The Asian ESP Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OUTSTANDING WARRANTS As of 10/10/2017

OUTSTANDING WARRANTS as of 10/10/2017 AGUILAR, CESAR JESUS ALEXANDER, SARAH KATHEREN ALLEN, RYAN MICHAEL A AGUILAR, ROBERTO CARLOS ALEXANDER, SHARRONA LAFAYE ALLEN, TERRELL MARQUISE AARON, WOODSTON AGUILERA, ROBERTO ALEXANDER, STANLEY TOWAYNE ALLEN, VANESSA YVONNE ABABTAIN, ABDULLAH AGUILIAR, CANDIDO PEREZ ALEXANDER, STEPHEN PAUL ALMAHAMED, HUSSAIN HADI M MOHAMMED A AHMADI, PAULINA GRACE ALEXANDER, TERRELL ALMAHYAWI, HAMED ABDELTIF, ALY BEN AIKENS, JAMAL RAHEEM ALFONSO, MIGUEL RODRIGUEZ ALMASOUDI, MANSOUR ABODERIN, OLUBUSAYO ADESAJI AITKEN, ROBERT ALFORD, LARRY ANTONIO MOHAMMED ALMUTAIRI, ABDULHADI HAZZAA ABRAMS, TWANA AKIBAR, BRIANNA ALFREDS, BRIAN DANIEL ALNUMARI, HESHAM MOHSMMED ABSTON, CALEB JAMES AKINS, ROBERT LEE ALGHAMDI, FAHADAHMED-A ALONZO, RONY LOPEZ ACAMPORA, ADAM CHRISTOPHER AL NAME, TURKI AHMED M ALHARBI, MOHAMMED JAZAA ALOTAIBI, GHAZI MAJWIL ACOSTA, ESPIRIDION GARCIA AL-SAQAF, HUSSEIN M H MOHSEB ALHARBI, MOHAMMED JAZAA ALSAIF, NAIF ABDULAZIZ ACOSTA, JADE NICOLE ALASMARI, AHMAD A MISHAA ALIJABAR, ABDULLAH ALSHEHRI, MAZEN N DAFER ADAMS, ANTONIO QUENTERIUS ALBERDI, TOMMY ALLANTAR, OSCAR CVELLAR ALSHERI, DHAFER SALEM ADAMS, BRIAN KEITH ALBOOSHI, AHMED ABALLA ALLEN, ANDREW TAUONE ALSTON, COREY ROOSEVELT ADAMS, CHRISTOPHER GENE ALBRIGHT, EDMOND JERRELL ALLEN, ANTHONY TEREZ ALSTON, TORIANO ADARRYL ADAMS, CRYSTAL YVONNE ALCANTAR, ALVARO VILCHIS ALLEN, ARTHUR JAMES ALTMAN, MELIS CASSANDRA ADAMS, DANIEL KENNETH ALCANTAR, JOSE LUIS MORALES ALLEN, CHADWICK DONOVAN ALVARADO, CARLOS ADAMS, DARRELL OSTELLE ALCANTARA, JESUS ALLEN, CHRISTOPHER -

ANGELS in ISLAM a Commentary with Selected Translations of Jalāl

ANGELS IN ISLAM A Commentary with Selected Translations of Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī’s Al-Ḥabā’ik fī akhbār al- malā’ik (The Arrangement of the Traditions about Angels) S. R. Burge Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2009 A loose-leaf from a MS of al-Qazwīnī’s, cAjā’ib fī makhlūqāt (British Library) Source: Du Ry, Carel J., Art of Islam (New York: Abrams, 1971), p. 188 0.1 Abstract This thesis presents a commentary with selected translations of Jalāl al-Dīn cAbd al- Raḥmān al-Suyūṭī’s Al-Ḥabā’ik fī akhbār al-malā’ik (The Arrangement of the Traditions about Angels). The work is a collection of around 750 ḥadīth about angels, followed by a postscript (khātima) that discusses theological questions regarding their status in Islam. The first section of this thesis looks at the state of the study of angels in Islam, which has tended to focus on specific issues or narratives. However, there has been little study of the angels in Islamic tradition outside studies of angels in the Qur’an and eschatological literature. This thesis hopes to present some of this more general material about angels. The following two sections of the thesis present an analysis of the whole work. The first of these two sections looks at the origin of Muslim beliefs about angels, focusing on angelic nomenclature and angelic iconography. The second attempts to understand the message of al-Suyūṭī’s collection and the work’s purpose, through a consideration of the roles of angels in everyday life and ritual. -

Uriel: Communicating with the Archangel for Transformation and Tranquility Pdf, Epub, Ebook

URIEL: COMMUNICATING WITH THE ARCHANGEL FOR TRANSFORMATION AND TRANQUILITY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Webster | 240 pages | 18 Nov 2005 | Llewellyn Publications,U.S. | 9780738707037 | English | Minnesota, United States Uriel: Communicating with the Archangel for Transformation and Tranquility PDF Book One of the communications I have received from my angel is that the information I have gathered must be shared with others, and so I hope that this work forms a small addition to such stories and teachings of the world. As a literary figure, Angel Uriel has also left his mark. Angel Uriel. Yet, we often lack an understanding of their symbolic nature and the key characteristics that define them. If your fearful about world events, call upon Chamuel for comfort, protection, and intervention. Lifetime Achievement Award in recognition of a lifetime dedicated to excellence in writing magical literature. Psychic Chat. However, many Catholics still venerate Angel Uriel to this day. Have you heard of these words before? Put it off and be transfigured in the mighty transfiguring flame of life! Chapter seven covers how to work with the angelic realms. Your whole life, really, is simply a search for what it is you are supposed to do in this life, and then do it to the best of your ability! Entirely eloquent, and yet utterly ineffable. Guardian Angel Quotes. This image depicts an androgynous being with long hair and huge wings uplifted, wearing shining robes, often with a star glowing above its head. Next Article. The texts make it quite clear, however, that the Ka was not the soul, but rather a special divine being given to each person by the gods to protect the soul. -

37131054409156D.Pdf

YEZAD A Romance of the Unknown By GEORGE BABCOCK PUBLISHED BY CO-OPERATIVE PUBLISHING CO., INC. BRIDGEPORT, CONN. NEW YORK, N. Y. Copyright, November, 1922, by GEORGE BABCOCK All rights reserved To MY S1sTER, EVA STANTON (BABCOCK) BROWNING., this story 1s affectionately inscribed. GEORGE BABCOCK. Brooklyn, N. Y. November, 19ff. CHARACTERS l JOHN BACON, Aviator. 2 JuLIA BACON, His Wife. 3 PAUL BACON, Son. 4 ELLEN BACON, Daughter. 5 AnoLPH VON PosEN, Inventor, in love. 6 SALLY T1MPOLE, the Cook, also in love. 7 JASPER PERKINS } 8 SILAS CUMMINGS The old quaint cronies. 9 NANCY PRINDLE 10 DOCTOR PETER KLOUSE. 11 HESTER DOUGLASS} 12 F IN LEY D OU GLASS Grandchildren of the Doctor. 13 SAM WILLIS, the dreadful liar. 14 WILLIAM THADDEUS TITUS, Champion of several trades. 15 WILLIAM GRENNELL, the Village Blacksmith. 16 MINNA BACON } 17 B RENDA B ACON Children of Paul and Hester. 18 RoBERT DouGLAss, Son of Finley and Ellen. 19 CHARLOTTE Dun LEY, a Maiden of Mars. 20 CHRISTOPHER SPENCER, Astronomer of Mars. 21 FELIX CLAUDIO, the Devil's Son. 22 DocToR NATHAN ELIZABRAT of Mars. 23 MARCOMET, a Guard of the Great White \Vay. 24 JOHN BACON'S DUALITY. Note:-A Glossary of coined and unusual words and their mean ing, used by the author in Yezad, will be found on pages 449 to 463. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I THE PRICE OF PROGRESS 1 II THE GHOST • 20 III NEW NEIGHBORS 33 IV DOCTOR KLOUSE 45 V HEREDITY VS. KLOUSE PHILOSOPHY 52 VI A DREADFUL LIAR • 57 VII AMONG THE ABORIGINES 71 VIII AN ODD EXPERIMENT . -

Who Is Uriel the Archangel?

Who is Uriel The Archangel? The name Uriel means God is light, light of God or God’s fire, because the archangel illuminates situations and gives prophetic information and warnings. archangel uriel For example – Uriel warned Noah of the coming flood, helped the prophet Ezra to interpret m stical predictions about the coming of the !essiah and brought "abbalah humanit . Uriel is also credited with having devoted humanit #nowledge of alchem – the abilit to transform base metals into precious as the abilit to manifest in the air. Interesting fact: There are cases when the archangel Uriel warned people against accidents or disasters. Uriel’s color is garnet red, ruby red and gold. His energy is extremely empowering. He is responsible for the creation of material structures. Uriel is considered the wisest angel. $t is something li#e the old sage to whom ou can turn if ou need some intellectual information, practical solutions and creative ideas. $nstead, ou went to the mountain sage, Uriel comes instantl to ou. %owever, Uriel &s personalit is not so pronounced upon arrival, such as !ichael's. (ou need not even realize that Uriel has come to answer our prayers until ou notice that in our mind found a great new idea. )erhaps because of its association with Noah and his close relationship with such elements of weather, such as thunder and lightning, Uriel is considered an archangel who helps with earth*uakes, floods, fires, hurricanes, tornadoes, natural disasters and changes on the planet. To avert such events or remed damage, tr to call Uriel. -

Angels: God's Mysterious Messengers

TEACHINGS BY RABBI YECHIEL ECKSTEIN ANGELS INTRODUCTION BY YAEL ECKSTEIN TEN BIBLICAL LESSONS ON GOD’S MYSTERIOUS MESSENGERS For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways . — PSALM 91:11 Do you believe in angels? You should! The Bible is filled with story after story of encounters with these supernatural creatures who carry out God’s bidding. Clearly, God wants us to know about these mysterious messengers who He has sent to protect, encourage, guide, and assist us. Discover more about the role angels play in our daily lives through the encounters that people of the Bible have had with these otherworldly beings. The more we know about angels, the more confident we can be ANGELS in facing the challenges of our lives, knowing we are never alone. RABBI YECHIEL ECKSTEIN TEN BIBLICAL LESSONS In 1983, Rabbi Eckstein founded the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews (The Fellowship), devoting his life to building bridges of understanding between Christians and Jews and cultivating broad support for the state of Israel. Under ON GOD’S MYSTERIOUS his leadership, The Fellowship now raises over $125 million annually, making it the largest Christian-supported humanitarian nonprofit working in Israel today. MESSENGERS Rabbi Eckstein is the author of 10 highly acclaimed books, including How Firm a Foundation: A Gift of Jewish Wisdom for Christians and Jews, and The One Year® Holy Land Moments Devotional. His daily radio program, Holy Land Moments (Momentos en Tierra Santa), is now heard in English and Spanish on more than 1,500 stations on five continents, reaching more than 9.1 million listeners weekly. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 01 “What would Jesus Play?” - Actor-Centered Perspectives on Gaming and Gamers (In Lieu of an Introduction) Simone Heidbrink, Tobias Knoll & Jan Wysocki 17 Nephilim: Children of Lilith - The Place of Man in the Ontological and Cosmological Dualism of the Diablo, Darksiders and Devil May Cry Game Series Frank G. Bosman & Marcel Poorthuis 41 Living the Phantasm of Demediation - The Priest Kings and the Technology Prohibition in the Gorean Role-Playing Games Christophe Duret 61 “Venturing into the Unknown”(?) - Method(olog)ical Reflections on Religion and Digital Games, Gamers and Gaming Simone Heidbrink, Tobias Knoll & Jan Wysocki 85 Simulating the Apocalypse - Theology and Structure of the Left Behind Games Stephen Jacobs 107 The Politics of Pokemon – Socialized Gaming, Religious Themes and the Construction of Communal Narratives Marley-Vincent Lindsey 139 A Digital Devil’s Saga – Representation(s) of the Demon in Recent Videogames Jonathon O’Donnell 161 Prophecy, Pre-destination, and Free-form Gameplay - The Nerevarine Prophecy in Bethesda’s Morrowind Angus Slater Online – Heidelberg Journal for Religions on the Internet Volume 7 (2015) Religion in Digital Games Reloaded http://online.uni-hd.de Conference Papers: “Playing God” - On God & Game 185 Introduction: “Playing God” - On God & Game Frank G. Bosman 190 Beyond Belief - Playing with Pagan Spirituality in World of Warcraft Stef Aupers & Julian Schaap 207 “Are Those the Only Two Solutions?” - Dealing with Choice, Agency and Religion in Digital Games Tobias Knoll 227 -

What Is a Sacramental Person?

What is a Sacramental Person? We are a sacramental people because the Sacraments are, in truth, our lifeline to God. When we receive and celebrate the Church’s Sacraments, we really encounter the Church that Jesus founded. When we encounter the Church he founded, we really encounter Jesus Himself. And when we encounter Jesus, we really encounter the God who made us and loved us first. Our Archangels are Sacramental People: WHY? Gabriel Raphael Michael Uriel What is an archangel? Archangels are the highest degree of the angelic realm, and there are only four : They are the chief angels, and they are Michael, Gabriel, Raphael and Uriel. Each of the four archangels has a specific mission as well. The feast day of the archangels Gabriel, Michael and Raphael is September 29th The feast day of the archangel Uriel is July 28th Michael Name means “who is like God,” is the great warrior, the defender of the good and protector . In his icons, he holds a balance that weighs people’s deeds on Judgement Day, as well as a sword. Often he is represented defeating a dragon. He is the Leader of the Army of Heaven In Hebrew the name of the Archangel Michael means “The one who is like God”. Michael is the one who gives patience and happiness. The first Angel created by God, Michael is the leader of all the charge of protection, courage, strength, truth and integrity. Michael protects us physically, emotionally and psychically. He appears in scripture, and in art, sword in hand. Michael inspires those who struggle in loneliness and he is always ready to give a helping hand to the one in trouble or suffering. -

Angels, a Messenger by Any Other Name in the Judeo-Christian and Islamic Traditions

Angels, a Messenger by Any Other Name in the Judeo-Christian and Islamic Traditions Angels, a Messenger by Any Other Name in the Judeo-Christian and Islamic Traditions Edited by John T. Greene 2016 Proceedings Volume of the Seminar in Biblical Characters in Three Traditions and in Literature Angels, a Messenger by Any Other Name in the Judeo-Christian and Islamic Traditions Edited by John T. Greene This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by John T. Greene and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0844-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0844-6 As Always, in Memory of Misha And for Kamryn, a Prolific Writer of Books TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations ............................................................................................. ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Prolegomena: Angels and Some of their Various Roles in the Literature from Ancient Israel, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and in Literature John T. Greene Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

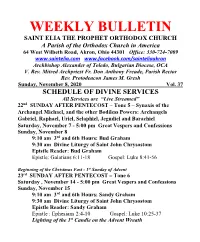

Weekly Bulletin

WEEKLY BULLETIN SAINT ELIA THE PROPHET ORTHODOX CHURCH A Parish of the Orthodox Church in America 64 West Wilbeth Road, Akron, Ohio 44301 Office: 330-724-7009 www.saintelia.com www.facebook.com/sainteliaakron Archbishop Alexander of Toledo, Bulgarian Diocese, OCA V. Rev. Mitred Archpriest Fr. Don Anthony Freude, Parish Rector Rev. Protodeacon James M. Gresh Sunday, November 8, 2020 Vol. 37 SCHEDULE OF DIVINE SERVICES All Services are “Live Streamed” 22nd SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST – Tone 5 – Synaxis of the Archangel Michael, and the other Bodiless Powers: Archangels Gabriel, Raphael, Uriel, Selaphiel, Jegudiel and Barachiel Saturday, November 7 - 5:00 pm Great Vespers and Confessions Sunday, November 8 9:10 am 3rd and 6th Hours: Bud Graham 9:30 am Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom Epistle Reader: Bud Graham Epistle: Galatians 6:11-18 Gospel: Luke 8:41-56 Beginning of the Christmas Fast - 1st Sunday of Advent 23rd SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST – Tone 6 Saturday , November 14 - 5:00 pm Great Vespers and Confessions Sunday, November 15 9:10 am 3rd and 6th Hours: Sandy Graham 9:30 am Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom Epistle Reader: Sandy Graham Epistle : Ephesians 2:4-10 Gospel: Luke 10:25-37 Lighting of the 1st Candle on the Advent Wreath GENERAL PARISH MEETING TODAY Today, Sunday, November 8, 2020, a General Parish Meeting will be held to elect the 2021 Parish Council, subject to the approval of he Archbishop. The following parishioners have been nominated: Subdeacon Terrence Bilas, Veronica Bilas, John Bohush IV, John Cheese, Tony Dodovich Reader Aaron Gray, Sarah Niglio, Tyler McKelvey, Joshua Wherley and Mary Marcin as COCA Representative PARISH STEWARDSHIP Your maintaining of your financial stewardship to St. -

{DOWNLOAD} Angel in Chains: the Fallen Ebook Free Download

ANGEL IN CHAINS: THE FALLEN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cynthia Eden | 352 pages | 01 Jan 2013 | Kensington Publishing | 9780758267634 | English | New York, United States Fallen angel - Wikipedia Jade Pierce. He stared at her hand. She wiggled her fingers at him. Slowly, Az lifted his own hand and caught those wiggling fingers. The door crashed in behind her. Because as the three black panthers—fully shifted panthers—leapt into the room, jumping over the broken door, Az grabbed Jade and threw her toward the couch. He should have known better than to let down his guard. Shifters and their damn acute senses. Only death. And with fast-paced action, readers are in for a wicked ride. Wilde Ways. Dark Sins. Lazarus Rising. Killer Instinct. Bad Things. Bite Series. Blood and Moonlight Series. LOST Series. Dark Obsession Series. Purgatory Series. Mine Series. Bound Series. Night Watch Series. Montlake - For Me Series. Harlequin Intrigue - Shadow Agents Series. Deadly Series. Phoenix Fire Series. The Fallen Series. Midnight Trilogy. Contemporary Anthologies. Paranormal Anthologies. Loved By Gods Series. Other Romantic Suspense. Other Paranormal. She took a step toward him. Though he knew well just how dangerous a touch could be. Holman Christian Standard Bible and He has kept, with eternal chains in darkness for the judgment of the great day, the angels who did not keep their own position but deserted their proper dwelling. International Standard Version He has also held in eternal chains those angels who did not keep their own position but abandoned their assigned place. They are held in deepest darkness for judgment on the great day. -

“Angel Chills” PREFACE Hope Angels Came About When My Struggle As

Hope Angel “Angel Chills” By Jeanne Leto PREFACE Hope Angels came about when my struggle as an intuitive and my belief in Christianity came to a colossal collision. Growing up sensitive - feeling, hearing, and seeing things beyond the physical realm - conflicted with the church’s teachings. I love God. I love Jesus Christ. I believe in each of them. One day, in conflict again with my abilities, I asked God what he wanted me to do. As plain as day, a voice said, “Give my people hope. Be a seer for me. Serve me and give hope.” Since that day, my reading sessions are in His hands. I do not seek to read at parties or force my work. Everything is now in God’s name, for His glory, and as I pray before each reading session, I call on God and His angels for guidance. Mostly, I pray for hope. God loves everyone, and everyone deserves hope. “Angel Chills” are simply what I get when I am feeling truth or when I am physically touched by angels. Hence, Hope Angels and Angel Chills. This book will teach you how to access God’s faithful angels. We were created by God for a purpose and so were His angels. Angels are appointed to serve, heal, protect, and guide. Each angel that serves God is waiting to help. I’ve been blessed to have experienced all three angelic realms including the highest order-- the seraphims! 1 Edited 02/19/2019 I invite you to enjoy the true experiences I’ve had as much as I did, and may you get “Angel Chills”.