARD & HUEY (In production. Independent Feature; Producer(s): Dan Mervish/Bernie Stein). Director: Dan Mervish. AFTER THE SUN FELL (Post Production. Independent feature; Producer(s): Joanna Bayless). Director: Tony Glazer. Starring: Lance Henriksen, Chasty Ballesteros, Danny Pudi. FAIR MARKET VALUE (Post Production. Feature ; Producer(s): Judy San Romain). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Jerry Adler, D.C. Anderson, Michael J. Arbouet. YEAR BY THE SEA (Festival circuit. Feature; Producer(s): Montabella Productions ). Director: Alexander Janko. Starring: Karen Allen, Yannick Bisson, Michael Cristofer. CHILD OF GRACE (Lifetime Network Feature; Producer(s): Empathy + Pictures/Sternamn Productions). Director: Ian McCrudden. Starring: Ted Lavine, Maggy Elizabeth Jones, Michael Hildreth. POLICE STATE (Independent Feature; Producer(s): Edwin Mejia\Vlad Yudin). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Sean Young, Seth Gilliam, Christina Brucato. MY MAN IS A LOSER (Lionsgate, Step One Entertainment; Producer(s): Step One of Many/Imprint). Director: Mike Young. Starring: John Stamos, Tika Sumpter, Michael Rapaport. PREMIUM RUSH (Columbia Pictures; Producer(s): Pariah). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. JUNCTION (Movie Ranch; Producer(s): Choice Films). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. GHOST TOWN* (Paramount Pictures; Producer(s): Dreamworks SKG). Director: David Koepp. Starring: Ricky Gervais, Tea Leoni, Greg Kinnear. WAR EAGLE (Empire Film; Producer(s): Downstream Productions). Director: Robert Milazzo. Starring: Brian Dennehy, Mary Kay Place, Mare Winningham. -

The Nordic Region for All

THE NORDIC REGION FOR ALL Nordic co-operation on universal design and accessibility Published by the Nordic Centre for Welfare www.nordicwelfare.org © May 2016 (updated and translated into English in September 2016) Part of the ”Disability perspective, gender and diversity” project Author: Maria Montefusco [email protected] Publisher: Ewa Persson Göransson ISBN: 978-91-88213-07-5 Edition: 300 Graphic design: Idermark och Lagerwall Reklam AB Press: TB Screen AB The report can be downloaded from www.nordicwelfare.org/publikationer CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 5 Summary and recommendations for co-operation for a nordic region with better universal design ...................................................... 6 Summary and expert group recommendations for cooperation on a more universally designed Nordic region .................................... 8 Value added through nordic co-operation on universal design and accessibility .................................................................................. 10 Members of the expert panel on universal design and accessibility ......................................................................................... 12 EQUAL OPPORTUNITY, ACCESSIBILITY AND SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ................................................................. 14 The value of universal design ............................................................. 14 3 The nordic welfare model and universal design -

LGBTQ+ Artists Represented Int the Performing Arts Special Collections

LGBTQ+ Artists Represented in the Performing Arts Special Collections in the Library of Congress Music Division Aaron Copland with Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti, 1945 (Aaron Copland Collection, Box 479 Folder 3) Compiled by Emily Baumgart Archives Processing Technician January 2021 Introduction The artistic community has always had many LGBTQ+ members, including musicians, dancers, choreographers, writers, directors, designers, and other creators. The Music Division holds a wealth of information about these LGBTQ+ artists in its performing arts special collections, which contain musical scores, correspondence, scripts, photographs and other documents of their lives and careers. This survey brings together some of the highlights from these holdings, providing an opportunity to learn more about LGBTQ+ creators and to recognize and celebrate their artistic achievements. The sexual and gender identity of many historical figures has been obscured over time; moreover, it can be difficult to determine how such individuals would identify by today’s terminology, especially when little of their personal life is known. Other figures, however, have disclosed their identity through their private correspondence or other writings. We do not wish to ascribe to any person an identity that they may have disagreed with, but at the same time we recognize that many of the queer community’s accomplishments have been hidden through oppression, prejudice, and forced closeting. By increasing awareness of LGBTQ+ identity in the Music Division’s special collections, we can make relevant primary source materials more readily accessible for students, educators, and scholars to study these creators and their contributions. This survey does not claim to be comprehensive, neither in terms of identifying every LGBTQ+ artist within the Music Division’s special collections nor in terms of identifying every collection in which those artists are represented. -

O'casey, Sean List 75

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 75 Sean O’Casey Papers (MS 37,807 - MS 38,173, MS L 93) Accession No. 5716 Correspondence between Sean O’Casey and academics, agents, writers, theatre producers, actors, friends, fans and others. Also; copy articles, notes, sketches and proofs, along with press cuttings and production programmes from Ireland, Britain, Europe and North America. Compiled by Jennifer Doyle, 2003 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Select Bibliography 8 I. Correspondence 9 I.i. Academics, Students & Librarians 9 I.ii. Actors 39 I.iii. Agents & Publishers 45 I.iv. Artists, Designers & Musicians 66 I.v. Awards and Honours 70 I.vi. Business and Financial Affairs 72 I.vi.1. Domestic 72 I.vi.2 Royalties & Tax 73 I.vii. Clerics 77 I.viii. Critics 82 I.ix. Family 90 I.x. Fan Mail and Unsolicited Letters 92 I.xi. Friends 104 I.xii. Gaelic League and St Laurence O’Toole Pipe Band 111 I.xiii. Invitations and Requests 114 I.xiii.1. Political 114 I.xiii.2. Charitable 124 I.xiii. 3. Literary 126 I.xiii. 4 Social 137 I.xiv. Labour Movement 140 I.xv. Magazines and Periodicals 150 I.xvi. Newspapers 166 I.xvii. Theatre, Film and other Productions 181 I.xvii.1 Theatre Producers & Directors (alphabetically by individual) 198 I.xvii.2. Film & Recording 220 I.xvii.3. Television and Radio 224 I. xviii. Translations 232 I.xix. Women 236 I.xx. Writers - Aspiring 240 I.xxi. Writers 241 I.xxi.1. Union of Soviet Writers 257 II. -

Nordic Collaboration Is Greater Than Ever, Pages 6-7

NORDVISION I TAL 2016 1 Annual Report 2017-2018 English version nordvision NEW RECORD: Nordic collaboration is greater than ever, pages 6-7 HISTORIC MUSKETEERS’ OATH on Nordic drama, pages 20-21 SKAM MUST DIE - long live SKAM, pages 46-47 18 Editorial team: Secretary General Henrik Hartmann (Chief Editor) Journalist Ib Keld Jensen (Co-Editor) Project Manager Kristian Martikainen Project Manager Øystein Espeseth-Andresen Contents Journalist Michaela von Kügelgen Journalist Randi Lillealtern Designer Lars Schmidt Hansen Introduction 4-5 Another record year 6-7 Photos: Looking back: 2017 figures 8-9 30 Front cover: Den døende detektiv: Peter Cederling/SVT Content collaboration Herrens veje: Tine Harden/DR Snöfall: NRK Children 10 Drama 18 Page 3 Factual 26 Baldur Bragason@Filmlance Int / Nimbus Film, Mystery Productions for RUV, Culture 30 Jonas Bendiksen, DR Undervisning, NRK Investigative journalism 36 12 Youth & young adults 44 Back cover: The Independence Day: Yle Drama Knowledge 50 Samernes tid: Susanna Hætta Programme exchange 56 Reimleikar: RUV Nyt rekordår Sig mig engang: Har jeg ikke læst den artikel før? ”Antallet samproduktioner er over alle forventninger ikke mindst fokuseret på færre, men større og vigtigere public service-opgaver Hvis læsere af Nordvisions årsrapport sidder tilbage med en set i lyset af, at alle de nordiske public service tv-stationer er i gang det kommende år, og det jo også kommer til at smitte af på samarbejdet, Knowledge exchange 62 fornemmelse af deja vu, så er der ikke noget at sige til det. med en digital transformation. Dermed producerer de mindre flow når det gælder volumen,” påpeger hun. -

Øyne På Broadway Amerikansk Innflytelse På Musikalscenen I Norge

54 ALLES ØYNE PÅ BROADWAY AMERIKANSK INNFLYTELSE PÅ MUSIKALSCENEN I NORGE SIGRID ØVREÅS SVENDAL Verdens teatersjefer ser mot Broadway. Oktober 1958 blir alle tiders største sesong, er det forkynt fra teatrets Mekka, Broadway. Og det er ikke til å undre seg over at alle verdens teatersjefer følger rapportene fra New Yorks teatergate, som var det deres egen feberkurve. 74 prosent av alle uroppførte stykker i Europa har startet sitt sei- ersløp nettopp på Broadway.1 Teaterrepertoaret i Norge i de første tiårene etter 1945 viser tydelig at amerikan- ske musikaler dominerte de store scenene. Oklahoma!, Showboat, Kiss me Kate, Annie get your gun, My Fair Lady og West Side Story ble raskt både økonomiske og publikumsmessige suksesser. Disse musikalene hadde alle skandinaviske premi- erer i perioden 1949 til 1965. Norge var ikke enestående, tvert i mot, de ameri- kanske musikalene var sterkt synlige i store deler av Europa etter 1945, i en tid hvor amerikansk kultur generelt hadde stor betydning.2 Betyr dette at de norske teatrene ble amerikanisert i tiårene etter andre verdenskrig? I denne artikkelen vil jeg se nærmere på hvorfor de amerikanske musikalene ble så populære som de ble. Artikkelens første del vil kartlegge hvordan musika- lene fant veien fra USA til Norge, og med det identiisere hvilke overføringskana- ler som var de viktigste. Musikalene Kiss me Kate og West Side Story brukes som illustrerende eksempler. Jeg vil også diskutere om musikalene ble ansett som po- pulærkultur. Artikkelens andre del tar for seg mulig årsaker til at de amerikanske musikalene ble så dominerende som de ble. Kan populariteten forklares med det amerikanske kulturdiplomatiet under den kalde krigen, som i stor skala sendte ut amerikanske kulturuttrykk til resten av verden? Dersom musikaler utgjorde en viktig del av kulturdiplomatiet, kan det ha bidratt til gjennomslaget musikalene 1 Verdens Gang (VG) 10.10.1958: ”Verdens teatersjefer ser mot Broadway”. -

Johan Franzon – Dokumenterat 48 2016

DOKUMENTERAT 48 38 Från en vrå för två till en sommar i Ohio Svenska musikalöversättare 1930–2013 Johan Franzon1 Den kanske första, länge enda boken ägnad helt åt musikteateröversättning skrevs 1978 av Kurt Honolka. Han använde begreppet »Operndeutsch« för att karakterisera ett slags översättningsspråk som alla operaälskare borde ogilla: svulstigt, kitschigt och onaturligt.2 Det dröjde, men så sakta har diskussion av sång i översättning växt till ett forskningsintresse. Det är som ett erkännande när en forskningsöversikt publiceras i en stor, över- sättningsvetenskaplig handbok,3 och som en explosion när två böcker i ämnet utkommer samma år: en om operaöversättning och en om hur sångtexter översätts för olika syften, inte bara sångbart.4 På svenska har det skrivits en del om operaöversättning, men en ny bok kunde gärna få komplettera Bengt Haslums gamla, lättsamma operett- och musikalbok från 1979 och Nordströms nyare men ännu mer lättsamma och inkom- pletta illustrerade verköversikt.5 Frågorna som först infinner sig när det gäller denna typ av textarbete är: Hur gör man? Vad krävs för att lyckas med ett så särdeles knepigt, multimedialt översättaruppdrag? Vari består svårigheterna och vilka strategier kan översättare ta till? Men det vore också värt att fråga: Kan man urskilja trender och tendenser i hur musikaler har översatts till svenska under 1900-talet? Kan man spåra förändringar till exempel i fråga om det amerikanska kulturinflytandet, respekten för genren eller synen på sång: som seriös dramatik eller underhållning? Går det att karakterisera en textsort som ’musikalsvenska’? Vad innebär det att sätta nya ord till en sångtext som är djupt inbäd- dad i både en viss musikalisk komposition och en teateruppsättning? Åtminstone den frågan har jag tidigare sökt besvara övergripande, genom 1. -

Gindt Selected CV and Publications

Dr Dirk Gindt CURRICULUM VITAE [email protected] EDUCATION AND DEGREES 2007: Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, SubJect: Theatre Studies, Stockholm University, Sweden (awarded 5 November 2007) 2002: Master of Arts with a MaJor in Theatre History and Theory, Stockholm University, Sweden (awarded 20 June 2002) 1995: Diplôme de fin d’études secondaires, enseignement moderne, orientation littéraire, section langues vivantes. Lycée Hubert Clément, Esch-sur-AlZette, Luxembourg (awarded June 1995) PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Jan 2020 –: Professor of Theatre Studies, Department of Culture and Aesthetics, Stockholm University, Sweden Sept 2015 – Dec 2019: Associate Professor (docent), tenured-on-appointment, Theatre Studies, Department of Culture and Aesthetics, Stockholm University, Sweden Sept 2014 – April 2015: Lecturer, Department of Theatre, Concordia University, Montréal, Canada Jan 2013 – May 2014: Visiting Scholar/Artist-in-Residence, Department of Theatre, Concordia University, Montréal, Canada 2012: Promotion to Associate Professor (docent), Theatre Studies, Stockholm University, Sweden (effective 10 October 2012) Nov 2011 – June 2013: Research Fellow (forskarassistent), Theatre Studies, Department of Musicology and Performance Studies, Stockholm University, Sweden Dec 2009 – Oct 2011: Post-Doctoral Associate (postdoc), Centre for Fashion Studies, Stockholm University, Sweden Feb 2008 – Nov 2009: Assistant Professor (universitetslektor), contractually limited: Centre for Fashion Studies, Stockholm University April 2006 – Dec 2007: Instructor -

Arvinge Okänd

Annual Report 2018-2019 nordvision English version Drama for youth and young adults is a hit: Tremendous growth p. 32 Nordic collaboration: Four seminars become annual events p. 46 SVT Factual format goes Nordic: Huge interest in finding unknown heirs p. 24 Investigative journalism: Working together to cover cross-border stories p. 30 NORDVISION 2018 - 2019 1 10 Editorial team: Henrik Hartmann (Editor in Chief) Ib Keld Jensen (Editor) Tommy Nordlund Contents Øystein Espeseth-Andresen Lars Schmidt Hansen Translation and proofreading: Rgnr Localisation Introduction 4 Looking back at 2018 figures 6 Print: New Chair of Nordvision 8 46 Front cover: Children 10 Line fikser kroppen (Photo: Kristin Granbo, NRK) Drama 14 Back cover: Factual 20 Culture 26 DR: I forreste række (Photo: DR) Investigative journalism 30 NRK: Heimebane (Photo: NRK) RUV: Hàsetar (Photo: RUV) Youth and young adults 32 SVT: Arvinge okänd (Photo: Stine Stjernkvist, SVT) News and sport 36 Yle: Jarkko och de döves Amerika (Photo: Petri Vilén, Yle) Programme exchange 40 KVF: Fisk & Skips (Photo: KVF) SR: Kolonien (Photo: Simon Moser) The past year 42 20 UR: Du är bäst (Photo: UR) Technology 44 30 KNR: Photo: Silje Bergum Kinsten, Norden.org Seminars 46 Overview and key figures 52 Contacts 62 32 Norwegians tuned in for an average of 78 minutes when Norway’s best-loved adventurer, Lars Monsen, hiked through the mountains for four weeks. He was accompanied by hundreds of interested followers as well as a TV crew of 30 carrying equipment constructed specially 6 for live broadcasts. This event marked the tenth anniversary of slow TV on NRK.