Firewise.Org Oakland/Berkeley Hills Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Existing Conditions

2. EXISTING CONDITIONS This chapter provides a description of existing conditions within the City of Lafayette relevant to the Bikeways Master Plan. Information is based on site visits, existing planning documents, maps, and conversations with Lafayette residents and City of Lafayette, Contra Costa County and other agency staff. 2.1. SETTING The City of Lafayette is situated in a semi-rural valley in Contra Costa County, approximately twenty miles east of San Francisco, on the east side of the Oakland/Berkeley hills. Lafayette has a population of approximately 24,000, and encompasses about 15 square miles of land area, for a population density of about 1,500 persons per square mile. Settlement started in the late 1800s but incorporation did not occur until 1968. Lafayette developed its first general plan in 1974, and this general plan was last updated in 2002. The City is bordered on the north by Briones Regional Lafayette-Moraga Trail along St. Mary’s Park, on the east by Walnut Creek, on the south by Moraga and Road near Florence Drive the west by Orinda. Mixed in along its borders are small pockets of unincorporated Contra Costa County. Lafayette has varied terrain, with steep hills located to the north and south. Highway 24 runs through the City, San Francisco is a 25-minute BART ride away, and Oakland’s Rockridge district is just two BART stops away. LAFAYETTE LAND USES Lafayette’s existing development consists mostly of low- to medium-density single family residential, commercial, parkland and open space. Land uses reflect a somewhat older growth pattern: Commercial areas are located on both sides of Mt. -

TR-060, the East Bay Hills Fire Oakland-Berkeley, California, October 1991* United States Fire Administration Technical Report Series

TR-060, The East Bay Hills Fire Oakland-Berkeley, California, October 1991* United States Fire Administration Technical Report Series The East Bay Hills Fire Oakland-Berkeley, California Federal Emergency Management Agency United States Fire Administration National Fire Data Center United States Fire Administration Fire Investigations Program The United States Fire Administration develops reports on selected major fires throughout the country. The fires usually involve multiple deaths or a large loss of property. But the primary criterion for deciding to do a report is whether it will result in significant "lessons learned." In some cases these lessons bring to light new knowledge about fire -the effect of building construction or contents, human behavior in fire, etc In other cases, the lessons are not new but are serious enough to highhght once again, with yet another fire tragedy report. The reports are Sent to fire magazines and are distributed at national and regional fire meetings. The International Association of Fire Chiefs assists USFA in disseminating the findings throughout the fire service.. On a continuing basis the reports are available on request from USFA; announcements of their availability are published widely in fire journals and newsletters This body of work provides detailed information on the nature of the fire problem for policymakers who must decide on allocations of resources between fire and other pressing problems, and within the fire service to improve codes and code enforcement, training, public tire education, building technology, and other related areas The Fire Administration, which has no regulatory authority, sends an cxperienced fire investigator into a community after a major incident only after having conferred with the local tire authorities to insure that USFA's assistance and presence would be supportive and would in no way interfere with any review of the incident they are themselves conducting. -

Contra Costa County

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration CONTRA COSTA COUNTY Marsh Creek Watershed Marsh Creek flows approximately 30 miles from the eastern slopes of Mt. Diablo to Suisun Bay in the northern San Francisco Estuary. Its watershed consists of about 100 square miles. The headwaters of Marsh Creek consist of numerous small, intermittent and perennial tributaries within the Black Hills. The creek drains to the northwest before abruptly turning east near Marsh Creek Springs. From Marsh Creek Springs, Marsh Creek flows in an easterly direction entering Marsh Creek Reservoir, constructed in the 1960s. The creek is largely channelized in the lower watershed, and includes a drop structure near the city of Brentwood that appears to be a complete passage barrier. Marsh Creek enters the Big Break area of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta northeast of the city of Oakley. Marsh Creek No salmonids were observed by DFG during an April 1942 visual survey of Marsh Creek at two locations: 0.25 miles upstream from the mouth in a tidal reach, and in close proximity to a bridge four miles east of Byron (Curtis 1942). -

Wildcat Creek Restoration Action Plan Version 1.3 April 26, 2010 Prepared by the URBAN CREEKS COUNCIL for the WILDCAT-SAN PABLO WATERSHED COUNCIL

wildcat creek restoration action plan version 1.3 April 26, 2010 prepared by THE URBAN CREEKS COUNCIL for the WILDCAT-SAN PABLO WATERSHED COUNCIL Adopted by the City of San Pablo on August 3, 2010 wildcat creek restoration action plan table of contents 1. INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 plan obJectives 5 1.2 scope 6 Urban Urban 1.5 Methods 8 1.5 Metadata c 10 reeks 2. WATERSHED OVERVIEW 12 c 2.1 introdUction o 12 U 2.2 watershed land Use ncil 13 2.3 iMpacts of Urbanized watersheds 17 april 2.4 hydrology 19 2.5 sediMent transport 22 2010 2.6 water qUality 24 2.7 habitat 26 2.8 flood ManageMent on lower wildcat creek 29 2.9 coMMUnity 32 3. PROJECT AREA ANALYSIS 37 3.1 overview 37 3.2 flooding 37 3.4 in-streaM conditions 51 3.5 sUMMer fish habitat 53 3.6 bioassessMent 57 4. RECOMMENDED ACTIONS 58 4.1 obJectives, findings and strategies 58 4.2 recoMMended actions according to strategy 61 4.3 streaM restoration recoMMendations by reach 69 4.4 recoMMended actions for phase one reaches 73 t 4.5 phase one flood daMage redUction reach 73 able of 4.6 recoMMended actions for watershed coUncil 74 c ontents version 1.3 april 26, 2010 2 wildcat creek restoration action plan Urban creeks coUncil april 2010 table of contents 3 figUre 1-1: wildcat watershed overview to Point Pinole Regional Shoreline wildcat watershed existing trail wildcat creek highway railroad city of san pablo planned trail other creek arterial road bart Parkway SAN PABLO Richmond BAY Avenue San Pablo Point UP RR San Pablo WEST COUNTY BNSF RR CITY OF LANDFILL NORTH SAN PABLO RICHMOND San Pablo -

Classy City: Residential Realms of the Bay Region

Classy City: Residential Realms of the Bay Region Richard Walker Department of Geography University of California Berkeley 94720 USA On-line version Revised 2002 Previous published version: Landscape and city life: four ecologies of residence in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ecumene . 2(1), 1995, pp. 33-64. (Includes photos & maps) ANYONE MAY DOWNLOAD AND USE THIS PAPER WITH THE USUAL COURTESY OF CITATION. COPYRIGHT 2004. The residential areas occupy the largest swath of the built-up portion of cities, and therefore catch the eye of the beholder above all else. Houses, houses, everywhere. Big houses, little houses, apartment houses; sterile new tract houses, picturesque Victorian houses, snug little stucco homes; gargantuan manor houses, houses tucked into leafy hillsides, and clusters of town houses. Such residential zones establish the basic tone of urban life in the metropolis. By looking at residential landscapes around the city, one can begin to capture the character of the place and its people. We can mark out five residential landscapes in the Bay Area. The oldest is the 19th century Victorian townhouse realm. The most extensive is the vast domain of single-family homes in the suburbia of the 20th century. The grandest is the carefully hidden ostentation of the rich in their estates and manor houses. The most telling for the cultural tone of the region is a middle class suburbia of a peculiar sort: the ecotopian middle landscape. The most vital, yet neglected, realms are the hotel and apartment districts, where life spills out on the streets. More than just an assemblage of buildings and styles, the character of these urban realms reflects the occupants and their class origins, the economics and organization of home- building, and larger social purposes and planning. -

Beautiful Berkeley Hills a Walk Through History * Alameda County

BEAUTIFUL BERKELEY HILLS A WALK THROUGH HISTORY * ALAMEDA COUNTY Overview This fairly strenuous, 6-mile hike follows Strawberry Creek from downtown Berkeley through the University of California campus into Strawberry Canyon, then over the ridge into Claremont Canyon and back down to the Berkeley flatlands. This hike highlights the land use decisions that have created the greenbelt of open space within easy reach of Berkeley’s vibrant communities. Location: Berkeley, CA Hike Length & Time: 6 miles, Allow 3-5 hours depending on your uphill speed Elevation Gain: 1000 ft Rating: Challenging Park Hours: No restrictions Other Information: Dogs on leash, no bikes on fire trails, kid friendly Getting There Driving: From Hwy 80/580 take the University Ave. exit and drive east toward the hills for about 2 miles to Shattuck Avenue. Turn right onto Shattuck and in 2 blocks you’ll hit Center Street where the hike begins. Street parking can be hard to find, and is limited to 2 hours (except Sunday). You can pay to park in garages on Addison and Center streets (go right off Shattuck), or in a parking lot on Kittredge Street (go left off Shattuck). Public Transit: This hike is easily accessible via AC Transit lines 40, 51, 64 and others, or via BART to the downtown Berkeley BART station. See www.bart.gov for train schedules or www.transitinfo.org for information on Alameda County Transit. Trailhead: The trailhead for this hike is the rotunda above the main entrance to the downtown Berkeley BART station at the corner of Shattuck Avenue and Center Street. -

The East Bay Hills Fire, Oakland-Berkeley, California

U.S. Fire Administration/Technical Report Series The East Bay Hills Fire Oakland-Berkeley, California USFA-TR-060/October 1991 U.S. Fire Administration Fire Investigations Program he U.S. Fire Administration develops reports on selected major fires throughout the country. The fires usually involve multiple deaths or a large loss of property. But the primary criterion T for deciding to do a report is whether it will result in significant “lessons learned.” In some cases these lessons bring to light new knowledge about fire--the effect of building construction or contents, human behavior in fire, etc. In other cases, the lessons are not new but are serious enough to highlight once again, with yet another fire tragedy report. In some cases, special reports are devel- oped to discuss events, drills, or new technologies which are of interest to the fire service. The reports are sent to fire magazines and are distributed at National and Regional fire meetings. The International Association of Fire Chiefs assists the USFA in disseminating the findings throughout the fire service. On a continuing basis the reports are available on request from the USFA; announce- ments of their availability are published widely in fire journals and newsletters. This body of work provides detailed information on the nature of the fire problem for policymakers who must decide on allocations of resources between fire and other pressing problems, and within the fire service to improve codes and code enforcement, training, public fire education, building technology, and other related areas. The Fire Administration, which has no regulatory authority, sends an experienced fire investigator into a community after a major incident only after having conferred with the local fire authorities to insure that the assistance and presence of the USFA would be supportive and would in no way interfere with any review of the incident they are themselves conducting. -

Land Use and Water Quality at Wildcat Creek, CA Tim Hassler Abstract

Land Use and Water Quality at Wildcat Creek, CA Tim Hassler Abstract Urban creeks and their associated watersheds are the focal point for a variety of different land uses including, urban development, industry, agriculture, livestock grazing, and recreational activities. These land uses can threaten the water quality of urban creeks. Most land-use studies have focused on multiple watersheds over a regional scale. More localized information is needed on single streams to provide important water quality information so they can be better managed. This study looked at the relationship between various land uses and water quality along Wildcat Creek, Berkeley, CA to determine if urban development, recreational activities, and livestock grazing may negatively affect the health of the creek. The study area was divided into seven discrete usage zones based on varying land uses. Water samples were collected three times over a four-month period to look for temporal variation in pH, conductivity, turbidity, and nitrates. Samples were also collected and analyzed for E-Coli bacteria once during the study. Regulatory guidelines and/or standards were used to assess the water quality of the creek. pH levels were found to be consistent throughout each usage zone. Conductivity levels increased downstream with the exception of the Lake Anza usage zone (a swimming reservoir), where they dropped sharply, possibly due to a settling effect. Turbidity levels fluctuated between usage zones showing no set pattern. Nitrate loading generally increased downstream throughout the study area. Conductivity levels were significantly correlated over time among the different usage zones, while the other sample parameters did not show significant temporal correlation. -

Visit-Berkeley-Official-Visitors-Guide

Contents 3 Welcome 4 Be a Little Berkeley 6 Accommodations 16 Restaurants 30 Local Libations 40 Arts & Culture 46 Things to Do 52 Shopping Districts 64 #VisitBerkeley 66 Outdoor Adventures & Sports 68 Berkeley Marina 70 Architecture 72 Meetings & Celebrations 76 UC Berkeley 78 Travel Information 80 Transportation 81 Visitor & Community Services 82 Maps visitberkeley.com BERKELEY WELCOMES YOU! The 2018/19 Official Berkeley Visitors Guide is published by: Hello, Visit Berkeley, 2030 Addison St., Suite #102, Berkeley, CA 94704 (510) 549-7040 • www.visitberkeley.com Berkeley is an iconic American city, richly diverse with a vibrant economy inspired in EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE great measure by our progressive environ- Greg Mauldin, Chairman of the Board;General Manager, Hotel Shattuck Plaza Vice Chair, (TBA); mental and social policies. We are internationally recognized for our arts Thomas Burcham, Esq., Secretary/Treasurer; Worldwide Farmers and culinary scenes, as well as serving as home to the top public univer- Barbara Hillman, President & CEO, Visit Berkeley sity in the country – the University of California, Berkeley. UC Berkeley BOARD OF DIRECTORS is the heart of our city, and our neighborhood districts surround the Cal John Pimentel, Account Exec/Special Projects, Hornblower Cruises & Events campus with acclaimed restaurants, great independent shops and galleries, Lisa Bullwinkel, Owner; Another Bullwinkel Show world-class performing arts venues, and wonderful parks. Tracy Dean, Owner; Design Site Hal Leonard, General Manager; DoubleTree by Hilton Berkeley Marina I encourage you to discover Berkeley’s signature elements, events and Matthew Mooney, General Manager, La Quinta Inn & Suites LaDawn Duvall, Executive Director, Visitor & Parent Services UC Berkeley engaging vibe during your stay with us. -

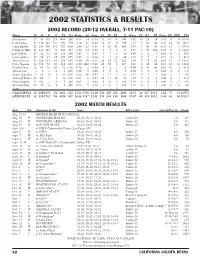

2002 Statistics & Results

2002 STATISTICS & RESULTS 2002 RECORD (20-12 OVERALL, 7-11 PAC-10) Player M G K E TA Pct K/avg Ast A/avg SA SE RE D D/avg BS BA TB B/avg BE BHE PTS Mia Jerkov 27 98 578 233 1400 .246 5.90 14 0.14 33 51 13 345 3.52 10 28 38 0.39 4 4 635.0 Leah Young 32 120 384 111 994 .275 3.20 82 0.68 18 19 5 255 2.12 3 83 86 0.72 10 19 446.5 Jenna Brown 32 119 340 174 924 .180 2.86 23 0.19 8 28 33 365 3.07 7 46 53 0.45 13 3 378.0 Camille Leffall 31 113 253 71 525 .347 2.24 11 0.10 1 1 0 31 0.27 9 99 108 0.96 9 1 312.5 Lisa Collette 13 22 32 20 120 .100 1.45 1 0.05 2 7 5 10 0.45 1 2 3 0.14 0 0 36.0 Jessica Zatica 19 34 37 25 159 .075 1.09 6 0.18 1 1 6 40 1.18 0 7 7 0.21 0 1 41.5 Alicia Powers 32 120 113 63 336 .149 0.94 30 0.25 28 39 22 323 2.69 7 75 82 0.68 13 5 185.5 Caity Noonan 32 118 94 26 260 .262 0.80 1442 12.22 42 58 0 287 2.43 3 42 45 0.38 12 16 160.0 Heather Diers 25 49 38 20 92 .196 0.78 2 0.04 0 2 2 2 0.04 6 34 40 0.82 10 1 61.0 Allison Ara 2 2 1 0 2 .500 0.50 0 0.00 0 0 0 0 0.00 0 0 0 0.00 0 0 1.0 Astrid Gonzalez 9 18 4 2 21 .095 0.22 88 4.89 1 1 1 21 1.17 0 1 1 0.06 2 3 5.5 Ashleigh Turner 22 88 1 3 20 -.100 0.01 6 0.07 10 13 18 94 1.07 0 0 0 0.00 0 1 11.0 Jenna Grigsby 31 102 1 0 5 .200 0.01 2 0.02 5 10 5 100 0.98 0 0 0 0.00 0 1 6.0 Alexis Kollias 29 92 0 0 5 .000 0.00 9 0.10 0 0 7 108 1.17 0 0 0 0.00 0 0 0.0 Team 9 CALIFORNIA 32 120 1876 748 4863 .232 15.63 1716 14.30 149 230 126 1981 16.51 46 417 254.5 2.12 73 55 2279.5 OPPONENTS 32 120 1761 764 4820 .207 14.68 1597 13.31 126 284 149 1808 15.07 69 453 295.5 2.46 68 68 2182.5 2002 MATCH RESULTS Date W/L Opponent & Site Score Kill Leader Overall/Pac-10 Attend. -

Shattuck Avenue Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey

Shattuck Avenue Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey Prepared for: City of Berkeley Department of Planning and Development City of Berkeley 2120 Milvia St. Berkeley, CA 94704 Attn: Sally Zarnowitz, Principal Planner Secretary to the Landmarks Preservation Commission 05.28.2015 FINAL DRAFT (Revised 08.26.2015) ARCHIVES & ARCHITECTURE, LLC PO Box 1332 San José, CA 95109-1332 http://www.archivesandarchitecture.com Shattuck Avenue Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey ACKNOWLEDGMENT The activity which is the subject of this historic context has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, through the California Office of Historic Preservation. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation. Regulations of the U.S. Department of the Interior strictly prohibit unlawful discrimination in departmental federally‐assisted programs on the basis of race, color, sex, age, disability, or national origin. Any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of Federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service P.O. Box 37127 Washington, DC 20013‐7127 Cover image: USGS Aerial excerpt, Microsoft Corporation ARCHIVES & ARCHITECTURE 2 Shattuck Avenue Commercial Corridor Historic Context and Survey Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... -

OAKLAND to Visit This Site, Walk up the Paved Road to the Road Walk up the Paved Visit This Site, to to Walnut Creek Walnut To

1600 BAY AREA RIDGE TRAIL 24 IN ORDER TO REDUCE OR LEGEND PREVENT THE RISK OF SERIOUS EBMUD WATERSHED. To Walnut Creek HEAD INJURY OR DEATH, STATE Hikers, Horses & Bicycles SKYL 1500 Hiking permit required 1400 LAW REQUIRES THAT ALL INE Hikers & Horses TRAIL except when hiking on BICYCLISTS UNDER AGE 18 WEAR G 1400 AN APPROVED HELMET WHILE Skyline Trail/Bay Area Ridge RI Water Skyline Trail/Bay Area 11 ZZ Tank 10 1500 RIDING ON TRAILS AND ROAD- LY Ridge Trail. Call Quarry Pit 5 Trail–Hikers & Horses PE .11 AK 13 WAYS. THE DISTRICT ALSO BL 00 (510) 287-0459. 9 .11 4 . 8 .04 Quarry Pit STRONGLY RECOMMENDS THAT Hikers Only 7 6 .28 .07 .19 ICT .14 ALL EQUESTRIANS AND 1300 .06 N R TRAI 3 2 .28 AREMONT AV A A VOL .03 .11 .04 Mileage Between Points CL . LC IL CANIC L .13 BICYCLISTS WEAR HELMETS AT O V 1400 ALL TIMES. Paved Road .04 .12 AIL LOOP .13 .08 TR .29 1.46 mi. from SIBLEY .15 Y Fish Ranch Road .15 QUARR 1300 DOGS AND HORSES ARE NOT Parking UNIVERSITY to Lomas Cantadas VOLCANIC 1600 TRAIL North PON .08 SIBLEY .17 D T 1500 and Tilden1200 Reg. Park R. TOP PERMITTED IN HUCKLEBERRY 13 Restrooms OF REGIONAL . OLD TUNNEL ROAD .29 VOLCANIC except passing through on the CALIFORNIA PRESERVE Q .41 Skyline National Trail/Bay Area Visitor Center U REGIONAL te 17 . 00 36 BERKELEY A ROUND va Ridge Trail. R 200 PRESERVE Pri Drinking Water RANCH ROAD 1200 R 1 PropertyEBMUD FISH Y BICYCLES ARE NOT PERMITTED R Self-guided tour 1.08 D Round Top IN HUCKLEBERRY PRESERVE.