Andrew Crocker Sees the Paintings Working Effectively on at Least Four Levels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STUDY GUIDE by Marguerite O’Hara, Jonathan Jones and Amanda Peacock

A personal journey into the world of Aboriginal art A STUDY GUIDE by MArguerite o’hArA, jonAthAn jones And amandA PeAcock http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘Art for me is a way for our people to share stories and allow a wider community to understand our history and us as a people.’ SCREEN EDUCATION – Hetti Perkins Front cover: (top) Detail From GinGer riley munDuwalawala, Ngak Ngak aNd the RuiNed City, 1998, synthetic polyer paint on canvas, 193 x 249.3cm, art Gallery oF new south wales. © GinGer riley munDuwalawala, courtesy alcaston Gallery; (Bottom) Kintore ranGe, 2009, warwicK thornton; (inset) hetti perKins, 2010, susie haGon this paGe: (top) Detail From naata nunGurrayi, uNtitled, 1999, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 2 122 x 151 cm, mollie GowinG acquisition FunD For contemporary aBoriGinal art 2000, art Gallery oF new south wales. © naata nunGurrayi, aBoriGinal artists aGency ltD; (centre) nGutjul, 2009, hiBiscus Films; (Bottom) ivy pareroultja, rrutjumpa (mt sonDer), 2009, hiBiscus Films Introduction GulumBu yunupinGu, yirrKala, 2009, hiBiscus Films DVD anD WEbsitE short films – five for each of the three episodes – have been art + soul is a groundbreaking three-part television series produced. These webisodes, which explore a selection of exploring the range and diversity of Aboriginal and Torres the artists and their work in more detail, will be available on Strait Islander art and culture. Written and presented by the art + soul website <http://www.abc.net.au/arts/art Hetti Perkins, senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait andsoul>. Islander art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and directed by Warwick Thornton, award-winning director of art + soul is an absolutely compelling series. -

Outstations Through Art: Acrylic Painting, Self‑Determination and the History of the Homelands Movement in the Pintupi‑Ngaanyatjarra Lands Peter Thorley1

8 Outstations through art: Acrylic painting, self-determination and the history of the homelands movement in the Pintupi-Ngaanyatjarra Lands Peter Thorley1 Australia in the 1970s saw sweeping changes in Indigenous policy. In its first year of what was to become a famously short term in office, the Whitlam Government began to undertake a range of initiatives to implement its new policy agenda, which became known as ‘self-determination’. The broad aim of the policy was to allow Indigenous Australians to exercise greater choice over their lives. One of the new measures was the decentralisation of government-run settlements in favour of smaller, less aggregated Indigenous-run communities or outstations. Under the previous policy of ‘assimilation’, living arrangements in government settlements in the Northern Territory were strictly managed 1 I would like to acknowledge the people of the communities of Kintore, Kiwirrkura and Warakurna for their assistance and guidance. I am especially grateful to Monica Nangala Robinson and Irene Nangala, with whom I have worked closely over a number of years and who provided insights and helped facilitate consultations. I have particularly enjoyed the camaraderie of my fellow researchers Fred Myers and Pip Deveson since we began working on an edited version of Ian Dunlop’s 1974 Yayayi footage for the National Museum of Australia’s Papunya Painting exhibition in 2007. Staff of Papunya Tula Artists, Warakurna Artists, Warlungurru School and the Western Desert Nganampa Walytja Palyantjaku Tutaku (Purple House) have been welcoming and have given generously of their time and resources. This chapter has benefited from discussion with Bob Edwards, Vivien Johnson and Kate Khan. -

THE DEALER IS the DEVIL at News Aboriginal Art Directory. View Information About the DEALER IS the DEVIL

2014 » 02 » THE DEALER IS THE DEVIL Follow 4,786 followers The eye-catching cover for Adrian Newstead's book - the young dealer with Abie Jangala in Lajamanu Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 13.02.14 Author: Jeremy Eccles News source: Review Adrian Newstead is probably uniquely qualified to write a history of that contentious business, the market for Australian Aboriginal art. He may once have planned to be an agricultural scientist, but then he mutated into a craft shop owner, Aboriginal art and craft dealer, art auctioneer, writer, marketer, promoter and finally Indigenous art politician – his views sought frequently by the media. He's been around the scene since 1981 and says he held his first Tiwi craft exhibition at the gloriously named Coo-ee Emporium in 1982. He's met and argued with most of the players since then, having particularly strong relations with the Tiwi Islands, Lajamanu and one of the few inspiring Southern Aboriginal leaders, Guboo Ted Thomas from the Yuin lands south of Sydney. His heart is in the right place. And now he's found time over the past 7 years to write a 500 page tome with an alluring cover that introduces the writer as a young Indiana Jones blasting his way through deserts and forests to reach the Holy Grail of Indigenous culture as Warlpiri master Abie Jangala illuminates a canvas/story with his eloquent finger – just as the increasingly mythical Geoffrey Bardon (much to my surprise) is quoted as revealing, “Aboriginal art is derived more from touch than sight”, he's quoted as saying, “coming as it does from fingers making marks in the sand”. -

2010.06 P49-52 A&C.Indd

ARTS+CULTURE SNAPSHOTS ART Stay up! It’s too hot to sleep and galleries and museums around town are staging White Nights. Check out the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC); Beijing Center for the Arts; the Beijing World, Today Art and CAFA Art Museums, UCCA and Three Shadows Photography Art Centre after the sun goes down. Ask at the latter for details of when and how. Meanwhile, Australia opens their Year of Culture in China with a bang: Papunya Tula at NAMOC (see p50) and a positively Spring-Festival- Gala-like array of talent at the NCPA on June 10. But wait! No sign of Kylie! www.imagineaustralia.net CINEMA The Fourth Beijing International Movie Festival (Jun 7-30) will be presenting a dizzying spectacle of independent films and film- makers from around the globe. It’s an Olympiad of film: Knowledge is the Beginning from Israel/Palestine (Jun 7, 26), Silent Shame from Japan (Jun 10), Die Entebehrlichen from Germany (Jun 11), not to mention a series of Irish film shorts (Jun 9). On the local scene, Channel Zero will screen a documentary titled 65 Red Roses about a young woman’s struggle with cystic fibrosis (Jun 15). As far as Hollywood output, Meg Ryan and Antonio Banderas couple up in My Mom’s New Boyfriend – a pairing so bizarre it may just need to be viewed on pirated DVD. IN PRINT QIU ZHEN'S "SATAN'S WEDDING" On June 15, Deborah Fallows XXXXXXXX visits The Bookworm to promote her second book, Dreaming in Chinese. Fallows, who has a Ph.D. -

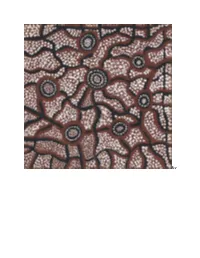

"Ice Dreaming" by Charlie Tjaruru Tjungarrayi by Abigail Connelly

Ice Dreaming, c. 1971 1996.0002.006 Charlie Tjaruru Tjungurrayi (1925-99) Pintupi language group, Kintore ranges Synthetic polymer on Masonite Written by Abigail Connelly In this painting, seven concentric circles are connected by curved black lines, some of which are outlined with a layer of red paint on one or both sides. Clusters of white dots adorn the background of the painting. The artist began with a layer of red paint as a base, followed by black, white, and then another layer of red. The earthy tones illustrated in this work are also represented in a majority of other Western Desert works from this period. The dawn of the Papunya Tula Art Movement was centered around a group of male artists, guided by Geoffrey Bardon. Bardon commissioned a variety of pieces, including at least five known works titled Ice Dreaming painted by Charlie Tjaruru. This is the first Ice Dreaming he painted and is the 82nd painting in the artist’s collective portfolio. John W. Kluge purchased this work from Museum Art International in 1996 and donated the work to the University of Virginia in 1997. Upon close inspection, this work has been attributed to Charlie Tjaruru Tjungurrayi (1925-99), whose name is also commonly spelled as Taruru, Tarawa, Wadama and Watuma. Tjaruru was born at Tjitururrnga, near Kintore in the Northern Territory, to parents Nuulyngu Tjapaltjarri and Karntintjungulnyu Nakamarra. His family was among some of the first people to move to the Haasts Bluff area, an area that housed a prominent Lutheran ration station run by missionaries. Charlie Tjaruru was given the name “Charlie” by Dr. -

Aboriginal Australian Cowboys and the Art of Appropriation Darren Jorgensen

Aboriginal Australian Cowboys and the Art of Appropriation Darren Jorgensen IN AMERICA, THE IMAGE OF THE COWBOY configures the ideals of courage, freedom, equality, and individualism.1 As close readers of the genre of the Western have argued, the cowboy fulfills a mythical role in American popular culture, as he stands between the so-called settlement of the country and its wilderness, between an idea of civilization and the depiction of savage Indians. The Western vaulted the cowboy to iconic status, as stage shows, novels, and films encoded his virtues in narratives set on the North American frontier of the nineteenth century. He became a figure of the popular national imagination just after this frontier had been conquered.2 From the beginning, the fictional cowboy was a character who played upon the nation’s idea of itself and its history. He came to assume the status of national myth and informed America’s economic, political, and social landscape over the course of the twentieth century.3 Yet this is only one na- tion’s history of the cowboy. As America became one of the largest exporters of culture on the planet, it exported its Western imagery, genre films, and novels. These cowboys were trans- formed in the hands of other cultural producers in other countries. From East German Indi- anerfilme to Italian spaghetti Westerns and Mexican films about caudillos (military leaders), the Darren Jorgensen is an associate professor in the School of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts at the University of Western Australia. He researches and publishes in the area of Australian art, as well as on contemporary art, critical theory, and science fiction. -

Art Aborigène Australie Samedi 14 Juin 2014 À - 16H30

Art Aborigène Australie Samedi 14 juin 2014 à - 16h30 Responsable de la vente : Nathalie Mangeot Commissaire-Priseur Expositions publiques [email protected] Tel : + 33 (0) 1 47 27 11 69 Vendredi 13 juin 2014 de 10h30 à 20h00 Port : + 33 (0) 6 34 05 27 59 Samedi 14 juin 2013 de 10h30 à 15h00 Expert : Marc Yvonnou Conférence le vendredi 13 juin à 18h00 Tel : + 33 (0)6 50 99 30 31 en Salle VV En partenariat avec Collection de M. M., Australie Collection S.P., Belgique ; Collection C.J., Belgique Suite de la Collection Anne de WALL, co-fondatrice du AAMU (Utrecht, Hollande) Et à divers collectionneurs Australiens et Français « L’art aborigène : différentes régions, différents styles » : Conférence sur les mouvements dans l’Art Aborigène donnée par Marc YVONNOU le vendredi 13 juin 2014 à 18h00 en Salle VV 1 • 2 • 3 • Samsan Japaljarri Martin Shorty Robertson Jangala Judy Watson Napangardi Sans titre (circa 1930 - ) Sans titre, 2004 Acrylique sur toile- 123 x 46 cm Ngapa Jukurrpu, 2006 Acrylique sur toile - 122 x 30 cm Groupe Warlpiri – Yuendumu – Acrylique sur toile - 123 x 46 cm Groupe Warlpiri – Yuendumu – Désert Central Désert Central Groupe Warlpiri - Désert Central Provenance : Collection privée, Mr. M., Australie Provenance : Collection particulière S.P., Belgique Provenance : Collection privée, Mr. M., Australie 1 500 / 2 000 € 500 / 700 € 1 800 / 2 000 € 5 • Lynette Granites Nampijinpa Sans titre, 1992 Acrylique sur toile - 117 x 72 cm Warlpiri - Yuendumu – Désert Central Provenance : Collection privée, Mr M., Australie 500 / 700 € 4 • 6 • Kenny Williams Tjampitjinpa Rosie Nangala Fleming Sans titre Sans titre Acrylique sur toile – 70 x 95 cm Acrylique sur toile - 61 x 30 cm Ethnie Pintupi – Désert Occidental Groupe Warlipri – Yuendumu – Désert 1 500 / 2 000 € Central Provenance : Collection privée, Mr. -

A Study Guide by Atom, Jonathan Jones and Amanda Peacock

A personal journey into the world of Aboriginal art A STUDY GUIDE BY ATOM, JONATHAN JONES AND AMANDA PEACOCK http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘Art for me is a way for our people to share stories and allow a wider community to understand our history and us as a people.’ SCREEN EDUCATION – Hetti Perkins FRONT COVER: (TOP) DETAIL FROM GINGER RILEY MUNDUWALAWALA, NGAK NGAK AND THE RUINED CITY, 1998, SYNTHETIC POLYER PAINT ON CANVAS, 193 X 249.3CM, ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES. © GINGER RILEY MUNDUWALAWALA, COURTESY ALCASTON GALLERY; (BOTTOM) KINTORE RANGE, 2009, WARWICK THORNTON; (INSET) HETTI PERKINS, 2010, SUSIE HAGON THIS PAGE: (TOP) DETAIL FROM NAATA NUNGURRAYI, UNTITLED, 1999, SYNTHETIC POLYMER PAINT ON CANVAS, 2 122 X 151 CM, MOLLIE GOWING ACQUISITION FUND FOR CONTEMPORARY ABORIGINAL ART 2000, ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES. © NAATA NUNGURRAYI, ABORIGINAL ARTISTS AGENCY LTD; (CENTRE) NGUTJUL, 2009, HIBISCUS FILMS; (BOTTOM) IVY PAREROULTJA, RRUTJUMPA (MT SONDER), 2009, HIBISCUS FILMS 5Z`^[PaO`U[Z GULUMBU YUNUPINGU, YIRRKALA, 2009, HIBISCUS FILMS DVD AND WEBSITE short films – five for each of the three episodes – have been art + soul is a groundbreaking three-part television series produced. These webisodes, which explore a selection of exploring the range and diversity of Aboriginal and Torres the artists and their work in more detail, will be available on Strait Islander art and culture. Written and presented by the art + soul website <http://www.abc.net.au/arts/art Hetti Perkins, senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait andsoul>. Islander art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and directed by Warwick Thornton, award-winning director of art + soul is an absolutely compelling series. -

Art Aborigène, Artistes Du Papunya Tula 29 Aout – 28 Septembre 2008

GALERIE PIERRICK TOUCHEFEU ________________________________________________ Communiqué de presse : Art Aborigène, artistes du Papunya Tula 29 Aout – 28 Septembre 2008 Considérée comme l’une des plus vieilles au monde, la civilisation aborigène sera une nouvelle fois à l’honneur à la Pierrick Touchefeu (Sceaux, 92) du 29 Aout au 28 Septembre 2008. Cette exposition montée en collaboration avec Mary Durack présentera des artistes parmi les plus emblématiques de l’art aborigène dont notamment Ningura NAPURRULA présent dans de nombreuses collections à travers le monde dont celle du Musée du Quai Branly à Paris et du Muséum de Lyon. Cette exposition présentera principalement des artistes originaires du Papunya Tula, lieu de naissance de la peinture aborigène contemporaine. Artistes présentés : Ningura Napurrula , Walangkura Napanangka, Elizabeth Marks, Lindsay Corby Tjapaltjarri , Frank Ward Tjupurrula, Tjunkiya Napaltjarri, Pansy Napangati, Kawayi Nampitjinpa Ci-dessus : Walangkura Napanangka (Uta Uta's widow) (91 x 46cm) GALERIE PIERRICK TOUCHEFEU ______________________________________ __________ Une civilisation vieille de 40 000 ans…ou plus ? Les chercheurs se sont longtemps accordés pour dater l’aube des traces humaines en Australie, sous forme de gravures et de peintures rupestres, à 40 000 ans. Soit près de trois fois plus que celles de Lascaux. Cependant, dès 1990, l’application de procédés de thermoluminescence a permis de reculer ces origines à…70 000 ans ! A l’arrivée des colonisateurs, il y aurait eu entre 600 et 700 tribus et dialectes différents, se partageant plus de 200 langues, dont une cinquantaine et douze groupes linguistiques majeurs subsistent de nos jours. Au sein de ces ethnies, ou groupe linguistique, la vie est organisée en clans, eux-mêmes de modeste dimension. -

Exhibiting Western Desert Aboriginal Painting in Australia's Public Galleries

Exhibiting Western Desert Aboriginal painting in Australia’s public galleries: an institutional analysis, 1981-2002 Jim Berryman Introduction Contemporary Aboriginal art, and the Western Desert painting movement in particular, now occupies a central position in the story of Australian art history. However, despite this recognition, Western Desert painting was slow to receive widespread critical and art-historical attention in the Australian art institutional setting. Eluding standard systems of art-historical classification, Australia’s public galleries struggled to situate Aboriginal acrylic painting within the narrative formations of Australian and international art practice. This paper charts the exhibition history of the movement, commencing with Papunya’s first appearance at a contemporary art event in 1981 until the movement’s institutional commemoration some two decades later. An analysis of catalogues from key exhibitions reveals three common strategies used by curators to interpret this new visual culture. Based on art-historical and anthropological discursive formations, these interpretative frameworks are called the aesthetic, ethnographic and ownership discourses. This investigation concentrates on the activities of Australia’s public galleries.1 As the traditional guardians of artistic standards, these institutions occupy positions of authority in the Australian art world. Comparative interpretations: aesthetic, ethnographic and ownership It is beyond the scope of this paper to explain the circumstances that gave rise to the -

Art of the Desert’

DEPARTMENT OF NEWS MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS www.fowler.ucla.edu Box 951549 Los Angeles, California 90095-1549 TEL 310.825.4288 FAX 310.206.7007 Stacey Ravel Abarbanel, [email protected] For Immediate Use 310/825-4288 March 10, 2009 Two Fowler Exhibitions Showcase Australia’s ‘Art of the Desert’ Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya and Innovations in Western Desert Painting, 1972–1999: Selections from The Kelton Foundation on display May 3–August 2, 2009 In 1971–1972 in the tiny settlement of Papunya, a group of Australian Aboriginal men began transferring their sacred ceremonial designs to pieces of masonite board. Since this crucial transformative period, Australian Aboriginal art has become an international phenomenon, widely exhibited and acquired by museums, galleries and collectors. The Fowler Museum will present two exhibitions from May 3–Aug 2, 2009— Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya and Innovations in Western Desert Painting, 1972-1999: Selections from The Kelton Foundation— which tell this remarkable story, from its inception in the early 70s to the profound changes reflected in works made by Aboriginal artists over the following two decades. Icons of the Desert In 1971, at Papunya, a government-established Aboriginal relief camp in the Central Australian desert, Sydney-based schoolteacher Geoffrey Bardon provided a group of ranking Aboriginal men with the tools and the encouragement to paint. The resulting works became the first paintings ever to systematically transfer the imagery of their culture to modern portable surfaces. The designs from which these are drawn are thousands of years old but still in regular use today; they appear in body painting for religious ceremonies and in the temporary ground-paintings of Pintupi and Warlpiri ceremonial sites. -

Jason Gibson and John Kean, ‘New Possum Found!’ Photographic Influences on Anmatyerr Art

Jason Gibson and John Kean, ‘New Possum Found!’ Photographic influences on Anmatyerr Art JASON GIBSON AND JOHN KEAN ‘New Possum Found!’ Photographic Influences on Anmatyerr Art ABSTRACT Despite extensive and at times contested retellings of the origins of Papunya Tula painting, few authors have identified the extent to which intercultural influences affected the work of the founding artists, preferring instead to interpret the emergence of contemporary Aboriginal art, at a remote settlement in Central Australia, as a marker of Indigenous cultural autonomy and resistance. A recently unearthed painting by the Anmatyerr artist Clifford Possum challenges this interpretation and suggests that the desert art movement arose from a more complex social milieu than has previously been acknowledged.1 As one of the earliest and most unusual paintings by a major Australian artist, the ‘new Possum’ is of undeniable significance. Our analysis of this work reveals that it is, in large part, derived from photographs published in a well-known anthropological classic. An examination of the painting and its sources will begin to build a picture of early influences on Anmatyerr art and the intriguing intercultural context in which the ‘new Possum’ and related works were created. Introduction ‘Possum’ is an emotive noun in Australian vernacular. Dame Edna Everage refers to her fans as ‘Possums’, while gardeners in leafy suburbs curse ‘bloody possums’ nightly as the insufferable marsupials thump on garage roofs, growl, fight and fornicate, before systematically stripping new shoots from exotic shrubs. Next to kangaroos and koalas, possums are probably the most widely known of our native animals. They are a paradoxical component of Australia’s endangered wildlife, thriving in the midst of urban expansion in the eastern states, and yet now almost completely absent from the continent’s arid heart.