On the Microscope As an Aid to the Study of Biology in Entomology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R. P. LANE (Department of Entomology), British Museum (Natural History), London SW7 the Diptera of Lundy Have Been Poorly Studied in the Past

Swallow 3 Spotted Flytcatcher 28 *Jackdaw I Pied Flycatcher 5 Blue Tit I Dunnock 2 Wren 2 Meadow Pipit 10 Song Thrush 7 Pied Wagtail 4 Redwing 4 Woodchat Shrike 1 Blackbird 60 Red-backed Shrike 1 Stonechat 2 Starling 15 Redstart 7 Greenfinch 5 Black Redstart I Goldfinch 1 Robin I9 Linnet 8 Grasshopper Warbler 2 Chaffinch 47 Reed Warbler 1 House Sparrow 16 Sedge Warbler 14 *Jackdaw is new to the Lundy ringing list. RECOVERIES OF RINGED BIRDS Guillemot GM I9384 ringed 5.6.67 adult found dead Eastbourne 4.12.76. Guillemot GP 95566 ringed 29.6.73 pullus found dead Woolacombe, Devon 8.6.77 Starling XA 92903 ringed 20.8.76 found dead Werl, West Holtun, West Germany 7.10.77 Willow Warbler 836473 ringed 14.4.77 controlled Portland, Dorset 19.8.77 Linnet KC09559 ringed 20.9.76 controlled St Agnes, Scilly 20.4.77 RINGED STRANGERS ON LUNDY Manx Shearwater F.S 92490 ringed 4.9.74 pullus Skokholm, dead Lundy s. Light 13.5.77 Blackbird 3250.062 ringed 8.9.75 FG Eksel, Belgium, dead Lundy 16.1.77 Willow Warbler 993.086 ringed 19.4.76 adult Calf of Man controlled Lundy 6.4.77 THE DIPTERA (TWO-WINGED FLffiS) OF LUNDY ISLAND R. P. LANE (Department of Entomology), British Museum (Natural History), London SW7 The Diptera of Lundy have been poorly studied in the past. Therefore, it is hoped that the production of an annotated checklist, giving an indication of the habits and general distribution of the species recorded will encourage other entomologists to take an interest in the Diptera of Lundy. -

Ecological Survey of Land at Beesley Green, Salford, Greater Manchester

Peel Investments (North) Ltd ECOLOGICAL SURVEY OF LAND AT BEESLEY GREEN, SALFORD, GREATER MANCHESTER DRAFT V1 SEPTEMBER 2013 ESL (Ecological Services) Ltd, 1 Otago House, Allenby Business Village, Crofton Road, Lincoln, LN3 4NL Ecological Survey of Land at Beesley Green, Salford, Greater Manchester SCS.PH Peel Investments (North) Ltd DOCUMENT CONTROL TITLE: Ecological Survey of Land at Beesley Green, Salford, Greater Manchester VERSION: Draft V1 DATE: September 2013 ISSUED BY: Brian Hedley AUTHORS: Brian Hedley, Emily Cook, Pete Morrell, Jackie Nicholson and Andy Jukes CHECKED BY: Andrew Malkinson APPROVED BY: Vanessa Tindale ISSUED TO: Peel Investments (North) Ltd Peel Dome The Trafford Centre Manchester M17 8PL This report has been prepared by ESL with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, within the terms of the contract with the Client. The report is confidential to the Client. ESL accepts no responsibility of whatever nature to third parties to whom this report may be made known. No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior written approval of ESL. ESL (Ecological Services) Ltd, 1 Otago House, Allenby Business Village, Crofton Road, Lincoln, LN3 4NL Ecological Survey of Land at Beesley Green, Salford, Greater Manchester SCS.PH Peel Investments (North) Ltd CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 INITIAL SCOPING STUDY 1 2.1 Desk-based Study 1 2.2 Walkover Survey 3 2.3 Summary of Walkover and Recommendations for Further Survey 4 3 HABITATS, PLANT COMMUNITIES AND SPECIES 6 3.1 Survey Methods 6 3.2 Results 6 3.3 Discussion -

Dipterists Forum

BULLETIN OF THE Dipterists Forum Bulletin No. 76 Autumn 2013 Affiliated to the British Entomological and Natural History Society Bulletin No. 76 Autumn 2013 ISSN 1358-5029 Editorial panel Bulletin Editor Darwyn Sumner Assistant Editor Judy Webb Dipterists Forum Officers Chairman Martin Drake Vice Chairman Stuart Ball Secretary John Kramer Meetings Treasurer Howard Bentley Please use the Booking Form included in this Bulletin or downloaded from our Membership Sec. John Showers website Field Meetings Sec. Roger Morris Field Meetings Indoor Meetings Sec. Duncan Sivell Roger Morris 7 Vine Street, Stamford, Lincolnshire PE9 1QE Publicity Officer Erica McAlister [email protected] Conservation Officer Rob Wolton Workshops & Indoor Meetings Organiser Duncan Sivell Ordinary Members Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD [email protected] Chris Spilling, Malcolm Smart, Mick Parker Nathan Medd, John Ismay, vacancy Bulletin contributions Unelected Members Please refer to guide notes in this Bulletin for details of how to contribute and send your material to both of the following: Dipterists Digest Editor Peter Chandler Dipterists Bulletin Editor Darwyn Sumner Secretary 122, Link Road, Anstey, Charnwood, Leicestershire LE7 7BX. John Kramer Tel. 0116 212 5075 31 Ash Tree Road, Oadby, Leicester, Leicestershire, LE2 5TE. [email protected] [email protected] Assistant Editor Treasurer Judy Webb Howard Bentley 2 Dorchester Court, Blenheim Road, Kidlington, Oxon. OX5 2JT. 37, Biddenden Close, Bearsted, Maidstone, Kent. ME15 8JP Tel. 01865 377487 Tel. 01622 739452 [email protected] [email protected] Conservation Dipterists Digest contributions Robert Wolton Locks Park Farm, Hatherleigh, Oakhampton, Devon EX20 3LZ Dipterists Digest Editor Tel. -

Millichope Park and Estate Invertebrate Survey 2020

Millichope Park and Estate Invertebrate survey 2020 (Coleoptera, Diptera and Aculeate Hymenoptera) Nigel Jones & Dr. Caroline Uff Shropshire Entomology Services CONTENTS Summary 3 Introduction ……………………………………………………….. 3 Methodology …………………………………………………….. 4 Results ………………………………………………………………. 5 Coleoptera – Beeetles 5 Method ……………………………………………………………. 6 Results ……………………………………………………………. 6 Analysis of saproxylic Coleoptera ……………………. 7 Conclusion ………………………………………………………. 8 Diptera and aculeate Hymenoptera – true flies, bees, wasps ants 8 Diptera 8 Method …………………………………………………………… 9 Results ……………………………………………………………. 9 Aculeate Hymenoptera 9 Method …………………………………………………………… 9 Results …………………………………………………………….. 9 Analysis of Diptera and aculeate Hymenoptera … 10 Conclusion Diptera and aculeate Hymenoptera .. 11 Other species ……………………………………………………. 12 Wetland fauna ………………………………………………….. 12 Table 2 Key Coleoptera species ………………………… 13 Table 3 Key Diptera species ……………………………… 18 Table 4 Key aculeate Hymenoptera species ……… 21 Bibliography and references 22 Appendix 1 Conservation designations …………….. 24 Appendix 2 ………………………………………………………… 25 2 SUMMARY During 2020, 811 invertebrate species (mainly beetles, true-flies, bees, wasps and ants) were recorded from Millichope Park and a small area of adjoining arable estate. The park’s saproxylic beetle fauna, associated with dead wood and veteran trees, can be considered as nationally important. True flies associated with decaying wood add further significant species to the site’s saproxylic fauna. There is also a strong -

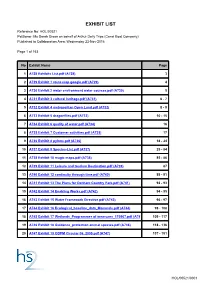

Exhibit List

EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 1 of 163 No Exhibit Name Page 1 A728 Exhibits List.pdf (A728) 3 2 A729 Exhibit 1 route map google.pdf (A729) 4 3 A730 Exhibit 2 water environment water courses.pdf (A730) 5 4 A731 Exhibit 3 cultural heritage.pdf (A731) 6 - 7 5 A732 Exhibit 4 metropolitan Open Land.pdf (A732) 8 - 9 6 A733 Exhibit 5 dragonflies.pdf (A733) 10 - 15 7 A734 Exhibit 6 quality of water.pdf (A734) 16 8 A735 Exhibit 7 Customer activities.pdf (A735) 17 9 A736 Exhibit 8 pylons.pdf (A736) 18 - 24 10 A737 Exhibit 9 Species-List.pdf (A737) 25 - 84 11 A738 Exhibit 10 magic maps.pdf (A738) 85 - 86 12 A739 Exhibit 11 Leisure and tourism Destination.pdf (A739) 87 13 A740 Exhibit 12 continuity through time.pdf (A740) 88 - 91 14 A741 Exhibit 13 The Plans for Denham Country Park.pdf (A741) 92 - 93 15 A742 Exhibit 14 Enabling Works.pdf (A742) 94 - 95 16 A743 Exhibit 15 Water Framework Directive.pdf (A743) 96 - 97 17 A744 Exhibit 16 Ecological_baseline_data_Mammals.pdf (A744) 98 - 108 18 A745 Exhibit 17 Wetlands_Programmes of measures_170907.pdf (A745) 109 - 117 19 A746 Exhibit 18 Guidance_protection animal species.pdf (A746) 118 - 136 20 A747 Exhibit 19 ODPM Circular 06_2005.pdf (A747) 137 - 151 HOL/00521/0001 EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 2 of 163 No Exhibit -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

Proceedings of the United States National Museum SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION . WASHINGTON, D.C. Volume 121 1967 Number 3569 SOLDIER FLY LARVAE IN AMERICA NORTH OF MEXICO ' By Max W. McFadden ^ The Stratiomyidae or soldier flies are represented in America north of Mexico by approximately 237 species distributed through 37 genera. Prior to this study, larvae have been described for only 21 species representmg 15 genera. In addition to the lack of adequate descriptions and keys, classification has seldom been attempted and a phylogenetic treatment of the larvae has never been presented. The present study has been undertaken with several goals in mind: to rear and describe (1) as many species as possible; (2) to redescribe all previously described larvae of North American species; and (3), on the basis of larval characters, to attempt to define various taxo- nomic units and show phylogenetic relationships withm the family and between it and other closely related familes. Any attempt to establish subfamilial and generic lunits must be regarded as tentative. This is especially true in the present study since larvae of so many species of Stratiomyidae remain unknown. Undoubtably, as more species are reared, changes mil have to be made in keys and definitions of taxa. The keys have been prepared chiefly for identification of last mstar larvae. If earher mstars are known, they either have been 1 Modified from a Ph. D. dissertation submitted to the University of Alberta E(hnonton, Canada. ' 2 Entomology Research Division, U.S. Dept. Agriculture, Tobacco Insects Investigations, P.O. Box 1011, Oxford, N.C. 27565. : 2 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM vol. -

The Annals of Scottish Natural History," 1901, As Simon's Chernes Phaleratus, a Form That Has Not Yet Occurred in Scotland

The Annals OF Scottish Natural History A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE . WITH WHICH IS INCORPORATED Q EDITED BY J. A. HARVIE-BROWN, F.R.S.E., F.Z.S MEMBER OF THE BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION JAMES W. H. TRAIL, M.A., M.D., F.R.S., F.L.S. PROFESSOR OF BOTANY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN WILLIAM EAGLE CLARKE, F.L.S., F.R.S.E. KEEPER OF THE NATURAL HISTORY DEPARTMENT, THE ROYAL SCOTTISH MUSEUM, EDINBURGH EDINBURGH DAVID DOUGLAS, CASTLE STREET LONDON: R. H. PORTER, 7 PRINCES ST., CAVENDISH SQUARE The Annals of Scottish Natural History No. 69] 1909 [JANUARY ON THE OCCURRENCE OF EVERSMANN'S WARBLER (PHYLLOSCOPUS BOREALIS (BLASIUS)) AT FAIR ISLE: AN ADDITION TO THE BRITISH FAUNA. By WM. EAGLE CLARKE, F.R.S.E., F.L.S. ON the 28th of September last, while in search of migra- tory birds at Fair Isle, I put up from a patch of potatoes, where it was hiding, a dark-coloured Willow Warbler, which I at once suspected belonged to some species I had never before seen in life. I was fortunate enough to secure the bird, and congratulated myself, as I contemplated its out- stretched wings each with a conspicuous single bar and its well-defined, pale, superciliary stripe, on the capture of the third British example of the Greenish Willow Warbler (Ph. viridanus). On my return to Edinburgh, however, I was agreeably surprised to find that my bird was undoubtedly an example of Eversmann's Warbler (Ph. borealis] a bird which had not hitherto been detected in Britain. -

(Other Than Moths) Attracted to Light

Insects (other than moths) attracted to light Prepared by Martin Harvey for BENHS workshop on 9 December 2017 Although light-traps go hand-in-hand with catching and recording moths, a surprisingly wide range of other insects can be attracted to light and appear in light-traps on a regular or occasional basis. The lists below show insects recorded from light-traps of various kinds, mostly from southern central England but with some additions from elsewhere in Britain, and based on my records from the early 1990s to date. Nearly all are my own records, plus a few of species that I have identified for other moth recorders. The dataset includes 2,446 records of 615 species. (See the final page of this document for a comparison with another list from Andy Musgrove.) This isn’t a rigorous survey: it represents those species that I have identified and recorded in a fairly ad hoc way over the years. I record insects in light-traps fairly regularly, but there are of course biases based on my taxonomic interests and abilities. Some groups that come to light regularly are not well-represented on this list, e.g. chironomid midges are missing despite their frequent abundance in light traps, Dung beetle Aphodius rufipes there are few parasitic wasps, and some other groups such as muscid © Udo Schmidt flies and water bugs are also under-represented. It’s possible there are errors in this list, e.g. where light-trapping has been erroneously recorded as a method for species found by day. I’ve removed the errors that I’ve found, but I might not yet have found all of them. -

DIPTERON Akceptacja: 29.11.2019 Bulletin of the Dipterological Section of the Polish Entomological Society Wrocław 04 XII 2019

Biuletyn Sekcji Dipterologicznej Polskiego Towarzystwa Entomologicznego ISSN 1895 - 4464 Tom 35: 118-131 DIPTERON Akceptacja: 29.11.2019 Bulletin of the Dipterological Section of the Polish Entomological Society Wrocław 04 XII 2019 FAUNISTIC RECORDS OF SOME DIPTERA FAMILIES FROM THE BABIA GÓRA MASSIF IN POLAND ZAPISKI FAUNISTYCZNE DOTYCZĄCE NIEKTÓRYCH RODZIN MUCHÓWEK (DIPTERA) Z MASYWU BABIEJ GÓRY W POLSCE DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3559211 1 2 2 3 JOZEF OBOŇA , LIBOR DVOŘÁK , KATEŘINA DVOŘÁKOVÁ , JAN JEŽEK , 4 5 6 TIBOR KOVÁCS , DÁVID MURÁNYI , IWONA SŁOWIŃSKA , 7 8 1 JAROSLAV STARÝ , RUUD VAN DER WEELE , PETER MANKO 1 Department of Ecology, Faculty of Humanities and Natural Sciences, University of Prešov, 17. novembra 1, SK – 081 16 Prešov, Slovakia; e-mails: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Tři Sekery 21, CZ – 353 01 Mariánské Lázně, Czech Republic; e-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] 3 National Museum in Prague (Natural History Museum), Department of Entomology, Cirkusová 1740, CZ – 193 00 Praha 9 – Horní Počernice, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected] 4 Mátra Museum of the Hungarian Natural History Museum, Kossuth Lajos u. 40, H – 3200 Gyöngyös, Hungary; e-mail: [email protected] 5 Plant Protection Institute, centre for Agricultural research, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Herman Ottó 15. H – 1022, and Hungarian Natural History Museum, Baross u. 13, H – 1088 Budapest, Hungary; e-mails: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 6 Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Hydrobiology, University of Łódź, Banacha 12/16, PL – 90-237 Łódź, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] 7 Neklanova 7, CZ – 779 00 Olomouc-Nedvězí et Silesian Museum, Nádražní okruh 31, CZ – 746 01 Opava, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected] 8 Kloosterlaan 6, NL – 4111 LG, Zoelmond, the Netherlands; e-mail: [email protected] 118 ABSTRACT. -

Checklist of Lithuanian Diptera

NAUJOS IR RETOS LIETUVOS VABZDŽIŲ RŪŠYS. 27 tomas 105 NEW DATA ON SEVERAL DIPTERA FAMILIES IN LITHUANIA ANDRIUS PETRAŠIŪNAS1, ERIKAS LUTOVINOVAS2 1Department of Zoology, Vilnius University, M. K. Čiurlionio 21, LT-03101 Vilnius, Lithuania. E-mail: [email protected] 2Nature Research Centre, Akademijos 2, LT-08412 Vilnius, Lithuania. E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] Introduction The latest list of Lithuanian Diptera included 3311 species (Pakalniškis et al., 2006) and later publications during the past nine years added about 220 more, mainly from the following families: Nematocera: Limoniidae and Tipulidae (Podėnas, 2008), Trichoceridae (Petrašiūnas & Visarčuk, 2007; Petrašiūnas, 2008), Chironomidae (Móra & Kovács, 2009), Bolitophilidae, Keroplatidae, Mycetophilidae and Sciaridae (Kurina et al., 2011); Brachycera: Asilidae (Lutovinovas, 2012a), Syrphidae (Lutovinovas, 2007; 2012b; Lutovinovas & Kinduris, 2013), Pallopteridae (Lutovinovas, 2013), Ulidiidae (Lutovinovas & Petrašiūnas, 2013), Tephritidae (Lutovinovas, 2014), Fanniidae and Muscidae (Lutovinovas, 2007; Lutovinovas & Rozkošný, 2009), Tachinidae (Lutovinovas, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2012c). Fauna of only the few Diptera families in Lithuania (out of 90 families recorded) is studied comparatively better (e.g. Agromyzidae, Limoniidae, Simuliidae, Syrphidae, Tipulidae, Tachinidae), with majority of the families getting weaker or only sporadic attention, if at all. New species are being recorded every time and more effort is devoted, proving that there is still much to do in Diptera research in Lithuania. The following publication provides new data on fifteen Diptera families in Lithuania with most attention paid to several anthophilous families (e.g. Bombyliidae, Conopidae and Stratiomyidae). Material and Methods Most specimens were caught by sweeping the vegetation and the few others were identified from photographs. -

Species List 21/11/2014 1

Dams To Darnley CP Species List 21/11/2014 1 Group Species Common Name Earliest Latest No. Recs acarine (mite) Aceria nalepai 2006 2006 1 acarine (mite) Aceria populi 2010 2010 1 acarine (mite) Eriophyes inangulis 2006 2006 1 acarine (mite) Eriophyes laevis 2008 2008 1 amphibian Bufo bufo Common Toad 1998 2013 14 amphibian Lissotriton helveticus Palmate Newt 2010 2013 12 amphibian Lissotriton vulgaris Smooth Newt 2010 2010 3 amphibian Rana temporaria Common Frog 1996 2013 58 annelid Erpobdellidae leech 2005 2005 1 annelid Oligochaeta a worm 2005 2005 1 bird Accipiter nisus Sparrowhawk 2013 2013 1 bird Acrocephalus schoenobaenus Sedge Warbler 1992 2014 13 bird Actitis hypoleucos Common Sandpiper 1957 2014 8 bird Aegithalos caudatus Long-tailed Tit 1993 2004 7 bird Alauda arvensis Skylark 2003 2004 3 bird Alcedo atthis Kingfisher 1993 2014 22 bird Anas acuta Pintail 1983 1983 1 bird Anas crecca Teal 2003 2013 20 bird Anas penelope Wigeon 1998 2013 11 bird Anas platyrhynchos Mallard 1997 2013 54 bird Anas querquedula Garganey 1982 1982 1 bird Anas strepera Gadwall 1979 2013 15 bird Anser anser Greylag Goose 2004 2004 2 bird Anthus pratensis Meadow Pipit 1982 2013 3 bird Anthus trivialis Tree Pipit 1992 1992 1 bird Apus apus Swift 1982 2014 11 bird Apus melba Alpine Swift 1992 1992 1 bird Ardea cinerea Grey Heron 1990 2014 52 bird Arenaria interpres Turnstone 1911 1981 4 bird Asio otus Long-eared Owl 2004 2004 1 bird Aythya ferina Pochard 2003 2004 11 bird Aythya fuligula Tufted Duck 1999 2013 66 bird Aythya marila Scaup 1900 2013 12 Dams To Darnley CP Species List 21/11/2014 2 Group Species Common Name Earliest Latest No. -

Soldierflies in VC55

LEICESTERSHIRE ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY Provisional status of Soldierflies (Stratiomyidae) in VC55 Ray Morris Odontomyia argentata (Graham Calow) LESOPS 33 (April 2017) ISSN 0957 - 1019 16 Hinckley Road, Dadlington CV13 6HU [email protected] LESOPS 33 (2017) Soldierflies 2 Introduction The flies (Diptera) are often considered to be difficult for the amateur to study. Perhaps the main exception is the Syrphidae (hoverflies) as many are easily recognised from their behaviour, bright coloration and abdominal markings. Even so care has to be taken with many of the species. The flies that constitute the “Larger Brachycera” share two common wing features: anal veins that converge (Figure 1a) and veins that fan out to the edge of the wing (Figure 1b). Among this grouping are the Stratiomyidae (soldierflies) which usually can be readily identified as a family by their well-defined discal cell (Figure 1c) although some, e.g. Pachygaster, may not show this so well. 1c: Small central well- defined discal cell 1a: Anal veins converging towards wing edge 1b: Veins fanning out towards wing edge Figure 1: Typical wing of Stratiomyidae Availability of an excellent user-friendly key (Stubbs & Drake, 2014) enables identification of soldierflies to be achieved relatively easily although some sort of magnification is recommended to aid recognition of diagnostic characters. Most importantly, the soldierflies are a small group and should appeal to those who wish to extend their entomological interest without being burdened by a large number of species to come to terms with. In Britain there are 48 species regarded as being resident and of those 33 have been recorded in VC55 (Leicestershire & Rutland) to the end of 2016.