Revisiting Tolman, His Theories and Cognitive Maps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operant Conditioning

Links to Learning Objectives DEFINITION OF LEARNING OPERANT CONDITIONING (Part 2) LO 5.1 Learning LO 5.8 Controlling behavior and resistance LO 5.9 Behavior modification CLASSICAL CONDITIONING LO 5.2 Study of and important elements COGNITIVE LEARNING LO 5.3 Conditioned emotional response LO 5.10 Latent learning, helplessness and insight OPERANT CONDITIONING (Part 1) LO 5.4 Operant, Skinner and Thorndike OBSERVATIONAL LEARNING LO 5.5 Important concepts LO 5.11 Observational learning theory LO 5.6 Punishment problems LO 5.7 Reinforcement schedules Learning Classical Emotions Operant Reinforce Punish Schedules Control Modify Cognitive Helpless Insight Observe Elements Operant Conditioning Operant Stimuli Behavior 5.8 How do operant stimuli control behavior? • Discriminative stimulus –cue to specific response for reinforcement Learning Classical Emotions Operant Reinforce Punish Schedules Control Modify Cognitive Helpless Insight Observe Elements 1 Biological Constraints • Instinctive drift – animal’s conditioned behavior reverts to genetic patterns – e.g., raccoon washing, pig rooting Learning Classical Emotions Operant Reinforce Punish Schedules Control Modify Cognitive Helpless Insight Observe Elements ehavior modification Application of operant conditioning to effect change Behavior Modification 5.9 What is behavior modification? • Use of operant techniques to change behavior Tokens Time out Applied Behavior Analysis Learning Classical Emotions Operant Reinforce Punish Schedules Control Modify Cognitive Helpless Insight Observe Elements -

Operant Conditioning and Pigs

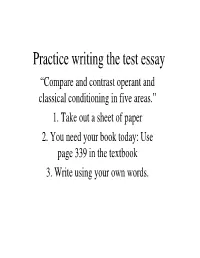

Practice writing the test essay “Compare and contrast operant and classical conditioning in five areas.” 1. Take out a sheet of paper 2. You need your book today: Use page 339 in the textbook 3. Write using your own words. Exchange papers • Peer edit their paper. • Check to see if they have the needed terms and concepts. • If they don’t add them. • If they do give them a plus sign (+) • Answers in red Essay note • You won’t be able to use your notes or book on Monday’s test. .∑¨π®µªΩ∫ "≥®∫∫∞™®≥"∂µ´∞ª∞∂µ∞µÆ Remembering the five categories • B • R • A • C • E B • Biological predispositions "≥®∫∫∞™®≥ ™∂µ´∞ª∞∂µ∞µÆ©∞∂≥∂Æ∞™®≥ /π¨´∞∫∑∂∫∞ª∞∂µ∫ ≥¨®πµ∞µÆ∞∫™∂µ∫ªπ®∞µ¨´©¿®µ®µ∞¥ ®≥∫©∞∂≥∂Æ¿ µ®ªºπ®≥∑π¨´∞∫∑∂∫∞ª∞∂µ∫™∂µ∫ªπ®∞µ∫∂π≥∞¥ ∞ª∫ æ Ø®ª∫ª∞¥ º≥∞®µ´π¨∫∑∂µ∫¨∫™®µ©¨®∫∫∂™∞®ª¨´ ©¿ªØ¨®µ∞¥ ®≥ John Garcia’s research, 322 • Biological predispositions • John Garcia: animals can learn to avoid a drink that will make them sick, but not when its announced by a noise or a light; !≥∂Æ∞™®≥/π¨´∞∫∑∂∫∞ª∞∂µ∫ C o u r t e s & ®π™∞®∫Ø∂æ ¨´ªØ®ªª ¨´ºπ®ª∞∂µ y o f J o ©¨ªæ ¨¨µª ¨"2®µ´ªØ¨4 2¥ ®¿©¨ h n G a r ≥∂µÆ&Ø∂ºπ∫'©ºª¿¨ªπ¨∫º≥ª∞µ c i a ™∂µ´∞ª∞∂µ∞µÆ ©∞∂≥∂Æ∞™®≥≥¿®´®∑ª∞Ω¨ )∂ص& ®π™∞® "2&ª®∫ª¨'≥¨´ª∂™∂µ´∞ª∞∂µ∞µÆ®µ´µ∂ª ª∂∂ªØ¨π∫&≥∞Æت∂π∫∂ºµ´' Human example • We more easily are classically conditioned to fear snakes or spiders, rather than flowers. -

Edward C. Tolman (1886-1959)

Edward C. Tolman (1886-1959) Chapter 12 1 Edward C. Tolman 1. Born (1886) in West Newton, Massachusetts. 2. B.S from MIT. PhD from Harvard. 3. Studied under Koffka. 4. 1915-1918 taught at www.uned.es Northwestern University. Released from university. Pacifism! (1886-1959) 2 Edward C. Tolman 5. Moved to University of California-Berkeley and remained till retirement. 6. Dismissed from his position for not signing the “loyalty oath”. Fought for academic freedom and www.uned.es reinstated. 7. Quaker background (1886-1959) therefore hated war. Rebel in life and psychology. 3 1 Edward C. Tolman 8. Did not believe in the unit of behavior pursued by Pavlov, Guthrie, Skinner and Hull. “Twitchism” vs. molar behavior. 9. Learning theory a blend of Gestalt psychology and www.uned.es behaviorism. 10. Died 19 Nov. 1959. (1886-1959) 4 Comparison of Schools Behaviorism Gestalt Gestalt psychologists Behaviorists believed believed in the in “elements” of S-R “whole” mind or associations. mental processes. Observation, Observation and Experimentation and Experimentation Introspection Approach: Behavioral Approach: Cognitive 5 Tolman’s idea about behavior 1. Conventional behaviorists do not explain phenomena like knowledge, thinking, planning, inference, intention and purpose in animals. In fact, they do not believe in mental phenomena like these. 2. Tolman on the other hand describes animal behavior in all of these terms and takes a “Gestalt” viewpoint on behavior, which is to look at behavior in molar or holistic terms. 6 2 Tolman’s idea about behavior 3. So rat running a maze, cat escaping the puzzle box and a man talking on the phone are all molar behaviors. -

14 Learning, I: the Acquisition of Knowledge

14 LEARNING, I: THE ACQUISITION OF KNOWLEDGE Most animals are small and don’t live long; flies, fleas, protists, nematodes and similar small creatures comprise most of the fauna of the planet. A small animal with short life span has little reason to evolve much learning ability. Because it is small, it can have little of the complex neu- ral apparatus needed; because it is short-lived it has little time to exploit what it learns. Life is a tradeoff between spending time and energy learning new things, and exploiting things already known. The longer an animal’s life span, and the more varied its niche, the more worthwhile it is to spend time learning.1 It is no surprise; therefore, that learning plays a rather small part in the lives of most ani- mals. Learning is not central to the study of behavior, as was at one time believed. Learning is interesting for other reasons: it is involved in most behavior we would call intelligent, and it is central to the behavior of people. “Learning”, like “memory”, is a concept with no generally agreed meaning. Learning cannot be directly observed because it represents a change in an animal’s potential. We say that an animal has learned something when it behaves differently now because of some earlier ex- perience. Learning is also situation-specific: the animal behaves differently in some situations, but not in others. Hence, a conclusion about whether or not an animal has learned is valid only for the range of situations in which some test for learning has been applied. -

AP Psychology Essential Information

AP Psychology Essential Information Introduction to Psychology 1. What is the definition of psychology? a. The study of behavior and mental processes 2. How did psychology as a study of behavior and mental processes develop? a. The roots of psychology can be traced back to the philosophy of Empiricism: emphasizing the role of experience and evidence, especially sensory perception, in the formation of ideas, while discounting the notion of innate ideas.- Greeks like Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. Later studied by Francis Bacon, Rene Decartes and John Locke. 3. What is the historical development of psychology? a. The evolution of psychology includes structuralism, functionalism, psychoanalysis, behaviorism and Gestalt psychology b. Wilhelm Wundt: set up the first psychological laboratory. i. trained subjects in introspection: examine your own cognitive processing- known as structuralism ii. study the role of consciousness; changes from philosophy to a science ii. Also used by Edward Titchener c. William James: published first psychology textbook; examined how the structures identified by Wundt function in our lives- functionalism i. Based off of Darwin’s theory of evolution 4. What are the different approaches to studying behavior and mental processes? a. biological, evolutionary, psychoanalysis (Freud), behavioral (Watson, Ivan Pavlov, B.F. Skinner), cognitive, humanistic (Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers), social (Bandura) and Gestalt 5. Who are the individuals associated with different approaches to psychology? a. Darwin, Freud, Watson, Skinner and Maslow 6. What are each of the subfields within psychology? a. cognitive, biological, personality, developmental, quantitative, clinical, counseling, psychiatry, community, educational, school, social, industrial Methods and Testing 1. What are the two main forms of research? a. -

The General Psychological Crisis and Its Comparative Psychological Resolution

eScholarship International Journal of Comparative Psychology Title The General Psychological Crisis and its Comparative Psychological Resolution Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2g60z086 Journal International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2(3) ISSN 0889-3675 Author Tolman, Charles W. Publication Date 1989 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The International Journal of Comparative Psychology, Vol. 2, No. 3, Spring 1989 THE GENERAL PSYCHOLOGICAL CRISIS AND ITS COMPARATIVE PSYCHOLOGICAL RESOLUTION Charles W. Tolman University of Victoria ABSTRACT: The crisis in general psychology is identified as one of theoretical indeter- minacy. An important source of indeterminacy is the form of generalization that empha- sizes classification and common characters and identifies the general with the abstract. Determinate theory requires a form of generalization that identifies the general with the concrete and emphasizes genesis and interconnection. In order to overcome its crisis, general psychology thus requires the kind of evolutionary methodology that comparative psychology is, historically speaking, best prepared to provide. Science must begin w^ith that w^ith which real history began. Logical devel- opment of theoretical definitions must therefore express the concrete historical process of the emergence and development of the object. Logical deduction is nothing but a theoretical expression of a real historical development of the concreteness under study. (Ilyenkov, 1982, p. 200) The decade of the 1970s w^as a difficult period for comparative psychology. The troubles first became apparent somewhere around 1950 M^hen Frank Beach called attention, in a deploring tone, to our "excessive concentration" on a very limited number of species, especially the ubiq- uitous Rattus norvegicus. -

IAABC Core Competencies

IAABC Core Competencies The IAABC recommends animal behavior consultants be skilled in seven Core Areas of Competency: I. Assessment Skills II. General Knowledge and Application of Learning Science III. Species-Specific Knowledge IV. Consulting Skills V. General Knowledge of Animal Behavior VI. Biological Sciences as Related to Animal Behavior VII. Ethics Core competency is defined as “a skill needed in order to be successful at a job or other activity.”[1] Success as an animal behavior consultant depends on the ability of the consultant to accurately assess the function of an animal’s behavior, and implement effective behavior modification strategies in agreement with a Least-Intrusive, Minimally Aversive approach. Animal behavior consultants also should maintain a working knowledge of biology as it relates to animal behavior, an understanding of consulting and behavior change program management, and ethics as it relates to both animal behavior and human learning. I) ASSESSMENT SKILLS A. History taking skills and history assessment 1. Eliciting accurate information 2. Interpretation of information provided 3. Assessing owner interpretation of behavioral issues B. Behavioral observation skills 1. Accurate observation and interpretation of behaviors demonstrated by the animal 2. Ability to integrate information obtained by direct observation of the animal and the humans involved C. Apply and integrate any additional behavioral, historical, medical and physiologic information. © IAABC. All Rights Reserved. | www.iaabc.org 1 1. Critically evaluate the quality of this information. 2. Act appropriately to remedy any areas of concern II) GENERAL KNOWLEDGE AND APPLICATION OF LEARNING SCIENCE A. Learning Science 1. Operant conditioning 2. Classical conditioning 3. Desensitization 4. -

Associative Learning in Honey Bees R Menzel

Associative learning in honey bees R Menzel To cite this version: R Menzel. Associative learning in honey bees. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 1993, 24 (3), pp.157-168. hal-00891068 HAL Id: hal-00891068 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00891068 Submitted on 1 Jan 1993 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Review article Associative learning in honey bees R Menzel Freie Universität Berlin, Fachbereich Biologie, Institut für Neurobiologie, Königin-Luise-Straße 28-30, 1000 Berlin 33, Germany (Received 20 October 1992; accepted 9 February 1993) Summary — The learning behavior of honey bees has been reviewed. In the context of foraging be havior, bees perform 2 forms of learning, latent (or observatory) and associative learning. Latent learning plays an important role in spatial orientation and learning during dance communication, but the mechanisms of this kind of learning are little understood. In associative learning, stimuli experi- enced immediately before the reward (usually sucrose solution) are memorized for the guidance of future behavior. Well-established paradigms have been used to characterize operant and classical conditioning. The classical conditioning of olfactory stimuli is a very effective form of learning in bees and has helped to describe the behavioral and physiological basis of memory formation. -

Latent Learning As a Function of Exploration Time Gary France Central Washington University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at Central Washington University Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1965 Latent Learning as a Function of Exploration Time Gary France Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Educational Psychology Commons, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons Recommended Citation France, Gary, "Latent Learning as a Function of Exploration Time" (1965). All Master's Theses. Paper 477. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. ~.-- ·• .C.· '.'>:'*'~ LATENT LEARNING AS A FUNCTION OF EXPLORATION Til~E A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Master of Science in Psychology by Gary France August 1965 LD 5771.3 rf)I 5 /.J ;:; ,·.·· cc«.~.:,>, . :; T 7 APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ________________________________ J. J. Crawford, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN _________________________________ Thomas B. Collins, Jr. _________________________________ Gerald Gage TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Latent Learning as a Function of Exploration Time 1 Five Types of Latent-Learning Experiments . 5 Type 1 • • • • • • . • • • . 5 Type 2 • • • • • • • . • . 7 Type 3 . 8 Type 4 . 9 Type 5 . 10 Seward's 1949 Study • . 13 The Problem . 17 Learning without reinforcement . 17 Control Seward's 1949 Study • . 18 'Misinforming' the rats • • • • • • 18 Test Croake's study •••••••• 19 Hypothesis . -

Spatial Learning: Conditions and Basic Effects V.D

Psicológica (2002), 23, 33-57. Spatial Learning: Conditions and Basic Effects V.D. Chamizo* Universitat de Barcelona A growing body of evidence suggests that the spatial and the temporal domains seem to share the same or similar conditions, basic effects, and mechanisms. The blocking, unblocking and overshadowing experiments (and also those of latent inhibition and perceptual learning reviewed by Prados and Redhead in this issue) show that to exclude associative learning as a basic mechanism responsible for spatial learning is quite inappropriate. All these results, especially those obtained with strictly spatial tasks, seem inconsistent with O’Keefe and Nadel’s account of true spatial learning or locale learning. Their theory claims that this kind of learning is fundamentally different and develops with total independence from other ways of learning (like classical and instrumental conditioning -taxon learning). In fact, the results reviewed can be explained appealing on to a sophisticated guidance system, like for example the one proposed by Leonard and McNaughton (1990; see also McNaughton and cols, 1996). Such a system would allow that an animal generates new space information: given the distance and address from of A to B and from A to C, being able to infer the distance and the address from B to C, even when C is invisible from B (see Chapuis and Varlet, 1987 -the contribution by McLaren in this issue constitutes a good example of a sophisticated guidance system). 1. Introduction. Are both the “when to respond” problem and the “where to respond” one governed by the same, general associative laws? Or are they not? To debate the idea of a general learning mechanism is not new. -

Major Theories & Research Studies in Psychology

Major Theorists & Research Studies in Psychology From Joe Cravens, Dr. Phillips High School Rene Descartes: Dualism (mind and body are separate entities) John Locke: Tabula Rasa Theory (you were born a blank slate) Wilhelm Wundt: Father of modern psychology / introspection to study structuralism / selective attention / voluntarism = we control our attention, which in turn effects other psychological processes (memory, thought, perceptions) William James: America’s first psychologist / first psych textbook / functionalism Ivan Pavlov: Dogs and the salivary response / classical conditioning / Does his name ring a bell? Psychoanalytic / Psychodynamic Sigmund Freud: This is your unconscious not speaking to you / Id, Ego, Superego, stages of psychosexual development; oral, anal, phallic, latent, and genital / libido / transference Alfred Adler: Are you compensating for your inferiority complex? / Birth order / proposed that people are motivated more by feelings of inferiority than sexual instincts / are you ‘compensating’ for something? Anna Freud: Are your Ego Defense mechanisms working? Hermann Rorschach: Inkblots as projective tests Karen Horney: Feminist’s perspective with womb envy Henry Murray: Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) / the need for achievement Carl Gustav Jung: collective unconscious / mandala / archetypes / rational individuals – are people who regulate their actions by the psychological functions of thinking and feeling / irrational individuals are people who base their actions on perceptions, either through the senses (sensation) or through unconscious processes (intuition). Anima = female archetype as expressed in the male personality, animus = male archetype as expressed in the female personality. Introverts vs. extraverts. Erik Erikson: The stages of Psychosocial Development / adolescent identity crisis / lifespan development James Marcia: Identity Status (based on the work of Erikson) Identity Diffusion – the adolescent has not yet experienced a crisis or made any commitments. -

A Critical Companion to Zoosemiotics BIOSEMIOTICS

A Critical Companion to Zoosemiotics BIOSEMIOTICS VOLUME 5 Series Editors Marcello Barbieri Professor of Embryology University of Ferrara, Italy President Italian Association for Theoretical Biology Editor-in-Chief Biosemiotics Jesper Hoffmeyer Associate Professor in Biochemistry University of Copenhagen President International Society for Biosemiotic Studies Aims and Scope of the Series Combining research approaches from biology, philosophy and linguistics, the emerging field of biosemi- otics proposes that animals, plants and single cells all engage insemiosis – the conversion of physical signals into conventional signs. This has important implications and applications for issues ranging from natural selection to animal behaviour and human psychology, leaving biosemiotics at the cutting edge of the research on the fundamentals of life. The Springer book series Biosemiotics draws together contributions from leading players in international biosemiotics, producing an unparalleled series that will appeal to all those interested in the origins and evolution of life, including molecular and evolutionary biologists, ecologists, anthropologists, psychol- ogists, philosophers and historians of science, linguists, semioticians and researchers in artificial life, information theory and communication technology. For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/7710 Dario Martinelli A Critical Companion to Zoosemiotics People, Paths, Ideas 123 Dario Martinelli University of Helsinki Institute of Art Research Faculty of Arts PL 35 (Vironkatu 1)