Plot Parody in Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E-ISSN: 2536-4596

e-ISSN: 2536-4596 KARE- Uluslararası Edebiyat, Tarih ve Düşünce Dergisi KARE- International Journal of Literature, History and Philosophy Başlık/ Title: Parody and Mystery in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound and Jumpers Yazar/ Author ORCID ID Kenan KOÇAK 0000-0002-6422-2329 Makale Türü / Type of Article: Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Yayın Geliş Tarihi / Submission Date: 4 Ekim 2019 Yayına Kabul Tarihi / Acceptance Date: 18 Kasım 2019 Yayın Tarihi / Date Published: 25 Kasım 2019 Web Sitesi: https://karedergi.erciyes.edu.tr/ Makale göndermek için / Submit an Article: http://dergipark.gov.tr/kare Parody and Mystery in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound and Jumpers Yazar: Kenan KOÇAK ∗ Tom Stoppard’ın Gerçek Müfettiş Hound (The Real Inspector Hound) ve Akrobatlar (Jumpers) Oyunlarında Parodi ve Gizem1 Özet: Tom Stoppard, Çekoslavakya doğumlu ve İngilizce’yi sonradan öğrenmiş olması sebebiyle, anadili İngilizce olan yazarlara nazaran dile daha hâkim ve dilin imkanlarını daha iyi kullanabilen, kelimelerle oynamada mahir; komik diyaloglar, yanlış anlaşılmaya mahal vermeler ve beklenmedik cevaplar yaratabilen usta bir oyun yazarıdır. Kendisi öyle olduğunu reddetse de oyunlarında kimliğin ve hafızanın önemi, gerçek ve görünen arasındaki ilişki, hayatın sıkıntıları, kendinden ve kendinden önceki yazarlardan esinlenme ve ödünç alma gibi postmodern ve absürd tiyatronun tipik özelliklerini görmek mümkündür. İlk defa 1968 yılında sergilenen Gerçek Müfettiş Hound (The Real Inspector Hound) oyunu Agatha Christie’nin 1952 yapımı Fare Kapanı (The Mousetrap) oyununun bir parodisiyken Akrobatlar (Jumpers) akademik felsefenin satirik bir eleştirisidir. Stoppard, bu makalede incelenen Gerçek Müfettiş Hound ve Akrobatlar adlı oyunlarında kurgusunu oyunlarının başında yarattığı bir gizem üzerine inşa eder. Bu gizem Gerçek Müfettiş Hound’da sahneye diğer aktörlerce fark edilmeyen bir ceset koyarak gerçekleştirilirken Akrobatlar’ın en başında akrobatlardan birinin öldürülmesi ve kimin öldürdüğünün de oyun boyunca söylenmemesiyle sağlanır. -

Hyperreality in Tom Stoppard's the Real Inspector Hound Nasrin Nezamdoost Department of English Language, Karaj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Karaj, Iran

Hyperreality in Tom Stoppard's The Real Inspector Hound Nasrin Nezamdoost Department of English Language, Karaj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Karaj, Iran. [email protected] and Fazel Asadi Amjad Department of Foreign Languages, Tarbiat Moallem University, Tehran, Iran. Reality has been one of man's major concerns in different ages. Finding the actual reality becomes more intense in postmodern era due to the fact that most of realities are only considered as ''social constructs'' and they are subject to change (Tiedemann 62). Besides, as Hicks states, there is no ''absolute truth'' in this era (18). In other words, postmodernism lacks the ability to provide exact and meaningful statements about an "independently existing reality'' and replaces only a ''social-linguistic, constructionist account of reality'' (Hicks 6). Therefore, as Hoover holds, it renders ''plurality'' and multiplicity instead of individualism (xxvii). Post-structuralism which ''parallels'' with postmodernism (Abrams 169), presents this plurality, Sarup mentions, by referring to the ''floating signifier system'' (3), in which the signifiers and the signifieds are not "fixed" entities, and each "signifier" may refer to several signifieds (Roman 309). Postmodern era is bombarded with representation or re-imaging and distortions of reality, simulation and hyperreality which cast doubt, raise uncertainty about the real's validity, and make reality be masked and hidden. Tom Stoppard is an outstanding British playwright whose mind is occupied by investigating reality (Mackean 1) as the word 'real' in titles and themes of his plays suggest, but he tries to hide the truth in his plays and persuade his audiences that it is not a theater and; thus, fills their minds with ''convincing illusions'' (Jenkins x). -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases and gifts, 1991-2000 Processed by Katherine Mosley, 1993-2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Biographical Sketch Playwright Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler in Zlin, Czechoslovakia, on July 3, 1937. However, he lived in Czechoslovakia only until 1939, when his family moved to Singapore. Stoppard, his mother, and his older brother were evacuated to India shortly before the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1941; his father, Eugene Straussler, remained behind and was killed. In 1946, Stoppard's mother, Martha, married British army officer Kenneth Stoppard and the family moved to England, eventually settling in Bristol. Stoppard left school at the age of seventeen and began working as a journalist, first with the Western Daily Press (1954-58) and then with the Bristol Evening World (1958-60). -

Guide to the Dr. Gerald N. Wachs Collection of Tom Stoppard 1967-2013

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Dr. Gerald N. Wachs Collection of Tom Stoppard 1967-2013 © 2017 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Biographical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 5 Subject Headings 5 INVENTORY 5 Series I: Correspondence 5 Series II: Tom Stoppard: A Bibliographical History 6 Series III: Plays, Films, and Radio Productions 8 Series IV: Other Writings 13 Series V: Photographs 14 Series VI: Oversize 14 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.WACHS Title Wachs, Dr. Gerald N. Collection of Tom Stoppard Date 1967-2013 Size 7 linear feet (11 boxes, 1 oversize folder) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract The Dr. Gerald N. Wachs Collection contains materials relating to the production of Tom Stoppard’s plays on stage and screen – including advertising, playbills, reviews, and ephemera – and cards, letters, and photographs signed by Stoppard. Of particular note are drafts and working copies of scripts and screenplays, and first run programs. Also included are materials which were used in the preparation of Gerald Wachs’ Tom Stoppard bibliography, published by Oak Knoll Press in 2010 as Tom Stoppard: A Bibliographical History. Information on Use Access The collection is open for research. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: Wachs, Dr. Gerald N. Collection of Tom Stoppard, [Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. Biographical Note Gerald N. Wachs, M.D. (1937-2013) was a doctor and dermatologist from Millburn, New Jersey. -

Tom Stoppard Writer

Tom Stoppard Writer Please send all permissions and press requests to [email protected] Agents St John Donald Associate Agent Jonny Jones [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0928 Anthony Jones Associate Agent Danielle Walker [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0858 Rose Cobbe Assistant Florence Hyde [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0957 Credits Film Production Company Notes United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] ANNA KARENINA Working Title/Universal/Focus Screenplay from the novel by 2012 Features Tolstoy Directed by Joe Wright Produced by Tim Bevan, Paul Webster with Keira Knightley, Jude Law, Aaron Taylor-Johnson *Nominated for Outstanding British Film, BAFTA 2013 ENIGMA Intermedia/Paramount Screenplay from the novel by 2001 Robert Harris Directed by Michael Apted Produced by Mick Jagger, Lorne Michaels with Kate Winslet, Dougray Scott, Saffron Burrows VATEL Legende/Miramax English adaptation 2000 Directed by Roland Joffe Produced by Alain Goldman with Uma Thurman, Gerard Depardieu, Tom Roth United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE Miramax Screenplay from Marc Norman 1998 Directed by John Madden Produced by Donna Gigliotti, David Parfitt, Harvey Weinstein, Edward Zwick with Gwyneth Paltrow and Joseph Fiennes * Winner of a South Bank Show Award for Cinema 2000 * Winner of Best Screenplay, Evening Standard -

Modern & Post-War British Art (22 Apr 2021 C

Modern & Post-War British Art (22 Apr 2021 C) Thu, 22nd Apr 2021 Viewing: Viewing by appointment only. Sat 17 April, 11am - 5pm Sun 18 April, 11am - 5pm Mon 19 April, 10am - 5pm Tue 20 April, 10am - 5pm Wed 21 April, 10am - 5pm Thu 22 April, 10am - 1pm Please contact the Modern British & Post-War Art Department to book an appointment. Lot 344 Estimate: £800 - £1200 + Fees ALAN THORNHILL (1921-2020) PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ALAN THORNHILL (LOTS 338-353) ALAN THORNHILL (1921-2020) Tom Stoppard numbered 220 in silver pen (underneath) patinated terracotta 35 cm (13 3/4 in) high Tom Stoppard sat for this bust at his home in Iver, Buckinghamshire in 1973, a year after his play Jumpers had won the Evening Standard Award for Best Play and London Theatre Critics Award for Best New Play. Thornhill was inspired by the immediacy of live theatre and was a great fan of Stoppard's work. He recalled of the present bust: 'Dissatisfied with the first day's attempt I did another in one day and felt I had made a breakthrough'. Stoppard was born in Czechoslovakia in 1937. When the Nazis invaded the country in 1939, his parents fled with their two sons to Singapore where his father was killed. His mother then took the chidren to India where she remarried, to a British army Major Kenneth Stoppard. After the War the family settled in the north of England, when Stoppard took his step- father's name. After leaving Pocklington school at 17 he worked first as a journalist, and then as a theatre critic in Bristol whilst also developing his script writing. -

Decompositional Linguistic Models and Deconstructionism in Stoppard’S the Real Inspector Hound and Arcadia Erin Gough University of Lynchburg

University of Lynchburg Digital Showcase @ University of Lynchburg Undergraduate Theses and Capstone Projects Spring 4-2015 Stopping at Stoppard: Decompositional Linguistic Models and Deconstructionism in Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound and Arcadia Erin Gough University of Lynchburg Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalshowcase.lynchburg.edu/utcp Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gough, Erin, "Stopping at Stoppard: Decompositional Linguistic Models and Deconstructionism in Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound and Arcadia" (2015). Undergraduate Theses and Capstone Projects. 144. https://digitalshowcase.lynchburg.edu/utcp/144 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Showcase @ University of Lynchburg. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses and Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Showcase @ University of Lynchburg. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stopping at Stoppard: Decompositional Linguistic Models and Deconstructionism in Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound and Arcadia Erin Gough Senior Honors Project Submitted in partial fulfillment of the graduate requirements for Honors in the English Major April 2015 Dr. Robin Bates, Committee Chair Dr. Leslie Layne Dr. Chidsey Dickson Gough 1 This thesis will develop connections between the decomposition of binaries in the cognitive linguistic model of prototype theory and the deconstructionism of binaries in the literary critical theory of deconstructionism, focusing on Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound to show the operation of the theory in literature and using on Stoppard’s Arcadia as an example of an application of prototype theory as a critical lens. Prototype theory is a linguistically and psychologically-based theory of categorization which rejects the definition of categorization found in classical theory. -

FINAL FINAL Draft

Copyright by James Roslyn Jesson 2010 The Dissertation Committee for James Roslyn Jesson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Radio Texts: The Broadcast Drama of Orson Welles, Dylan Thomas, Samuel Beckett, and Tom Stoppard Committee: ___________________________________ Alan Friedman, Supervisor ___________________________________ Elizabeth Cullingford ___________________________________ Michael Kackman ___________________________________ James Loehlin ___________________________________ Elizabeth Richmond-Garza Radio Texts: The Broadcast Drama of Orson Welles, Dylan Thomas, Samuel Beckett, and Tom Stoppard by James Roslyn Jesson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe many people thanks for their encouragement and support during this project. I could not ask for a more generous and helpful committee. Alan Friedman introduced me to the drama of Samuel Beckett and shaped my understanding of Beckett’s approaches to writing and performance. Early in my graduate career he assured me that I could say something original about Beckett’s radio plays, and his praise for my work encouraged me to expand my focus to other authors’ radio drama. Over six years, Alan has been unfailingly supportive and generous with his time and advice on all matters academic and professional. Like Alan, James Loehlin has been a careful reader who has taught me much about my writing. I was inspired by his teaching in two seminars, and his guidance as the director of my Masters Report shaped my scholarship significantly. -

The Real Thing by Tom Stoppard

The Real Thing by Tom Stoppard Teachers’ Resource Pack Researched and written by Mitchell Moreno 2 THE REAL THING contents The Real Thing at The Old Vic 3 Chronology: Tom Stoppard, his Life and Works 4 Synopsis 5 Characters 7 Major themes and interests 10 In conversation with Director Anna Mackmin 12 Tom Stoppard: Portrait of a Playwright 15 Glossary of terms and references 16 3 THE REAL THING at the old vic Director Anna Mackmin Sound Simon Baker for Designer Lez Brotherston Autograph Lighting Hugh Vanstone Casting Toby Whale Tom Austen Louise Calf Barnaby Kay Hattie Morahan Billy Debbie Max Annie Toby Stephens Fenella Woolgar Jordan Young Henry Charlotte Brodie Jamie Partridge Cassie Raine Gemma Soul Simon Yadoo Understudy: Brodie/Billy Understudy: Charlotte/Annie Understudy: Debbie Understudy: Henry/Max 4 Chronology Tom Stoppard, his Life & Works 1937 – Born Tomáš Straussler in Zlin, 1967 – Teeth performed on TV. 1984 – The Real Thing staged on Czechoslovakia. – Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Broadway, winning five Tony 1939 – On the day the Nazis invade Dead staged at the National awards. Czechoslovakia, the family leaves Theatre, transferring to Broadway. – Squaring the Circle performed on Zlin for Singapore. Another Moon Called Earth TV. 1942 – Four year old Tomas and his performed on TV. 1985 – His screenplay of Brazil, co- mother and brother are evacuated 1968 – Enter a Free Man, a reworking of written with Terry Gilliam, receives to India. His father remains A Walk on the Water, staged in an Oscar nomination. behind and later dies in Japanese the West End. 1987 – Writes screenplay for Empire of captivity. -

Real Inspector Hound Synopsis 4 Perceptions

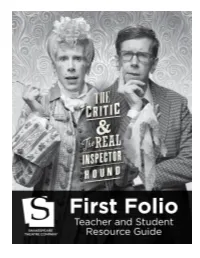

FIRST FOLIO: TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE GUIDE Consistent with the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s central mission to be the leading force in producing and preserving the Table of Contents highest quality classic theatre, the Education Department challenges learners of all ages to explore the ideas, emotions The Critic Synopsis 3 and principles contained in classic texts and to discover the connection between classic theatre and our modern The Real Inspector Hound Synopsis 4 perceptions. We hope that this First Folio: Teacher and Student Resource Guide will prove useful to you while preparing to Who’s Who 5 attend The Critic & The Real Inspector Hound. About the Authors 7 First Folio provides information and activities to help students I, Critic 9 form a personal connection to the play before attending the By Jeffrey Hatcher production. First Folio contains material about the playwrights, their world and their works. Also included are approaches to Tom Stoppard: An Introduction 10 explore the plays and productions in the classroom before and after the performance. Classroom Activities 11 First Folio is designed as a resource both for teachers and Questions for Discussion 16 students. All Folio activities meet the “Vocabulary Acquisition and Use” and “Knowledge of Language” requirements for the Theatre Etiquette 17 grades 8-12 Common Core English Language Arts Standards. We encourage you to photocopy these articles and activities and use them as supplemental material to the text. Enjoy the show! Founding Sponsors The First Folio Teacher and Student Resource Guide for Miles Gilburne and Nina Zolt the 2015-2016 Season was developed by the Shakespeare Theatre Company Education Department: Leadership Support The Beech Street Foundation Director of Education Samantha K. -

The Real Inspector Hound Opened at the Criterion Theatre in London on June 17, 1968

About the play The Real Inspector Hound opened at the Criterion Theatre in London on June 17, 1968. Its opening began the new custom of “Previews.” Originally the dress rehearsal would happen di- rectly before first performance, but Stoppard felt that it was frightening going straight from dress rehearsal to opening night. The producer, Michael Codron, had the idea of having an audience see the show before it opened. So an audi- ence started watching dress rehearsals as well. This helped the actors get used to the audience and allowed Stoppard to make changes before the play was opened. The previews helped build public interest and limited the access of critics until the play was The Real ready. The Real Inspector Hound is presented as a play-within-a-play. The two main characters, Moon and Birdboot, are introduced as theatre critics, which was not Stoppard’s original intention: “I originally conceived a play, Inspector exactly the same play, with simply two members of an audience getting involved in the play-within-the play. But when it comes actually to writing something down which has integral entertain- ment value … it very quickly occurred to me that it would be a Hound lot easier to do it with critics, because you’ve got something known and defined to parody.” Some reviewers have stated that the play is a reply or a challenge to critics, suggesting that they criticize plays, but lack what it takes to perform in one without failing. By Tom Stoppard Stoppard has stated that the main focus of all his plays is to entertain. -

The Actual Versus the Fictional in Betrayal, the Real Thing and Closer

The Actual versus the Fictional in Betrayal, The Real Thing and Closer by Johanna Alida Krüger submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Literature and Philosophy In the subject THEORY OF LITERATURE at the University of South Africa Supervisor: Prof Marisa Keuris November 2014 Student number: 4667-829-8 I declare that “The Actual versus the Fictional in Betrayal, The Real Thing and Closer” is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ________________________ _____________________ JA Krüger DATE i ABSTRACT: Although initially dismissed as superficial, Harold Pinter’s Betrayal, Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing, and Patrick Marber’s Closer use the theme of marital betrayal as a trope to investigate metatheatrical and epistemological issues. This study aims to demonstrate how these three plays define and explore the concept of authenticity within the fictional as well as the actual world; how arbitrary the construction and mediation of the characters’ identities are, not only from their own perspective, but also from the audience’s; the significance of the audience’s role in these plays and how issues of authenticity, fictionality and dishonesty impact on a genre that depends on illusion. This study intends to provide a new interpretation of these three texts through an analysis drawn from postmodern and poststructuralist theories, concerning the concept of authenticity within art and language. This study finds that the fictional worlds in these plays are created through mediation, which includes everyday language as well as complex works of art.