Ethnic Conflict in Kokrajhar, India: History and Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State: Assam Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Kokrajhar

State: Assam Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Kokrajhar 1.0 District Agriculture profile 1.1 Agro-Climatic/Ecological Zone g g g A ro Ecolo ical Sub Re ion (ICAR) Eastern Himalayas, Warm Perhumid Eco-Region (16.1), Assam And Benga l Plain, Hot Subhumid To Humid (Inclusion of Perhumid) Eco-Region.(15.3) Agro-Climatic Zone (Planning Eastern Himalayan Region (II) Commission) Agro Climatic Zone (NARP) Lower Brahmaputra Valey Zone (AS-4) List a l the districts or part thereof faling Kamrup, Nalbari, Barpeta, Bongaigaon, Baksa, Chirang, Kokrajhar, Dhubri ans Goalpara under the NARP Zone g p Geo ra hic coordinates of district Latitude Longitude Altitude headquarters 26.19" N to 26.54" N 89.46' E to 90.38' E 48.12mMSL Name and address of the concerned ZRS/ g g g ZARS/ RARS/ RRS/ RRTTS Re ional A ricultural Research Station, Gossai aon Mention the KVK located in the district Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Kokrajhar, Telipara, Gossaiagaon – 783360, Dist: - Kokrajhar, BTC, Assam Name and address of the nearest Agromet AWS at KVK, Kokrajhar (Gossaigaon) and ASS, IMD at RARS, Gossaigaon, Telipara, Kokrajhar BTC Field Unit (AMFU, IMD) for agro- 783360 advisories in the Zone 1.2 Rainfall Normal Normal Normal Onset Normal Cessation RF(mm) Rainy days ( specify week and month) (specify week and month) (number) p p SW monsoon (June-Se ): 2767.0 93 1s t week of June 4th week of Se tember NE Monsoon(Oct-Dec): 115.6 9 - - Winter (Jan- March) 0.0 0 - - Summer (Apr-May) 580.5 37 - - Average Annual 3463.1 139 - - 1.3 Land Geographical Cultivable Forest area Land under Permanent Cultivable Land Barren and Current Other Land put use- area (‘000 area (‘000 ha) (‘000 ha) non- Pastures wasteland under uncultivable Falows falows or non pattern ha) agricultural (‘000 ha) (‘000 ha) Misc. -

Tracing the Continuities of Violence in Bodoland By

Tracing the Continuities of Violence in Bodoland rishav kumar thakur !"#$$% 128 # Shahpur Jat, 1st &oor %'( )'*+, 110 049 '-$,*: [email protected] ('#.,/': www.zubaanbooks.com Published by Zubaan Publishers Pvt. Ltd 2019 In collaboration with the Sasakawa Peace Foundation fragrance of peace project All rights reserved Zubaan is an independent feminist publishing house based in New Delhi with a strong academic and general list. It was set up as an imprint of India’s first feminist publishing house, Kali for Women, and carries forward Kali’s tradition of publishing world quality books to high editorial and production standards. Zubaan means tongue, voice, language, speech in Hindustani. Zubaan publishes in the areas of the humanities, social sciences, as well as in fiction, general non-fiction, and books for children and young adults under its Young Zubaan imprint. Typeset in Arno Pro 11/13 Tracing the Continuities of Violence in Bodoland INTRODUCTION The Bodoland Territorial Autonomous Districts (BTAD), renamed as Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR) in 2020, was created in 2003 as an autonomous region within Assam in response to the long movement for Bodo autonomy. After decades of adopting peaceful means (with sporadic attacks on government property or staff), militant factions of the movement started targeting non-Bodo residents since the late 1980s. Over time, organizations and coalitions have emerged among non-Bodo communities – both recognized as indigenous or as marginalized immigrants such as Adivasis1 and Bengali-speaking Muslims2. -

Deos Contact No

Deputy Commissioner and Sub-Divisional Officer (Civil) as District Election Officers : Name of the STD Landline Sl. No. Name & Designation Contact No Email_Id Election Districts code number 1 Karimganj Anbamuthan M.P., IAS 03843 262345 99523-46765 [email protected] 2 Hailakandi Megha Nidhi Dahal, IAS, DC 03844 222251 88266-05380 [email protected] 3 Cachar Keerti Jalli, IAS, DC 03842 245056 99534-68140 [email protected] 4 Dima Hasao Paul Baruah,ACS, DC 03673 236222 94353-38123 [email protected] 5 Bokajan Dilip Terang, ACS 03675 246011 96780-85165 [email protected] Ng. Chandra Dhwaj Singha, 6 Karbi Anglong 03671 272255 94350-88111 [email protected] ACS West Karbi 7 Isfaqur Rahman, ACS, DC 03677 230030 69017-59500 [email protected] Anglong 8 South Salmara Gurdip Singh Panesar, ACS 03662 286624 94350-80857 [email protected] 9 Dhubri Ananta Lal Gyani, IAS, DC 03662 230050 94350-02981 [email protected] 10 Bilasipara Mridul Yadav, IAS 03667 250275 99200-35952 [email protected] 11 Gossaigaon Ansula Basumatary, ACS 03669 220336 94351-22149 [email protected] 12 Kokrajhar Bhaskar Phukan, ACS 03661 270741 94351-83370 [email protected] 13 Chirang Gautam Talukdar,ACS, DC 03664 241992 98640-34681 [email protected] 14 Bogaigaon Dr. Lakshmi Priya, IAS 03664 230889 70991-90324 [email protected] Dhrubajyoti Das, ACS, 15 Bijni 03668 284647 94350-89620 [email protected] SDO© 16 North Salmara Smt. Pallavi Sarkar, IAS 03664 281439 87782-36728 [email protected] 17 Goalpara Ms. Varnali Deka, IAS, DC 03663 240030 94350-43004 [email protected] -

Dist. Family Planning Co-Ordinator1

Shortlisted Candidates for Final Round Interview for the post of District Family Planning Coordinator under NRHM, Assam Sl Name Address Silchar Road, Word No-1, Hailakandi, Near by D.I.C Office P.O- Rangauti Part -2 1 Ahmed Kibria Laskar Dist- Hailakandi Pin-788155 2 Aparna Barman vill- Barkuriha P.O- Barkuriha dist- Nalbari pin-781348 3 Apurba sharma Vill- Nagaon P.O- Nagaon P.S- Barpeta Dist- Barpeta Pin- 781311 4 Arup kumar sarma Vill- bengapara P.O+P.S- sarthebari Dist- Barpeta Assam , Pin- 781307 5 Baharul Ulum Choudhury vill+P.O+P.S- Moirabari Dist- Morigaon 6 Barnali Barman Ward No-4 P.O- Milanpur, dist- Nalbari, Assam Pin-781337 7 Bhabesh Dutta H.No- 11 Uzan Bazar (Near Raj Bhawan) Guwahati -1 House no- 14, Kanaklata Path, Rukminigaon, Guwahati-781022, Kamrup (M) 8 Bhumika Talukdar Assam 9 Chaitanya Bora Vill- Chamaguri P.o- Gosaibari pin-787033 Lakhimpur 10 Chandana Sharma W/o-Abhijit Das, Barpukhuripar, PO.+Dist. Goalpara, Pin. 783101 Vill- Abhayapuri , M.G Road P.O- Abhayapuri Dist- Bongaigaon Assam, Pin- 11 Devashree Pathak 783384 C/o- Thagen Chandra Nath P.o- Manipur, Vill-Nuagaon, Morigaon, assam, Pin- 12 Diku Moni Nath 782105 13 Dipak Das C/O- Tapan Das , Ward no- 3, P.O- Mariani, Dist- jorhat, Assam 14 Fayez uddin ahmed House No- 115 Gandhibasti road , P.O- Silphukhuri , Guwahati, Assam Pin-781003 15 Hilal uddin Laskar Vill- Tupkhana Pt-1, P.o- Arunachal Dist- Cachar (assam) , Pin- 788025 16 Himangshu Baruah Vill. Salaipara, PO. Bahmolla, Dist. Darrang, Pin. 784522 Meghmallar Sparkle, F/no-204, Zoo- Narengi Road , Surajit -

TERRITORIES of BELONGING Citizenship and Everyday Practices of the State in Bodoland

TERRITORIES OF BELONGING Citizenship and everyday practices of the state in Bodoland Saba Sharma Department of Geography University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Hughes Hall April 2019 Declaration This thesis is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution, except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit of 80,000 words of the Degree Committee for the Faculty of Earth Sciences & Geography. 2 Thesis Summary My thesis looks at the construction of citizenship in the Bodoland Territorial Area Districts (BTAD, or Bodoland for short) in Western Assam, India. The BTAD is an autonomous sub- region within the state of Assam, which in turn is part of a cluster of states in Northeast India. I look primarily at the everyday practices of the state in an ethnically diverse region with a history of separatism, armed militant struggle, and violence between different ethnic groups. Two related strands of difference underlie the notion of citizenship here — the territorialised expression of ethnicity as manifested in the Indian context; and the idea of India’s Northeast as being a space of exception vis-à-vis the rest of the country. -

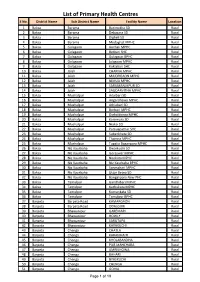

List of Primary Health Centres S No

List of Primary Health Centres S No. District Name Sub District Name Facility Name Location 1 Baksa Barama Barimakha SD Rural 2 Baksa Barama Debasara SD Rural 3 Baksa Barama Digheli SD Rural 4 Baksa Barama Medaghat MPHC Rural 5 Baksa Golagaon Anchali MPHC Rural 6 Baksa Golagaon Betbari SHC Rural 7 Baksa Golagaon Golagaon BPHC Rural 8 Baksa Golagaon Jalagaon MPHC Rural 9 Baksa Golagaon Koklabari SHC Rural 10 Baksa Jalah CHARNA MPHC Rural 11 Baksa Jalah MAJORGAON MPHC Rural 12 Baksa Jalah NIMUA MPHC Rural 13 Baksa Jalah SARUMANLKPUR SD Rural 14 Baksa Jalah SAUDARVITHA MPHC Rural 15 Baksa Mushalpur Adalbari SD Rural 16 Baksa Mushalpur Angardhawa MPHC Rural 17 Baksa Mushalpur Athiabari SD Rural 18 Baksa Mushalpur Borbori MPHC Rural 19 Baksa Mushalpur Dighaldonga MPHC Rural 20 Baksa Mushalpur Karemura SD Rural 21 Baksa Mushalpur Niaksi SD Rural 22 Baksa Mushalpur Pamuapathar SHC Rural 23 Baksa Mushalpur Subankhata SD Rural 24 Baksa Mushalpur Thamna MPHC Rural 25 Baksa Mushalpur Tupalia Baganpara MPHC Rural 26 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Dwarkuchi SD Rural 27 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Goreswar MPHC Rural 28 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Naokata MPHC Rural 29 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Niz Kaurbaha BPHC Rural 30 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Sonmahari MPHC Rural 31 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Uttar Betna SD Rural 32 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Bangalipara New PHC Rural 33 Baksa Tamulpur Gandhibari MPHC Rural 34 Baksa Tamulpur Kachukata MPHC Rural 35 Baksa Tamulpur Kumarikata SD Rural 36 Baksa Tamulpur Tamulpur BPHC Rural 37 Barpeta Barpeta Road KAMARGAON Rural 38 Barpeta Barpeta Road ODALGURI Rural 39 Barpeta -

UBERIZATION – Route List (Modified)

UBERIZATION – Route list (Modified) A) City bus service at Guwahati (SCR service) Total Route Number Base station Route details number No. of buses of bus 1 Khanapara Khanapara to Jalukbari via Paltanbazar 25 2 Basistha Basistha Mandir to Jalukbari via Paltanbazar 15 3 Paltanbazar Kahilipara to Jalukbari via Dispur, Paltanbazar 12 4 Forest Gate Forest Gate to Jalukbari via Chandmari, Church field 25 5 Khanapara Khanapara to Jalukbari via ISBT, NH 37 25 ISBT to Jalukbari via Basistha Chariali, Beltola tiniali, Last Gate, Ganeshguri, 6 ISBT 20 Zoo Road, Chandmari, Kachari 7 Forest Gate Chandrapur to Jalukbari via Forest Gate, Chandmari, Kachari 15 8 ISBT ISBT to Kachari via Saukuchi, Serab bhati, Paltanbazar 15 9 ISBT ISBT to Kachari via Garchuk, Ganeshpara, Dhirenpara, Ambari, Bharalumukh 15 Khanapara to Amingaon via ISBT, Jalukbari 10 Khanapara 15 233 (May be extended up to Changsari, if possible) 11 Paltanbazar Lalmati to Jalukbari via Hatigaon, Ganeshguri, Paltanbazar 7 Khanapara to Khanapara via Sixmile, Ganeshguri, Zoo Road, Hatigaon, 12 Khanapara 7 Narikolbasti, Geeta Mandir, Pathar Kuwari Forest Gate to Amingaon via Chandmari, Kachari 13 Forest Gate 7 (May be extended up to Changsari, if possible) 14 ISBT (Ghy) ISBT (Ghy) to Hajo via Adabari 7 15 ISBT (Ghy) ISBT (Ghy) to Soalkuchi via Adabari 5 16 Soygaon Soygaon to Adabari 5 17 Khanapara Byrnihat to Jalukbari via Basistha Chariali, Lakhara, Khanapara 5 18 Forest Gate Forest Gate to Khanapara via Noonmati, Chandmari, Zoo Road, Ganeshguri 8 B) Short distance service Total Number -

During: March 09 - 15, 2021

UGC HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL Workshop on Disaster Management (During: March 09 - 15, 2021) “LIST OF SELECTED PARTICIPANTS” Sl. No. / Next Promotion Name Name of the Institute Roll No. Due on STATE (WEST BENGAL) 01. DR PAYEL MUKHERJEE Visva-Bharati 11-12-2014 02. SANCHITA BHATTACHARYYA Netaji Subhas Mahavidyalaya 29-07-2018 03. MOUSUMI MUKHOPADHYAY BIDHANNAGAR COLLEGE 17-08-2018 04. SONALI MUKHERJEE SEVA BHARATI MAHAVIDYALAYA 22-07-2019 05. MOUMITA PATRA Raghunathpur College 19-02-2020 06. DR. PROSENJIT MUKHERJEE Bangabasi Evening College 19-04-2020 07. SUSMITA PANDIT MAYNAGURI COLLEGE 17-08-2020 08. SANJAY KARAK NETAJI MAHAVIDYALAYA 02-11-2020 09. SOUMEN BHATTACHARYA Yogoda Satsanga Palpara Mahavidyalaya, Purba Medinipur 01-07-2021 10. BIJOY PRASAD DAS Durgapur Women's College 15-07-2021 11. PARAMITA GHOSH MAYNAGURI COLLEGE 19-07-2021 12. AMLAN KUMAR MITRA RANAGHAT COLLEGE, WEST BENGAL, INDIA 26-03-2022 13. MOUSUMI DEY Ranaghat College 26-06-2022 14. TAPAS KUMAR GHOSH Bankura Sammilani College 20-09-2022 15. BIMALENDU GHOSH Kanchrapara College 07-04-2023 16. DR. APARNA BANERJEE SERAMPORE COLLEGE 14-02-2026 OUTSIDE THE STATE 17. Dr. SONAM YANGCHEN BHUTIA SIKKIM UNIVERSITY 25-02-2024 18. DR. KANTAR BHUSAN NANDI Lokanayak Omeo Kumar Das College 16-03-2014 19. SANJAY BARMAN BASUGAON COLLEGE 01-01-2018 20. MONIKANKONA BODO Marangi Mahabidyalaya (Degree) 31-12-2018 21. DEBENDRA BASUMATARY Basugaon College, Basugaon 01-01-2019 Sl. No. / Next Promotion Name Name of the Institute Roll No. Due on 22. MR JAYANTA BORAH Marangi Mahabidyalaya (Degree) 28-02-2020 23. -

Text Begins Here

SECRETARIAT - 150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100, 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland - TEL: +41 22 791 6033 - FAX: +41 22 791 6506 www.actalliance.org Preliminary Appeal India Relief to conflict affected people in Assam – IND123 Preliminary Appeal Target: US$618,047 Geneva, 10 August 2012 Dear Colleagues, Violent clashes in Assam state of India between the ethnic Bodo community and migrant Muslims from Bangladesh are not new. More than 100 people were killed in communal clashes in 1993. Since then there have been regular small skirmishes. A fresh round of violence erupted on 19 July 2012 when four youths were killed. As of 7 August 2012, 78 people have been killed and approximately 400,000 people from both communities have been forced to leave their villages and seek shelter in camps with hardly any amenities. Most of these displaced people are not willing to return due to the continuing violence. Moreover, in most of the cases, their homes have been burned down. The health and hygiene conditions in the camps are deplorable. There are 117 doctors available for the 400,000 inhabitants in the camps. Five children have died during last few days and many have been diagnosed with malaria. The state Government is trying, without much success, to restore normalcy with the help of central combat forces and other paramilitary forces. The chief minister of the state has demanded a high level intelligence inquiry. The relief support so far has been insufficient. Given the environment of distrust, an intervention of voluntary organizations, especially from secular and philanthropic Institutions to help with resettlement and confidence building, is urgently needed. -

Easternchornicle

SUNDAY, SILCHAR EasternChornicle JULY 4, 2021 5 CONTINUED FROM PAGE 1 As many as 600 FIRs registered Negotiations with ULFA Cattle smuggler injured in police Minister Suklabaidya inaugurates in June against power larceny (I) can progress if it shuns firing while attempting to flee Dihing Patkai National Park prior to this, only five police launched for people to report CHRONICLE NEWS SERVICE with the Gossaigaon case 46/21 has come up. people of the state for conser- stations across the state were financial cyber fraud cases, sovereignty issue: Himanta U/S 289/379/417/307 IPC R/W He said following the declara- vation of nature. Suklabaidya allowed to register cases against said that 112 such cases have GUWAHATI: A cattle smuggler sec 11(1)(a)(d)(e)(h) of PCA Act, tion of Dihing Patkai as nation- called everyone to live in com- power larceny but as of now, all been registered within a span sovereignty and not cede an “I remain hopeful, though at was injured in a police firing R/W sec 184/179 MV Act. al park on World Environment plete communion with nature the police stations have been of four days. inch of our land. For him also the same time nothing can be on Saturday after he had tried He was taken to Sukhanjhora Day on June 5 by Chief Minister, that 'provides us sustenance and authorized to do the same and He mentioned that Assam is there is a compulsion, so there predicted on these issues,” said to flee from police custody at area to identify the house of a Dr.Himanta Biswa Sarma, the keeps us alive'. -

Axom Sarba Siksha Abhijan Mission Kahilipara, Guwahati-19 PERSPECTIVE PLAN of S.S.A-2003-2010 KOKRAJHAR DISTRICT DISTRICT at a GLANCE DISTRICT PROFILE

PERSPECTIVE PLAN (DISTRICT ELEMENTARY EDUCATION PLAN) 2002-2010 DISTRICT - KOKRAJHAR Axom Sarba Siksha Abhijan Mission Kahilipara, Guwahati-19 PERSPECTIVE PLAN OF S.S.A-2003-2010 KOKRAJHAR DISTRICT DISTRICT AT A GLANCE DISTRICT PROFILE Prior to its separation froir. the Goalpara district in 1983, Kokrajhar was a sub-division Goalpara district. It came into existence as a suo-division in 1957 with its headquarters Kokrajhar. It has two sub-divisions, namely Kokrajhar & Gossaigaon. Kokrajhar district is located on the north bank of the Brahmaputra and the western part Assam . The boundary of the district is Bhutan on the north Dhubri district on the sou Bongaigaon district on the East and West Bengal State on the West. ♦:* Total Population Of Kokrajhar District: As Per 200' Name of No Population Child Population in the Literates Revenue of Age Group Circle Villa (0 - 6 ) ges Yrs. M ale Femal Total Male Femal Total Male Femal Total e e e Kokrajhar 12923 12287 25210 12407 235 19910 19322 39232 73532 5054C Rev. Circle 2 2 4 2 Dotma Rev 13298 172 68071 64916 10871 10543 , 21414 41904 30014 71918 Circle 7 Sidli Rev. 11569 134 60306 55385 11342 10493 21835 25651 14961 4061 ^ Circle 1 Total for 25760 24317 50078 14108 Kokrajhar 541 42123 40358 82481 95515 23660 7 Sub Div. 9 3 2 Gossaigao 18676 17678 36355 n Rev. 339 37008 35876 72884 84747 51098 13584 7 9 6 Circle Bhowraguri 27G7i Rev. Circle 93 33866 32200 66066 7351 6316 13667 16648 11028 Total for 22063 20898 42962 10139 Gossaigao 432 44359 42192 86551 62126 16352 5 n Sub. -

A Study of Human Development in Bodoland Territorial Area Districts (BTAD), Assam

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 04, APRIL 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 A Study Of Human Development In Bodoland Territorial Area Districts (BTAD), Assam Priyambee Swargiary Abstract: In the year 1990, United Nations Development Programme [UNDP] introduced a more comprehensive way of measuring human development, i.e. Human Development Index. HDI is a statistical tool used to measure a country’s overall achievement in its s ocial and economic dimensions. Both social and economic dimensions are based on education, health and standard of living. This index has become an alternative to the traditional unidimensional measure of development. HDI plays an important role to broaden the prospect of progress. HDI is an attempt to reflect the certain characteristics such as people’s choices, capabilities, and well being etc. The main objective of the paper is to analyse the key dimension of human development i.e. education, health and standard of living of the pe ople of BTAD. Its empirical evidence has proved to be very meaningful to the Governments all over the world as well as the UN agencies. Index Terms: Development, Human Development Index, Capabilities, Well Being, Standard of Living, Health, Education etc. ———————————————————— 1 INTRODUCTION Bodoland Territorial Council is one of the largest autonomous Area, Population, Town, Block and Villages of BTAD: council in Assam comprising of four districts viz. Kokrajhar, District Area in Population Town Block No. of Chirang, Baksa, and Udalguri. Under the sixth schedule of the sq.km Villages Indian Constitution BTC was formed on 10th February 2003. Kokrajhar 3296 887142 4 11 1068 The autonomous council was carved out of the seven existing Chirang 1923 482162 3 5 508 Baksa 2457 950075 2 10 690 districts viz.