Munton Phil Perspectives 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Readingsample

Interdisciplinary Anthropology Continuing Evolution of Man Bearbeitet von Wolfgang Welsch, Wolf Singer, André Wunder 1. Auflage 2011. Buch. xii, 174 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 642 11667 4 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Gewicht: 499 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Chemie, Biowissenschaften, Agrarwissenschaften > Biowissenschaften allgemein > Evolutionsbiologie Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Intrinsic Multiperspectivity: Conceptual Forms and the Functional Architecture of the Perceptual System Rainer Mausfeld Abstract It is a characteristic feature of our mental make-up that the same percep- tual input situation can simultaneously elicit conflicting mental perspectives. This ability pervades our perceptual and cognitive domains. Striking examples are the dual character of pictures in picture perception, pretend play, or the ability to employ metaphors and allegories. I argue that traditional approaches, beyond being inadequate on principle grounds, are theoretically ill equipped to deal with these achievements. I then outline a theoretical perspective that has emerged from a theoretical convergence of perceptual psychology, ethology, linguistics, and -

Notions Such As 'Truth' Or 'Correspondence to the Objective World' Play No Role in Explanatory Accounts of Perception

Mausfeld, R. (2015). Notions such as ‘truth’ or ‘correspondence to the objective world’ play no role in ex- planatory accounts of perception. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review , DOI: 10.3758/s13423-014-0763-6 Notions such as ‘truth’ or ‘correspondence to the objective world’ play no role in explanatory accounts of perception Rainer Mausfeld University of Kiel Abstract. Hoffman, Singh, and Prakash (2015) intend to show that perceptions are evolutionarily tuned to fitness rather than to truth. I argue, partly in accordance with their objective, that issues of ‘truth’ or ‘veridicality’ have no place in explanatory accounts of perception theory, and rather belong to either ordinary discourse or to philosophy. I regard, however, their general presumption that the evolutionary development of core achievements of the human perceptual system would be primarily determined by aspects of fitness and adaption as unwarranted in light of the evidence available. In our ordinary intuitions about perception, we are convinced that our perceptual apparatus by and large conveys to us a basically ‘truthful’ account of the external world. We are apparently biologi- cally endowed with a predisposition to take certain expressions generated by our perceptual capaci- ties for ‘things in the objective world’. This propensity constitutes a kind of naïve realism that is deeply built-in into our mental make-up (cf. Mausfeld, 2010a). Although naïve realism already foun- ders in the face of most elementary scientific facts, say about the properties of our sense organs, it intellectually expresses some of our deepest convictions about the mental activity of perceiving, namely, being in direct touch with a mind-independent world. -

Das Bedeutsamkeitsproblem in Der Statistik

Das Bedeutsamkeitsproblem in der Statistik Reinhard Niederée und Rainer Mausfeld Im letzten Kapitel (Niederée & Mausfeld, in diesem Band), das dem Thema Ska- lenniveau, Invarianz und „Bedeutsamkeit“ gewidmet war, haben wir uns im we- sentlichen mit der Rolle von skalenniveaubezogenen Invarianzkriterien für numeri- sche Einzelfallaussagen und gesetzesartige Aussagen befaßt. Dabei haben wir zu zei- gen versucht, daß solche Kriterien nicht als aprioristische Bedeutsamkeitspostulate mißverstanden werden dürfen, daß ihnen aber dennoch eine fruchtbare substanzwis- senschaftliche Rolle zukommen kann. In diesem Kapitel wollen wir uns mit verwand- ten Fragen im Bereich der angewandten Statistik befassen. Dabei werden wir die einschlägigen, im letzten Kapitel besprochenen Konzepte als bekannt voraussetzen (vgl. insbesondere die Abschnitte zum Skalenniveau und zu „naiven“ Invarianzkon- zepten). 1 Stevens’ Bedeutsamkeitskonzeption und die Folgen Tatsächlich hatte Stevens (z.B. 1946, 1951) primär Probleme der angewandten Stati- stik im Sinn, als er sein einflußreiches skalenniveaubezogenes Bedeutsamkeitskonzept vorschlug. Konzepte der sog. statistischen Bedeutsamkeit oder Zulässigkeit, welche in der Stevensschen Tradition stehen, finden sich bis heute in einer Vielzahl von einführenden Texten zur angewandten Statistik und zum experimentellen Design. Dabei werden für ein „gegebenes“ Skalenniveau der betrachteten Variablen nur sol- che statistischen Kennwerte (Statistiken) als „bedeutsam“ oder „zulässig“ eingestuft, welche gewisse Invarianzkriterien -

Introduction

1 Introduction: PHILOSOPHY AND SCIENCE OF VISUAL PERCEPTION AND COGNITION Consider your visual experience. In that experience, mind and world meet. The world is presented to you with its shapes, colors, and textures: a green expanse with moving blobs on it; or a whitish grey ribbon with shaped volumes of color moving at great speed. The mind responds by categorizing the objects and anticipating their behavior: here is a park with people playing volleyball, and someone is about to spike the ball; there is a busy highway as you navigate your vehicle at high speed, concerned that the car on the left is weaving a bit. Form, color, and meaning are all present at once in vision, and the objects of other senses usually are experienced as located within this visual world. The world we inhabit, the one in which we live, move, and breathe, is primarily a visual world. For this reason, vision is the most thoroughly studied of the human senses. From antiquity, the disciplines of philosophy and psychology have both given special attention to vision. Indeed, the psychology of perception is the centerpiece of psychological science. Perusing a textbook such as psychologist Stephen Palmer’s Vision Science reveals a broad range of topics, from sensory receptors and the retinal image, to the perception of color, spatial structures, motion, and events, and on to cognitive aspects of perception including object perception, conceptualization, attention, visual memory, imagery, and consciousness. These topic areas are treated experimentally and the phenomena are subject to explicit models framed within recognized theoretical traditions. Although philosophers sometimes have disparaged the notion of psychological science, in this case there can be no question of the just application of the honorific ‘‘science.’’ Sensory perception was the first topical area within psychology to which mathematics was applied, in ancient, medieval, and early modern optical 2 introduction writings (Ch. -

Colour Within an Internalist Framework: the Role of 'Colour' in the Structure of the Perceptual System

to appear in: Jonathan Cohen and Mohan Matthen (eds.). Color Ontology and Color Science. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Colour within an internalist framework: The role of ‘colour’ in the structure of the perceptual system Rainer Mausfeld Colour is, according to prevailing orthodoxy in perceptual psychology, a kind of autonomous and unitary attribute. It is regarded as unitary or homogeneous by assuming that its core properties do not depend on the type of ‘perceptual object’ to which it pertains and that ‘colour per se’ constitutes a natural attribute in the functional architecture of the perceptual system. It is regarded as autonomous by assuming that it can be studied in isolation of other perceptual attributes. These assumptions also provide the pillars for the technical field of colorimetry, and have proved very fruitful for neurophysiological investigations into peripheral colour coding. They also have become, in a technology-driven cultural process of abstraction, part of our common-sense conception of colour. With respect to perception theory, however, both assumptions are grossly inadequate, on both empirical and theoretical grounds. Classical authors, such as David Katz, Karl Bühler, Adhémar Gelb, Ludwig Kardos or Kurt Koffka, were keenly aware of this and insisted that enquiries into colour perception cannot be divorced from general enquiries into the structure of the conceptual forms underlying perception. All the same, the idea of an internal homogeneous and autonomous attribute of ‘colour per se’, mostly taken not as an empirical hypothesis but as a kind of truism, became a guiding idea in perceptual psychology. Here, it has impeded the identification of relevant theoretical issues and consequently has become detrimental for the development of explanatory frameworks for the role of ‘colour’ within the structure of our perceptual system. -

The Scrambling Theorem: a Simple Proof of the Logical Possibility of Spectrum Inversion

Consciousness and Cognition Consciousness and Cognition 15 (2006) 31–45 www.elsevier.com/locate/concog The scrambling theorem: A simple proof of the logical possibility of spectrum inversion Donald D. Hoffman * Department of Cognitive Science, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697, USA Received 20 February 2005 Available online 2 August 2005 Abstract The possibility of spectrum inversion has been debated since it was raised by Locke (1690/1979) and is still discussed because of its implications for functionalist theories of conscious experience (e.g., Palmer, 1999). This paper provides a mathematical formulation of the question of spectrum inversion and proves that such inversions, and indeed bijective scramblings of color in general, are logically possible. Symmetries in the structure of color space are, for purposes of the proof, irrelevant. The proof entails that conscious experiences are not identical with functional relations. It leaves open the empirical possibility that function- al relations might, at least in part, be causally responsible for generating conscious experiences. Function- alists can propose causal accounts that meet the normal standards for scientific theories, including numerical precision and novel prediction; they cannot, however, claim that, because functional relationships and conscious experiences are identical, any attempt to construct such causal theories entails a category error. Ó 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Color; Empirical possibility; Locke; Logical possibility; Nonreductive functionalism; Qualia; Reductive functionalism; Representationalism; Spectrum inversion; Supervenience * Fax: +1 949 824 2307. E-mail address: ddhoff@uci.edu. 1053-8100/$ - see front matter Ó 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2005.06.002 32 D.D. -

The Seductive Allure of Neuroscience Explanations

The Seductive Allure of Neuroscience Explanations Deena Skolnick Weisberg, Frank C. Keil, Joshua Goodstein, Elizabeth Rawson, and Jeremy R. Gray Abstract & Explanations of psychological phenomena seem to gener- vs. with neuroscience) design. Crucially, the neuroscience in- ate more public interest when they contain neuroscientific formation was irrelevant to the logic of the explanation, as information. Even irrelevant neuroscience information in an confirmed by the expert subjects. Subjects in all three groups explanation of a psychological phenomenon may interfere with judged good explanations as more satisfying than bad ones. people’s abilities to critically consider the underlying logic of But subjects in the two nonexpert groups additionally judged this explanation. We tested this hypothesis by giving naı¨ve that explanations with logically irrelevant neuroscience infor- adults, students in a neuroscience course, and neuroscience ex- mation were more satisfying than explanations without. The perts brief descriptions of psychological phenomena followed neuroscience information had a particularly striking effect on by one of four types of explanation, according to a 2 (good nonexperts’ judgments of bad explanations, masking other- explanation vs. bad explanation) Â 2 (without neuroscience wise salient problems in these explanations. & INTRODUCTION (Lombrozo & Carey, 2006; Kelemen, 1999). People also Although it is hardly mysterious that members of the tend to rate longer explanations as more similar to ex- public should find psychological research fascinating, perts’ explanations (Kikas, 2003), fail to recognize circu- this fascination seems particularly acute for findings that larity (Rips, 2002), and are quite unaware of the limits were obtained using a neuropsychological measure. In- of their own abilities to explain a variety of phenomena deed, one can hardly open a newspaper’s science sec- (Rozenblit & Keil, 2002). -

Color Realism and Color Science

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2003) 26, 3–64 Printed in the United States of America Color realism and color science Alex Byrne Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 [email protected] mit.edu/abyrne/www David R. Hilbert Department of Philosophy and Laboratory of Integrative Neuroscience, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60607 [email protected] www.uic.edu/~hilbert/ Abstract: The target article is an attempt to make some progress on the problem of color realism. Are objects colored? And what is the nature of the color properties? We defend the view that physical objects (for instance, tomatoes, radishes, and rubies) are colored, and that colors are physical properties, specifically, types of reflectance. This is probably a minority opinion, at least among color scientists. Textbooks frequently claim that physical objects are not colored, and that the colors are “subjective” or “in the mind.” The article has two other purposes: First, to introduce an interdisciplinary audience to some distinctively philosophical tools that are useful in tackling the problem of color realism and, second, to clarify the various positions and central arguments in the debate. The first part explains the problem of color realism and makes some useful distinctions. These distinctions are then used to expose various confusions that often prevent people from seeing that the issues are genuine and difficult, and that the problem of color realism ought to be of interest to anyone working in the field of color science. The second part explains the various leading answers to the prob- lem of color realism, and (briefly) argues that all views other than our own have serious difficulties or are unmotivated. -

NEOLIBERAL INDOCTRINATION Interview with Prof

NEOLIBERAL INDOCTRINATION Interview with Prof. Rainer Mausfeld (2016) Neoliberalism tells the poor and weak that they are responsible for their misery.. It does its utmost so the true extent of social poverty barely reaches the public, that the public health system despite ever greater spending becomes more inhuman, that social work erodes and hardly anyone does anything against this, that a "re-feudalization bomb" rages in the country and investors seek privatizing the public education system. Jens Wernicke spoke with the perception- and cognition-researcher Rainer Mausfeld on the question how people are atomized and obscured by means of psycho-techniques that make resistance against this inhuman ideology impossible. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- [This interview was published on January 18, 2016 and has been translated from the German. Rainer Mausfeld is a psychology professor and perception- and cognition researcher.] NEOLIBERALISM IS A PHENOMENON AS A SOCIAL IDEOLOGY Neoliberalism tells the poor and weak that they are responsible for their misery. It does its utmost so the true extent of social poverty barely reaches the public, that the public health system despite ever greater spending becomes more inhuman, that social work erodes and hardly anyone does anything against this, that a “re-feudalization bomb” rages in the country and investors seek privatizing the public education system. Jens Wernicke spoke with the perception- and cognition-researcher Rainer Mausfeld on the question how people are atomized and obscured by means of psycho-techniques that make resistance against this inhuman ideology impossible. Mr. Mausfeld, you recently and unexpectedly gained a little fame as a perception- and cognition researcher when your lecture “Why are the Lambs Silent?” suddenly registered an enormous demand on YouTube. -

Perceptual Transparency in Neon Colour Spreading Displays

Perceptual transparency in neon colour spreading displays Vebj¿rn Ekroll¤ and Franz Fauly Institut fÄur Psychologie der Christian-Albrechts-UniversitÄat zu Kiel Olshausenstr. 40, 24118 Kiel, Germany To appear in Perception & Psychophysics, 2002 This is a preprint and may di®er from the published version March 7, 2002 ¤E-mail: [email protected], Phone: +49(0)431-8807534 yE-mail: ®[email protected], Phone: +49(0)431-8807530 Abstract In neon colour spreading displays, both a colour illusion and per- ceptual transparency can be seen. In the this study we investigated the color conditions for the perception of transparency in such displays. It was found that the data are very well accounted for by a general- ization of Metelli's (1970) episcotister model of balanced perceptual transparency to tristimulus values. This additive model correctly pre- dicted which combinations of colours lead to optimal impressions of transparency. Colour combinations deviating slightly from the addi- tive model also looked transparent, but less convincingly so. 1 1 Introduction The phenomenon of neon colour spreading was ¯rst noticed by Varin (1971) and van Tuijl (1975). This illusion owes its name to the apparent di®usion of colour, which can be seen in ¯gure 1. This particular con¯guration consists of a black and blue grid on a `physically white' background. Despite this fact the background close to the blue parts of the grid looks bluish. Other interesting phenomenal facts, pertaining to this illusion (see ¯gure 1), are that the embedded part seems to be `desaturated' compared to the same part viewed in isolation, and that one has the (sometimes rather vague) im- pression of a transparent layer (Bressan, Mingolla, Spillmann, & Watanabe, 1997; Varin, 1971) covering the region of the subjective colour spread. -

Selective Semantic Memory Retrieval: Electrophysiological Correlates of Interference

Selective semantic memory retrieval: Electrophysiological correlates of interference Hellerstedt, Robin; Johansson, Mikael 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hellerstedt, R., & Johansson, M. (2012). Selective semantic memory retrieval: Electrophysiological correlates of interference. Abstract from TeaP 2012 (Tagung experimentell arbeitender Psychologen), Mannheim, Germany. http://www.teap.de/index.php/teap2012/mannheim Total number of authors: 2 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ......................................................... -

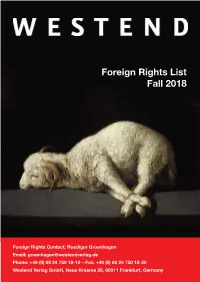

Foreign Rights List Fall 2018

Foreign Rights List Fall 2018 Foreign Rights Contact: Ruediger Gruenhagen Email: [email protected] Phone: +49 (0) 69 24 750 18-10 – Fax: +49 (0) 69 24 750 18-20 Westend Verlag GmbH, Neue Kraeme 28, 60311 Frankfurt, Germany Rainer Mausfeld Rainer Mausfeld is professor at the University of Kiel. Before his retirement, he was the chair of the faculty for perception, and cog- nition studies. He writes on neoliberal ideology, the deconstruction of democracy into an authoritarian surveillance state, and psycho- logical techniques of opinion. With his lectures (such as “How are democracies, and opinions being guided”, and “The power elites fear of the people”) he reaches hundred thousands of listeners. © privat Original Title: Silence of the Lambs Warum schweigen die Lämmer? Wie How the power elite and neoliberal- Elitendemokratie und Neoliberalis- mus unsere Gesellschaft und unsere ism destroy our society Lebensgrundlagen zerstören Original language: German Over the past decades, democracy has been un- Publication in October 2018 304 pages dermined in an unparalleled fashion. Democracy has been replaced by the illusion of democracy; the Including many llustrations public debate has been replaced by an apparatus YouTube: 2 million visits of opinion, and irritation management, and the ideal of the responsible citizen has been replaced by the neoliberal ideal of the politically apathetic WORLD RIGHTS AVAILABLE consumer. Important political decisions are being made by economic and political groups with no democratic legitimation or accountability whatso- ever. The destructive social, ecological, and psy- chological effects of this reign of the elites increas- ingly endangers our society, and the fundaments of our life.