East of Downtown and Beyond Interview with Helena Maria Viramontes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ing the Fj Needs of the Music & Record Ti Ó+ Industry

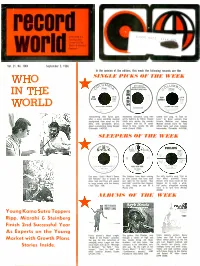

. I '.k i 1 Dedicated To £15.o nlr:C, .3n0r14 Serving The fJ Needs Of The Music & Record ti Ó+ Industry ra - Vol. 21, No. 1004 September 3, 1966 In the opinion of the editors, this week the following records are the WHO SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK LU M MY UNCLE 6 USED TO LOVE IN THE ME BUT SHE DIED y 43192 WORLD JUST LIME A WOMAN Trendsetting Bob Dylan goes Absolutely nonsense song with Gentle love song, "A Time for after a more soothing musical gritty delivery by Miller. Should Love," by Oscar winners Paul background than usual on this catch ears across the country Francis Webster and Johnny ditty, with perceptive lyrics, as Roger, with his TV series Mandel should score for Tony about a precocious teeny bopper about to bow, recalls his odd whose taste and style remains (Columbia 4-43792). uncle (Smash 2055). impeccable (Columbia 4-43768). SLEEPERS OF THE WEEK PHILIPS Am. 7. EVIL ON YOUR MIND , SAID I WASN'T GONNAN TELL 0 00000 TERESA BREARE S AM t - DAVE A1 Duo does "Said I Wasn't Gonna The Uniques have been coming The nifty country song "Evil on Tell Nobody" like it should be up with sounds that have been Your Mind" provides Teresa done. Sam and Dave will appeal just right for the market. "Run Brewer with what could be her to large crowds with tfie bouncy and Hide" could be their biggest biggest hit in quite a while. r/ber (Stax 198). to date. Keep an eye on it Her perky, altogether winning (Paula 245). -

MCA-500 Reissue Series

MCA 500 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-500 Reissue Series: MCA 500 - Uncle Pen - Bill Monroe [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5348. Jenny Lynn/Methodist Preacher/Goin' Up Caney/Dead March/Lee Weddin Tune/Poor White Folks//Candy Gal/Texas Gallop/Old Grey Mare Came Tearing Out Of The Wilderness/Heel And Toe Polka/Kiss Me Waltz MCA 501 - Sincerely - Kitty Wells [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5350. Sincerely/All His Children/Bedtime Story/Reno Airport- Nashville Plane/A Bridge I Just Can't Burn/Love Is The Answer//My Hang Up Is You/Just For What I Am/It's Four In The Morning/Everybody's Reaching Out For Someone/J.J. Sneed MCA 502 - Bobby & Sonny - Osborne Brothers [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5356. Today I Started Loving You Again/Ballad Of Forty Dollars/Stand Beside Me, Behind Me/Wash My Face In The Morning/Windy City/Eight More Miles To Louisville//Fireball Mail/Knoxville Girl/I Wonder Why You Said Goodbye/Arkansas/Love's Gonna Live Here MCA 503 - Love Me - Jeannie Pruett [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5360. Love Me/Hold To My Unchanging Love/Call On Me/Lost Forever In Your Kiss/Darlin'/The Happiest Girl In The Whole U.S.A.//To Get To You/My Eyes Could Only See As Far As You/Stay On His Mind/I Forgot More Than You'll Ever Know (About Her)/Nothin' But The Love You Give Me MCA 504 - Where is the Love? - Lenny Dee [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5366. -

A Never Ending Never Done Bibliography of Multicultural Literature for Younger and Older Children

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 407 388 SP 037 304 AUTHOR Walters, Toni S., Comp.; Cramer, Amy, Comp. TITLE A Never Ending Never Done Bibliography of Multicultural Literature for Younger and Older Children. First Edition. PUB DATE 96 NOTE 51p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature; Adolescents; *American Indian Literature; American Indians; Asian Americans; *Black Literature; Blacks; Children; Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; *Ethnic Groups; *Hispanic American Literature; Hispanic Americans; United States Literature IDENTIFIERS African Americans; *Asian American Literature; Latinos; *Multicultural Literature; Native Americans ABSTRACT People of all ages are addressed in this bibliography of multicultural literature. It focuses on four major ethnic groups: African Americans, Asian Americans, Latino Americans, and Native Americans. Within each category a distinction is made between those works with an authentic voice and those with a realistic voice. An authentic voice is an author or illustrator who is from the particular ethnic group and brings expertise and life experience to his/her writings or illustrations. A realistic voice is that of an author or illustrator whose work is from outside that experience, but with valuable observations. An asterisk notes the distinction. No distinction is drawn between juvenile literature and adult literature. The decision is left to the reader to make the choices, because some adult literature may contain selections appropriate to children. Two appendices provide: a selected annotated bibliography (14 entries) on multiethnic/multicultural literature references and analyses and sources of multiethnic/multicultural books.(SPM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

ED371765.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 371 765 IR 055 099 AUTHOR Buckingham, Betty Jo; Johnson, Lory TITLE Native American, African American, Asian American and Hispanic American Literature for Preschool through Adult. Hispanic American Literature. Annotated Bibliography. INSTITUTION Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE Jan 94 NOTE 32p.; For related documents, see IR 055 096-098. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Authors; Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; *Hispanic Arerican Literature; *Hispanic Americans; Minority Groups; Nonfiction; Picture Books; Reading Materials IDENTIFIERS Iowa ABSTRACT This bibliography acknowledges the efforts of authors in the Hispanic American population. It covers literature by authors of Cuban, Mexican, and Puerto Rican descent who are or were U.S. citizens or long-term residents. It is made up of fiction and non-fiction books drawn from standard reviewing documents and other sources including online sources. Its purpose is to give users an idea of the kinds of materials available from Hispanic American authors. It is not meant to represent all titles or all formats which relate to the literature by authors of Hispanic American heritage writing in the United States. Presence of a title in the bibliography does not imply a recommendation by the Iowa Department of Education. The non-fiction materials are in the order they might appear in a library based on the Dewey Decimal Classification systems; the fiction follows. Each entry gives author if pertinent, title, publisher if known, and annotation. Other information includes designations for fiction or easy books; interest level; whether the book is in print; and designation of heritage of author. -

EXPRESSIONS of MEXICANNESS and the PROMISE of AMERICAN LIBERALISM by EINAR A. ELSNER, B.A., M.A. a DISSERTATION in POLITICAL

EXPRESSIONS OF MEXICANNESS AND THE PROMISE OF AMERICAN LIBERALISM by EINAR A. ELSNER, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN POLITICAL SCIENCE Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dean of the Graduate School August, 2002 Copyright 2002, Einar A. Eisner ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I completed my graduate coursework at Texas Tech University and wrote this dissertation while teaching at Sul Ross State University. Many good men and women in both institutions helped and inspired me along the way. At Sul Ross, I had the pleasure and good fortune of working in an environment of conviviality and intellectual curiosity. Jimmy Case, the department chair, was there for me every time I needed him and inspired me to teach with passion. CUff Hirsch appeared on the shores of my consciousness and provided me with guidance at crucial turns. Ed Marcin welcomed me into his Ufe with a warm abrazo and Mark Saka never ceased to remind me of the need to keep writing. I owe much intellectual development to Daniel Busey, the most inquisitive of my students, and my enthusiasm for teaching to the hundreds of students who took my courses. I will never forget the hours we spent together in the classroom! For reasons too numerous to list here, I am also gratefiil to other people at Sul Ross and the community of Alpine. They are Jay Downing, Nelda Gallego, Paul Wright, Dave Cockrum, Sharon Hileman, Pete Gallego, Abe Baeza, Luanne Hirsch, Carol Greer, Hugh Garrett, Rhonda Austin, John Klingeman, Jon Ward, Jeff Haynes, Eleazar Cano, many of my fellow Kiwanians, and, last but not least, R.C. -

Bridge Making Potential in Ana Castillo's So Far from God and the Guardians

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Fall 2016 Illustrations of Nepantleras: Bridge Making Potential in Ana Castillo's So Far From God and The Guardians Amanda Patrick Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation Patrick, Amanda, "Illustrations of Nepantleras: Bridge Making Potential in Ana Castillo's So Far From God and The Guardians" (2016). All Master's Theses. 558. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/558 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ILLUSTRATIONS OF NEPANTLERAS: BRIDGE MAKING POTENTIAL IN ANA CASTILLO’S SO FAR FROM GOD AND THE GUARDIANS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Literature by Amanda Patrick November 2016 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Amanda Patrick Candidate for the degree of Master of Arts APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Christine Sutphin, Committee Chair ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Christopher Schedler ______________ -

Annual Threat Assessment

HEARING OF THE HOUSE PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE ANNUAL THREAT ASSESSMENT WITNESS: MR. DENNIS C. BLAIR, DIRECTOR OF NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE CHAIRED BY: REPRESENTATIVE SILVESTRE REYES (D-TX) LOCATION: 334 CANNON HOUSE OFFICE BUILDING, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 9:00 A.M. ET DATE: WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2009 RELATED DOCUMENTS: 1) Statement for the Record REPRESENTATIVE SILVESTRE REYES (D-TX): Good morning. The committee will please come to order. Today we convene the first public hearing of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence for the 111th Congress. Before I welcome our new members I want to remind everybody we’re having this hearing today in what I call the home of Chairman Sonny Montgomery, someone that championed issues for America’s veterans, someone that’s highly regarded and revered, not just in Congress but by veterans everywhere. So we are very appreciative to Chairman Filner for allowing us to borrow this very historic hearing room here. With that I would like to extend a warm welcome to the new members of the committee, Mr. Smith and Mr. Boren, Ms. Myrick, Mr. Miller, Mr. Kline and Mr. Conaway. And I’d also like to welcome back to our returning members from previous service with the committee, my vice chair, Mr. Hastings, welcome back, and Mr. Blunt as well. Director Blair, welcome. This morning we’re pleased that you are here, and happy to see you today. We also want to congratulate you on your recent confirmation and wish you well as you go forward under these difficult times that we’re facing today as a nation. -

Social Criticisms As Reflected Through Characters’ Life Experiences in Viramontes’ Under the Feet of Jesus

SOCIAL CRITICISMS AS REFLECTED THROUGH CHARACTERS’ LIFE EXPERIENCES IN VIRAMONTES’ UNDER THE FEET OF JESUS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By BERBUDI YUDOSUNU CANDRAJIWA Student Number: 024214008 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 ii iii iv To my family my mom Nunuk Supriyati, my dad Yudi Mulya, my brother Hapsoro Widi Wibowo, my sister Philia Sampaguita. In the Memory of my late father Soebijanto Wirojoedo v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to say thank you to someone over there who is always waiting for me in my search of faith. Mr. Jesus. I owe Him a lot and I would like to know Him better. I owe an enormous debt to Ni Luh Putu Rosiandani, S.S., M.Hum, for her outrageous counsel, encouragement, prayer, patience, and much more in guiding my in my thesis. My deep gratitude is for my family, my mom Nunuk Supriyati, my late father Soebijanto Wirojoedo, my dad Yudi Mulya, my brother Hapsoro Widi Wibowo, my sister Philia Sampaguita and my little hairy brother Bule, and all my relatives, thanks for being one. My sincere gratitude is for my beloved Mira, for being someone special in my life. Thanks for the encouragement, prayer and love that motivate me in finishing this thesis. My second family, Te’ Puji, Eyang Bantar, Mogi, thanks for the valuable support. My friends, Galang Wijaya, Jati ‘Kocak’, Andika ‘Jaran’, Tiara Dewi, Dyah Putri ‘Tiwik’, Gideon Widyatmoko, Budi Utomo, Ari ‘Inyong’, Dimas Jantri, Teguh Sujarwadi, Putu Jodi, Pius Agung ‘Badu’, Adi Ariep, Yudha ‘Cumi’, lilik, q-zer, Widi Martiningsih, Wahyu Ginting, Yabes Elia, Sugeng Utomo, Ditto, Frida, Bigar Sanyata, Nikodemus, Wahmuji, Anna Elfira, Tyas P Pamungkas, Prita, and all the names I have not mentioned here, that have shared vi great story, thought, and moments with me, thanks guys for the bitter-sweet story we made. -

Cleveland State Community College 2014 Edition

Cleveland State Community College 2014 Edition ENGLISH DEPARTMENT Editor: Julie Fulbright Graphic Design and Production: CSCC Marketing Department Printer: Dockins Graphics, Cleveland, Tenn. Copyright: 2014 All Rights Reserved Front cover photography by: Julie Fulbright Cleveland State Community College www.clevelandstatecc.edu CSCC HUM/13095/04282014 - Cleveland State Community College is an AA/EEO employer and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability or age in its program and activities. The following department has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the non- discrimination policies: Human Resources P.O. Box 3570 Cleveland, TN 37320-3570 [email protected] Table of Contents Written By Title Photo/Drawing By: Page Michael Whaley, Jr. Legacies Rebecca Tedesco 1 Kim Frank A Snowy Evening Julie Fulbright 2 Arielle Saint-Loth A Rose to Emily Chet Guthrie 3 La’Trayier Williamson Cave In Chet Guthrie 4 Jen O’Neal The Black Spot Marchelle Wear 5-8 Mark Partain ABC’s of College Degrees Marchelle Wear 9 Poems Kim Frank 10 Ode to Santiago Mark Partain 11 Wormwood Chet Guthrie 12 Carolyn Price My Greatest Inspiration Marchelle Wear 13-14 Ashley Gentry The Cask of Amontillado Andy Foskey 15-17 Daddy Come Home Chet Guthrie 18 Chet Guthrie Comet Fall Chet Guthrie 19 Deep Doe Eyes Marchelle Wear 20 Farewell Marchelle Wear 21 Life Marchelle Wear 22 A Beast It Was Marchelle Wear 23-30 Tonya Arsenault The Angel with the Smallest Wings Tonya Arsenault 31 Anonymous Untitled 32 Colby Denton Immortal Andy Foskey 33-34 Dixie Sandlin The Monster in Me Dixie Sandlin 35-36 Zac Parker The Divine Parody Chet Guthrie 37 Delena Richeson Sunsets Julie Fulbright 38 Marriage and Mismatched Socks Julie Fulbright 39 Kaitlin Loseby Untitled Julie Fulbright 40 Jacob Taylor Contingency Marchelle Wear 41-42 William White Haiku Julie Fulbright 43 Table of Contents - Continued. -

March 02, 2009 ARTIST VARIOUS TITLE Songs of Love, Loss and Longing SA

SHIPPING DATE: February 16, 2009 (estimated) STREET DATE: March 02, 2009 ARTIST VARIOUS TITLE Songs Of Love, Loss And Longing LABEL Bear Family Records CATALOG # BCD 16632 PRICE-CODE AR EAN-CODE ISBN-CODE 978-3-89916-420-6 FORMAT CD digipac with 64-page booklet GENRE Country / Rockabilly TRACKS 28 PLAYING 72:48 TIME SALES NOTES It's been argued that just about every song ever written – one way or another – is a love song. Even the ones about Hot Rod Lincolns. Some of them are a bit more idiosyncratic than others, but they all get down to the same basic emotions. And where there's love, there's likely to be loss and longing. You might as well sing about it. You'll probably feel better and you might even make a few bucks in the process. This collection brings together 28 songs about love, loss and longing. You can also throw in regret, just for good measure. Because country music has always been grittier and more down to earth than mainstream pop, these songs are even more powerful. This is one of Bear Family's theme collections, drawing often-overlooked tracks from some of country music's strongest performers and performances from over the past half a century. This is music that hasn't been reissued to death; in some cases it hasn't been reissued at all. It's just a good, honest, collection of some of the finest tracks by some of the best country artists. Names like Hank Williams, Johnny Cash, Faron Young, Patsy Cline, Eddy Arnold, Marty Robbins, George Jones, Hank Snow, Don Gibson, Jim Reeves and Merle Haggard. -

House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence

HEARING OF THE HOUSE PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE ANNUAL THREAT ASSESSMENT WITNESS: MR. DENNIS C. BLAIR, DIRECTOR OF NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE CHAIRED BY: REPRESENTATIVE SILVESTRE REYES (D-TX) LOCATION: 334 CANNON HOUSE OFFICE BUILDING, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 9:00 A.M. ET DATE: WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2009 RELATED DOCUMENTS: 1) Statement for the Record REPRESENTATIVE SILVESTRE REYES (D-TX): Good morning. The committee will please come to order. Today we convene the first public hearing of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence for the 111th Congress. Before I welcome our new members I want to remind everybody we’re having this hearing today in what I call the home of Chairman Sonny Montgomery, someone that championed issues for America’s veterans, someone that’s highly regarded and revered, not just in Congress but by veterans everywhere. So we are very appreciative to Chairman Filner for allowing us to borrow this very historic hearing room here. With that I would like to extend a warm welcome to the new members of the committee, Mr. Smith and Mr. Boren, Ms. Myrick, Mr. Miller, Mr. Kline and Mr. Conaway. And I’d also like to welcome back to our returning members from previous service with the committee, my vice chair, Mr. Hastings, welcome back, and Mr. Blunt as well. Director Blair, welcome. This morning we’re pleased that you are here, and happy to see you today. We also want to congratulate you on your recent confirmation and wish you well as you go forward under these difficult times that we’re facing today as a nation. -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3700-3999

RCA Discography Part 12 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3700-3999 LPM/LSP 3700 – Norma Jean Sings Porter Wagoner – Norma Jean [1967] Dooley/Eat, Drink And Be Merry/Country Music Has Gone To Town/Misery Loves Company/Company's Comin'/I've Enjoyed As Much Of This As I Can Stand/Howdy Neighbor, Howdy/I Just Came To Smell The Flowers/A Satisfied Mind/If Jesus Came To Your House/Your Old Love Letters/I Thought I Heard You Calling My Name LPM/LSP 3701 – It Ain’t necessarily Square – Homer and Jethro [1967] Call Me/Lil' Darlin'/Broadway/More/Cute/Liza/The Shadow Of Your Smile/The Sweetest Sounds/Shiny Stockings/Satin Doll/Take The "A" Train LPM/LSP 3702 – Spinout (Soundtrack) – Elvis Presley [1966] Stop, Look And Listen/Adam And Evil/All That I Am/Never Say Yes/Am I Ready/Beach Shack/Spinout/Smorgasbord/I'll Be Back/Tomorrow Is A Long Time/Down In The Alley/I'll Remember You LPM/LSP 3703 – In Gospel Country – Statesmen Quartet [1967] Brighten The Corner Where You Are/Give Me Light/When You've Really Met The Lord/Just Over In The Glory-Land/Grace For Every Need/That Silver-Haired Daddy Of Mine/Where The Milk And Honey Flow/In Jesus' Name, I Will/Watching You/No More/Heaven Is Where You Belong/I Told My Lord LPM/LSP 3704 – Woman, Let Me Sing You a Song – Vernon Oxford [1967] Watermelon Time In Georgia/Woman, Let Me Sing You A Song/Field Of Flowers/Stone By Stone/Let's Take A Cold Shower/Hide/Baby Sister/Goin' Home/Behind Every Good Man There's A Woman/Roll