Exhibition Catalogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corroboree Moderne

Corrected draft May 2004 CORROBOREE MODERNE ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Dressed in a brown wool bodystocking specially made by Jantzen and brown face paint, an American dancer, Beth Dean played the young boy initiate in the ballet CORROBOREE at a Gala performance before Queen Elizabeth 11 and Prince Phillip on Feb 4 1954 . “On stage she seems to exude some of the primitive passion of the savage whose rites she presents” (1a) “If appropriations do have a general character, it is surely that of unstable duality. In some proportion, they always combine taking and acknowledgment, appropriation and homage, a critique of colonial exclusions, and collusion in imbalanced exchange. What the problem demands is therefore not an endorsement or rejection of primitivism in principle, but an exploration of how particular works were motivated and assessed.” (1) CORROBOREE "announced its modernity as loudly as its Australian origins…all around the world" (2) 1: (BE ABORIGINAL !) (3) - DANCE A CORROBOREE! The 1950s in the Northern Territory represents simultaneously the high point of corroboree and its vanishing point. At the very moment one of the most significant cultural exchanges of the decade was registered in Australian Society at large, the term corroboree became increasingly so associated with kitsch and the inauthentic it was erased as a useful descriptor, only to be reclaimed almost fifty years later. Corroboree became the bastard notion par excellence imbued with “in- authenticity.” It was such a popularly known term, that it stood as a generic brand for anything dinky-di Australian. (4) Corroboree came to be read as code for tourist trash culture corrupted by white man influence. -

STUDY GUIDE by Marguerite O’Hara, Jonathan Jones and Amanda Peacock

A personal journey into the world of Aboriginal art A STUDY GUIDE by MArguerite o’hArA, jonAthAn jones And amandA PeAcock http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘Art for me is a way for our people to share stories and allow a wider community to understand our history and us as a people.’ SCREEN EDUCATION – Hetti Perkins Front cover: (top) Detail From GinGer riley munDuwalawala, Ngak Ngak aNd the RuiNed City, 1998, synthetic polyer paint on canvas, 193 x 249.3cm, art Gallery oF new south wales. © GinGer riley munDuwalawala, courtesy alcaston Gallery; (Bottom) Kintore ranGe, 2009, warwicK thornton; (inset) hetti perKins, 2010, susie haGon this paGe: (top) Detail From naata nunGurrayi, uNtitled, 1999, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 2 122 x 151 cm, mollie GowinG acquisition FunD For contemporary aBoriGinal art 2000, art Gallery oF new south wales. © naata nunGurrayi, aBoriGinal artists aGency ltD; (centre) nGutjul, 2009, hiBiscus Films; (Bottom) ivy pareroultja, rrutjumpa (mt sonDer), 2009, hiBiscus Films Introduction GulumBu yunupinGu, yirrKala, 2009, hiBiscus Films DVD anD WEbsitE short films – five for each of the three episodes – have been art + soul is a groundbreaking three-part television series produced. These webisodes, which explore a selection of exploring the range and diversity of Aboriginal and Torres the artists and their work in more detail, will be available on Strait Islander art and culture. Written and presented by the art + soul website <http://www.abc.net.au/arts/art Hetti Perkins, senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait andsoul>. Islander art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and directed by Warwick Thornton, award-winning director of art + soul is an absolutely compelling series. -

Yukultji Napangati - Pintupi

YUKULTJI NAPANGATI - PINTUPI Represented by Utopia Art Sydney 983 Bourke St, Waterloo NSW 2017 Tel: 61 2 9319 6437 utopiaartsydney.com.au [email protected] Yukultji Napangati is a rising star of the Papunya Tula Artists. She first came to the notice of a wider audience through her inclusion in the 2005 Primavera exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia. She is renowned for her shimmering surfaces and subtle use of colour, however, as an artist, she continues to explore all possibilities. Born circa 1971 near Wilkinkarra (Lake Mackay), “Yukultji was still a young girl when her family group came out of the desert into Kiwirrkurra in 1984, making national headlines as the ‘last’ of the desert nomads to make ‘first contact’” (Vivien Johnson, 2008). Yukultji began painting for Papunya Tula Artists in 1996. Her work is included in significant public and private collections, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and the Hood Museum of Art, USA. Yukultji won the Wynne Prize at the AGNSW in 2018. Awards 2018 Winner ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of New South Wales 2013 Highly Commended ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of New South Wales 2012 Winner, ‘The Alice Prize’ 2011 Highly Commended, ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of New South Wales Solo Exhibitions 2020 Yukultji Napangati, Utopia Art Sydney, NSW 2019 Yukultji Napangati, Salon94, New York, USA 2014 Yukultji Napangati, Utopia Art Sydney, NSW Selected Group Exhibitions 2020 ‘Wynne Prize’, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney -

Indigenous Archives

INDIGENOUS ARCHIVES 3108 Indigenous Archives.indd 1 14/10/2016 3:37 PM 15 ANACHRONIC ARCHIVE: TURNING THE TIME OF THE IMAGE IN THE ABORIGINAL AVANT-GARDE Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll Figure 15.1: Daniel Boyd, Untitled TI3, 2015, 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, All the World’s Futures. Photo by Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: la Biennale di Venezia. Daniel Boyd’s Untitled T13 (2015) is not an Aboriginal acrylic dot painting but dots of archival glue placed to match the pixel-like 3108 Indigenous Archives.indd 342 14/10/2016 3:38 PM Anachronic Archive form of a reproduction from a colonial photographic archive. Archival glue is a hard, wax-like material that forms into lumps – the artist compares them to lenses – rather than the smooth two- dimensional dot of acrylic paint. As material evidence of racist photography, Boyd’s paintings in glue at the 2015 Venice Biennale exhibition physicalised the leitmotiv of archives. In Boyd’s Untitled T13 the representation of the Marshall Islands’ navigational charts is an analogy to the visual wayfinding of archival photographs. While not associated with a concrete institution, Boyd’s fake anachronic archive refers to institutional- ised racism – thus fitting the Biennale curator Okwui Enwezor’s curatorial interest in archival and documentary photography, which he argues was invented in apartheid South Africa.1 In the exhibition he curated in 2008, Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, Enwezor diagnosed an ‘archival fever’ that had afflicted the art of modernity since the invention of photography. The invention, he believed, had precipitated a seismic shift in how art and temporality were conceived, and that we still live in its wake. -

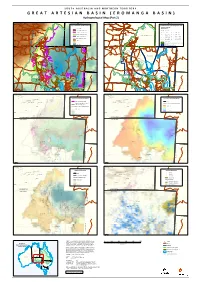

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Important Australian and Aboriginal

IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including The Hobbs Collection and The Croft Zemaitis Collection Wednesday 20 June 2018 Sydney INSIDE FRONT COVER IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including the Collection of the Late Michael Hobbs OAM the Collection of Bonita Croft and the Late Gene Zemaitis Wednesday 20 June 6:00pm NCJWA Hall, Sydney MELBOURNE VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION Tasma Terrace Online bidding will be available Merryn Schriever OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 6 Parliament Place, for the auction. For further Director PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE East Melbourne VIC 3002 information please visit: +61 (0) 414 846 493 mob IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS www.bonhams.com [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Friday 1 – Sunday 3 June CONDITION OF ANY LOT. 10am – 5pm All bidders are advised to Alex Clark INTENDING BIDDERS MUST read the important information Australian and International Art SATISFY THEMSELVES AS SYDNEY VIEWING on the following pages relating Specialist TO THE CONDITION OF ANY NCJWA Hall to bidding, payment, collection, +61 (0) 413 283 326 mob LOT AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 111 Queen Street and storage of any purchases. [email protected] 14 OF THE NOTICE TO Woollahra NSW 2025 BIDDERS CONTAINED AT THE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Francesca Cavazzini END OF THIS CATALOGUE. Friday 14 – Tuesday 19 June The United States Government Aboriginal and International Art 10am – 5pm has banned the import of ivory Art Specialist As a courtesy to intending into the USA. Lots containing +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob bidders, Bonhams will provide a SALE NUMBER ivory are indicated by the symbol francesca.cavazzini@bonhams. -

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent Reviewer Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (Cth) 1999 16 April 2020 HEAD OFFICE 27 Stuart Hwy, Alice Springs POST PO Box 3321 Alice Springs NT 0871 1 PHONE (08) 8951 6211 FAX (08) 8953 4343 WEB www.clc.org.au ABN 71979 619 0393 ALPARRA (08) 8956 9955 HARTS RANGE (08) 8956 9555 KALKARINGI (08) 8975 0885 MUTITJULU (08) 5956 2119 PAPUNYA (08) 8956 8658 TENNANT CREEK (08) 8962 2343 YUENDUMU (08) 8956 4118 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 3 2. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... 4 3. OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 5 4. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 5. MODERNISING CONSULTATION AND INPUT ......................................................... 7 5.1. Consultation processes ................................................................................................... 8 5.2. Consultation timing ........................................................................................................ 9 5.3. Permits to take or impact listed threatened species or communities ........................... 10 6. CULTURAL HERITAGE AND SITE PROTECTION .................................................. 11 7. BILATERAL -

Family News 67

Family News Edition 67 Lexi Ward from Aputula and story on pg4 © Waltja Tjutangku Palyapayi Aboriginal Corporation “ doing good work with families” Postal: PO Box 8274 Alice Springs NT 0871 Location: 3 Ghan Rd Alice Springs NT 0870 Ph: (08) 8953 4488 Fax: (08) 89534577 Website: www.waltja.org.au Waltja Chairperson 2020ngka ngarangu watjil, watjilpa, tjilura, tjiluru nganampa Waltja tjutaku. Ngurra tjutanya patirringu marrkunutjananya ngurrangka nyinanytjaku wiya tawunukutu ngalya yankutjaku. Tjananya watjanu wiya, ngaanyakuntjaku Waltja kutjupa tjutangku tjana patikutu nyinangi Waltjangku, katjangku, yuntalpanku, tjamuku nyaakuntja wiya. Ngurra purtjingka nyinapaiyi tjutanya, Kapumantaku marrkunu tjananya nyinantjaku ngurrangka Tjanaya watjil watjilpa, nyinangi wiya nganana yuntjurringnyi tawunukatu yankutjaku mangarriku, yultja mantjintjaku Waltjalu? Tjanampa yiyanangi yultja tjuta ngurra winkikutu. Tjana yunparringu ngurra winkinya mangarriku Walytjalu yiyanutjangka. Walytjalu yilta tjananya puntura alpamilaningi. Panya Sharijnlu watjanutjangka. Yanangi warrkana tjutanya ngurra tjutakutu. Youth worker, NDIS, culture anta governance tjuta warrkanarripanya Walytjaku kimiti tjutanyalatju tjungurrikula miitingingka wankangi 12 times Member tjutangku miitingingka wangkangi AGM miitingi. Panya minta kuyangkulampa yangatjunu. AGM miitingi ngaraku March-tjingka (2021-ngngka) Nganana yuntjurrinyi minmya tjutaku ngurra tjutaku. Yukarraku, Ulkumanuku, nganana yuntjurringanyi. Palyaya nyinama ngurrangka Walytja tjuta kunpurringamaya. Palya Nangala. 2020 was a hard year, a sad year for people. The remote communities were locked down and no visiting each other. No shopping in Alice Springs. Everyone was crying for warm clothes and food. Oh we were too busy at Waltja clothes and food everywhere! Sending to every community. The rest of the year we were working with Sharijn to do all the programs, help the workers to go bush. Youth work, NDIS, culture and governance work. -

The Debilitating Aftermath of 10 Years of NT Intervention

18 Land Rights News • Northern Edition July 2017 • www.nlc.org.au The debilitating aftermath of 10 years of NT Intervention Jon Altman* n the April issue of Land Rights News I This is of special concern to Indigenous I do this because the Intervention was Both communities were established by celebrated the 30th anniversary of the people in the Northern Territory if the heavily promoted as a major project of the Commonwealth in 1959 and 1957 progressive and supportive Blanchard Commonwealth’s constitutional territory improvement and modernisation. Who can respectively and were colloquially referred report Return to Country: the Aboriginal powers remain in place and if, as in 2007, forget Malcolm Brough’s heroic call to to as ‘the Jewel of the Centre’ and ‘the Homelands Movement in Australia. And racial discrimination laws can be suspended ‘Stabilise, Normalise and Exit’ remote NT Jewel of the North’: these were to be the I wondered what celebration or reproach at the whim of the government of the day. communities, the delivery of what can be two demonstration communities where the the 10th anniversary of the Northern thought of as a domestic ‘Marshall Plan’ to Welfare Branch was going to show to all Third are the views expressed by Territory National Emergency Response, demonstrate the developmental powers of how modernisation and development could Indigenous community leaders who are the Intervention that was militaristically the Australian government in a jurisdiction and should be delivered. also subjects of the Intervention, several launched with extraordinary media fanfare where owing to a quirk of the Australian whom I heard present views in two events In 1972 when policy shifted to self- on 21 June 2007 might elicit. -

Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2Pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia Tional in Fi Le Only - Over Art Fi Le

Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia tional in fi le only - over art fi le 5 Bonhams The Laverty Collection 6 7 Bonhams The Laverty Collection 1 2 Bonhams Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia Bonhams Viewing Specialist Enquiries Viewing & Sale 76 Paddington Street London Mark Fraser, Chairman Day Enquiries Paddington NSW 2021 Bonhams +61 (0) 430 098 802 mob +61 (0) 2 8412 2222 +61 (0) 2 8412 2222 101 New Bond Street [email protected] +61 (0) 2 9475 4110 fax +61 (0) 2 9475 4110 fax Thursday 14 February 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] Friday 15 February 9am to 4.30pm Greer Adams, Specialist in Press Enquiries www.bonhams.com/sydney Monday 18 February 9am to 4.30pm Charge, Aboriginal Art Gabriella Coslovich Tuesday 19 February 9am to 4.30pm +61 (0) 414 873 597 mob +61 (0) 425 838 283 Sale Number 21162 [email protected] New York Online bidding will be available Catalogue cost $45 Bonhams Francesca Cavazzini, Specialist for the auction. For futher 580 Madison Avenue in Charge, Aboriginal Art information please visit: Postage Saturday 2 March 12pm to 5pm +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob www.bonhams.com Australia: $16 Sunday 3 March 12pm to 5pm [email protected] New Zealand: $43 Monday 4 March 10am to 5pm All bidders should make Asia/Middle East/USA: $53 Tuesday 5 March 10am to 5pm Tim Klingender, themselves aware of the Rest of World: $78 Wednesday 6 March 10am to 5pm Senior Consultant important information on the +61 (0) 413 202 434 mob following pages relating Illustrations Melbourne [email protected] to bidding, payment, collection fortyfive downstairs Front cover: Lot 21 (detail) and storage of any purchases. -

3Rd Grade Art Docent Lesson

Grade 3 – Aboriginal Dot Painting Texture What do you see? Water Dreaming, 2014, Robertson Artistic Focus: Texture TEXTURE is an element of visual arts that portrays surface quality. • Actual texture is how something feels. • Visual texture is how something appears to feel. Today’s objective: 1. To practice dot painting as a way to create visual texture 2. To use alternative tools to paint WA State Visual Arts Standard Identify and explain how and where different cultures record and illustrate stories and history of life. (VA: Pr6.1.3) Water Dreaming, 2014, Robertson Shorty Jangala Robertson • Australia, Jila (Chilla Well) • 1925-2014 • Of the Warlpiri people. • Member of the Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd. • Painted “dreamings” of water, acacia, and local animals. • Finding water is critical to survival in the Australian Western Desert, so water is an important theme in Robertson’s paintings. • Used brushes, cotton swabs, or other alternative tools to paint on canvas, bark, or other hard surfaces. Papunya Tula Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd (proprietary company limited) is an artist cooperative formed in 1972 that is owned and operated by Aboriginal people from the Western Desert of Australia. The group is known for its innovative work with the Western Desert Art Movement, popularly referred to as "dot painting". The company operates today out of Alice Springs and is widely regarded as the premier purveyor of Aboriginal art in Central Australia. Artwork Ngapa Jukurrpa (Water Dreaming), 2006 Shorty Jangala Robertson Flood waters surge across the canvas. This painting is on display in the Seattle Art Museum. Artwork Ngapa Jukurrpa (Water Dreaming), early 2000’s Materials artist’s palette cotton swabs to apply the paint paper towels tempera paint in autumn forest orange construction paper with a colors, black & white leaf stenciled on it Examples of Today’s Project Before You Begin 1. -

Outstations Through Art: Acrylic Painting, Self‑Determination and the History of the Homelands Movement in the Pintupi‑Ngaanyatjarra Lands Peter Thorley1

8 Outstations through art: Acrylic painting, self-determination and the history of the homelands movement in the Pintupi-Ngaanyatjarra Lands Peter Thorley1 Australia in the 1970s saw sweeping changes in Indigenous policy. In its first year of what was to become a famously short term in office, the Whitlam Government began to undertake a range of initiatives to implement its new policy agenda, which became known as ‘self-determination’. The broad aim of the policy was to allow Indigenous Australians to exercise greater choice over their lives. One of the new measures was the decentralisation of government-run settlements in favour of smaller, less aggregated Indigenous-run communities or outstations. Under the previous policy of ‘assimilation’, living arrangements in government settlements in the Northern Territory were strictly managed 1 I would like to acknowledge the people of the communities of Kintore, Kiwirrkura and Warakurna for their assistance and guidance. I am especially grateful to Monica Nangala Robinson and Irene Nangala, with whom I have worked closely over a number of years and who provided insights and helped facilitate consultations. I have particularly enjoyed the camaraderie of my fellow researchers Fred Myers and Pip Deveson since we began working on an edited version of Ian Dunlop’s 1974 Yayayi footage for the National Museum of Australia’s Papunya Painting exhibition in 2007. Staff of Papunya Tula Artists, Warakurna Artists, Warlungurru School and the Western Desert Nganampa Walytja Palyantjaku Tutaku (Purple House) have been welcoming and have given generously of their time and resources. This chapter has benefited from discussion with Bob Edwards, Vivien Johnson and Kate Khan.