The Oxford Book of Modern Verse 1892 1935

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM Table of Contents

MUsic Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM table of contents Sheet Music ....................................................................................................... 3 Jazz Instruction ....................................................................................... 48 Fake Books........................................................................................................ 4 A New Tune a Day Series ......................................................................... 48 Personality Folios .............................................................................................. 5 Orchestra Musician’s CD-ROM Library .................................................... 50 Songwriter Collections ..................................................................................... 16 Music Minus One .................................................................................... 50 Mixed Folios .................................................................................................... 17 Strings..................................................................................................... 52 Best Ever Series ...................................................................................... 22 Violin Play-Along ..................................................................................... 52 Big Books of Music ................................................................................. 22 Woodwinds ............................................................................................ -

View Booklet

Florence + the Machine CEREMONIALS 2 “Only If For A Night” And I had a dream And I heard your voice About my old school As clear as day And she was there all pink and gold and And you told me I should concentrate glittering It was all so strange I threw my arms around her legs And so surreal Came to weeping (came to weeping) That a ghost should be so practical Only if for a night And I heard your voice As clear as day And the only solution was to stand and fight And you told me I should concentrate And my body was bruised and I was set It was all so strange alight And so surreal But you came over me like some holy rite That a ghost should be so practical And although I was burning, you’re the only Only if for a night light Only if for a night And the only solution was to stand and fight And my body was bruised and I was set alight Madam, my dear, my darling But you came over me like some holy rite Tell me what all the sighing’s about And although I was burning, you’re the only light Tell me what all the sighing’s about Only if for a night And I heard your voice And the grass was so green against my new As clear as day clothes And you told me I should concentrate And I did cartwheels in your honour It was all so strange Dancing on tiptoes And so surreal My own secret ceremonials That a ghost should be so practical Before the service began Only if for a night In the graveyard doing handstands Only if for a night 3 “Shake It Out” Regrets collect like old friends Shake it out, shake it out, shake it out, Here to relive your darkest moments -

A Tuscan Atmosphere

Philadelphia, PA April-May 2012 THEThe Free Student NewspaperGRIFFIN of Chestnut Hill College Senior Class Is Given A Beautiful Send Off MARY MARZANO documenting senior memories ’12 throughout the years including photos and six-word memoirs. On Thursday, April 19, The slide show can now be the class of 2012 gathered in found on Youtube under Senior the Commonwealth Chateau Dinner CHC 2012 SlideShow. (known to many as Sugarloaf) Jessica Khan, Ph.D., for a masquerade ball-themed professor of education, and Senior Dinner. The dress code speaker for the evening was was semi-formal and the seniors cheered to the podium by her and other attendees definitely students. Following Dr. Kahn’s followed that with the men in speech, sophomore Megan ties and ladies dressed to the Gerry and senior Dave Forster nines. Junior class officers Mary presented the Class of 2012 Frances Cavallaro, president, Senior Superlatives. Attending and Chris Ryan, vice-president, seniors were awarded for hosted the entertaining evening. superlatives such as ‘best As attendees arrived wolfpack’, ‘class prankster’, and underclassmen volunteers ‘most fashionable’. images: Jess Veazey ’13 including Michael Yancey ’14 At the conclusion of The class of 2012 and faculty sat down to a wonderfully prepared dinner planned by Jr. on piano greeted them. Official superlatives a group of faculty Class President Mary Frances Cavallaro ‘13 and Jr. Class Vice President Christopher photographer for the evening calling themselves, “The Foolish Jessica Veazey ’13 took souvenir Faculty” serenaded students Ryan ‘13. The Common Wealth Chateau provided a beautiful scene for the dinner. photos in the library before and with a rendition of Bob Dylan’s and Dean of Student Life after dinner. -

Faith Stealer Free

FREE FAITH STEALER PDF Graham Duff,Paul McGann,India Fisher,Conrad Westmaas | none | 01 Oct 2004 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781844351039 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom Faith Stealer - Wikipedia Post a comment. Untitled Page. Gary Russell. But under the guidance of the charismatic Laan Carder, one religion seems to be gathering Faith Stealer at an alarming rate. With the Doctor Faith Stealer Charley catching Faith Stealer of an old friend and C'rizz on the receiving end of some unorthodox religious practices, their belief, hope and faith are about to be tested to the limit. It's time to see the light. Considering my allergic reaction to the last season you can imagine my delight in heading back to the Divergent Universe. Upon entering the Multihaven he is forced to invent his own religion, the Tourists, who start each day with a ritual cup of tea. Faith Stealer all the good work to make him witty and fun to be around again is jettisoned when he stops Charley from being brutally murdered. There is no Faith Stealer of his hunt for Rassilon, which was excitedly whispered at Faith Stealer close of the last story in the Universe. He witnesses his worst nightmare, the TARDIS bursting into a million shards and thus is trapped on this planet with no escape. He thinks it is time he came out of the closet, Faith Stealer is about damn time. There are no stunning revelations about the Doctor, no deep insights but Faith Faith Stealer features the most responsible take on his character since Neverland and for that I am grateful. -

PDF Van Tekst

De Tweede Ronde. Jaargang 15 bron De Tweede Ronde. Jaargang 15. G.A. van Oorschot, Amsterdam 1994 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_twe007199401_01/colofon.php © 2017 dbnl 3 [De Tweede Ronde 1994, nummer 1] Voorwoord Dit Lentenummer bevat in Nederlands proza vier bijdragen: een radio-column van Nico Slothouwer (opgenomen ter nagedachtenis aan onze oud-redacteur wiens ‘Verzameld Werk’ dezer dagen verschijnt), een debuut, van Atie Vogelenzang, en nieuwe verhalen van de twee pijlers van deze rubriek, Frans Pointl en L.H. Wiener. In Nederlandse poëzie werk van zestien medewerkers, onder wie één debutante, Anke Binnerts. Ook in Light Verse begroeten we - naast de nodige coryfeeën - nieuw talent: Yvon Melly, die het thema van de Zingende Zaag gestalte gaf in zelf geïllustreerde knittelverzen. De overige rubrieken staan in het teken van het sinds 1991 weer onafhankelijke Estland. De trotse felheid waarmee de Esten, amper een miljoen in getal, zich inzetten voor hun nationale literatuur, zou een ander zogenoemd ‘klein taalgebied’ als het Nederlandse beschaamd mogen maken. In Essay getuigen de stukken van Jaan Kross en Mati Sirkel van het stelselmatige maar uiteindelijk vergeefse streven van nazistische en communistische zijde om Estlands taalkundige en culturele identiteit te vernietigen. Veelzeggend is Kross' opmerking dat het geweld tegen de Estse schrijvers, vertaald naar Nederlandse verhoudingenin de Tweede Wereldoorlog, zou zijn neergekomen op executie van 45 schrijvers, en gevangenschap of deportatie van nog eens een achthonderdtal, van wie 100 het met de dood zouden hebben bekocht. Vertaald proza bevat, naast werk van Kross, die geldt als Estlands belangrijkste auteur, verhalen van zes andere schrijvers - vaak met een obsessieve of surreële inslag. -

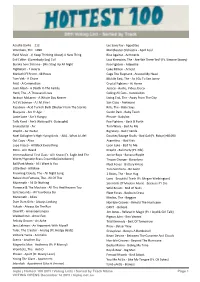

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Track Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

Azealia Banks - 212 Les Savy Fav - Appetites Wombats, The - 1996 Manchester Orchestra - April Fool Field Music - (I Keep Thinking About) A New Thing Rise Against - Architects Evil Eddie - (Somebody Say) Evil Last Kinection, The - Are We There Yet? {Ft. Simone Stacey} Buraka Som Sistema - (We Stay) Up All Night Foo Fighters - Arlandria Digitalism - 2 Hearts Luke Million - Arnold Mariachi El Bronx - 48 Roses Cage The Elephant - Around My Head Tom Vek - A Chore Middle East, The - As I Go To See Janey Feist - A Commotion Crystal Fighters - At Home Juan Alban - A Death In The Family Justice - Audio, Video, Disco Herd, The - A Thousand Lives Calling All Cars - Autobiotics Jackson McLaren - A Whole Day Nearer Living End, The - Away From The City Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! San Cisco - Awkward Kasabian - Acid Turkish Bath (Shelter From The Storm) Kills, The - Baby Says Bluejuice - Act Yr Age Caitlin Park - Baby Teeth Lanie Lane - Ain't Hungry Phrase - Babylon Talib Kweli - Ain't Waiting {Ft. Outasight} Foo Fighters - Back & Forth Snakadaktal - Air Tom Waits - Bad As Me Drapht - Air Guitar Big Scary - Bad Friends Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds - AKA…What A Life! Douster/Savage Skulls - Bad Gal {Ft. Robyn}+B1090 Cut Copy - Alisa Argentina - Bad Kids Lupe Fiasco - All Black Everything Loon Lake - Bad To Me Mitzi - All I Heard Drapht - Bali Party {Ft. Nfa} Intermashional First Class - All I Know {Ft. Eagle And The Junior Boys - Banana Ripple Worm/Hypnotic Brass Ensemble/Juiceboxxx} Tinpan Orange - Barcelona Ball Park Music - All I Want Is You Fleet Foxes - Battery Kinzie Little Red - All Mine Tara Simmons - Be Gone Frowning Clouds, The - All Night Long 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Naked And Famous, The - All Of This Lanu - Beautiful Trash {Ft. -

Songs by Artist

TOTALLY TWISTED KARAOKE Songs by Artist 37 SONGS ADDED IN SEP 2021 Title Title (HED) PLANET EARTH 2 CHAINZ, DRAKE & QUAVO (DUET) BARTENDER BIGGER THAN YOU (EXPLICIT) 10 YEARS 2 CHAINZ, KENDRICK LAMAR, A$AP, ROCKY & BEAUTIFUL DRAKE THROUGH THE IRIS FUCKIN PROBLEMS (EXPLICIT) WASTELAND 2 EVISA 10,000 MANIACS OH LA LA LA BECAUSE THE NIGHT 2 LIVE CREW CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS ME SO HORNY LIKE THE WEATHER WE WANT SOME PUSSY MORE THAN THIS 2 PAC THESE ARE THE DAYS CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) TROUBLE ME CHANGES 10CC DEAR MAMA DREADLOCK HOLIDAY HOW DO U WANT IT I'M NOT IN LOVE I GET AROUND RUBBER BULLETS SO MANY TEARS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE UNTIL THE END OF TIME (RADIO VERSION) WALL STREET SHUFFLE 2 PAC & ELTON JOHN 112 GHETTO GOSPEL DANCE WITH ME (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & EMINEM PEACHES AND CREAM ONE DAY AT A TIME PEACHES AND CREAM (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS (DUET) 112 & LUDACRIS DO FOR LOVE HOT & WET 2 PAC, DR DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN (DUET) 12 GAUGE CALIFORNIA LOVE DUNKIE BUTT CALIFORNIA LOVE (REMIX) 12 STONES 2 PISTOLS & RAY J CRASH YOU KNOW ME FAR AWAY 2 UNLIMITED WAY I FEEL NO LIMITS WE ARE ONE 20 FINGERS 1910 FRUITGUM CO SHORT 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 21 SAVAGE, OFFSET, METRO BOOMIN & TRAVIS SIMON SAYS SCOTT (DUET) 1975, THE GHOSTFACE KILLERS (EXPLICIT) SOUND, THE 21ST CENTURY GIRLS TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD 220 KID X BILLEN TED REMIX LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) WELLERMAN (SEA SHANTY) 2 24KGOLDN & IANN DIOR (DUET) WHERE MY GIRLS AT MOOD (EXPLICIT) 2 BROTHERS ON 4TH 2AM CLUB COME TAKE MY HAND -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Embrace the Darkness by Nicholas Briggs Embrace the Darkness

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Embrace the Darkness by Nicholas Briggs Embrace the Darkness. Embrace the Darkness is a Big Finish Productions audio drama based on the long-running British science fiction television series Doctor Who . Contents. The Doctor and Charley encounter an ancient race in the Cimmerian System, whose return could prove apocalyptic. But as the Darkness envelops the station the Doctor learns that their seemingly evil acts might be more than they appear. The Doctor — Paul McGann — India Fisher Ferras — Lee Moone Haliard — Mark McDonnell Orllesnsa — Nicola Boyce ROSM — Ian Brooker. Trivia. The name of the robotic control system, ROSM, is clearly an homage to the title character Rossum in R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots), a Czech play from 1921, which first introduced the word 'robot' to the general lexicon. In episode 2, the Doctor quotes from Romeo and Juliet ("jocund day stands tiptoe"). This foreshadows the Shakespeare theme of the next play, The Time of the Daleks . External links. Reviews. reviews at Outpost Gallifrey reviews at The Doctor Who Ratings Guide. The Company of Friends: Mary's Story The Silver Turk The Witch from the Well Army of Death. Storm Warning Sword of Orion The Stones of Venice Minuet in Hell Invaders from Mars The Chimes of Midnight Living Legend Seasons of Fear Embrace the Darkness The Time of the Daleks Neverland Zagreus Scherzo The Girl Who Never Was Solitaire. The Creed of the Kromon The Natural History of Fear The Twilight Kingdom Faith Stealer The Last Caerdroia The Next Life Terror Firma Scaredy Cat Other Lives Time Works Something Inside Memory Lane Absolution. -

A History: an Unauthorized History of the Doctor Who Universe Free

FREE A HISTORY: AN UNAUTHORIZED HISTORY OF THE DOCTOR WHO UNIVERSE PDF Lance Parkin | 784 pages | 13 Nov 2012 | Mad Norwegian Press | 9781935234111 | English | Des Moines, IA, United States AHISTORY: Unauthorized History of the Doctor Who Universe (3rd Edition) - Doctor Who Store Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your A History: An Unauthorized History of the Doctor Who Universe. Home 1 Books 2. Add to Wishlist. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Members save with free shipping everyday! See details. All told, this Fourth Edition takes about !!!!! Product Details About the Author. Lance Parkin is a British author, best known for writing fiction and reference books for television series, in particular some of the most influential Doctor Who novels Father Time, The Gallifrey Chronicles, etc. He also worked on the Emmerdale television series as a production assistant. Related Searches. Constituting the largest reference work on Doctor Who ever written, the six-volume About Time strives Constituting the largest reference work on Doctor Who ever written, the six-volume About Time strives to become the ultimate reference guide to the world's longest-running science fiction program. View Product. Who is the Who is the Doctor? In Chicks Digs Time Lords, a host of award-winning female novelists, academics and actresses come In Chicks Digs Time Lords, a host of award-winning female novelists, academics and actresses come together to celebrate the phenomenon that is Doctor Who, discuss their inventive involvement with the A History: An Unauthorized History of the Doctor Who Universe fandom and examine why they adore the series. -

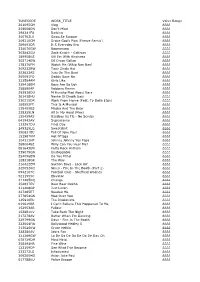

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

Watershed 2013

Watershed 2013 Baker University’s Literature and Arts Magazine Copyright 2013. Baker University. All rights reserved. Production Managing Editor Selection Committee Teresa Morse Kyrie Bair Kate Colby Melinda Hipple Josh Rydberg Faculty Advisor Marti Mihalyi With special thanks to Baker University’s Humanities Department and Jayhawk Ink. Contents -- Literature 8 We are breakfast people 18 This is Just to Say Carly Berblinger Lauren Jaqua 9 The Loyal Listener of the 19 Clementine Phantom Regiment Josh Rydberg Kyrie Bair 19 Regret 10 To Miss Elizabeth Kate Colby Allyson Sass 20 Secret Dialogue 11 Mozart Teresa Morse Parker Roth 21 The Filmmaker 12 Why We Have Chickens Kyrie Bair Kate Colby 22 Exchange of Letters 13 Until the Sunset Parker Roth Rachel Haley 24 In Support of Spinsters 14 Dust Sydney Johnston Melinda Hipple 25 society says 15 Remnants of Refuge Ariel Williams Teresa Morse 26 Power 16 Hunting for Sea Glass Sean Nordeen Haven Ashley 27 To the German Composers of 17 Valentine’s Day, Granada, Spain the 18th Century Allyson Sass Parker Roth 28 Handsome Men 40 Practice Carly Berblinger Allyson Sass 29 Train Watcher 41 Prey Teresa Morse Haven Ashley 30 Honeycrisp Apple 42 Florence and the Machine Josh Rydberg Rachel Haley 31 Tuna Casseroles 43 Kiwi Allyson Sass Erin Wilson 32 Stockton Lake 43 Coconut Kate Colby Melinda Hipple 34 Cypher 44 first things first Haven Ashley Sydney Johnston 35 Color-Patches 45 Courage Kyrie Bair Sean Nordeen 36 When No One is Looking 45 Celery Teresa Morse Shayla Farley 37 Divine Regards 46 Egypt’s Final Pharaoh Carly Berblinger Kyrie Bair 38 Gray 47 The Telescope Melinda Hipple Haven Ashley 39 The Hammerhead Shark Parker Roth Contents -- Art 10 Blind Beauty 24 Who’s Wise Kathryn Ehrhard Milan Piva 14 Petrichor 26 A Different View Ariel Williams BriAnna Garza 17 Lighthouse 30 .. -

The Good 5 Cent Cigar (11/15/2011) University of Rhode Island

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI The Good 5 eC nt Cigar (Student Newspaper) University Archives 11-15-2011 The Good 5 Cent Cigar (11/15/2011) University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cigar Recommended Citation University of Rhode Island, "The Good 5 eC nt Cigar (11/15/2011)" (2011). The Good 5 Cent Cigar (Student Newspaper). Book 105. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cigar/105http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cigar/105 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Good 5 Cent Cigar (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND STUDENT NEWSPAPER SINCE 1971 Volume 61 . 'Just what this country needs ' Tuesday Issue 34 www.ramcigar.com November 15, 2011 URI honors veterans of Iraq, Afghanistan URI's South Korean sister during National Remembrance Day Roll Call BYBROOKECONSTANCElVHTin a moment of silence. Dolan said. "A part of you feels school shares cultural dance News Re:porte:r In the lobby of Swan Hall, like this is such a beautiful way to there were stations set up for peo be honoring them and reading BY LANCE SAN SOUCI ming is a reflection of South News Editor The University of Rhode ple to write letters to those serv names to memorialize them, but Korean culture, a thought he Island honored the nation's vet ing in the military, along with then it's also so sad to read their Samulnori, o-go-mu and hopes students will carry home eranS a little differently this year.