Old Shropshire Life (1904)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preen News Summer 2019 IMPORTANT: If You Wish to Receive Personal Copies of These Newsletters, Please Complete the GDPR Form on the Back Page 1

Preen News Summer 2019 IMPORTANT: If you wish to receive personal copies of these Newsletters, please complete the GDPR form on the back page 1. Preen Reunion 2019 The 2019 reunion was held in Church Preen Village Hall on Saturday 22 June. It was a bright sunny day, a pleasant change for the recent weather. 24 members were present and the meeting started at 10.30. Normally it would have started with a talk on the family to be featured at this meeting. However on this occasion the topic was the history of Preen Manor (since we believe the family took its name from this Domesday Manor) and that was described in the programme given to everyone who attended. So we proceeded to the AGM, since there were important decisions to be taken. Group Photo of those attending AGM for the Preen Family History Study Group held on 22 June 2019 in Church Preen Present: (shown in the group photo) Philip Davies (F32) - Chairman and Publicity Officer Sue Laflin (F03) - Editor and Archivist Andy Stevens (F27) - Webmaster Also present: Michael Preen (F05), Patricia Preen (F05), Angela De'ath (F05), Philip Preen (F04), Patricia Preen (F04), Barry Kirtlan (F34), Maureen Foxall (F34), Douglas Round (F34), Vera Round (F34), Eric Beard (F32), Colin Preen (F07), Ann Preen (F07), Marion Bytheway (F03), Phillip Bytheway (F03), Philip Barker (F03), Pauline Davies (F32), Jan Edwards (F32), Kenneth Pugh (F04), Edith Pugh (F04), Malcolm Preen (F09) and Rita Preen (F09). 1 Minutes of 2019 AGM continued. 1) The minutes of the 2018 meeting were accepted as a correct record. -

All Stretton Census

No. Address Name Relation to Status Age Occupation Where born head of family 01 Castle Hill Hall Benjamin Head M 33 Agricultural labourer Shropshire, Wall Hall Mary Wife M 31 Montgomeryshire, Hyssington Hall Mary Ann Daughter 2 Shropshire, All Stretton Hall, Benjamin Son 4 m Shropshire, All Stretton Hall Sarah Sister UM 19 General servant Shropshire, Cardington 02 The Paddock Grainger, John Head M 36 Wheelwright Shropshire, Wall Grainger, Sarah Wife M 30 Shropshire, Wall Grainger, Rosanna Daughter 8 Shropshire, Wall Grainger, Mary Daughter 11m Church Stretton 03 Mount Pleasant Icke, John Head M 40 Agricultural labourer Shropshire, All Stretton Icke Elisabeth Wife M 50 Shropshire, Bridgnorth Lewis, William Brother UM 54 Agricultural labourer Shropshire, Bridgnorth 04 Inwood Edwards, Edward Head M 72 Sawyer Shropshire, Church Stretton Edwards, Sarah Wife M 59 Pontesbury Edwards Thomas Son UM 20 Sawyer Shropshire, Church Stretton Edwards, Mary Daughter UM 16 Shropshire, Church Stretton 05 Inwood Easthope, John Head M 30 Agricultural labourer Shropshire, Longner Easthope, Mary Wife M 27 Shropshire, Diddlebury Hughes, Jane Niece 3 Shropshire, Diddlebury 06 Bagbatch Lane ottage Morris James Head M 55 Ag labourer and farmer, 7 acres Somerset Morris Ellen Wife M 35 Shropshire, Clungunford Morris, Ellen Daughter 1 Shropshire, Church Stretton 07 Dudgley Langslow, Edward P Head M 49 Farmer 110 acres, 1 man Shropshire, Clungunford Langslow Emma Wife M 47 Shropshire, Albrighton Langslow, Edward T Son 15 Shropshire, Clungunford Langslow, George F Son -

Shrewsbury and Atcham Constituency

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED, NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Shropshire Council Election of a Member of Parliament for Shrewsbury and Atcham Constituency Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a Member of Parliament for Shrewsbury and Atcham will be held on Thursday 8 June 2017, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. One Member of Parliament is to be elected. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Names of Signatories Name of Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Candidate Assentors BULLARD 42 Hereford Road, Shrewsbury, Green Party Newby Anthony J(+) Lemon Christopher J(++) (+) (++) Emma Catherine SY3 7RD Hayek Thomas J M Egarr Gareth S Mary Bell Charlotte A Latham David M Hayek Tereza Gilbert Peter J Dean Julian D G Lavelle Martha C DAVIES 49 Queens Park Road, Labour Party Mosley Alan N(+) Hudson Keith R(++) (+) (++) Laura Louisa Birmingham, B32 2LB Peacock Diane Bramall Anna E Pardy Kevin J Clarke John E Jones Ioan G Taylor Harry T G Moseley Pamela A Mosley Jacqueline A FRASER (address in the Shrewsbury and Liberal Democrats Craddock David(+) Baker Beverley J(++) (+) (++) Hannah Atcham Constituency) Vasmer David Lea Robert C Clark Daniel A Beardwell Martin W Faherty John M Lewis Caroline L Jones Neil D Evans Roger A HIGGINBOTTOM Rea Bank, Weir Road, Hanwood, UK Independence Party Burgess Frank J.H.(+) Conway David J(++) (+) (++) Edward Arthur Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY5 8LA Burgess Jennifer Moxon Dylan P Gretton Jane D Faulkner Wayne J Price John K Morgan David J Lee Ethel Lee Douglas R KAWCZYNSKI 5 The Anchorage, Coton Hill, Conservative Party Morris Daniel O(+) Coward Beryl J(++) (+) (++) Daniel Robert Shrewsbury, SY1 2DP Candidate Picton Lezley M Jones Valerie A Potter Edward A Phillips Alexander G Adams Peter M Boulger Georgina A Carroll Dean S Nutting Peter A 4. -

Village Directory2019

Village Directory 2019 ACTON BURNELL, PITCHFORD, FRODESLEY, RUCKLEY AND LANGLEY Ewes and lambs near Acton Burnell The Bus Stop at Frodesley CONTENTS Welcome 3 Shops and Post Offices 15 Defibrillators 4 Pubs, Cafes and Restaurants 15 The Parish Council 5 Local Chemists 16 Meet your Councillors 6 Veterinary Practices 16 Policing and Safety 8 Pitchford Village Hall 17 Health and Medical Services 8 Local Churches 18 Local Medical Practices 9 Local Clubs and Societies 19 Local Hospitals 10 Concord College Parish Rubbish Collection and Recycling 11 Swimming Club 20 Parish Map 12 Schools and Colleges 21 Bus Routes and Times 13 Acton Burnell WI 22 Libraries 14 Information provided in this directory is intended to provide a guide to local organisations and services available to residents in the parish of Acton Burnell. The information contained is not exhaustive, and the listing of any group, club, organisation, business or establishment should not be taken as an endorsement or recommendation. While every effort has been made to ensure that the information included is accurate, users of this directory should not rely on the information provided and must make their own enquiries, inspections and assessments as to suitability and quality of services. Village Directory 2019 WELCOME Welcome to the second edition of the Parish Directory for the communities of Acton Burnell, Pitchford, Frodesley, Ruckley and Langley. We have tried to include as much useful information as possible, but if there is something you think is missing, or something you would like to see included in the future, please let us know. We would like to thank the Parish Council for continuing to fund both Village Views and the Directory. -

SHROPSHIRE. L KELLY's X.O

1 400 ROWTON. SHROPSHIRE. l KELLY'S x.o. who is lord of the manor, and Mr. George Ore Hopkins. I Letters throun-h Wellington. The nearest money order office 'fhe soil is of a mixed nature and good; l!nbsoil, sand and is at High Ercall & telegraph office at Wellington clay. The chief crops are wheat, barley and turnips. The area is about 770 acres; the population is included in High Board School, Ellerdine, erected in I883, for 6o children; Ercall. average attendance, 65; William Mills, master Ellerdine. Rowton. Cold Ha.tton. Bourne Erlwin, farmer Hopkins George Ore Ball John, tailor Buttery Charwtte (Mrs.), shopkeeper Wynne Reginald, Rowton castle Clay Richard, butcher Cartwright James, boot & shoe maker . .Adney Richard, farmer Colley John, farmer Cotterill Edwin (exors. of), farmers, Bailey Prances (Mrs.), farmer Icke Robert, farmer New house llnttery Jolm, blacksmith, & deputy Lloyd Thomas, farmer Ferrington William, farmer registrar of births & deaths for En•all Nit!klin Samnt:l, boot & shoe maker Hopwood Wm. Royal Oak P.R. Heath Magna sub-district, Wellington union Pitchford John, farmer, Potford Higginson William, farmer Buttery Thomas, farmer Ridgway George, blacksmith Morris William, farmer Edwards Mary (Mrs.;, shopkeeper Webb John, Seven Stars P.H Pardoe Thomas, farmer Hopkins Geo. Ore, farmer & landowner Whitfield :Francis, farmer Shakeshaft William Robert, farmer & Lewis Richard, carpenter Whitfield John, farmer assistant overseer Price Edward, rate collector Wilkes George, farmer Taylor Hugh, farmer Shakeshaft Joseph, farmer Wr:ght George, farmer Taylor John, farmer RUDGE is a small township in this county, forming part Boycott esq. D.L., J.P. who is sole landowner. -

A Vicar's Life

A Vicar’s Life: Rural communities at the heart of BBC documentary Four clergy in the Diocese of Hereford were the focus of A Vicar’s Life, a six-part documentary series broadcast on BBC Two in 2018. The observational documentary followed three established vicars and a new curate over a six-month period as they ministered at the heart of rural communities, christening babies, marrying couples and burying loved ones. Camera crews spent six months capturing the life and times of parishes stretching from the beautiful small market town of Much Wenlock in the north of the diocese, to Breinton and the west of Hereford and up into the Black Mountains. However, this series was no Vicar of Dibley as their modern day rural ministry sees them tackle pressing social problems of today including, homelessness, dementia, farm sell offs and supporting refugees. This is all against the backdrop of a Church looking to grow today’s generation of Christians, as well as balance the books and maintain hundreds of historic churches. The series shows inspiring local leadership sharing a Christian message of hope and the breadth of church experiences, which are ensuring there is a church for the future for all people in all places. The Bishop of Hereford, the Rt Revd, Richard Frith said: ‘I’m delighted that the spotlight is on the worship and faith in action in our rural diocese and on the incredibly valuable role our clergy and church members play in communities large and small. ‘In these times of austerity cuts and a reduction in the voluntary sector the Church is often the only organisation left helping those in need, particularly in our very rural parts where the church building itself is the only focal place where a community can gather together. -

Minutes of Council Meeting Held on 5Th June 2019 at Cressage Village Hall at 7Pm Present: Cllr

CRESSAGE, HARLEY AND SHEINTON PARISH COUNCIL Parish Clerk/RFO Rebecca Turner, The Old Police House, Nesscliffe, SY4 1DB Telephone: 01743 741611, email: [email protected] Website: www.cressageharleysheinton.co.uk Minutes of Council Meeting held on 5th June 2019 at Cressage Village Hall at 7pm Present: Cllr. Quenby (Chairman), Cllrs. Aston, Bott, Campbell, Esp, Lawrence and Todd Absent: None In attendance: Clerk: Rebecca Turner, Shropshire Cllr. Claire Wild, PS Ram Aston, 13 members of the public 19/1920 WELCOME TO CLLR. PAUL ASTON & SIGNING OF DECLARATION OF ACCEPTANCE OF OFFICE Cllr. Paul Aston was welcomed to the meeting and it was noted he had signed his declaration of acceptance of office prior to the start of the meeting, duly witnessed by the clerk. Cllr. Aston said he had been in the village 3 years and had been instrumental in securing funds to renovate the Village Hall. He had applied to be on the parish council to improve the village for the community. 20/1920 PRESENTATION TO FORMER COLLEAGUE AND CHAIRMAN The Vice Chairman, Cllr. Bott, gave a presentation to former councillor Richard Tipper. Councillors had collected funds privately and purchased a thank you gift and card for his service on the council. Richard Tipper thanked the council and Cllr. Claire Wild for working with him and for their support when he was chair. 21/1920 PERSONS PRESENT & RECEIVE APOLOGIES & REASONS FOR ABSENCE As recorded above. 22/1920 DISCLOSURE OF PECUNIARY INTERESTS Cllr. Bott declared a pecuniary interest in item 32/1920a - payments to his company. 23/1920 DISPENSATION REQUESTS None. -

Preen News 2019

PREEN NEWS 2019 1) Preen Reunion 2019 Last year I found it very difficult to organise the Reunion and so I decided, reluctantly, that I could not do so again this year. Luckily Rev. Phillip Bytheway came to the rescue and volunteered to organise a reunion in Church Preen, the centre from which the family originated. So I am happy to tell you that: - The Preen Family History Study Group are holding their next Annual Reunion on Saturday 22 June 2019 In Church Preen Village Hall, starting 10am The day will offer friends and relations the opportunity to come along and enjoy a good chat about their own family history and the Preen family in general. After morning tea/coffee, there will be talks about the Preen family and general research topics. This will be followed by the AGM, lunch, a Group Photocall and afternoon activities. The Gardens of Preen Manor will be open, Entry price £6.00 at entry. The nearest Railway Station is Church Stretton. There is a possibility of transport for a very small number. There is plenty of accommodation in and near Church Stretton. For example: - The Bottle and Glass, Mynd House, The Hayloft., Victoria House, Sayang House or The Bucks Head. Booking arrangements… The cost is £15 per person. To reserve your place: Please supply your details by completing the form below and sending it, with a cheque (payable to Rev P. Bytheway), to ‘2019 Reunion’, Buxton Cottage, All Stretton, Shropshire SY6 6JU England. Confirmation and further details will be sent when we receive your Booking Form and cheque. -

Planning for a Flourishing Shropshire in the Burnell and Severn Valley Local Joint Committee Area

Planning for a flourishing Shropshire in the Burnell and Severn Valley Local Joint Committee area This leaflet asks your views on Issues and Options for an important Development Plan Document (DPD), called the “Site Allocations and Management of Development DPD”. It is important that you get involved. This is about the places where you live, shop, play, go to school, work, travel, walk... things will change - but together we can try to ensure that it is for the better. 1 Issues and Options for the Site Allocations and Management of Development DPD Introduction Your views This Development Plan Document (DPD) is very important, and will shape your local area over the years ahead. This is your first opportunity to influence it, at the earliest stage in its preparation. We are interested in your views, concerns and aspirations for the future of Shropshire and in particular the parts that you know well. Meeting Shropshire’s development needs This consultation will shape the second Development Plan Document of the Shropshire Local Development Framework. It will identify sites and detailed policies to implement the first DPD, the Core Strategy. The Core Strategy sets out Shropshire’s development needs for the period 2006- 2026. To provide sufficient housing for our changing needs, we require around 27,500 new homes, plus up to 1,000 homes in eastern Shropshire to meet the needs of servicemen and women and about 113 caravan pitches for gypsies and travellers. To ensure a vibrant economy we need up to 290 hectares of land for employment development, provision for retail and town centre uses, and sites for sand and gravel quarrying. -

Church Preen Primary School Church Preen, Church Stretton, Shropshire SY6 7LH

School report Church Preen Primary School Church Preen, Church Stretton, Shropshire SY6 7LH Inspection dates 4–5 May 2016 Overall effectiveness Outstanding Effectiveness of leadership and management Outstanding Quality of teaching, learning and assessment Outstanding Personal development, behaviour and welfare Outstanding Outcomes for pupils Outstanding Early years provision Outstanding Overall effectiveness at previous inspection Requires improvement Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is an outstanding school The headteacher’s ambitious vision, knowledge Pupils’ behaviour and attitudes make them and willingness to learn are characteristics of his excellent ambassadors for the school. They are success in rapidly turning the school around. rightly proud to be pupils at Church Preen. Teachers and teaching assistants work tirelessly to Pupils are encouraged to take an active part in the plan inspiring lessons which provide pupils with life of the school. For example, older pupils enjoy exciting opportunities for learning. planning, organising and delivering new games for All pupils achieve well, including the most able and the younger ones. those who have special educational needs or Highly effective use is made of additional disability. Standards at the end of each key stage government funding to successfully close the gap are above average. in achievement between the disadvantaged pupils Teachers closely observe and record each small and other pupils nationally and in school. step of pupils’ progress and plan lessons to ensure All subjects are covered in impressive breadth and the rapid progress of all pupils, regardless of their depth. However, pupils do not consistently pay age or ability. sufficient attention to spelling, punctuation and Governors carry out their duties conscientiously. -

A9: Drainage and Wastewater Management Plan 2018

A9: Drainage and Wastewater Management Plan 2018 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Future pressures 4 3. Approach – planning for the future 5 4. Our planning tools 6 5. Defining our planning boundaries 8 6. Risk based catchment screening 10 7. Conclusion and next steps 18 APPENDICES A Strategic Planning Areas 20 B Tactical Planning Areas 109 C Catchment Plans 150 2 1.0 INTRODUCTION We are developing our first Drainage and Wastewater Management Plan Every day we drain over 2.7 billion litres of wastewater from our customers’ properties. We then treat this water at our wastewater treatment work before returning the cleaned water back to the environment. Our wastewater system consists of over 94,000km of sewers and drains, 4400 pumping stations and 1010 treatment works. This system has to continue to operate effectively day in day out but also needs to be able to cope with future pressures and this is where our Drainage and Wastewater Management Plan comes in. Our Drainage and Wastewater Management Plan will cover the investments we plan to make over the next 5 year period, 2020 to 2025, as well setting out a long term (25 year) strategy for how we are going to deliver a reliable and sustainable wastewater service. The first full publication of Drainage and Wastewater Management Plans (DWMPs) is not scheduled until 2022/23. We have chosen to provide a draft of our initial findings to: support the strategic investments we are proposing for AMP7; demonstrate our commitment to long term, sustainable, wastewater planning; and, provide an early benchmark to support and encourage the sector in development of DWMPs - in keeping with our position as a sector leader and innovator. -

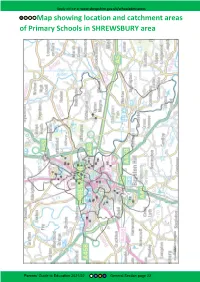

Map Showing Location and Catchment Areas of Primary Schools in SHREWSBURY Area

Apply online at www.shropshire.gov.uk/schooladmissions Map showing location and catchment areas of Primary Schools in SHREWSBURY area 21/22 General Section page 22 Apply online at www.shropshire.gov.uk/schooladmissions C - Community F - Foundation List of PRIMARY Schools FS - Free School VC - Voluntary Controlled On the following pages, data is provided to show the number of first VA - Voluntary Aided A - Academy preferences received by 16 April 2020 for each school. Where the school was oversubscribed, the admissions criteria of the last person allocated on 16 April 2020 is shown. This relates to the relevant admissions policy priority; either page 12 pages 15-21). The distance given (in miles) is the cut-off point of the furthest applicant eligible for a place in that category as at 16 April 2020. SHREWSBURY AREA School name and address School DfE Headteacher, Number Age PAN 1st Pref No telephone number of Pupils Range received and web address at Jan 20 16 Apr 2020 1 Belvidere Primary 2164 Mr A Davis 236 3-11 34 34 Tenbury Drive, Telford Estate, 01743 365211 Shrewsbury SY2 5YB C www.belvidere-pri.shropshire.sch.uk/ Apr 20: Priority 4b 1.529 miles 2 Coleham Primary 2084 Ms C Jones 423 5-11 60 78 Greyfriars Road, 01743 362668 Shrewsbury SY3 7EN A www.colehamprimary.co.uk Apr 20: Priority 5 0.627 miles 3 Crowmoor Primary & Nursery 2088 Mr A J Parkhurst 192 4-11 30 18 Crowmere Road, 01743 235549 Shrewsbury SY2 5JJ F http://crowmoorschool.co.uk/ 4 Grange Primary and Nursery 2001 Mrs C Summers 210 3-11 60 18 Bainbridge Green, York Road, 01743