Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Space and Recreation Plan Town of Rockport

OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN TOWN OF ROCKPORT 2019 ®Maps produced by Peter Van Demark using Maptitude GIS software Final Approval 7 October 2020 Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Open Space and Recreation Committee: Lawrence Neal, Conservation Commission and Chair, Rob Claypool, Stephanie Cunningham, Tom Mikus, Rights of Way, Frederick H. “Ted” Tarr III, Peter Van Demark, Cartographer Open Space and Recreation Plan for the Town of Rockport 2019 - 2026 2 Open Space and Recreation Plan for the Town of Rockport 2019 - 2026 PROSPERITY FOLLOWS SERVICE PATHWAYS The Islanders had built along the shoreline leaving the center of the island almost virgin overgrown with trees and brush, an occasional open area here, a granite deposit there. Pathways cut through the terrain, offering a tourist hiker several choices. A new path is always an adventure. The first passage is more a reconnoiter concentrating on direction, orientation, markers and eventual destination. The second pass is leisurely and indulgent allowing time to appreciate the colors, odors, indigenous flora, local fauna, the special essence of the place. Approach a poem like a wooded path with secrets to impart, one reading will reveal her scheme, the second her heart. from Pathways by J.J. Coyle This plan is dedicated to Frederick H. “Ted” Tarr, III. Thank you for the pathways. Thank you for your service. 3 Open Space and Recreation Plan for the Town of Rockport 2019 - 2026 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................ -

OUR MISSION DCR’S Universal Access Program Is Dedicated to Providing Outdoor Recreation Opportunities in Massachusetts State Parks for Visitors of All Abilities

DCR UAP Program Schedule Summer/FallAccess News 2019Page 1 OUR MISSION DCR’s Universal Access Program is dedicated to providing outdoor recreation opportunities in Massachusetts State Parks for visitors of all abilities. Accessibility is achieved through site improvements, specialized adaptive recreation equipment, and accessible recreation programs. Pre-registration is required for all programs. To pre-register, contact the providing organization. Get into the activity sooner by bringing your release form filled out: mass.gov/dcr/universal-access/release Our structured programs feature adaptive equipment, professional staff, and instruction and support. Friends, family, and companions are welcome to take part in our programs alongside participants with disabilities. Visit our website to keep up-to-date with our activities! mass.gov/dcr/universal-access Donations welcome! DCR’s Conservation Trust and Urban Parks Trust Fund accepts contributions to support and enhance outdoor recreation in Massachusetts for people of all abilities. Your tax-deductible donation will help provide access to our parks. Ask us about matching funds! To learn more, visit: mass.gov/dcr/universal-access/donate Checks should be made out to The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, noting that the funds are for the Universal Access Program (UAP), and sent to: DCR’s Universal Access Program P.O. Box 484 Amherst, MA 01004 Access News Page 2 Hiking program that travels around the state! Take a gentle hike with Stavros Outdoor Access. Date Location Adaptive equipment and staff assistance provided. June 20 George’s Island, Bring a lunch and enjoy nature activities, Boston Harbor scavenger hunts, letterboxing, and more. June 27 Great Brook Farm State Park, Carlisle Cost: $3/person, $12/family, $25/group July 11 Walden Pond State Reservation, Concord July 18 Mt. -

Outdoor Recreation Recreation Outdoor Massachusetts the Wildlife

Photos by MassWildlife by Photos Photo © Kindra Clineff massvacation.com mass.gov/massgrown Office of Fishing & Boating Access * = Access to coastal waters A = General Access: Boats and trailer parking B = Fisherman Access: Smaller boats and trailers C = Cartop Access: Small boats, canoes, kayaks D = River Access: Canoes and kayaks Other Massachusetts Outdoor Information Outdoor Massachusetts Other E = Sportfishing Pier: Barrier free fishing area F = Shorefishing Area: Onshore fishing access mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/fba/ Western Massachusetts boundaries and access points. mass.gov/dfw/pond-maps points. access and boundaries BOAT ACCESS SITE TOWN SITE ACCESS then head outdoors with your friends and family! and friends your with outdoors head then publicly accessible ponds providing approximate depths, depths, approximate providing ponds accessible publicly ID# TYPE Conservation & Recreation websites. Make a plan and and plan a Make websites. Recreation & Conservation Ashmere Lake Hinsdale 202 B Pond Maps – Suitable for printing, this is a list of maps to to maps of list a is this printing, for Suitable – Maps Pond Benedict Pond Monterey 15 B Department of Fish & Game and the Department of of Department the and Game & Fish of Department Big Pond Otis 125 B properties and recreational activities, visit the the visit activities, recreational and properties customize and print maps. mass.gov/dfw/wildlife-lands maps. print and customize Center Pond Becket 147 C For interactive maps and information on other other on information and maps interactive For Cheshire Lake Cheshire 210 B displays all MassWildlife properties and allows you to to you allows and properties MassWildlife all displays Cheshire Lake-Farnams Causeway Cheshire 273 F Wildlife Lands Maps – The MassWildlife Lands Viewer Viewer Lands MassWildlife The – Maps Lands Wildlife Cranberry Pond West Stockbridge 233 C Commonwealth’s properties and recreation activities. -

Winthrop Town Manager's Weekly Blog

WINTHROP TOWN MANAGER’S WEEKLY BLOG June 15, 2017 Volume 2, Number 24 Manager’s Message from your Town Manager, Jim McKenna GRAND PARADE OF SAIL Saturday, June 17 | 9:00 AM – 3:00 PM The Grand Parade of Sail will highlight the day’s activities as vessels parade in flotillas from Broad Sound into the main channel of Boston Harbor turning at Charlestown, before proceeding to their assigned berthing areas. Public viewing of the parade will be spectacular from Castle Island, the Seaport District, the Boston Waterfront, East Boston, the North End and Charlestown. SPECTATOR AREAS ON DEER ISLAND SAIL BOSTON SHUTTLE TO YIRRELL BEACH ON SATURDAY, JUNE 17 The Town of Winthrop will be providing a free shuttle service for the Sail Boston events being held at Yirrell Beach on Saturday, June 17, 2017 from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM. All vessels taking part in the Parade of Sail will be staging off-shore in this area prior to making the turn at Deer Island and heading into the harbor. This shuttle will transport people from designated off-site parking areas to the Public Landing for access to Yirrell Beach. Signs for the off-site parking will be posted for this event and have been designated as the following: Veterans Road: Park/Golf Course side Winthrop Middle/High School Rear Lot Perimeter of the High School Tennis Courts Walden Street: Ingleside Park Side Larsen Rink Parking Lot Walden Street Parking Lot Cummings School Parking Lot on School Street Shuttle stops will be posted and are being provided in the following locations: Four stops along the length of Veterans Road The Cross Street side of the Middle/High School Walden Street The corner of Walden & Pauline Streets School Street (in the rear of the Cummings School) The Public Landing The shuttle route will begin and end at the Public Landing, and will run in a loop approximately every 20 minutes. -

Halibut Point State Park Self-Guided Walking Tour

elcome to Halibut Point, a 3. Dog Holes uniquely beautiful coastal The single round hole on the face of this piece of granite is granite from the quarry site to the wharf at nearby Folly Cove where the stone was loaded onto specially designed landscape. Looking seaward on called a dog hole. Large granite blocks typically had a dog E AN a clear day, the view stretches hole drilled into each end to hold the tips of giant hooks sloops that carried it to markets all over the hemisphere. C W called dogs that were suspended by cables and chains from a O from Crane Beach in Ipswich to Mount derrick. The loop of chain tightened the grasp of the dogs as C look 6. Splitting the Stone I Over Agamenticus in Maine and the Isles of the block of granite was lifted from the quarry. T nic In the early days of the granite industry on Cape Ann, N Sce Shoals off the coast of New Hampshire. granite was split by making holes with a flat chisel and A Once the block reached the surface, it was moved by oxen, L 7 horses or train to nearby sheds where men shaped it into then by driving flat wedges down into the holes. Some split T The park is managed for scenic, historic and paving blocks, curbing, building stone or ornamental pieces. stones can still be found around the park that show signs of A conservation purposes. It is administered Here at Halibut Point granite was transported directly to the these rectangular holes. -

DCR's 10Th Annual Park Serve Day Set

For Immediate Release - April 19, 2016 DCR’s 10th Annual Park Serve Day Set for Saturday, April 30, 2016 Public is Encouraged to Join Thousands of Volunteers at Statewide Park Clean- Up Events Boston- Tuesday, April 19, 2016- Today, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) has announced that the 10th annual Park Serve Day will be held on Saturday, April 30, 2016, and the agency encourages members of the public to participate in events held at local state parks and beaches. Park Serve Day is a statewide initiative dedicated to a day of volunteer service where the public partners with staff from the DCR to ready the Commonwealth’s parks and beaches for summer by assisting in cleaning coastlines, clearing trails, planting flowers, painting picnic tables, mowing, weeding, and picking up litter. “From planting flowers and trees to painting picnic tables and welcome signs, Park Serve Day is an incredible opportunity for state government to partner with the public in an effort to benefit us all,” said Governor Charlie Baker. “By working together, generations of people will truly benefit from this worthwhile event.” Park Serve Day improves natural, cultural, and recreational public spaces throughout Massachusetts through volunteerism at local events. The majority of events will take place between the hours of 8:00AM and 3:00PM, though hours may vary by location, and participants are encouraged to reach out to their local state parks to confirm event times. “Every year thousands of volunteers pitch in and participate in DCR’s annual Park Serve Day, and I’m so proud of their work and commitment at our state parks” said Lieutenant Governor Karyn Polito. -

Baker-Polito Administration Announces Temporary Closure of Certain State Conservation and Recreation Managed Facilities

E M E R G E N C Y A L E RT S Coronavirus Update SHOW ALERTS Mass.gov PRESS RELEASE Baker-Polito Administration Announces Temporary Closure of Certain State Conservation and Recreation Managed Facilities FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 3/13/2020 Department of Conservation & Recreation MEDIA CONTACT Olivia Dorrance, Press Secretary Phone (617) 626-4967 (tel:6176264967) Online [email protected] (mailto:[email protected]) BOSTON - Out of an abundance of caution due to the spread of COVID-19 in Massachusetts, the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) has announced the temporary closure of certain agency managed facilities effective Saturday, March 14, 2020 through Wednesday, April 1, 2020 at which time DCR will reassess circumstances. Additionally, during the temporary closure all associated events at these locations are cancelled. Importantly, all state parks and comfort stations across the Commonwealth remain open and available for the public to utilize. DCR reminds residents and visitors to avoid gathering in large groups, maintain social distancing, and practice healthy personal hygiene to stop the spread of the virus. The temproary closures of certain facilities is consistent with the State of Emergency declared (/news/governor-baker-declares-state-of-emergency-to-support-commonwealths-response-to-coronavirus) by Governor Baker on Tuesday, March 10, 2020 and guidance that conferences, seminars and other discretionary gatherings, scheduled and hosted by Executive Branch agencies involving external parties are to be held virtually or cancelled. Additionally, Governor Charlie Baker issued (/news/governor-baker-issues-order-limiting-large-gatherings-in-the-commonwealth) an emergency order prohibiting most gatherings of over 250 people to limit the spread of the COVID-19. -

MASTER HHT Facility Information

Department of Conservation and Recreation Healthy Heart Trails Location Information ADA Facility Name Name of Trail Surface Accessible Lenth of Trail Activity Level Starting Point Ashuwillticook Rail Trail Ashuwillticook Rail Trail Paved Yes 11 miles Easy Berkshire Mall Rd. Park at Lanesboro/Discover Berkshire Visitor Center-Depot St., Adams Beartown State Forest Benedict Pond Loop Trail Unpaved No 1.5 Miles Easy Boat Ramp Parking Area at Benedict Pond Beaver Brook Loop starting in main parking lot Partially Paved yes .75 Miles Easy Start at Main parking Lot Beaver Brook Reservation Beaver Brook Loop Partially Paved Yes .75 Miles Easy Begins at the main parking area on waverly Oaks Rd. in Waltham Belle Isle Marsh Reservation Belle Isle Meadow Loop Unpaved Yes 0.6 Miles Easy Start at the main parking lot off Bennington Street, East Boston Blackstone River & Canal HSP Blackstone Canal Towpath Trail Unpaved No 1 Mile Easy Tri River Health Center Parking Lot Borderland State Park Part of Pond Walk Unpaved No 1.5 Miles Easy Visitor's Center Bradley Palmer State Park Interpretive Trails #46 and #2 Unpaved No 1.2 Miles Easy Interpretive Trail #46 behind the Headquarters Building trail begins off main parking lot near visitor center Breakheart Reservation (fox run trail to Saugus River trail) Unpaved 1.4 Miles Moderate Breakheart Visitor Center Callahan State Park Backpacker/Acorn Trail Unpaved No 1.5 Miles Moderate Broad Meadow Parking Lot Castle Island Castle Island Loop Paved Yes .75 Miles Easy At the junction of the playground and main path Charles River Esplanade Esplanade Loop Paved Yes 1.5 Miles Easy Path begins at the Lee Pool Parking Lot Chestnut Hill Reservation Reservoir Loop Unpaved Yes 1.5 Miles Easy Start at the bulletin board on Beacon Street near the skating rink Chicopee Memorial State Park Loop Trail Paved Yes 2.4 Miles Easy Base of the Recreation Area Parking Lot Cochituate State Park Snake Brook Trail Unpaved Yes 1.5 Miles Moderate Rt 27 in Wayland. -

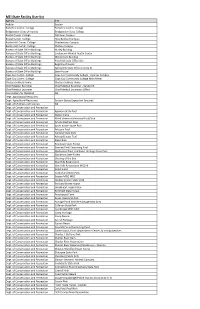

MEI State Facilities Inventory List.Xlsx

MEI State Facility User list Agency Site Auditor Boston Berkshire Comm. College Berkshire Comm. College Bridgewater State University Bridgewater State College Bristol Comm. College Fall River Campus Bristol Comm. College New Bedford Campus Bunker Hill Comm. College Charlestown Campus Bunker Hill Comm. College Chelsea Campus Bureau of State Office Buildings Hurley Building Bureau of State Office Buildings Lindemann Mental Health Center Bureau of State Office Buildings McCormack Building Bureau of State Office Buildings Pittsfield State Office Site Bureau of State Office Buildings Registry of Deeds Bureau of State Office Buildings Springfield State Office Liberty St Bureau of State Office Buildings State House Cape Cod Comm. College Cape Cod Community College ‐ Hyannis Campus Cape Cod Comm. College Cape Cod Community College Main Meter Chelsea Soldiers Home Chelsea Soldiers Home Chief Medical Examiner Chief Medical Examiner ‐ Sandwich Chief Medical Examiner Chief Medical Examiners Office Commission for the Blind NA Dept. Agricultural Resources Dept. Agricultural Resources Eastern States Exposition Grounds Dept. of Children and Families NA Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Agawam State Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Aleixo Arena Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Allied Veterans Memorial Pool/Rink Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Amelia Eairhart Dam Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ames Nowell State Park Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Artesani Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ashland State Park Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ashuwillticook Trail Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Bajko Rink Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Beartown State Forest Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Bennett Field Swimming Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Blackstone River and Canal Heritage State Park Dept. -

Open Space and Recreational Plan 2009-2016

Open Space and Recreation Plan for the Town of Rockport 2009 FINAL SUBMISSION Open Space and Recreation Committee Members Eric Hutchins, Watershed Protection Committee Christopher Lewis Donna Marshall-Higgins, Recreation Committee Lawrence Neal, Conservation Commission Marcia B. Siegel, Rights of Way Committee Mary Ruth Sole, Planning Board Peter Van Demark, Cartographer Maps produced by Peter Van Demark using Maptitude® GIS software Open Space and Recreation Plan for the Town of Rockport 2009-2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF MAPS .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Section 1 PLAN SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 4 Section 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 5 2A Statement of Purpose ........................................................................................................................... 5 2B Planning Process and Public Participation .......................................................................................... 6 Section 3 COMMUNITY SETTING ................................................................................................................... 8 3A Regional Context ................................................................................................................................ -

Essex Coastal Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan Appendices

Essex Coastal Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan Appendices prepared for Essex National Heritage Commission by Brown Walker Planners, Inc. Gates, Leighton & Associates, Inc. Jacobs Engineering Group, Inc. Wild Water International March 2011 The Essex Coastal Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan was funded by the Federal Highway Administration through the National Scenic Byway Program and by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Essex Coastal Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan Table of Contents Appendix 1: Byway Roadway Characteristics and Safety Analysis...........................................................1 Summary of Byway Roadway Characteristics............................................................................................. 1 Crash Summary........................................................................................................................................... 2 Appendix 2: Commuter Rail Stations along the Byway ...........................................................................1 Appendix 3: Description of the Byway Route by Community..................................................................1 Lynn ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Swampscott................................................................................................................................................ 1 Marblehead ............................................................................................................................................... -

This Listing of DCR Properties Is Meant to Supplement the Landscape Designations Map with Additional Information

This listing of DCR properties is meant to supplement the Landscape Designations map with additional information. It shows how many acres from each property are assigned to each landscape designation, but cannot detail which parts of each property are assigned to each designation – please see the maps for that information. The properties below are listed as named in DCR's GIS databases; GIS names may not match all names posted at facilities or known locally. The column labeled "ELU" identifies in which Ecological Land Unit the property belongs. Properties in the same ELU share similar landscape characteristics and are not necessarily linked geographically. ELU Reserves Woodlands Parklands Site name Total acres in facility Group (acres) (acres) (acres) ABIGAIL ADAMS STATE PARK 10 - - 9 9 ACUSHNET CEDAR SWAMP STATE RESERVATION 7 2,104 - - 2,104 ALEWIFE BROOK PARKWAY 0 - - 3 3 ALEWIFE BROOK RESERVATION 10 - - 136 136 ALLIED VETERANS RINK 0 - - 3 3 AMELIA EARHART DAM 0 - - 2 2 AMES NOWELL STATE PARK 7 - - 612 612 ANGLE TREE MONUMENT RESERVATION 0 - - 0 0 ANTHONY A. LACONTE RINK 0 - - 1 1 APPALACHIAN TRAIL CORRIDOR 0 - - 129 129 APPALACHIAN TRAIL CORRIDOR 1 3 - - 106 106 APPALACHIAN TRAIL CORRIDOR 2 3 - - 462 462 APPALACHIAN TRAIL CORRIDOR 3 3 343 - - 343 ARTHUR WHARTON SWANN SF 3 799 - 51 850 ASHBURNHAM STATE FOREST 5 - 2,211 - 2,211 ASHLAND STATE PARK 7 - - 472 472 ASHMERE LAKE STATE PARK 5 - - 205 205 ASHUWILLTICOOK RAIL TRAIL 0 - - 8 8 ATTITASH PUBLIC ACCESS 0 - - 0 0 BAKER CHOCOLATE FACTORY 0 - - 0 0 BALANCE ROCK STATE PARK 1 - 116 21