Springboks at the Somme: the Making of Delville Wood, 1916

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If You Shed a Tear Part 2

“IF YOU SHED A TEAR" PART 2 Unveiling of the permanent Cenotaph in Whitehall by His Majesty King George V, 11 ovember 1920 THIS SECTIO COVERS THE PROFILES OF OUR FALLE 1915 TO 1917 “IF YOU SHED A TEAR" CHAPTER 9 1915 This was the year that the Territorial Force filled the gaps in the Regular’s ranks caused by the battles of 1914. They also were involved in new campaigns in the Middle East. COPPI , Albert Edward . He served as a Corporal with service number 7898 in the 1st Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment 84th Brigade, 28th Di vision Date of Death: 09/02/1915.His next of kin was given as Miss F. J. Coppin, of "Grasmere," Church Rd., Clacton -on-Sea, Essex. The CD "Soldiers Died in the Great War" shows that he was born in Old Heath & enlisted at Woolwich. Albert was entitled to the British War Medal and the Allied Victory Medal. He also earned the 1914-1915 Star At the outbreak of war, the 1st Battalion were in Khartoum, Sudan. On 20 ov 1907 they had set sail for Malta, arriving there on 27 ov. On 25 Ja n 1911 they went from Malta to Alexandria, arriving in Alexandria on 28 Jan. On 23 Jan 1912 they went from Alexandria to Cairo. In Feb 1914 they went from Cairo to Khartoum, where they were stationed at the outbreak of World War One. In Sept 1914 the 1st B attalion were ordered home, and they arrived in Liverpool on 23 Oct 1914. They then went to Lichfield, Staffs before going to Felixstowe on 17 ov 1914 (they were allotted to 28th Div under Major Gen E S Bulfin). -

The Evolution of British Tactical and Operational Tank Doctrine and Training in the First World War

The evolution of British tactical and operational tank doctrine and training in the First World War PHILIP RICHARD VENTHAM TD BA (Hons.) MA. Thesis submitted for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy by the University of Wolverhampton October 2016 ©Copyright P R Ventham 1 ABSTRACT Tanks were first used in action in September 1916. There had been no previous combat experience on which to base tactical and operational doctrine for the employment of this novel weapon of war. Training of crews and commanders was hampered by lack of vehicles and weapons. Time was short in which to train novice crews. Training facilities were limited. Despite mechanical limitations of the early machines and their vulnerability to adverse ground conditions, the tanks achieved moderate success in their initial actions. Advocates of the tanks, such as Fuller and Elles, worked hard to convince the sceptical of the value of the tank. Two years later, tanks had gained the support of most senior commanders. Doctrine, based on practical combat experience, had evolved both within the Tank Corps and at GHQ and higher command. Despite dramatic improvements in the design, functionality and reliability of the later marks of heavy and medium tanks, they still remained slow and vulnerable to ground conditions and enemy counter-measures. Competing demands for materiel meant there were never enough tanks to replace casualties and meet the demands of formation commanders. This thesis will argue that the somewhat patchy performance of the armoured vehicles in the final months of the war was less a product of poor doctrinal guidance and inadequate training than of an insufficiency of tanks and the difficulties of providing enough tanks in the right locations at the right time to meet the requirements of the manoeuvre battles of the ‘Hundred Days’. -

Three WWI South Africa's Heroes in Delville Wood

Three WWI South Africa’s Heroes in Delville Wood Shocked, shell shocked, bomb-shocked; no matter what kind of shock is experienced, shock drives different men to react differently, especially if the ‘man’ just turned 21 years of age. Young William “Mannie” Faulds from Cradock, South Africa, together with his brother, Paisley, and friends from school days joined up with the South African forces to fight during World War One (WWI). He and his bosom friend and neighbour, Arthur Schooling, enlisted and went everywhere together. Together they fought under command of General Louis Botha during the South West African Campaign and then in Egypt before being deployed to fight in the Battle of the Somme in France. During the Battle of Delville Wood, on the 16th of July 1916, Arthur Schooling was shot and killed in No Man’s Land. Mannie Faulds could do nothing to help his friend and most probably went into shock. On the same day, 16 July, Lieut. Arthur Craig (1st BN B Coy) was also shot and lay wounded close to the body of Arthur Schooling between the Allied and enemy trenches. Three young Springboks, Pte. Mannie Faulds, Pte. Clifford Baker and Pte. Alexander Estment, took matters into their own hands, defied the risk and in broad daylight at 10:30, climbed the barricade and crawled to their severely wounded Lieutenant and piggy-backed (pick-a-back) him to relative safety. Private Baker was badly wounded in the attempt. Lieutenant Craig eventually landed up in the South African Military Hospital in Richmond, England, having been taken to the dressing station and then by stretcher bearers to the hospital at Abberville. -

Copyright © 2016 by Bonnie Rose Hudson

Copyright © 2016 by Bonnie Rose Hudson Select graphics used by permission of Teachers Resource Force. All Rights Reserved. This book may not be reproduced or transmitted by any means, including graphic, electronic, or mechanical, without the express written consent of the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews and those uses expressly described in the following Terms of Use. You are welcome to link back to the author’s website, http://writebonnierose.com, but may not link directly to the PDF file. You may not alter this work, sell or distribute it in any way, host this file on your own website, or upload it to a shared website. Terms of Use: For use by a family, this unit can be printed and copied as many times as needed. Classroom teachers may reproduce one copy for each student in his or her class. Members of co-ops or workshops may reproduce one copy for up to fifteen children. This material cannot be resold or used in any way for commercial purposes. Please contact the publisher with any questions. ©Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com 2 World War I Notebooking Unit The World War I Notebooking Unit is a way to help your children explore World War I in a way that is easy to personalize for your family and interests. In the front portion of this unit you will find: How to use this unit List of 168 World War I battles and engagements in no specific order Maps for areas where one or more major engagements occurred Notebooking page templates for your children to use In the second portion of the unit, you will find a list of the battles by year to help you customize the unit to fit your family’s needs. -

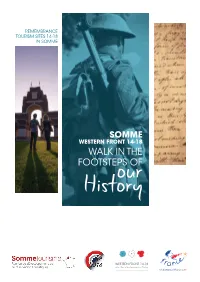

Walk in the Footsteps of Their Elders, and in So Doing to Learn More About Their Own History

REMEMBRANCE toURISM SITES 14-18 IN SOMME SOMME WESTERN FRONT 14-18 WALK IN THE FOOTSTEPSour OF History ATOUT FRANCE 1 MINEFI TONS RECOMMANDÉS (4) MIN_11_0000_RdVFrance_Q Date le 22/06/2011 A NOUS RETOURNER SIGNÉE AVEC VOTRE ACCORD OU VOS CORRECTIONS CYAN MAGENTA JAUNE NOIR JFB ACCORD DATE CRÉATION ÉCHELLE 1/1 - FORMAT D’IMPRESSION 100% PRODUCTION CONSULTANT 12345678910 CLIENT + QUALITÉ* CARRÉ NOIR - 82, bd des Batignolles - 75017 Paris - FRANCE / Tél. : +33 (0)1 53 42 35 35 / Fax : +33 (0)1 42 94 06 78 / Web : www.carrenoir.com JEAN-MARC TODESCHINI SECretarY OF State FOR VETERANS AND REMEMBRANCE Since 2014, France has been fully engaged in the centenary of the Great War, which offers us all the opportunity to come together and share our common history. A hundred years ago, in a spirit of brotherhood, thousands of young soldiers from Great Britain and the countries of the Commonwealth came here to fight alongside us on our home soil. A century later, the scars left on the Somme still bear testimony to the battles of 1916, as do the commemorative sites which attest France’s gratitude to the 420,000 British soldiers who fell in battle, thousands of whom sacri- ficed their lives for this country. In the name of this shared history, whose echo still resonates across the landscape of the Somme, of the brothe- rhood of arms created in the horror of the trenches, and of the memory shared by our two countries, France has a duty to develop and protect the British monuments and cemeteries located in the Somme as well as to extend the warmest possible welcome to tourists visiting the region to reminisce the tragic events of the past century. -

The Western Front, France, April 1916

1 The War Diaries of Dr Charles Molteno ‘Kenah’ Murray Book 4: The Western Front – France 19 April 1916 - 25 December 1917 Edited by Dr Robert Murray Extracts selected and Endnotes by Robert Molteno CONTENTS Arrival at Marseilles – disinfecting the regiments 1 Beauty of the French countryside in spring 3 Off to Northern France 4 First experiences of the front line 4 Battle of the Somme 5 Evacuating the wounded 6 Chaos of battle – Delville Wood 8 ‘One continuous roar – one would think that no living thing could be left’ 10 ‘No more barbarous warfare could possibly have taken place’ 10 ‘This is not fighting, it is cold blooded murder’ 14 What shell fire does 15 The battlefield 16 Under bombardment again – Arras 18 Another gigantic assault on the German lines 18 ‘One continuous and might roar’ 20 Kenah flies over the front line 20 The German High Command takes much better care of its men 21 Our Belgian Allies collapse militarily 22 In the wake of battle 22 Fighting in Belgium – new difficulties 23 The Battle of Ypres 24 Ypres – what happened 25 Superior German air power 26 Enduring – life on the front line 26 Being shelled day after day 28 Cavalry deployed – stupidity of the Higher Command 28 More stupid errors; more divisions flee 29 Arrival at Marseilles – disinfecting the regiments 19 April 1916. The weather has been cold and stormy all the way, sometimes worse than others, but never nice. We are due at Marseilles today. 2 24 April 1916. Arrived at Marseilles on the evening of the 19th. -

Men of Ashdown Forest Who Fell in the First World War and Who Are Commemorated At

Men of Ashdown Forest who fell in the First World War and who are commemorated at Forest Row, Hartfield and Coleman’s Hatch Volume One 1914 - 1916 1 Copyright © Ashdown Forest Research Group Published by: The Ashdown Forest Research Group The Ashdown Forest Centre Wych Cross Forest Row East Sussex RH18 5JP Website: http://www.ashdownforest.org/enjoy/history/AshdownResearchGroup.php Email: [email protected] First published: 4 August 2014 This revised edition: 27 November 2017 © The Ashdown Forest Research Group 2 Copyright © Ashdown Forest Research Group CONTENTS Introduction 4 Index, by surname 5 Index, by date of death 7 The Studies 9 Sources and acknowledgements 108 3 Copyright © Ashdown Forest Research Group INTRODUCTION The Ashdown Forest Research Group is carrying out a project to produce case studies on all the men who died while on military service during the 1914-18 war and who are commemorated by the war memorials at Forest Row and Hartfield and in memorial books at the churches of Holy Trinity, Forest Row, Holy Trinity, Coleman’s Hatch, and St. Mary the Virgin, Hartfield.1 We have confined ourselves to these locations, which are all situated on the northern edge of Ashdown Forest, for practical reasons. Consequently, men commemorated at other locations around Ashdown Forest are not covered by this project. Our aim is to produce case studies in chronological order, and we expect to produce 116 in total. This first volume deals with the 46 men who died between the declaration of war on 4 August 1914 and 31 December 1916. We hope you will find these case studies interesting and thought-provoking. -

Claremen Who Fought in the Battle of the Somme July-November 1916

ClaremenClaremen who who Fought Fought in The in Battle The of the Somme Battle of the Somme July-November 1916 By Ger Browne July-November 1916 1 Claremen who fought at The Somme in 1916 The Battle of the Somme started on July 1st 1916 and lasted until November 18th 1916. For many people, it was the battle that symbolised the horrors of warfare in World War One. The Battle Of the Somme was a series of 13 battles in 3 phases that raged from July to November. Claremen fought in all 13 Battles. Claremen fought in 28 of the 51 British and Commonwealth Divisions, and one of the French Divisions that fought at the Somme. The Irish Regiments that Claremen fought in at the Somme were The Royal Munster Fusiliers, The Royal Irish Regiment, The Royal Irish Fusiliers, The Royal Irish Rifles, The Connaught Rangers, The Leinster Regiment, The Royal Dublin Fusiliers and The Irish Guards. Claremen also fought at the Somme with the Australian Infantry, The New Zealand Infantry, The South African Infantry, The Grenadier Guards, The King’s (Liverpool Regiment), The Machine Gun Corps, The Royal Artillery, The Royal Army Medical Corps, The Royal Engineers, The Lancashire Fusiliers, The Bedfordshire Regiment, The London Regiment, The Manchester Regiment, The Cameronians, The Norfolk Regiment, The Gloucestershire Regiment, The Westminister Rifles Officer Training Corps, The South Lancashire Regiment, The Duke of Wellington's (West Riding Regiment). At least 77 Claremen were killed in action or died from wounds at the Somme in 1916. Hundred’s of Claremen fought in the Battle. -

The Durham Light Infantry and the Somme 1916 Contents

The Durham Light Infantry and The Somme 1916 Contents Part 1: Introduction and Background Notes leading up to the Battle of the Somme. 1.1: Introduction. 1.2: The background to the Battle of the Somme, 1 July – 18 November 1916. 1.3: The Organisation of the Fourth Army, including the composition of Divisions and Brigades in which the DLI Battalions served. 1.4: Battles, Tactical Incidents and Subsidiary Attacks. Part 2: The Battles and Actions in which the Sixteen Battalions of The Durham Light Infantry were involved. 2.1: 1 - 13 July 1916. The Battle of Albert and the Capture of Contalmaison. 2.2: 14 - 17 July 1916. The Battle of Bazentin Ridge. 2.3: 14 July - 3 September 1916. The Battle of Delville Wood. 2.4: 14 July - 7 August 1916. The Battle of Pozières Ridge. 2.5: 3 - 6 September 1916. The Battle of Guillemont. 2.6: 15 - 22 September 1916. The Battle of Flers-Courcelette. 2.7: 25 - 28 September 1916. The Battle of Morval. 2.8: 1 - 18 October 1916. The Battle of Le Transloy Ridges. 2.9: 23 October - 5 November 1916. Fourth Army Operations. 2.10: 13 - 18 November 1916. The Battle of the Ancre. 1 Part 3: The Awards for Distinguished Conduct and Gallantry. 3.1: Notes and analysis of Awards for gallantry on the Somme. 3.2: The Victoria Cross, the Distinguished Service Order and the Military Cross awarded to Officers of the DLI for gallantry on the Somme 1916. 3.2.1: The Victoria Cross. 3.2.2: The Distinguished Service Order. -

Great War in the Villages Project

Great War in the Villages Project Arthur Sturman Arthur was born in 1889 in Eggington, Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire. He was the son of William and Annie Sturman. William was a farm labourer.i By 1911, age 21, he was working as a footman at the Bletchley Park home of Herbert Samuel Leon, the Liberal politician and city financier. ii It has not been possible to ascertain his connection with Moreton Morrell but it is possible he was working at one of the large houses again as a footman. However he enlisted in Rugby, joining the 5 th (Service) Battalion of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, 42 nd Brigade, 14 th (light) Division. He arrived in France on 20 th May 1915 and was by the time of his death he was a corporal, army number 10669. At age 27, he was killed in action on 24 th August 1916 during the Battle of Delville Wood. iii He is remembered Thiepval Memorial and as well as being named on the Moreton Morrell Memorial he is also named and remembered on the Eggington War Memorial where his father and mother lived. 1 Great War in the Villages Project Although no account of the action in which he died has been discovered, the following extracts describes the Battle and concludes that 14 th Light Division of which Arthur’s regiment was a part, took the Wood on 25 th August. Arthur was killed on the 24 th August on the eve of the victory. Extract “The Battle of Delville Wood, 1916 A subsidiary attack of the Somme Offensive, and fought from July 15 until 3 September 1916, the Battle of Delville Wood saw the capture of the wood that had been skirted during the Battle of Bazentin Ridge when Longueval fell to the British on 9 July. -

Bolton Family

! THE BOLTON FAMILY Francis Bolton 1877 – July 1916 Edward Bolton 1879 – April 1917 Henry Thomas (Harry) Bolton 1889 – January 1917 The tragic deaths of these three brothers within nine months of each other must have been devastating for their parents and siblings. Thomas and Ruth Bolton, the parents, had a family of 12 children, nine boys and three girls and seem to have favoured group baptisms: William, Sarah, Ruth, John and Emily were all christened on 4 October 1874; Frederick, Francis and Edward on 16 November 1879; Albert christened individually on 20 April 1887 and finally Henry Thomas, Walter and Arthur on 4 November 1891.The family lived in Red Lion Lane, Amersham Common, the father working as a brewery labourer, probably at Weller’s brewery, Old Amersham. Francis Bolton st Private 22235, 1 Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment Francis Bolton was born about 1877 at his parents’ home in Amersham Common and was baptised on 16 November 1879 in Amersham. In the 1891 Census he was still living at home, aged about 14, with his parents and six siblings. By the time of the 1901 Census Francis was liv ing at 30 Turner Road in Strood, Kent with wife Alice and was working as a general labourer. He was in Paddington in 1911 at 46 Goldney Road. He and Alice had been married for eleven years, but there were no children. Francis was a general labourer for a b uilder. His last known address was in West Kilburn. Francis Bolton enlisted in London, in the 1st Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment as a private, but the date is unknown. -

History Tour.Qxp Layout 1

12-day World War I Historical Tribute Tour to France & Belgium Ypress Lile Amiens Delville Wood “Lest We Forget” Caen Reims Remembering Delville Wood - 1916 Beaches of Remembering Delville Wood - 1916 Normandy Paris Verdun Versailles They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: What’s the plan Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, Day 1: South Africa – Paris Depart South Africa for We will remember them. Included your flight to Paris, France. - Lest We Forget Day 2: Paris Arrive in Paris, meet your local guide at the airport and transfer directly to the Verdun region – • International Flights. the sight of some of the fiercest fighting during The Great War. • 9 nights hotel accommodation. • Daily breakfast. Verdun was the site of a major battle of the First World War. One of the costliest battles of the war, Verdun exemplified the • English speaking tour guide. policy of a "war of attrition" pursued by both sides, which led to an enormous loss of life. Verdun was the strongest point in • All transfers in private coach pre-war France, ringed by a string of powerful forts, including Douaumont and Vaux. By 1916, the salient at Verdun jutted into transfers. the German lines and lay vulnerable to attack from three sides. The historic city of Verdun had been a Gallic fortress before • Transport passes. Roman times and later a key asset in wars against Prussia, and Falkenhayn suspected that the French would throw as many men • Entrance fees and tickets.