User Experience Analysis of Qutb Shahi Tombs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

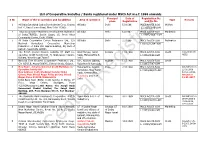

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Malaysian Shi'ites Ziyarat in Iran and Iraq (Cultura. Vol. X, No. 1 (2013))

CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXIOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2014 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 1 2014 Vol XI No 1 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contempo rary world. CULTURE AND AXIOLOGY CULTURE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY INTERNATIONAL www.peterlang.com CULTURA 2014_265846_VOL_11_No1_GR_A5Br.indd.indd 1 14.05.14 17:43 CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE AND AXIOLOGY Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of Culture and Axiology E-ISSN (Online): 2065-5002 ISSN (Print): 1584-1057 Advisory Board Prof. Dr. David Altman, Instituto de Ciencia Política, Universidad Catolica de Chile, Chile Prof. Emeritus Dr. Horst Baier, University of Konstanz, Germany Prof. Dr. David Cornberg, University Ming Chuan, Taiwan Prof. Dr. Paul Cruysberghs, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium Prof. Dr. Nic Gianan, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Philippines Prof. Dr. Marco Ivaldo, Department of Philosophy “A. Aliotta”, University of Naples “Federico II”, Italy Prof. Dr. Michael Jennings, Princeton University, USA Prof. Dr. Maximiliano E. Korstanje, John F. Kennedy University, Buenos Aires, Argentina Prof. Dr. Richard L. Lanigan, Southern Illinois University, USA Prof. Dr. Christian Lazzeri, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense, France Prof. Dr. Massimo Leone, University of Torino, Italy Prof. -

The Crafts and Textiles of Hyderabad and Telangana 11 Days/10 Nights

The Crafts and Textiles of Hyderabad and Telangana 11 Days/10 Nights Activities Overnight Day 1 Fly U.S. to Hyderabad. Upon arrival, you will be transferred to Hyderabad your hotel by private car. Day 2 The city of Hyderabad was constructed in 1591 by King Hyderabad Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah of the Qutb Shahi dynasty, which ruled this region of the Deccan plateau from 1507 to 1687. During this time, the Sultanate faced numerous incursions by the Mughals and the Hindu Marathas. In 1724, the Mughal governor of the Deccan arrived to govern the city. His official title was the Nizam- ul-Muluk, or Administrator of the Realm. After the death of Emperor Aurangzeb, he declared his independence and established the Asaf Jahi dynasty of Nizams. The Nizams of Hyderabad were known for their tremendous wealth, which came from precious gems mined in nearby Golconda (see Day 3), the area's natural resources, a vibrant pearl trade, agricultural taxes and friendly cooperation with the British. Much of the architecture still existing in Hyderabad thus dates from the reigns of the Qutb Shahi Sultans or the Nizams. European influences were introduced by the British in the 19th and 20th centuries. At the center of old Hyderabad sits the Charminar, or "four towers," which dates to 1591 and is surrounded by a lively bazaar and numerous mosques and palaces. This morning we will enjoy a leisurely walk through the area. We will stop to admire the colorful tile mosaics found inside the Badshahi Ashurkhana. This Royal House of Mourning was built in 1595 as a congregation hall for Shia Muslims during Muharram. -

India Tier 1 Cities Mumbai Delhi NCR Bangalore Chennai Hyderabad Pune

RESEARCH CITY PROFILES India Tier 1 Cities Mumbai Delhi NCR Bangalore Chennai Hyderabad Pune Mumbai [Bombay] Mumbai is the most populous city in India, and the fourth most populous city in the world, It lies on the west coast of India and has a deep natural harbour. In 2009, Mumbai, the capital of the state of Maharashtra, was named an alpha world city. It is also the wealthiest city in India, and has the highest GDP of any city in South, West or Central Asia. Area: City - 603 sq. km. | Metro: 4,355 sq. km. Population: ~20.5 million Literacy Levels: 74% Climate: Tropical Wet & Dry (moderately hot with high levels of humidity) – mean average temperature of 32oC in summers and 30oC in winters; average rainfall: 242.2 mm 360 institutions for higher education Extremely well connected by rail (Junction), road and air (International Airport) and rapid transit systems Main Sectors: Wide ranging including Banking, Financial Services and Insurance, Pharmaceuticals, Biotechnology, IT and ITeS, Electronics & Engineering, Auto, Oil and Gas, FMCG, Gems & Jewellery, Textiles City GDP: $ 209 billion 27,500+ IT-ready graduates each year | IT ready population of 500,000+ ~850 STPI registered companies; 9 IT Special Economic Zones Key IT Hubs: Nariman Point, Worli, Lower Parel, Prabhadevi, BKC, Kalina, Andheri, Jogeshwari, Malad, Goregaon, Powai, LBS Marg, Thane, Navi Mumbai CITY EVOLUTION Mumbai is built on what was once an archipelago of seven islands: Bombay Island, Parel, Mazagaon, Mahim, Colaba, Worli, and Old Woman's Island (also known as Little Colaba). It is not exactly known when these islands were first inhabited. -

A Reading from Shaikpet Sarai Qutb Shahi, Hyderabad

hyderabad | Sriganesh Rajendran A READING FROM SHAIKPET SARAI QUTB SHAHI, HYDERABAD Serai: The usual meaning in India is that of a building for the accommodation of travellers with their pack-animals; consisting of an enclosed yard with chambers around it. (Hobson-Jobson, 1903) A large building for the accommodation of travellers, common in Eastern countries. The word is Persian and means in that language, ‘a place, the king’s court, a large edifice’; hence karavan-serai, by corruption caravanserie, i.e. place of rest of caravans. The erection of these buildings is considered highly meritorious by Hindus as well as Mohammedans, who frequently endow them with rents for their support. (The Penny Cyclopedia of The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Vol XXI. London. 1829) Towards B 9 idar 4 5 10 5 A 3 12 7 8 2 13 Towards 11 6 Machilipatnam 1 34 landscape 52 | 2017 hyderabad | he historic reign of the Qutb Shahi dynasty/Golconda Sultanate (1512- T1687) inherited a complex terrain of hillocks and fractures as the settings for their architecture. Judicious interpretation of the natural landscape led Shaikpet Mosque (c. 1978) to the siting of trade routes, fortifications, tomb complexes, water reservoirs, Source: dome.mit.edu percolation ponds, stepped wells, aqueducts and subterranean conveyance sys- Recent conservation works by Government of tems, pleasure gardens, orchards and water distribution mechanisms. Some of Telangana included structural restoration and these systems lie in close proximity to erstwhile settlements or remnant his- protection from encroachments. toric building complexes, while others are found today in the midst of dense SHAIKPET SARAI modern-day settlements. -

Fairs and Festivals During the Qutub Shahi Sultans in Golconda M.Raju M.A

International Journal of Research e-ISSN: 2348-6848 p-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 05 Issue 04 February 2018 Fairs and Festivals during the Qutub Shahi Sultans in Golconda M.Raju M.A. (HISTORY) Abstract: subjects.He took keen interest in the The Golconda Kingdom came into diffusion of learning and patronised many existence after the disintegration of the Hindu scholars and poets, which also helped Bahmani Kingdom in 1518 A.D. Qutb Shahi him in uniting people of the different castes Sultans of Golconda ruled the Andhra and creeds. Out of affection for him, his Desha far nearly two centuries i.e., from Hindu subjects called him ‘Malik Ibhiram’, 1518 to 1687 A.D. Golconda was a vast ‘Vighuram’ or ‘Ibharamudu’. kingdom with fertile land and rich minerals The most outstanding personality resources, besides the agricultural land and among the Qutb Shahi rulers was that of forests. Golconda was blessed with Muhammed Quli Qutb Shah. (1580-1612 A. lucrative mines and other minerals like D), the fifth Qutb Shahi ruler of Golconda. pearls, diamonds, coal, agates, shabbier He was the most enlightened King of the etc. Qutb Shahi Sultans cultivated many Qutb Shah house. He was a versatile genius cultures in the Deccan region and they have a great architect, the founder of the well- respected all local traditions, customs, planned city of Hyderabad, a great poet of literature etc. the Dakhni and Persian, and the ruler of great tolerance for all religions The local Introduction: language, Telugu received encouragement from him. The Telugu poets and prose The contribution of Qutb Shahi Sultans writers were munificently encouraged and to the Socio-Economic and political rewarded by him. -

Etiquettes of Ziyarat

ETIQUETTES OF ZIYARAT WHAT IS ZIYARAT? Ziyarat basically means, to visit the Shrines of the Holy Masumeen (as) or any other holy personality with proximity to ahlulbayt (as). The Holy Prophet (saw) & Imams (as) have highly emphasized the importance of Ziyarat, in order to enable the follower to come closer to the Masumeen, to learn from their character and thereby improve their lives. In order for the Za’er (Visitor) to make his trip successful he needs to ask & understand several issues: HOW DOES ZIYARAT AFFECT OUR LIFE? -Firstly, we go to the Shrine, and we declare and remind ourselves, the HIGH status enjoyed by the Imams: •That they are perfect models •That they are lovers of truth •That they are examples of nobility, justice, of good character, of good minds, or pure thoughts, of pure feelings, of cooperation, of love for humanity, and of all the noble and perfect virtues. -Once we have realized fully, this high position of Imams, we try to provoke feelings in our hearts which God has naturally created, whenever we see beauty we are attracted, whenever we see perfection we are attracted, whenever we see models of goodness, justice & virtue, naturally we seek to follow. -So having reminded ourselves of the virtues of the Imams: •We then pledge our allegiance, •We then swear our obedience, •We then make a covenant to love them, to follow them, and to always keep their pleasure ahead of our pleasure. It is these ideas and themes which are of paramount importance. They should always be on the top of our minds as we participate in the rituals of ziyarat. -

5Bb5d0e237837-1321573-Sample

Notion Press Old No. 38, New No. 6 McNichols Road, Chetpet Chennai - 600 031 First Published by Notion Press 2018 Copyright © Shikha Bhatnagar 2018 All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-1-64429-472-7 This book has been published with all efforts taken to make the material error-free after the consent of the author. However, the author and the publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. No part of this book may be used, reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Contents Foreword vii Ode to Hyderabad ix Chapter 1 Legend of the Founding of the City of Good Fortune, Hyderabad 1 Chapter 2 Legend of the Charminar and the Mecca Masjid 13 Chapter 3 Legend of the Golconda Fort 21 Chapter 4 Legend of Shri Ram Bagh Temple 30 Chapter 5 Legends of Ashurkhana and Moula Ali 52 Chapter 6 Legends of Bonalu and Bathukamma Festivals 62 Chapter 7 Legendary Palaces, Mansions and Monuments of Hyderabad 69 v Contents Chapter 8 Legend of the British Residency or Kothi Residency 81 Chapter 9 Legendary Women Poets of Hyderabad: Mah Laqa Bai Chanda 86 Chapter 10 The Legendary Sarojini Naidu and the Depiction of Hyderabad in Her Poems 92 Conclusion 101 Works Cited 103 vi Chapter 1 Legend of the Founding of the City of Good Fortune, Hyderabad The majestic city of Hyderabad is steeped in history and culture. -

The Urban Morphology of Hyderabad, India: a Historical Geographic Analysis

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2020 The Urban Morphology of Hyderabad, India: A Historical Geographic Analysis Kevin B. Haynes Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Human Geography Commons, and the Remote Sensing Commons Recommended Citation Haynes, Kevin B., "The Urban Morphology of Hyderabad, India: A Historical Geographic Analysis" (2020). Master's Theses. 5155. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/5155 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF HYDERABAD, INDIA: A HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS by Kevin B. Haynes A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Geography Western Michigan University June 2020 Thesis Committee: Adam J. Mathews, Ph.D., Chair Charles Emerson, Ph.D. Gregory Veeck, Ph.D. Nathan Tabor, Ph.D. Copyright by Kevin B. Haynes 2020 THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF HYDERABAD, INDIA: A HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS Kevin B. Haynes, M.S. Western Michigan University, 2020 Hyderabad, India has undergone tremendous change over the last three centuries. The study seeks to understand how and why Hyderabad transitioned from a north-south urban morphological directional pattern to east-west during from 1687 to 2019. Satellite-based remote sensing will be used to measure the extent and land classifications of the city throughout the twentieth and twenty-first century using a geographic information science and historical- geographic approach. -

The Amalgamation of Indo-Islamic Architecture of the Deccan

Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art II 255 THE AMALGAMATION OF INDO-ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE OF THE DECCAN SHARMILA DURAI Department of Architecture, School of Planning & Architecture, Jawaharlal Nehru Architecture & Fine Arts University, India ABSTRACT A fundamental proportion of this work is to introduce the Islamic Civilization, which was dominant from the seventh century in its influence over political, social, economic and cultural traits in the Indian subcontinent. This paper presents a discussion on the Sultanate period, the Monarchs and Mughal emperors who patronized many arts and skills such as textiles, carpet weaving, tent covering, regal costume design, metallic and decorative work, jewellery, ornamentation, painting, calligraphy, illustrated manuscripts and architecture with their excellence. It lays emphasis on the spread of Islamic Architecture across India, embracing an ever-increasing variety of climates for the better flow of air which is essential for comfort in the various climatic zones. The Indian subcontinent has produced some of the finest expressions of Islamic Art known to the intellectual and artistic vigour. The aim here lies in evaluating the numerous subtleties of forms, spaces, massing and architectural character which were developed during Muslim Civilization (with special reference to Hyderabad). Keywords: climatic zones, architectural character, forms and spaces, cultural traits, calligraphic designs. 1 INTRODUCTION India, a land enriched with its unique cultural traits, traditional values, religious beliefs and heritage has always surprised historians with an amalgamation of varying influences of new civilizations that have adapted foreign cultures. The advent of Islam in India was at the beginning of 11th century [1]. Islam, the third great monotheistic religion, sprung from the Semitic people and flourished in most parts of the world. -

Socio Religio Culture During Qutb Shahs Tahseen Bilgrami

Learning Community: 7 (1): 71-76 April, 2016 © 2016 New Delhi Publishers. All rights reserved DOI: 10.5958/2231-458X.2016.00008.7 Socio Religio Culture During Qutb Shahs Tahseen Bilgrami Dy. Director, UGC, Human Resource Development Centre, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The Qutb Shahi dynasty has been considered a “Composite “ of Hindu Muslim religio- social culture. The Qutb Shahi Society were heterogeneous consisting of the people from different lands, religions & sects. They never tried to impose their faith on others. Instead they allowed complete freedom to the people of other religions & sect. Equal opportunities were made available to their subjects in all matters of the State. Even the top positions of the administration were occupied by nobles belonging to different religions & sects. The Qutb Shahi rulers was particularly liberal in patronizing the Telugu poets. His court represented a true picture of the integrated society in which the Hindu & Muslim poets and Scholars had equal status. This policy was not reserved for the matters of state & administration alone but it was extended to the religious institutions also. It was an important feature of the Qutb Shahi Kingdom the Sufis of the period belonged to both the sects of Muslims.Their preaching & practices were not different, they all stood for a liberal outlook.The Qutb Shahs patronized them all. Overlooking the traditions of the period some of the Qutb Shahi ruler had matrimonial alliances with the Sufis. Qutb Shahs used the religious festivals to promote religious harmony in the society which created an atmosphere of brotherhood. -

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks Registered Under MSCS Act W.E.F. 1986 Onwards Principal Date of Registration No

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks registered under MSCS Act w.e.f. 1986 onwards Principal Date of Registration No. S No Name of the Cooperative and its address Area of operation Type Remarks place Registration and file No. 1 All India Scheduled Castes Development Coop. Society All India Delhi 5.9.1986 MSCS Act/CR-1/86 Welfare Ltd.11, Race Course Road, New Delhi 110003 L.11015/3/86-L&M 2 Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development federation All India Delhi 6.8.1987 MSCS Act/CR-2/87 Marketing of India(TRIFED), Savitri Sadan, 15, Preet Vihar L.11015/10/87-L&M Community Center, Delhi 110092 3 All India Cooperative Cotton Federation Ltd., C/o All India Delhi 3.3.1988 MSCS Act/CR-3/88 Federation National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing L11015/11/84-L&M Federation of India Ltd. Sapna Building, 54, East of Kailash, New Delhi 110065 4 The British Council Division Calcutta L/E Staff Co- West Bengal, Tamil Kolkata 11.4.1988 MSCS Act/CR-4/88 Credit Converted into operative Credit Society Ltd , 5, Shakespeare Sarani, Nadu, Maharashtra & L.11016/8/88-L&M MSCS Kolkata, West Bengal 700017 Delhi 5 National Tree Growers Cooperative Federation Ltd., A.P., Gujarat, Odisha, Gujarat 13.5.1988 MSCS Act/CR-5/88 Credit C/o N.D.D.B, Anand-388001, District Kheda, Gujarat. Rajasthan & Karnataka L 11015/7/87-L&M 6 New Name : Ideal Commercial Credit Multistate Co- Maharashtra, Gujarat, Pune 22.6.1988 MSCS Act/CR-6/88 Amendment on Operative Society Ltd Karnataka, Goa, Tamil L 11016/49/87-L&M 23-02-2008 New Address: 1143, Khodayar Society, Model Nadu, Seemandhra, & 18-11-2014, Colony, Near Shivaji Nagar Police ground, Shivaji Telangana and New Amend on Nagar, Pune, 411016, Maharashtra 12-01-2017 Delhi.