Testimony of Daniel Hinkle for the American Association for Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lives Saved Calculations for Seat Belts and Frontal Air Bags This Publication Is Distributed by the U.S

DOT HS 811 206 December 2009 Lives Saved Calculations for Seat Belts and Frontal Air Bags This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The United States Government assumes no liability for its content or use thereof. If trade or manufacturers’ names or products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publication and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. DOT HS 811 206 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Lives Saved Calculations for Seat Belts and Frontal Air Bags December 2009 6. Performing Organization Code NVS-421 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Glassbrenner, Donna, Ph.D., and Starnes, Marc 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Mathematical Analysis Division, National Center for Statistics and Analysis National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 11. Contract or Grant No. NVS-421, 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE. Washington, DC 20590 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Mathematical Analysis Division, National Center for Statistics and Analysis NHTSA Technical Report National Highway Traffic Safety Administration NVS-421, 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE. 14. -

DRIVE PILOT: an Automated Driving System for the Highway Introducing DRIVE PILOT: an Automated Driving System for the Highway Table of Contents

Introducing DRIVE PILOT: An Automated Driving System for the Highway Introducing DRIVE PILOT: An Automated Driving System for the Highway Table of Contents Introduction 4 Validation Methods 36 Our Vision for Automated Driving 5 Integrated Verification Testing 36 The Safety Heritage of Mercedes-Benz 6 Field Operation Testing 38 Levels of Driving Automation 8 Validation of Environmental Perception and Positioning 40 On the Road to Automated Driving: Virtual On-Road Testing 42 Intelligent World Drive on Five Continents 12 Validation of Driver Interaction 44 Final Customer-Oriented On-Road Validation 44 Functional Description of DRIVE PILOT 14 How does DRIVE PILOT work? 16 Security, Data Policy and Legal Framework 46 Vehicle Cybersecurity 46 General Design Rules of DRIVE PILOT 18 Heritage, Cooperation, Continuous Improvement 47 Operational Design Domain 18 Data Recording 48 Object and Event Detection and Response 20 Federal, State and Local Laws and Regulations 49 Human Machine Interface 23 Consumer Education and Training 50 Fallback and Minimal Risk Condition 25 Conclusion 52 Safety Design Rules 26 Safety Process 28 Crashworthiness 30 During a Crash 32 After a Crash 35 Introduction Ever since Carl Benz invented the automobile in 1886, Mercedes-Benz vehicles proudly bearing the three-pointed star have been setting standards in vehicle safety. Daimler AG, the manufacturer of all Mercedes-Benz vehicles, continues to refine and advance the field of safety in road traffic through the groundbreaking Mercedes-Benz “Intelligent Drive” assistance systems, which are increasingly connected as they set new milestones on the road to fully automated driving. 4 Introduction Our Vision for Automated Driving Mercedes-Benz envisions a future with fewer traffic accidents, less stress, and greater enjoyment and productivity for road travelers. -

Holistic Approach for Vehicle Safety at Mercedes-Benz

Alternating between white and black slide layouts via menu bar: Reset the slide back to its Change the slide layout via menu bar: Holistic Approach for Vehicle Safety at Mercedes-Benz Per Lewerenz, Mercedes Benz AG, RD/KSF, VET 2019 Agenda 1. History of Vehicle Safety 2. The Integral Safety Strategy History of Road Accidents Vehicle Safety| Per Lewerenz | Nov 2019 3 Safety Aspects of the Benz Patent Motor Car from 1886 • Comfortable and safe • Easier and safer to operate compared to horse buggies Vehicle Safety| Per Lewerenz | Nov 2019 4 Mercedes-Benz – The Cradle of Vehicle Safety More than 75 Years of Experience in Passenger-Car Safety Development 1939 The „Father of Passive Safety“, Béla Barényi, was employed by Daimler-Benz. 1959 Crumple Zone, Rigid Passenger Cell and Interior Paddings were implemented in series production for the first time. Vehicle Safety| Per Lewerenz | Nov 2019 5 Mercedes-Benz – The Cradle of Vehicle Safety .1959 Crumple Zone . 1978 ABS .1980 Airbag, Belt Tensioner .1989 Automatic Rollover Bar .1995 ESP®, Sidebag .1996 Brake Assist .1997 Sandwich Concept .1998 Windowbag, Adaptive Front Airbag .2002 PRE-SAFE® .2003 Active Light Function .2005 Adaptive Brake Lights, Brake Assist PLUS, NECK-PRO Head Restraint .2006 PRE-SAFE ® Brake, Intelligent Light System .2007 Blind Spot Assist .2008 Reversible Active Bonnet .2009 Attention Assist, Self-Adaptive Belt Force Limiter .2013 PRE-SAFE® Impulse, Beltbag, Active Buckle Lifter .2016 PRE-SAFE® Sound, PRE-SAFE® Impulse Side Vehicle Safety| Per Lewerenz | Nov 2019 6 International -

2021 Sequoia-SR5 Sequoia-SR5 4WD 5.7L V8 6-Speed Automatic

Toyota of Gladstone 19375 SE McLoughlin Blvd. Gladstone OR 97027 503-722-4800 2021 Sequoia-SR5 Sequoia-SR5 4WD 5.7L V8 6-Speed Automatic Model: 7919E VIN: 5TDAY5B13MS186054 Stock: T13995 Engine: 5.7L-V8 Engine Transmission: 6-Speed-Automatic Transmission EXTERIOR INTERIOR Celestial-Silver Metallic Graphite-Leather FUEL ECONOMY PRICE Vehicle Base Model $53,625.00 Total Installed Packages & Accessories $4,698.00 MPG 13MPG 17MPG Delivery Processing and Handling $1,365.00 14 COMBINED CITY HIGHWAY Total MSRP* $59,688.00 INSTALLED PACKAGES & ACCESSORIES 50-State Emissions $0.00 Premium-Package $4,325.00 Premium-Package: includes 8-passenger leather-trimmed seats; heated 10-way power-adjustable driver's seat and 6- way power-adjustable front passenger seat; power reclining and fold-fat third-row seating; Premium Audio with Dynamic Navigation with up to 3-year trial, dynamic auto-dimming rearview mirror with compass and HomeLink® universal transceiver. All-Weather-Floor Liners/ All-Weather Cargo Mat / Door Sill Protector $373.00 All-Weather-Liners, All-Weather Cargo Mat & Door Sill protectors. PREFERRED-OWNER'S PORTFOLIO $0.00 Total Optional Equipment $4,698.00 Vehicle Base Model $53,625.00 Delivery Processing and Handling $1,365.00 FEATURES Mechanical & Performance Engine:-5.7-Liter i-FORCE V8 DOHC 32-Valve with Dual Emission-rating: California Air Resources Board (CARB) Emission Independent Variable Valve Timing with intelligence (VVT-i); 381 Standard: Low Emission Vehicle (LEV) III, Ultra Low Emission hp @ 5600 rpm; 401 lb.-ft. @ 3600 rpm -

Solutions Providers for Ever Better Active and Passive Safety

Solutions providers Where do we come from and what is still in for ever better Active the pipeline? and Passive Safety What is CLEPA? What does CLEPA do? CLEPA - the European Association of Automotive CLEPA is the voice of the Suppliers - brings together over 120 global EU automotive supplier suppliers of car parts, systems and modules industry, linking the sector and more than 20 national trade associations to policy makers. and European sector associations. Key past and future road safety technologies Brake assist Child restraint systems ACC adaptive cruise control Collapsible steering column Adaptive front lights Cruise control Airbags Crumple zone/frame Energy absorption Antilock braking systems Drowsiness alert Anti-skid traction control Electronic stability control Automatic parking Forward collision warning/assist Autonomous valet parking Frontal/lateral/pole impact protection Blind spot detection What is Active and Passive safety? Active safety - refers to Passive safety - refers to safety systems that help avoid components of the vehicle accidents, such as good steering (primarily airbags, seatbelts and and braking but has the last years the physical structure of the been expanded with many new vehicle) that help to protect systems such as forward collision during and after a crash. warning system and autonomous emergency braking. General Safety Regulation (GSR) • Every 3 years the European Commission must make a report to the European Parliament and Council concerning news safety measures, if appropriate. • New measures should -

Technologies for Safety Improvement

Chapter 7 Technologies for safety improvement Taro Sekine Associate Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, College of Science and Technology, Nihon University 7.1 Passenger vehicles This section categorizes by features various technologies for realizing the safety image presented in Chapter 6 and introduces the technologies with respect to each category of vehicle. We also describe the implementation timing for the devices shown in Fig. 1, mainly for passenger vehicles. Areas incorporating safety technologies Range for reducing the number of deaths due to traffic accidents Range for reducing the number of traffic accidents Before accident Immediately before During and immediately after After accident Collision prevention Damage reduction Collision Rescue Notification Support Intervention Automated Collision Notification System Pre-collision Active safety Passive safety safety Preventive Accident avoidance Pre-collision safety Injury reduction Damage mitigation Safety ACC ABS CMBS Collision safety body Emergency alert system LKA TRC E-pretensioner Seatbelt/child seat Energy-sensitive door unlock AFS ESC Airbag system system Multiview camera Pop-up hood Active headrest Figure 1. Areas incorporating safety technologies 7.1.1 Active safety As of 2013, there are approximately 600,000 automobile accidents in Japan per year, and there is ongoing research and development and efforts to spread active safety technologies for preventing automobile accidents through the use of electronics and control technologies. 国際交通安全学ハン��ック_7章e150329名入れ.indd 71 15.3.30 1:43:30 PM 72|Theory (1) Visibility enhancement technologies Today we are seeing the practical use of high- luminosity discharge and LED headlights, which can improve forward visibility at sun- set, at nighttime, and during inclement weather. -

VEHICLE SAFETY Instructions: Use the Arrows Or Swipe Left / Right to Browse Through the Slides

VEHICLE SAFETY Instructions: Use the arrows or swipe left / right to browse through the slides. (The slideshow will autoplay unless you click the PAUSE button.) When you have completed your review of all slides, click on the X in the upper right corner of the presentation to return to your lesson. The terms "active safety" and "passive safety" are simple but important terms in the world of automotive safety. "Active safety" refers to technology assisting in the prevention of a crash and "passive safety" refers to components of the vehicle (primarily airbags, seatbelts and the physical structure of the vehicle) that help to protect occupants during a crash. CRASH AVOIDANCE Crash avoidance systems and devices (such as headlamps, reflectors, lights, signals, mirrors, brakes, steering and suspension systems) help the driver to avoid a collision. DRIVER ASSISTANCE A subset of crash avoidance is driver assistance systems, which help the driver to detect ordinarily hidden obstacles and to control the vehicle. Several driver assistance systems were mentioned in the video, such as automatic braking, adaptive headlights, backup camera, lane departure warnings, etc. Crashworthy systems and devices prevent or reduce the severity of injuries when a crash is imminent or actually happening. Crashworthiness is measured by a structure’s ability to protect its occupants or users during an impact. Much of this research is carried out using crash test dummies. Seatbelts limit the forward motion of an occupant, stretch to slow down the occupant’s deceleration in a crash and prevent occupants being ejected from the vehicle. Headrests protect vehicle occupants from whiplash. -

AIS Template

THE ORIGINAL NEW CAR COST GUIDE Automobile Invoice Service 2620 Barrett Road Gainesville, GA 30507 The Original New Car Cost Guide (ISSN: 1544-9637) is published bi-monthly (JAN, MAR, MAY, JUL, NOV) and monthly (SEP, OCT) by National Auto Research Division Hearst Business Media, 2620 Barrett Road, Gainesville, GA 30507-7901, Thomas D. Cross, President; Robert D. Wilbanks, Treasurer; and Catherine A. Bostron, Secretary. Subscription price is $198.00 per year, volume discounts available. Periodical Postage paid at Gainesville, GA 30501. POSTMASTER, send address changes to Black Book ® Original New Car Cost Guide, PO Box 758, Gainesville, Georgia 30503-0758. © 2016 by Hearst Business Media – ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 2017 KIA SORENTO EFFECTIVE 02-22-17 MAJOR CHANGES FOR 2017: No Major Changes CODE SERIES MODEL INVOICE RETAIL 73212 L 4D SUV FWD ...........................................................................................................................................24705.00 25600.00 73222 LX 4D SUV FWD ...........................................................................................................................................25896.00 26900.00 73422 4D SUV AWD ...........................................................................................................................................27638.00 28700.00 74222 4D SUV FWD V6 .....................................................................................................................................28157.00 29200.00 74422 4D SUV AWD V6 .....................................................................................................................................29899.00 -

Vehicle Extrication Passenger Safety Systems

VEHICLE EXTRICATION Extrication operations on today’s vehicles are significantly different and more dangerous than what we have faced in the past. The government is requiring that auto makers adhere to tougher, more stringent safety standards. These safety standards increase the survivability of passengers that have been involved in an accident, at the same time we are finding that the vehicles manufactured to these newer standards are presenting us with tougher challenges. These vehicles are now being armed with multiple airbags that are controlled by smart computer system which can be extremely dangerous to rescuers and patients during extrication operations. Firefighters will also find that automakers are using more exotic metals to strengthen and reinforce vital structural components. In the past, we have gone to the scene of an extrication knowing that our tools, regardless of the brand, could cut through any vehicle we came up against. Today, however, because of these stronger, more lightweight metals, the tools that we have relied on in the past are having a tougher time cutting through and spreading these metals. Never before has it been so important to understand the capabilities and limitations of our rescue tools. Rescuers will have to find alternative techniques and tools to achieve the same results as in the past. Understanding how vehicles are constructed and knowing what they are constructed of, will allow us to make better decisions on scene Rescuers must also understand that the auto makers are constantly improving on the designs of their safety systems. These changes are happening so quickly, that it would be safe to say that by the time this chapter and volume are published, the material you are reading will outdated. -

Crumple Zones

Name: Date: Student Exploration: Crumple Zones Vocabulary: acceleration, airbag, collision avoidance system, crash test dummy, crumple zone, force, kinetic energy, Newton’s laws of motion, safety cell, seat belt, work, work-energy theorem Prior Knowledge Questions (Do these BEFORE using the Gizmo.) Two burglars run down an alley at night, trying to escape the cops. Jack is carrying a rigid metal safe. Jill is carrying an armful of antique quilts. In the pitch dark, they both collide headlong into a concrete wall. 1. Who do you think will be hurt more in the collision, and why? 2. During a car crash, what features of the car might act like either Jack’s safe or Jill’s quilts? Gizmo Warm-up When cars were first invented, the safety of passengers was not a great concern. As vehicles grew larger and faster, accidents became more deadly. Safety features went from being a rare luxury to a legal requirement. In the Crumple Zones Gizmo, you will design cars that will help a crash test dummy survive a collision. 1. To begin, do not make any changes to the DESIGN tab of the Gizmo. Select the CRASH TEST tab, and click Play ( ). After the crash, click Slo-mo replay. What happens? 2. Select the RESULTS tab to read about the results of the crash. Do you think a passenger would have survived this car crash? Explain. 2019 Get the Gizmo ready: Activity A: Click Reset ( ). Surviving a crash On the DESIGN tab, check that Sedan is selected. Introduction: Modern vehicles contain features designed to keep passengers safe in a crash. -

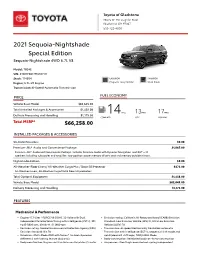

2021 Sequoia-Nightshade Special Edition Sequoia-Nightshade 4WD 5.7L V8

Toyota of Gladstone 19375 SE McLoughlin Blvd. Gladstone OR 97027 503-722-4800 2021 Sequoia-Nightshade Special Edition Sequoia-Nightshade 4WD 5.7L V8 Model: 7934E VIN: 5TDHY5B17MS187111 Stock: T14554 EXTERIOR INTERIOR Engine: 5.7L-V8 Engine Magnetic-Gray Metallic Black-Fabric Transmission: 6-Speed-Automatic Transmission FUEL ECONOMY PRICE Vehicle Base Model $63,645.00 Total Installed Packages & Accessories $1,438.00 MPG 13MPG 17MPG Delivery Processing and Handling $1,175.00 14 COMBINED CITY HIGHWAY Total MSRP* $66,258.00 INSTALLED PACKAGES & ACCESSORIES 50-State Emissions $0.00 Premium-JBL® Audio and Convenience Package $1,065.00 Premium-JBL® Audio and Convenience Package: includes Premium Audio with Dynamic Navigation and JBL® —14 speakers including subwoofer and amplifer, two-position power memory driver's seat and memory outside mirrors. Nightshade-Edition $0.00 All-Weather-Floor Liners/ All-Weather Cargo Mat / Door Sill Protector $373.00 All-Weather-Liners, All-Weather Cargo Mat & Door Sill protectors. Total Optional Equipment $1,438.00 Vehicle Base Model $63,645.00 Delivery Processing and Handling $1,175.00 FEATURES Mechanical & Performance Engine:-5.7-Liter i-FORCE V8 DOHC 32-Valve with Dual Emission-rating: California Air Resources Board (CARB) Emission Independent Variable Valve Timing with intelligence (VVT-i); 381 Standard: Low Emission Vehicle (LEV) III, Ultra Low Emission hp @ 5600 rpm; 401 lb.-ft. @ 3600 rpm Vehicle (ULEV) 70 Emission-rating: Federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Transmission:-6-speed Electronically -

Journal of KONES 2018 No. 1 Vol. 25 ISSN 1231-4005

Journal of KONES Powertrain and Transport, Vol. 25, No. 1 2018 ISSN: 1231-4005 e-ISSN: 2354-0133 DOI: 10.5604/01.3001.0012.2521 RESULTS OF THE CRASH TESTS OF ELECTRIC CARS Andrzej Żuchowski Military University of Technology, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering Institute of Motor Vehicles and Transportation Gen. W. Urbanowicza Street 2, 00-908 Warsaw, Poland tel.: +48 261837454, fax: +48 261839230 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The work presents the results of crash tests carried out with six electrical car models (from 2012-2013), with the weight of 1200-2300 kg (Smart Electric Driver, Mitsubishi IMiEV, Nissan Leaf, CODA, Ford Focus BEV, Tesla Model S). The results were published on the Internet by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (USA), and the tests involved a car travelling at the speed of 56 km/h, hitting frontally into a non-deformable (stiff) barrier, positioned perpendicularly to the car’s direction of movement. Particular attention was paid to the deformation of the car after hitting the barrier, so-called stiffness characteristics of the frontal crumple zone, and to the loads on the dummies placed at the driver’s and passenger’s seat (Hybrid III, a 50-centile man and a 5-centile woman). Results of the tests with electric cars were compared with the results of the tests with over a hundred of combustion engine cars with similar weight and type of car body (sedan, hatchback). The tests proved that, in the majority of electrical cars tested, the deformation of the frontal crumple zone after hitting an obstacle is larger than in case of similar cars with internal combustion engine.