THE TURNPIKE ROADS of HIGH LITTLETON and HALLATROW The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

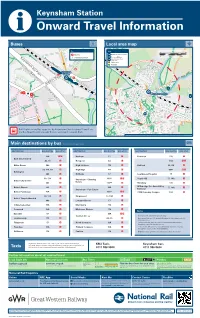

Keynsham Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Keynsham Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map Key Key km 0 0.5 A Bus Stop LC Keynsham Leisure Centre 0 Miles 0.25 Station Entrance/Exit M Portavon Marinas Avon Valley Adventure & WP Wildlife Park istance alking d Cycle routes tes w inu 0 m Footpaths 1 B Keynsham C Station A A bb ey Pa r k M D Keynsham Station E WP LC 1 1 0 0 m m i i n n u u t t e e s s w w a a l l k k i i n n g g d d i i e e s s t t c c a a n n Rail Replacement Bus stops are by Keynsham Church (stops D and E on the Bus Map) Stop D towards Bristol, and stop E towards Bath. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at October 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP 19A A E Hanham 17 C Radstock 178 E Bath City Centre ^ A4, 39 E Hengrove A4 D 19A A E Bilbie Green 349 D High Littleton 178 E Saltford 39, A4 E 39, 178, A4 D Highridge A4 D 664* B E Brislington 349 E Hillfields 17 C Southmead Hospital 17 C 39, 178 D 663* B E Staple Hill 17, 19A C Keynsham - Chandag Bristol City Centre Estate 349 E 178** E Timsbury 178 E Willsbridge (for Avon Valley Bristol Airport A4 D 349 E 17, 19A C Keynsham - Park Estate Railway) Bristol Parkway ^ 19A C 665* B E UWE Frenchay Campus 19A C 39, 178 D Kingswood 17, 19A C Bristol Temple Meads ^ 349 E Longwell Green 17 C Cribbs Causeway 19A C Marksbury 178 E Downend 19A C Midsomer Norton 178 E Notes Eastville 17 C 19A A E Newton St Loe Bus routes 17, 39 and A4 operate daily. -

Notfoprint21.Pdf

2011 Lake Odyssey was a Heritage Lottery Funded project exploring local history through the arts with a particular focus on the 1950’s, when Chew Valley Lake was made. This was a major local event. The town of Moreton was fl ooded to make way for a reservoir supplying water to South Bristol and the Queen visited the area to offi cially open and inaugurate the lake in 1956. The Lake Odyssey 2011 project gave pupils at Chew Valley School and their cluster of primary schools a chance to explore the history of their community in a fun and creative way. Pupils took part in various workshops throughout the spring and summer of 2011 to produce the content for the fi nal Lake Odyssey event day on Saturday 16th July 2011, which saw the local community come together for a day of celebration and performance at Chew Valley Lake. Balloon Launch The Lake Odyssey 2011 project offi cially launched on Friday 4th March with a balloon re- lease. Year seven and eight pupils released the balloons to mark and celebrate the occasion. A logo competition had been running within the primary cluster and Chew Valley School to fi nd a design for the Lake Odyssey logo. The winners were announced by Heritage Lottery representative Cherry Ann Knott. The lucky winners were Bea Tucker from East Harptree Pri- mary School and Hazel Stockwell-Cooke from Chew Valley School, whose designs featured in all publicity for the Lake Odyssey 2011 project. Bishop Sutton Songwriting Swallow class from Bishop Sutton Primary School took part in a song writing workshop, com- posing their own song from scratch with Leo Holloway. -

Documents D – E (Part 2) Download

Appendix E 13 14 T( ) Y A W R Existing Cycleway O T O Proposed Cycleway M 2 3 M Widening of carriageway to facilitate creation of Junction 1 Existing footway improved to new southbound cycle lane a shared-surface foot/cycleway Cycle/pedestrian improvements at signal junction Appendix E M32 Southbound Slip Road Proposed toucan crossing Appendix E N 10 Y Existing off road cycle route Existing on road cycle route Planned cycle scheme Cycle Ambition grant bid 4C Scheme reference TADWICK Bath ‘City of Ideas’ Enterprise Area K1 LANGRIDGE SOMERDALE STOCKWOOD NORTH K1 Cycle Scheme reference VALE STOKE STOCKWOOD NCN4 LANSDOWN WOOLLEY Kennet & Avon SHOCKERWICK UPPER NORTHEND 20 20mph speed limit in residential areas SWAINSWICK 20 Cycle Route S1 UPPER QUEEN K2 WESTON LOWER CHARLTON Keynsham KELSTON Bath BAILBROOK CHEWTON KEYNSHAM WESTON 20 PRIMROSE B1 WESTON HILL PARK 20 SION HILL NEWBRIDGE BLACKROCK BURNETT NORTON LOWER MALREWARD WESTON NCN4 BATHWICK NORTON EAST HAWKFIELD TWERTON PRIEST COMPTON NEWTON U1 DOWN ST LOE KINGSMEAD WOOLLARD COMPTON GREEN Bristol Bath DANDO TWERTON PUBLOW BEECHEN CLIFF WIDCOMBE Railway Path WHITEWAY SOUTH LYNCOMBE PENSFORD TWERTON BEAR HILL LITTLETON FLAT THE MOORLANDS TWERTON OVAL LYNCOMBE HILL SOUTHDOWN VALE PERRYMEAD KINGSWAY UPPER U2 CHEW MAGNA STANTON PADLEIGH FOX BLOOMFIELD STANTON DREW STANTON ENGLISHCOMBE HILL DREW WHITLEY PRIOR HUNSTRETE RUSH BATTS HILL MARKSBURY MOORLEDGE CHELWOOD ODD COMBE DOWN MONKTON STANTON DOWN CHEW STOKE WICK COMBE NEWTOWN INGLESBATCH NCN244SOUTH STOKE LIMPLEY NAILWELL Two Tunnels MIDFORD -

Tickets Are Accepted but Not Sold on This Service

May 2015 Guide to Bus Route Frequencies Route Frequency (minutes/journeys) Route Frequency (minutes/journeys) No. Route Description / Days of Operation Operator Mon-Sat (day) Eves Suns No. Route Description / Days of Operation Operator Mon-Sat (day) Eves Suns 21 Musgrove Park Hospital , Taunton (Bus Station), Monkton Heathfield, North Petherton, Bridgwater, Dunball, Huntspill, BS 30 1-2 jnys 60 626 Wotton-under-Edge, Kingswood, Charfield, Leyhill, Cromhall, Rangeworthy, Frampton Cotterell, Winterbourne, Frenchay, SS 1 return jny Highbridge, Burnham-on-Sea, Brean, Lympsham, Uphill, Weston-super-Mare Daily Early morning/early evening journeys (early evening) Broadmead, Bristol Monday to Friday (Mon-Fri) start from/terminate at Bridgwater. Avonrider and WestonRider tickets are accepted but not sold on this service. 634 Tormarton, Hinton, Dyrham, Doyton, Wick, Bridgeyate, Kingswood Infrequent WS 2 jnys (M, W, F) – – One Ticket... 21 Lulsgate Bottom, Felton, Winford, Bedminster, Bristol Temple Meads, Bristol City Centre Monday to Friday FW 2 jnys –– 1 jny (Tu, Th) (Mon-Fri) 635 Marshfield, Colerne, Ford, Biddestone, Chippenham Monday to Friday FS 2-3 jnys –– Any Bus*... 26 Weston-super-Mare , Locking, Banwell, Sandford, Winscombe, Axbridge, Cheddar, Draycott, Haybridge, WB 60 –– (Mon-Fri) Wells (Bus Station) Monday to Saturday 640 Bishop Sutton, Chew Stoke, Chew Magna, Stanton Drew, Stanton Wick, Pensford, Publow, Woollard, Compton Dando, SB 1 jny (Fri) –– All Day! 35 Bristol Broad Quay, Redfield, Kingswood, Wick, Marshfield Monday to Saturday -

A Countryside New Year Getaway at Folly Farm Farmhouse-Style Accommodation Sleeping up to 46 Guests

A Countryside New Year Getaway at Folly Farm Farmhouse-style accommodation sleeping up to 46 guests Fresh air, stunning views and peaceful seclusion in the heart of Somerset Celebrate the arrival of 2019 with a unique countryside break with your loved ones at Folly Farm, a charmingly restored, environmentally sustainable 18th century farmhouse, hidden within a 250 acre Somerset nature reserve. Folly Farm could be exclusively-yours; a home- away-from-home with everything you need for a truly memorable New Year getaway with your nearest and dearest. The Farmhouse – 10 bedrooms Sleeping up to 26 guests, The Farmhouse offers comfortable country-style accommodation with all bedrooms leading off from the central atrium, complete with comfy sofas, a real log fire and a glass ceiling, perfect for star gazing with a glass of Champagne (or mug of hot chocolate) in hand. Within The Farmhouse there is also a professional kitchen available for guests to use, and the adjacent ‘Old Diary’ dining room (pictured) is ideal for group dining. Alternatively, our caterers can create bespoke New Year dining packages for your group – see below Catering section for more information. The Studios – 10 bedrooms Offering further accommodation for an additional 20 guests, the self-contained studio cottages are located just a stone’s throw from the Farmhouse with stunning views over Chew Valley Lake, the Mendip Hills and beyond. W: follyfarm.org.uk T: 01275 331 590 E: [email protected] A: The Folly Farm Centre, Stowey, Pensford, Bristol, BS39 4DW Catering (optional) Our rural location means delicious seasonal produce is in abundance and is often sourced from our very own kitchen garden. -

2017 May June Issue.Indd

MAY & JUNE 2017 Published on behalf of High Littleton Parish Council News & Views Clubs & Organisations News from the Parish Council Editor: Karen George High Littleton Beaver Scouts – Contact:- Ex-Vice Chairman Mr Bob Hitchens has resigned as Councillor of the High Littleton [email protected] Tricia Horwood Tel: 01761 470809 To advertise contact Vicki Smith 07815 620247 [email protected] Parish Council after nearly 20 years of service. Mr Hitchens was a highly valued Copy deadline for July / Aug 2017 issue: High Littleton Scout Group Contact:- Councillor whose vast contributions had included work towards the High Littleton 1/6/2017 Simon Walker [email protected] Pictorial History and the accounting system that is still being used. His historical Schools High Littleton with Farmborough Brownies knowledge and experience of the functioning of the High Littleton Parish Council and Contact:- Ann Edwards Tel: 07989 630541 the Local Government will leave a notable space. Mr R Hitchens will be missed. High Littleton Pre School – Tel: 07971 914659 [email protected] [email protected] High Littleton Toddler Group The Neighbourhood Plan is making excellent progress and has been going for 5 months. High Littleton C of E Primary School Contact:- Becky Fulford Tel: 01761 470410. The Steering Group is awaiting the results of a Landscape Assessment. The Council wish Tel:- 01761 470622 High Littleton Bell Ringing – Contact: - to thank all those on the Steering Group and parishioners for their input. offi [email protected] Jenny Cornwell. Tel: 01761 453641 Norton Hill School – Tel: 01761 412557 [email protected] The Council have employed Mr Simon Conway to design a new website for the Parish [email protected] High Littleton & Hallatrow Village Day Council. -

FRACKING in NORTH-EAST SOMERSET HOW MANY WELLS and WHERE MIGHT THEY BE? the Present Government Is Keen to Promote an American St

FRACKING IN NORTH-EAST SOMERSET HOW MANY WELLS AND WHERE MIGHT THEY BE? The present government is keen to promote an American style unconventional gas revolution in Britain. This could mean big industry moving into our neighbourhood with the attendant disruption, potential risks, and effect on house prices. Parts of Somerset have been licensed for exploration and development. Industry interest has focused primarily on coalbed methane (CBM) with shale gas as a secondary possibility. Fracking may be used for both. Extraction of CBM is likely to be occur much nearer the surface than shale. How many wells & where? In 2000 the American CBM company GeoMet Inc.evaluated the CBM potential of the 400 km2 area shown in Fig. 1 Its report was retrieved from publicly available sources by Frack Free Chew Valley (FFCV) and is available with a detailed commentary. [Coalbed Methane Exploration in Somerset, the Chew Valley, Keynsham & the Mendip Hills https://frackfreecv.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/unconventionalgasexplorationinsomerset_160614b.pd f ] Most of the information here comes from that report where full detail and references should be sought. In its 2000 assessment GeoMet decided to concentrate on areas with coal measures at optimum depth , shown in grey in Fig. 1, and to exclude urban areas and areas where the coal had been previously worked. There seems to be no reason why CBM might not be extracted from other coal seams, but it appears that GeoMet first concentrated on the least complicated areas. This "developable" area, 108 km2 , GeoMet stated, could "accommodate" about 300 gas wells. Fig. 1 gives an indication of their location, according to FFCV's assumption of even distribution. -

Sol\Fersetshire. EAST COK.ER

DIRECfORY.] SOl\fERSETSHIRE. EAST COK.ER. 205 has been completed: there are sittings for 140 persons: in years. The area is 1,046 acres; rateable value, £990; the the churchyard is an ancient cross and a tomb to Thomas population in 1891 was 112. Purdue, a bellfounder of repute, whose foundry stood where Parish Clerk, Benjamin Tomkins. is now the rector's orchard i he died in 17II· 'fbe register PosT 0FFICE.-Arthur Loveless, sub-postmaster. Letters dates from the year 1685. The living is a rectory, gross by mail cart from Sherborne, Dorset, arrive at 8.50 a.m.; yearly value £160, with residence and 21 acres of glebe, in dispatched at 4.45 p.m. week days only. Postal orders the gift of Viscount Portman, and held since 1876 by the are issued here, but not paid. Yetminster is the neare!;t Rev. John Algernon Lawrence LL.M. of Jesus College, Cam- money order & telegraph office, miles distant bridge. The only house of interest in the parish is the 3 rectory, which bears date 16o6. Viscount Portman is lord WALL LETTER Box, Prowse's cross, cleared at 5 p.m. week of the manor and sole landowner. The soil and subsoil are days only clay. The chief crops are wheat, oats and roots, but pasture Church School (mixed), built in 1871, for 40 children; land to a considerable extent has been laid down of recent average attendance, 15 ; Miss Margaret Holland, mistress Holland Miss Thring Thomas Charles Edward Tomkins Benj. farmer, & parish clerk Lawrence Rev. John Algernon M.A. -

Area 1: Thrubwell Farm Plateau

Area 1: Thrubwell Farm Plateau Summary of Landscape Character • Clipped hedges which are often ‘gappy’ and supplemented by sheep netting • Late 18th and early 19th century rectilinear field layout at north of area • Occasional groups of trees • Geologically complex • Well drained soils • Flat or very gently undulating plateau • A disused quarry • Parkland at Butcombe Court straddling the western boundary • Minor roads set out on a grid pattern • Settlement within the area consists of isolated farms and houses For detailed Character Area map see Appendix 3 23 Context Bristol airport on the plateau outside the area to the west. Introduction Land-uses 7.1.1 The character area consists of a little over 1sq 7.1.6 The land is mainly under pasture and is also km of high plateau to the far west of the area. The plateau used for silage making. There is some arable land towards extends beyond the Bath and North East Somerset boundary the north of the area. Part of Butcombe Court parkland into North Somerset and includes Felton Hill to the north falls within the area to the west of Thrubwell Lane. and Bristol airport to the west. The southern boundary is marked by the top of the scarp adjoining the undulating Fields, Boundaries and Trees and generally lower lying Chew Valley to the south. 7.1.7 Fields are enclosed by hedges that are generally Geology, Soils and Drainage trimmed and often contain few trees. Tall untrimmed hedges are less common. Hedges are typically ‘gappy’ and of low 7.1.2 Geologically the area is complex though on the species diversity and are often supplemented with sheep- ground this is not immediately apparent. -

Pensford September Mag 09

Industrial, Commercial and September 09 Domestic Scaffolding ● Quality Scaffolding ● Competitive Rates ● Safety Our Priority ● Very Reliable Service ● 7 Days / 24 Hours ● 20 Years Experience ● C.I.T.B Qualified Team of Erectors Bristol: 01179 649 000 Bath: 01225 334 222 Mendip: 01761 490 505 Head Office: Unit 3, Bakers Park, Cater Rd. Bristol. BS13 7TT United Benefice of Publow with Pensford, Compton Dando and Chelwood 20p UNITED BENEFICE OF PUBLOW WITH PENSFORD, COMPTON DANDO AND CHELWOOD Directory of Local Organisations Bath & North East Somerset Chelwood Mr R. Nicholl 01275 332122 Council ComptonDando Miss S. Davis 472356 Publow Mr P. Edwards 01275 892128 Assistant Priest: Revd Sue Stevens 490898 Bristol Airport (Noise Concerns) 01275 473799 Woollard Place, Woollard Chelwood Parish Council Chairman Mr P. Sherborne 490586 Chelwood Bridge Rotary Club Tony Quinn 490080 Compton Dando Parish Chairman Ms T. Mitchell 01179 860791 Reader: Mrs Noreen Busby 452939 Council Clerk Mrs D. Drury 01179 860552 Compton Dando CA Nan Young 490660 Churchwardens: Publow Parish Council Chairman Mr A.J Heaford 490271 Publow with Pensford: Miss Janet Ogilvie 490020 Clerk Mrs J. Bragg 01275 333549 Pensford School Headteacher Ms L. MAcIsaac 490470 Mrs Janet Smith 490584 Chair of Governors Mr B. Watson 490506 Compton Dando: Mr Clive Howarth 490644 Chelwood Village Hall Bookings Mr Pat Harrison 490218 Jenny Davis 490727 Compton Dando Parish Hall Bookings Mrs Fox 490955 Chelwood: Mrs Marge Godfrey 490949 Pensford Memorial Hall Chairman Terry Phillips 490426 Bookings -

ID Pensford Summer Mag 08.Pmd

July and August 08 Calling all Singers Pensford Tennis Club Dear Friends, Chew Valley Choral Society would like to Despite the awful weather we have been This is the magazine issue which covers two months, the sum- hear from any singers in the area who would experiencing, we have been playing a lot mer months, the warm sunny months - the time when many like to join us in September – whether so- on the courts – a good way to keep the prano, alto, tenor or bass. We do not require moss down! people have their holidays and the time when the children are auditions, but some choral experience is COACHING for Adults and children – we have not in school. helpful, as is the ability to read music. two very nice qualifi ed club coaches and you don’t have to be a club member to use their For Churches, this is the time for weddings and garden fetes, ABOUT US - We were formed in 1976 and meet weekly in Chew Stoke Church Hall services. If you would like coaching please for fl ower festivals and outdoor services. The sun brings out the for rehearsals leading to two concerts each contact Ron Grew (for adults) on 01761 smiles, the good times, but it also means the grass has to be cut year, usually in Chew Magna and Blagdon 472234 or Matt Thompson (for children) on Churches. Our music director is David Bed- 01275 891515 and the weeds seem to grow twice as fast as normal! nall, formerly with Wells Cathedral but now Club play is held on Tuesday evenings at However in some parts of the world the sun does not bring based in Bristol, where he is furthering a 7.00pm and Sunday mornings at 11am to 1.00pm. -

Core Strategy & Placemaking Plan

Bath and North East Somerset Local Plan 2011-2029 VOLUME: CORE STRATEGY & PLACEMAKING PLAN Rural 5 Areas Core Strategy Placemaking Plan Adopted July 2014 Adopted July 2017 CONTENTS 2 RURAL AREAS 31 FARMBOROUGH 2 Context 33 FARRINGTON GURNEY 4 Strategic Issues 35 HIGH LITTLETON & HALLATROW 4 Vision and Policy Framework – The Vision for the Rural Areas 5 Policy Framework 37 HINTON BLEWETT 5 Background 39 SALTFORD 5 Local Green Space Designations 41 STOWEY SUTTON – BISHOP SUTTON 7 BATHAMPTON 43 TIMSBURY 44 SR14 – Wheelers Manufacturing Block Works Context 9 BATHEASTON 45 Policy SR14 Development Requirements and Design Principles 11 BATHFORD 46 SR15 – Land to the East of the St Mary’s School Context 13 CAMELEY & TEMPLE CLOUD 47 Policy SR15 Development Requirements and Design Principles 14 SR24 – Land adjacent to Temple Inn Lane Context 15 Policy SR24 – Development Requirements and Design Principles 49 UBLEY 51 WEST HARPTREE 17 CAMERTON 52 SR2 – Leafield Context 19 CLUTTON 52 SR2 – Leafield: Vision for the site 21 COMPTON MARTIN 53 Policy SR2 – Development Requirements and Design Principles 22 SR17 – The Former Orchard Context 55 WHITCHURCH 23 Policy SR17 – Development Requirements and Design Principles 57 Policy RA5 – Land at Whitchurch Strategic Site Allocation 25 EAST HARPTREE 26 SR5 – Pinkers Farm Context 27 Policy SR5 – Development Requirements and Design Principles 28 SR6 – Water Street Context 29 Policy SR6 – Development Requirements and Design Principles FORMAT NOTE The Local Plan 2011-2029 comprises two separate Development Plan Documents: the Core Strategy (adopted July 2014) and the Placemaking Plan (adopted July 2017). Core Strategy policies and strategic objectives are shown with a light yellow background and Placemaking Plan policies are shown with a light blue background.