Supporting Longer Term Development in Crises at the Nexus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central African Republic Situation

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION UNHCR REGIONAL UPDATE 36 11-17 October 2014 KEY FIGURES HIGHLIGHT 410,000 IDPs including The UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative (SRSG) and head of the 60,093 United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the in Bangui Central African Republic (MINUSCA), Mr. Babacar Gaye, requested that all concerned parties ensure the implementation of the Brazzaville agreement as he believes that the recent crisis in Bangui is partly due to its non-application. 427,256 Mr. Gaye believes that enforcement of the agreement, signed on 23 July Total number of CAR refugees in 2014, would lead to the end of the crisis and provide a way to return to neighbouring countries constitutional order. 187,690 New CAR refugees in neighbouring The Senior Humanitarian Coordinator (SHC) in the Central African Republic countries since Dec. 2013 (CAR), Ms. Claire Bourgeouis made a statment on 13 October condemning the recruitment of children and the use of children in armed conflict, as has reportedly been the case in the recent violence in Bangui. The killing of two 8,012 children in the capital city accused of being spies and another child killed in the Refugees and asylum seekers in cross-fire were reported. Ms. Bourgeois also condemned children being used CAR to control barricades in parts of the city and called for community leaders and parents to prevent children being associated with demonstrations. FUNDING USD 255 million requested for the situation Population of concern (as at 17 October) Funded 33% A total of 837,256 people of concern Gap IDPs in CAR 410,000 67% Refugees in Cameroon 242,936 PRIORITIES Refugees in Chad 95,892 . -

EST Journal Des Proj

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX - TRAVAIL - PATRIE PEACE - WORK - FATHERLAND DETAILS DES PROJETS PAR REGION, DEPARTEMENT, CHAPITRE, PROGRAMME ET ACTION OPERATIONS BOOK PER REGION, DIVISION, HEAD, PROGRAMME AND ACTION Exercice/ Financial year : 2017 Région EST Region EAST Département LOM-ET-DJEREM Division En Milliers de FCFA In Thousand CFAF Année de Tâches démarrage Localité Montant AE Montant CP Tasks Starting Year Locality Montant AE Montant CP Chapitre/Head MINISTERE DE L'ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION 07 MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION AND DECENTRALIZATION Bertoua: Réhabiloitation des servcices du Gouverneur de la Région de l'Est Nkol-Bikon 55 000 55 000 2 017 Bertoua: Rehabiloitation of Governor's Office Ngoura: Règlement de la première phase des travaux de construction de la Sous- NGOURA 50 000 50 000 Préfecture 2 017 Ngoura: Payement of the first part of the construction of the Sub-Divisional Office Bertoua II: Règlement des travaux de construction de la résidence du Sous-Préfet BERTOUA 3 050 3 050 2 017 Bertoua II: Payment of the construction of the residence of the DO Total Chapitre/Head MINATD 108 050 108 050 Chapitre/Head MINISTERE DES MARCHES PUBLICS 10 MINISTRY OF PUBLIC CONTRACTS DR MINMAP EST: Travaux de réhabilitation de la délégation régionale Bertoua 25 000 25 000 2 017 RD MINPC East : Rehabilitatioon woks of the delegation Total Chapitre/Head MINMAP 25 000 25 000 Chapitre/Head MINISTERE DE LA DEFENSE 13 MINISTRY OF DEFENCE 11° BA: Construction salle opérationnelle modulable -

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION UNHCR REGIONAL UPDATE 38 25-31 October 2014 KEY FIGURES HIGHLIGHT 410,000 Idps Including

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION UNHCR REGIONAL UPDATE 38 25-31 October 2014 KEY FIGURES HIGHLIGHT 410,000 IDPs including 62,326 On 27 October, UNHCR’s Regional Refugee Coordinator (RRC) for the Central African Republic (CAR) Situation, Ms. Liz Ahua, participated in a in Bangui roundtable consultation on the regional refugee dimension of the CAR situation, in Brussels, hosted by UNHCR and the United States Mission to 420,237 the European Union (EU). The objectives of the event were to draw Total number of CAR refugees in increased attention to the regional aspects of the CAR refugee situation, neighbouring countries seek to raise it higher on the EU’s policy, political and funding agenda, and to highlight UNHCR’s role, achievements and challenges in providing protection and assistance. It was also an opportunity to encourage 183,443 humanitarian and development support to cover basic and long term needs New CAR refugees in neighbouring for refugees, highlight the importance of creative strategies to address countries since Dec. 2013 longer-term issues, such as promoting self-sufficiency and refugee participation in reconciliation efforts. In order to secure media attention to 8,012 the regional refugee situation, Ms. Ahua also gave interviews on the latest Refugees and asylum seekers in developments to BBC Africa, VOA News and Channel Africa. CAR FUNDING Population of concern USD 255 million A total of 830,237 people of concern requested for the situation Funded IDPs in CAR 410,000 33% Refugees in Cameroon 239,106 Gap 67% Refugees in Chad 92,606 PRIORITIES Refugees in DRC 68,156 . -

Joshua Osih President

Joshua Osih President THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVERSITY PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 2018 JOSHUA OSIH | THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVERSITY | P . 1 MY CONTRACT WITH THE NATION Build a new Cameroon through determination, duty to act and innovation! I decided to run in the presidential election of October 7th to give the youth, who constitute the vast majority of our population, the opportunity to escape the despair that has gripped them for more than three decades now, to finally assume responsibility for the future direction of our highly endowed nation. The time has come for our youth to rise in their numbers in unison and take control of their destiny and stop the I have decided to run in the presidential nation’s descent into the abyss. They election on October 7th. This decision, must and can put Cameroon back on taken after a great deal of thought, the tracks of progress. Thirty-six years arose from several challenges we of selfish rule by an irresponsible have all faced. These crystalized into and corrupt regime have brought an a single resolution: We must redeem otherwise prosperous Cameroonian Cameroon from the abyss of thirty-six nation to its knees. The very basic years of low performance, curb the elements of statecraft have all but negative instinct of conserving power disappeared and the citizenry is at all cost and save the collapsing caught in a maelstrom. As a nation, system from further degradation. I we can no longer afford adequate have therefore been moved to run medical treatment, nor can we provide for in the presidential election of quality education for our children. -

Cameroon : Adamawa, East and North Rgeions

CAMEROON : ADAMAWA, EAST AND NORTH RGEIONS 11° E 12° E 13° E 14° E N 1125° E 16° E Hossere Gaval Mayo Kewe Palpal Dew atan Hossere Mayo Kelvoun Hossere HDossere OuIro M aArday MARE Go mbe Trabahohoy Mayo Bokwa Melendem Vinjegel Kelvoun Pandoual Ourlang Mayo Palia Dam assay Birdif Hossere Hosere Hossere Madama CHARI-BAGUIRMI Mbirdif Zaga Taldam Mubi Hosere Ndoudjem Hossere Mordoy Madama Matalao Hosere Gordom BORNO Matalao Goboum Mou Mayo Mou Baday Korehel Hossere Tongom Ndujem Hossere Seleguere Paha Goboum Hossere Mokoy Diam Ibbi Moukoy Melem lem Doubouvoum Mayo Alouki Mayo Palia Loum as Marma MAYO KANI Mayo Nelma Mayo Zevene Njefi Nelma Dja-Lingo Birdi Harma Mayo Djifi Hosere Galao Hossere Birdi Beli Bili Mandama Galao Bokong Babarkin Deba Madama DabaGalaou Hossere Goudak Hosere Geling Dirtehe Biri Massabey Geling Hosere Hossere Banam Mokorvong Gueleng Goudak Far-North Makirve Dirtcha Hwoli Ts adaksok Gueling Boko Bourwoy Tawan Tawan N 1 Talak Matafal Kouodja Mouga Goudjougoudjou MasabayMassabay Boko Irguilang Bedeve Gimoulounga Bili Douroum Irngileng Mayo Kapta Hakirvia Mougoulounga Hosere Talak Komboum Sobre Bourhoy Mayo Malwey Matafat Hossere Hwoli Hossere Woli Barkao Gande Watchama Guimoulounga Vinde Yola Bourwoy Mokorvong Kapta Hosere Mouga Mouena Mayo Oulo Hossere Bangay Dirbass Dirbas Kousm adouma Malwei Boulou Gandarma Boutouza Mouna Goungourga Mayo Douroum Ouro Saday Djouvoure MAYO DANAY Dum o Bougouma Bangai Houloum Mayo Gottokoun Galbanki Houmbal Moda Goude Tarnbaga Madara Mayo Bozki Bokzi Bangei Holoum Pri TiraHosere Tira -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

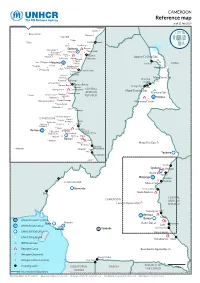

CAMEROON Reference Map As of 21 Feb 2019

CAMEROON Reference map as of 21 Feb 2019 Mbodo F Djakon F F Beke chantier NIGER Dompta F F Goundjel F Ndip F Beka Yamba DF Yamba F Belel Yarmbang F Borgop F Djohong F#B Nyambaka F F F F Ouro-Adde Babongo F Mbondo F F F DF Garga Libona F Gbata F F F F #B Ngaoui F Mboula F Logone-Et-Chari Dpt Mbarang Ngam F Alhamdou Bafouck H¹ F Ngazi D Simi F F Bigoro F F H¹ Meiganga A F Mikila Fotokol CHAD F Bagodo F Goro F Kombo Laka F F F F Gadi Foulbe Kousséri F Lokoti Dir Kounde DF Gbatoua Gbatoua Godole Mbale F Ngodole Bindiba F Mayo Sava Dpt F Amchide Komboul F Mbonga H¹ / Banki F Dang Patou DF D H¹ Garoua-Boulai Garoua Boulai D F Ashigashiya D Yokosire H¹H¹ Mborguene F B Gado Badzere CENTRAL # Mayo-Tsanaga Dpt H¹ F AFRICAN F Nandoungue Diamare Dpt F Betare Oya F Mombal Bouli Sodenou REPUBLIC F A Ndokayo FF #B Maroua Ndanga Gandima F Zembe Borongo Minawao/Gawar F Garga Sarali Woumbou F Ouli F F NIGERTIoAcktoyo F Guiwa Yangamo CAMEROON F F Samba Kette FRoma Boulembe Bedobo F F F F Moinam F Tapare Gbiti F DF Adinkol F F Mobe F F #B Timangolo Gbakim F Bertoua A F Bazzama Bougogo Sandji 1 F F FF F Kambele Bombe Pana Belebina F Nguindi F F Nyabi FF Mbile F F F Batouri #B Mboum #B Lolo F Pana Mayo-Rey Dpt H¹ Kentzou F D Kentzou F F Mbomba Ndelele F F Mbombete Yola DF Touboro Gari Gombo Gribi F Yamba D Djohong #B Borgop Ngam B D #Ngaoui D Meiganga A Gbatoua H¹ H¹ D Ngodole Akwaya Dpt Mbere Dpt Bamenda Garoua Boulai D D Ekok Gado Badzere #B CENTRAL CAMEROON AFRICAN H¹ Lom-Et-Djerem Dpt REPUBLIC Gbiti Timangolo D A Bertoua #B Batouri Mbile A UNHCR Country -

Signatory Cities and Municipalities

Cities #WithRefugees Signatory Cities and Municipalities Abbottabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Grande-Synthe, Hauts-de-France, France Paris, Île-de-France, France Adana, Mediterranean Region, Turkey Greater Dandenong, Victoria, Australia Paterson, NJ, USA Aix-les-Bains, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France Guarulhos, Sao Paulo, Brazil Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Alba, Provincia di Cuneo, Italy Hangu District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Albuquerque, NM, USA Pakistan Pessat-Villeneuve, Auvergne-Rhône- Albury City, New South Wales, Australia Hargeisa, Somaliland Alpes, France Altena, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Hobart, Tasmania, Australia Philadelphia, PA, USA Amsterdam, North Holland, Netherlands Houston, TX, USA Pittsburgh, PA, USA Anchorage, AK, USA Hull, East Riding of Yorkshire, UK Port Moody, BC, Canada Ann Arbor, MI, USA Jackson, WY, USA Prince Albert, SK, Canada Arica, Arica y Parinacota Region, Chile Jacksonville, FL, USA Providence, RI, USA Athens, Attica, Greece Jonava District Municipality, Lithuania Puerto Asís, Putumayo, Colombia Atlanta, GA, USA Kabul, Afghanistan Queanbeyan, New South Wales, Baku, Azerbaijan Kalumbila town Council, Zambia Australia Bannu, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Kampala, Central Region, Uganda Quibdó, Chocó Department, Colombia Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain Kentzou, East Region, Cameroon Quilicura, Santiago Metropolitan Region, Batouri, East Region, Cameroon Kette, East Region, Cameroon Chile Berbera, Sahil, Somaliland/Somalia Kigali, Rwanda Quito, Pichincha Province, Ecuador Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy -

Programmation De La Passation Et De L'exécution Des Marchés Publics

PROGRAMMATION DE LA PASSATION ET DE L’EXÉCUTION DES MARCHÉS PUBLICS EXERCICE 2021 JOURNAUX DE PROGRAMMATION DES MARCHÉS DES SERVICES DÉCONCENTRÉS ET DES COLLECTIVITÉS TERRITORIALES DÉCENTRALISÉES RÉGION DE L’EST EXERCICE 2021 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de Montant des N° Désignation des MO/MOD N° Page Marchés Marchés 1 Services déconcentrés régionaux 11 410 000 000 3 2 Communaute Urbaine de Bertoua 13 355 600 000 4 Département de la Boumba et Ngoko 3 Services déconcentrés 1 30 000 000 6 4 Commune de Gari Gombo 9 216 000 000 6 5 Commune de Moloundou 8 195 000 000 6 6 Commune de Salapoumbé 12 312 210 000 7 7 Commune de Yokadouma 11 290 500 000 8 TOTAL 41 1 043 710 000 Département du Haut-Nyong 8 Services Déconcentrés 7 340 466 000 9 9 Commune d'Angossas 9 208 000 000 9 10 Commune d'Atok 7 272 000 000 10 11 Commune d'Abong-Mbang 9 191 944 000 11 12 Commune de Dimako 7 272 000 000 11 13 Commune de Doumaintang 9 196 500 000 12 14 Commune de Lomié 13 298 000 000 12 15 Commune de Mboma 8 236 200 000 13 16 Commune de Messok 10 217 949 998 14 17 Commune de Mindourou 6 213 250 000 14 18 Commune de Ngoyla 17 377 065 000 15 19 Commune de Nguelemendouka 12 357 000 000 16 20 Commune de Samalomo 8 140 500 000 17 21 Commune de Doumé 20 285 500 000 17 22 Commune de Messamena 12 389 300 000 19 TOTAL 154 3 995 674 998 MINMAP/Division de la Programmation et du Suivi des Marchés Publics Page 1 sur 35 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de Montant des N° Désignation des MO/MOD N° Page Marchés -

Artisanal Mining, a Challenge to the Kimberley Process

ARTISANAL MINING, A CHALLENGE TO THE KIMBERLEY PROCESS: CASE STUDY OF THE KADEY DIVISION, EAST REGION OF CAMEROON This work is the product of the RELUFA Extractive Industries Program team. RELUFA would like to thank the German Technical Cooperation GIZ in Yaounde for the financial support that made the conduct of this study possible. Authors: Willy Cedric Foumena and Jaff Napoleon Bamenjo RELUFA January 2013 I II Acknowledgement The production of this study was led by Willy Cedric Foumena, RELUFA Extractive Industries Program Manager with the assistance of Jaff Napoleon Bamenjo, Coor - dinator of RELUFA. The decision to conduct the study was partially inspired by the recent admission of Cameroon as a participant in the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme that seeks to avoid trade in conflict diamonds. We would like to thank Alexander Kopp and the GIZ office in Yaounde for their fi - nancial support. The study team benefitted from extensive discussions with Mr Jean Kisito Mvogo and Essomba Jean Marcel both of the National Permanent Secretariat of the Kim - berley Process in Cameroon. Brendan Schwartz and Mireille Fouda Effa gave a hel - ping hand and provided valuable documentation and insights on artisanal mining and the Kimberley process. We would also like to recognize the efforts of Michel Bissou, Franck Hameni Bieleu, Osrich Yimbu, who all participated in gathering data on the field in the Kadey Di - vision of the east region of Cameroon. The contribution of our field partners from local civil society organization in the east region is acknowledged. They include Bernard Mbom, Salomon Tidike and Gaston Omboli. -

Cameroon's 4Th-6Th Periodic Reports

RÉPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix- Travail – Patrie Peace – Work – Fatherland ----------- ----------- Single Report comprising the 4th, 5th and 6thPeriodic Reports of Cameroon relating to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and 1st Reports relating to the Maputo Protocol and the Kampala Convention Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................. x GENERAL INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 PART A: .................................................................................................................................................. 3 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE RIGHTS ............................................................................................... 3 CONTAINED IN THE CHARTER ........................................................................................................ 3 CHAPTER 1: STRATEGIC, NORMATIVE AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK IN THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS ............................................................ 4 Section 1: Adoption of the National Plan of Action for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights (2015-2019).............................................................................................................................. 4 Section 2: Normative Framework ...................................................................................................... -

Association Des Communes Forestières Du Cameroun (ACFCAM)

Association des Communes Forestières du Cameroun (ACFCAM) CENTRE TECHNIQUE DE LA FORET COMMUNALE (CTFC) Rapport D’activités Deuxième Semestre 2009 Préambule Le Centre Technique de la Forêt Communale (CTFC) enregistrée le 30 juillet 2009 sous le N°001000/RDA/JO6/BAPP portant liberté d’association au Cameroun est l’agence d’exécution de l’Association des communes forestières du Cameroun (ACFCam) pour la mise en œuvre du Programme d’Appui aux Forêts communales du Cameroun (PAF2C). Le « Programme d’appui aux Forêts communales du Cameroun (PAF2C) » est le produit de la volonté conjointe de l’ACFCam (Association des Communes forestières du Cameroun) et du groupement FNCoFor/ONF (Fédération nationale des Communes forestières de France et son partenaire technique, l’Office national des Forêts) de renforcer le réseau des forêts communales en accompagnant le processus de décentralisation de la gestion des ressources naturelles. Les bénéficiaires du Programme d´Appui aux Forêts Communales du Cameroun (PAF2C) sont les Communes membres de l´ACFCAM et leurs cellules de foresterie communale. Le CTFC a pour missions en interne ou en partenariat : l’Aménagement forestier, les Inventaires multi ressources (flore, faune, PFNL, etc.), les diagnostics écologiques, les enquêtes socioéconomiques, les évaluations / études d’impact environnemental, Cartographie, télédétection & SIG, l’élaboration de modules de formation, les contrats d’approvisionnement, la valorisation de déchets de l’exploitation et du sciage ( carbonisation, cogénération), l’augmentation des