Laughing Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laughter: the Best Medicine?

Laughter: The Best Medicine? by Barbara Butler elcome to a crash COLI~SCin c~onsecli1~11cc.~ol'nvgarivc emotions. Third, Oregon Institute ofMarine Biology Gelotology 101. That isn't a using Iiumor as :I c~ol)irigs(r:itcgy n~ayalso University of Oregon typo, Gelotology (from the I~enefithealth inclirec.tly I)y moderating ad- Greek root gelos (to laugh)), is a term verse effects of stress. Finally, humor may coined in 1964 by Dr. Edith Trager and Dr. provide another indirect Ixnefit to health W.F. Fry to describe the scientific study of by increasing one's level of social support laughter. While you still can't locate this (Martin, 2002, 2004). term in the OED, you can find it on the Web. The study of humor is a science, The physiology of humor and laughter researchers publish in the Dr. William F. Fry from Stanford University psychological and physiological literature has published a number of studies of the as well as subject specific journals (e.g., physiological processes that occur dur- Humor: International Journal of Humor ing laughter and is often cited by people Research). claiming that laughter is equivalent to ex- While at the Special Libraries As- ercise. Dr. Fry states, "I believe that we do sociation annual conference last June, I not laugh merely with our lungs, or chest was able to attend a session by Elaine M. muscles, or diaphragm, or as a result of a Lundberg called Laugh For the Health of stimulation of our cardiovascular activity. It. The room was packed and she had the I believe that we laugh with our whole audience laughing and learning for the physical being. -

Two Studies on the Social Function of Joking As an Outlet for Aggression. John W

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1967 Two Studies on the Social Function of Joking as an Outlet for Aggression. John W. Dresser Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Dresser, John W., "Two Studies on the Social Function of Joking as an Outlet for Aggression." (1967). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1243. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1243 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO STUDIES ON THE SOCIAL FUNCTION OF JOKING AS AN OUTLET FOR AGGRESSION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Psychology by John W. Dresser B.A., Pomona College, 1958 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1962 January, 1967 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to express his deep appreciation to his major professor, Dr. Robert N. Vidulich, for his advice and en couragement throughout the course of this research, and for his confidence and generous support throughout the author's doctoral program. Particular thanks are also due Dr. Roland L. Frye for his advice on statistical aspects of the present research. A very special appreciation is owed the author's wife, Mrs. -

The Absurd Author(S): Thomas Nagel Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Journal of Philosophy, Vol

Journal of Philosophy, Inc. The Absurd Author(s): Thomas Nagel Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 68, No. 20, Sixty-Eighth Annual Meeting of the American Philosophical Association Eastern Division (Oct. 21, 1971), pp. 716-727 Published by: Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2024942 . Accessed: 19/08/2012 01:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Philosophy, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Philosophy. http://www.jstor.org 7i6 THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY The formerstands as valid only if we can findcriteria for assigning a differentlogical formto 'allegedly' than to 'compulsively'.In this case, the criteriaexist: 'compulsively'is a predicate, 'allegedly' a sentenceadverb. But in countless other cases, counterexamplesare not so easily dismissed.Such an example, bearing on the inference in question, is Otto closed the door partway ThereforeOtto closed the door It seems clear to me that betterdata are needed beforeprogress can be made in this area; we need much more refinedlinguistic classificationsof adverbial constructionsthan are presentlyavail- able, ifour evidenceconcerning validity is to be good enough to per- mit a richerlogical theory.In the meantime,Montague's account stands: thereis no reason to thinka morerefined theory, if it can be produced, should not be obtainable within the frameworkhe has given us. -

The Incongruity of Incongruity Theories of Humor

THE INCONGRUITY OF INCONGRUITY THEORIES OF HUMOR Tomáš Kulka ABSTRACT: The article critically reviews the Incongruity Theory of Humor reaching the conclusion that it has to be essentially restructured. Leaving aside the question of scope, it is shown that the theory is inadequate even for those cases for which it is thought to be especially well suited – that it cannot account either for the pleasurable effect of jokes or for aesthetic pleasure. I argue that it is the resolution of the incongruity rather than its mere apprehension, which is that source of the amusement or aesthetic delight. Once the theory is thus restructured, the Superiority Theory of Humor and the Relief Theory can be seen as supplementary to it. KEYWORDS: Humor, Resolution of Incongruity Socrates: And when we laugh ... do we feel pain or pleasure? Protarchus: Clearly we feel pleasure. (Plato, Philebus, 50) In the literature on humor and laughter it is customary to distinguish between three classical theories: The Superiority Theory (Plato, Aristotle, Hobbes), the Relief Theory (Spencer, Freud) and the Incongruity Theory (Cicero, Kant, Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard).1 The three theories are usually seen as rivals, competing for the most plausible answers to ques- tions like: „Why do we laugh?“, „What is the nature of humor?“, or „What does the comical consist of?“ The Superiority Theory says that the comical is perceived as inferior and our laughter is an expression of the sudden realization of our superiority. The Relief Theory emphasizes the liberating effect of humor. Laughter is seen as a discharge of surplus energy which alleviates psy- chic tension. -

On Laughter Supervisor: Rebekah Humphreys Word Count: 21991

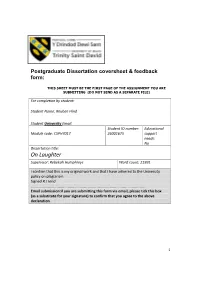

Postgraduate Dissertation coversheet & feedback form: THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by student: Student Name: Reuben Hind Student University Email: Student ID number: Educational Module code: CSPH7017 26001675 support needs: No Dissertation title: On Laughter Supervisor: Rebekah Humphreys Word count: 21991 I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed R J Hind …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Email submission:if you are submitting this form via email, please tick this box (as a substitute for your signature) to confirm that you agree to the above declaration. 1 ABSTRACT. Much of Western Philosophy has overlooked the central importance which human beings attribute to the Aesthetic experiences. The phenomena of laughter and comedy have largely been passed over as “too subjective” or highly emotive and therefore resistant to philosophical analysis, because they do not easily lend themselves to the imposition of Absolutist or strongly theory-driven perspectives. The existence of the phenomena of laughter and comedy are highly valued because they are viewed as strongly communal activities and expressions. These actually facilitate our experiences as inherently social beings, and our philosophical understanding of ourselves as beings, who experience passions and life itself amidst a world of fluctuating meanings and human drives. I will illustrate how the study of “Aesthetics” developed from Ancient Greek conceptions, through the post-Kantian and post-Romantic periods, which opened-up a pathway to the explicit consideration of the phenomena of laughter and comedy, with particular reference to the Apollonian/Dionysian conceptual schemata referred to in Nietzsche’s early works. -

Voltaire's Candide

CANDIDE Voltaire 1759 © 1998, Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project http://www.esp.org This electronic edition is made freely available for scholarly or educational purposes, provided that this copyright notice is included. The manuscript may not be reprinted or redistributed for commercial purposes without permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1.....................................................................................1 How Candide Was Brought Up in a Magnificent Castle and How He Was Driven Thence CHAPTER 2.....................................................................................3 What Befell Candide among the Bulgarians CHAPTER 3.....................................................................................6 How Candide Escaped from the Bulgarians and What Befell Him Afterward CHAPTER 4.....................................................................................8 How Candide Found His Old Master Pangloss Again and What CHAPTER 5...................................................................................11 A Tempest, a Shipwreck, an Earthquake, and What Else Befell Dr. Pangloss, Candide, and James, the Anabaptist CHAPTER 6...................................................................................14 How the Portuguese Made a Superb Auto-De-Fe to Prevent Any Future Earthquakes, and How Candide Underwent Public Flagellation CHAPTER 7...................................................................................16 How the Old Woman Took Care Of Candide, and How He Found the Object of -

The Persuasive Power of Ridicule: a Critical Rhetorical Analysis

THE PERSUASIVE POWER OF RIDICULE: A CRITICAL RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF GENDER AND HUMOR IN U.S. SITCOMS Leah E. Waters Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2017 APPROVED: Koji Fuse, Committee Chair Megan Morrissey, Committee Member James Mueller, Committee Member Dorothy Bland, Director of the Frank W. Mayborn Graduate Institute of Journalism and Dean of the Frank W. and Sue Mayborn School of Journalism Victor Prybutok, Vice Provost of the Toulouse Graduate School Waters, Leah E. The Persuasive Power of Ridicule: A Critical Rhetorical Analysis of Gender and Humor in U.S. Sitcoms. Master of Arts (Journalism), May 2017, 92 pp., 4 tables, references, 75 titles. The serious investigation of humor’s function in society is an emerging area of research in critical humor studies, a “negative” subsect of the extensive and “positive” research that assumes humor’s goodness. Using Michael Billig’s theory of ridicule as a framework, this study explored how humor operated to discipline characters who broke social norms or allowed characters to rebel against those norms. Layering this with gender performative theory, the study also investigated how different male and female characters used ridicule and were subject to it themselves. After examining ridicule in The Big Bang Theory, 2 Broke Girls, and The Odd Couple using a critical rhetorical analysis, the findings revealed that disciplinary ridicule was used more overtly throughout all three programs, while potentially rebellious ridicule emerged in only a few scenes. In addition, men were overwhelmingly the subjects of disciplinary ridicule, although women found themselves as subjects throughout all three programs as well. -

PERHAPS the Sentiments Contained in the Following Pages Are Not Yet Sufficiently Fashionable to Procure Them General Favor

LESSON: THOMAS PAINE, COMMON SENSE, 1776 FULL TEXT “for God’s sake, let us come New York Public Library to a final separation” Thomas Paine COMMON SENSE *January 1776 Presented here is the full text of Common Sense from the third edition (published a month after the initial pamphlet), plus the edition Appendix, now considered an integral part of the pamphlet’s impact. INTRODUCTION 1 PERHAPS the sentiments contained in the following pages are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor. A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason. 2 As a long and violent abuse of power is generally the Means of calling the right of it in question (and in Matters too Thomas Paine which might never have been thought of, had not the American Antiquarian Society Sufferers been aggravated into the inquiry), and as the King of England hath undertaken in his own Right to support the Parliament in what he calls Theirs, and as the good people of this country are grievously oppressed by the combination, they have an undoubted privilege to inquire into the preten- sions of both, and equally to reject the usurpation of either. 3 In the following sheets, the author hath studiously avoided everything which is personal among ourselves. Compliments as well as censure to individuals make no part thereof. The wise and the worthy need not the triumph of a pamphlet; and those whose sentiments are injudicious or unfriendly will cease of themselves unless too much pains are bestowed upon their conversion. -

Thomas Paine

I THE WRITINGS OF THOMAS PAINE COLLECTED AND EDITED BY MONCURE DANIEL CONWAY AUTHOR OF L_THE LIFR OF THOMAS PAINE_ y_ _ OMITTED CHAPTERS OF HISTOIY DI_LOSED IN TH I_"LIFE AND PAPERS OF EDMUND RANDOLPH_ tt _GEORGE W_HINGTON AND MOUNT VERNON_ _P ETC. VOLUME I. I774-I779 G. P. Pumam's Sons New York and London _b¢ "lkntckcrbo¢#¢_ I_¢ee COPYRIGHT, i8g 4 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Entered at Stationers' Hall, London BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS CONTENTS. PAGB INTRODUCTION V PREFATORY NOTE TO PAINE'S FIRST ESSAY , I I._AFRICAN SLAVERY IN AMERICA 4 II.--A DIALOGUE BETWEEN GENERAL WOLFE AND GENERAL GAGE IN A WOOD NEAR BOSTON IO III.--THE MAGAZINE IN AMERICA. I4 IV.--USEFUL AND ENTERTAINING HINTS 20 V._NEw ANECDOTES OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT 26 VI.--REFLECTIONS ON THE LIFE AND DEATH OF LORD CLIVE 29 VII._CUPID AND HYMEN 36 VIII._DUELLING 40 IX._REFLECTIONS ON TITLES 46 X._THE DREAM INTERPRETED 48 XI._REFLECTIONS ON UNHAPPY MARRIAGES _I XII._THOUGHTS ON DEFENSIVE WAR 55 XIII.--AN OCCASIONAL LETTER ON THE FEMALE SEX 59 XIV._A SERIOUS THOUGHT 65 XV._COMMON SENSE 57 XVI._EPISTLE TO QUAKERS . I2I XVII.--THE FORESTER'SLETTERS • I27 iii _v CONTENTS. PAGE XVIII.mA DIALOGUE. I6I XIX.--THE AMERICAN CRISIS . I68 XX._RETREAT ACROSS THE DELAWARE 38I XXI.--LETTER TO FRANKLIN, IN PARIS . 384 XXII.--THE AFFAIR OF SILAS DEANE 39S XXIII.--To THE PUBLm ON MR. DEANE'S A_FAIR 409 XXIV.mMEssRs. DEANS, JAY, AND G_RARD 438 INTRODUCTION. -

It's Dark. You Move Slowly, Creeping Through the Bushes, Putting Your Feet Down Carefully to Keep from Snapping Twigs Or Crunc

It’s dark. You move slowly, creeping through the bushes, putting your feet down carefully to keep from snapping twigs or crunching leaves. You try to stay just a few steps behind your friend Grok, just close enough to be able to make out through the darkness the ears on the wolf pelt draped across his shoulders. Suddenly, a noise, a twig snaps off to the left. Grok grunts under his breath. You stop; time does the same. Your spear feels heavy in your hand but you grip it tightly, tensing everything as you squat into an athletic stance. You grit your teeth and start taking shallow breaths into your chest as your heart pumps faster and your mind focuses, suddenly sharply aware of everything- internal and external. You stare at the spot where you heard the snapping, and you hear another, closer. You brace yourself; what will it be? Fight or flight? But then, through the darkness, you recognize the source of the sounds. As he comes closer, you realize it was your little brother, Robby. You smile, unclench your muscles, throw up your hands in relief, and you take deep, diaphragmatic breaths, adding just a slight vocalization so your friends will know everything’s okay and relax too, and then you all go back to thinking about different types of stone. In case you weren’t mentally acting it out as you read it, that process (with a few hundred thousand years of evolutionary refinement) is laughter, and this is its commonly accepted creation 1 myth. Laughter evolved as a way to relax upon discovering that a perceived and prepared for threat wasn’t real. -

The Misunderstood Philosophy of Thomas Paine

THE MISUNDERSTOOD PHILOSOPHY OF THOMAS PAINE A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of History Jason Kinsel December, 2015 THE MISUNDERSTOOD PHILOSOPHY OF THOMAS PAINE Jason Kinsel Thesis Approved: Accepted: ______________________________ _____________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Walter Hixson Dr. Chand Midha ______________________________ ______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Martino-Trutor Dr. Chand Midha ______________________________ ______________________________ Department Chair Date Dr. Martin Wainwright ii ABSTRACT The name Thomas Paine is often associated with his political pamphlet Common Sense. The importance of “Common Sense” in regards to the American Revolution has been researched and debated by historians, political scientists, and literary scholars. While they acknowledge that Paine’s ideas and writing style helped to popularize the idea of separation from Great Britain in 1776, a thorough analysis of the entirety of Paine’s philosophy has yet to be completed. Modern scholars have had great difficulty with categorizing works such as, The Rights of Man, Agrarian Justice, and Paine’s Dissertation on First Principles of Government. Ultimately, these scholars feel most comfortable with associating Paine with the English philosopher John Locke. This thesis will show that Paine developed a unique political philosophy that is not only different from Locke’s in style, but fundamentally opposed to the system of government designed by Locke in his Second Treatise of Government. Furthermore, I will provide evidence that Paine’s contemporary’s in the American Colonies and Great Britain vehemently denied that Paine’s ideas resembled those of Locke in any way. -

Aristotle's Ridicule of Political Innovation

Aristotle’s Ridicule of Political Innovation : PETERSON 119 Aristotle’s Ridicule of Political Innovation JOHN PETERSON The basic practical political question, constantly presented to every citizen in a republic, is whether to change or stay the same. The com- peting answers to the question may be said to constitute the essences of liberalism and conservatism, respectively. The constraints placed on the possibility of political change may be too great, as in tyranny, where nothing short of a revolution is sufficient; or too weak, as in extreme democracy, where every popular whim is effected. The need for the law to be reasonable and responsive must be balanced with the need for stability in the political order. We must ask ourselves whether we would put the particulars of our Constitution to a regular vote, or allow the wisest among us to replace it with what they deem better. That we balk at these suggestions demonstrates the commonsense Aristotelian understanding that law depends upon habit and tradition for its power and persuasiveness, and therefore that politics, contrary to the modern view, is not a science admitting of inflexible rules that can be applied according to precise formulae. When we treat it as such, we often make ourselves ridiculous by ignoring or downplaying the practical and par- ticular realities of politics. Aristotle addresses this question in his critique of Hippodamus in chapter 8 of book 2 of the Politics.1 There are three things to know about Hippodamus. First, he was the inventor of city planning (1267b21, 1330b23). Because of its reliance on method, this activity has important parallels to modern political science.