The Metamorphosis of Suburban Mumbai: a Case Study of Mulund

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOREIGN INVESTMENT & TECHNICAL COLLOBORATION PROPOSALS APPROVED by RBI DURING the MONTH of MAY 1999 ( in Rs. Millions)

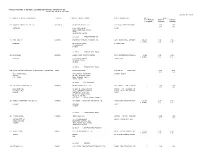

FOREIGN INVESTMENT & TECHNICAL COLLOBORATION PROPOSALS APPROVED BY RBI DURING THE MONTH OF MAY 1999 ( IN Rs. Millions) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sl NAME OF FOREIGN COLLABORATOR COUNTRY NAME OF INDIAN COMPANY ITEM OF MANUFACTURE AMT OF ROYALTY FDI APPROVED DOMESTIC EXTERNAL ( % EQUITY) (PERIOD) (PERIOD) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 231 ADVANCED ENERGY SYSTEMS LTD AUSTRALIA ASIAN ELECTRONICS LTD. ELECTRIAL INVERTER/CHARGE- - 3.00 3.00 ( 5) ( 5) AUSTRALIA D-11, ROAD NO.28, R/UPS WAGLE INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, THANE, MAHARASHTRA 400604 Location : THANE(MAHARASHTRA) 232 TAIB BANK EC BAHRAIN PENTAFOUR SOFTWARE & EXPORTS LTD DATA PROCESSING, SOFTWARE 490.00 1.50 1.50 ( 3.05) ( 5) ( 5) BAHARAIN NO.1 UNITED INDIA & CONSULTANCY CYKODAMBAKKAM CHENNAI Location : CHENNAI(TAMIL NADU) 233 BACKELMANS BELGIUM DANISH TRUST PRIVATE LIMITED DATA PROCESSING,SOFTWARE & 0.05 1.50 1.50 ( 51.00) ( 5) ( 5) BELGIUM 1/102 NORTH AVENUE CONSULTANCY SRINAGAR COLONY CHENNAI Location : CHENNAI(TAMIL NADU) 234 GULIN XINYUAN TECHNOLOGY & DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHINA VINKA INDUSTRIES SYNTYHETIO INDUSTRIAL - 1.50 1.50 ( 5) ( 5) NO.2,FUXING ROAD, B-53,GIRIRAJ INDUSTRIAL DIAMOND POWDER GUILIN, ESTATE, MAHAKALI CAVES P.R. CHINA ROAD, -

Estate 5 BHK Brochure

4 & 5 BHK LUXURY HOMES Hiranandani Estate, Thane Hiranandani Estate, Off Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) Call:(+91 22) 2586 6000 / 2545 8001 / 2545 8760 / 2545 8761 Corp. Off.: Olympia, Central Avenue, Hiranandani Business Park, Powai, Mumbai - 400 076. [email protected] • www.hiranandani.com Rodas Enclave-Leona, Royce-4 BHK & Basilius-5 BHK are mortgaged with HDFC Ltd. The No Objection Certificate (NOC)/permission of the mortgagee Bank would be provided for sale of flats/units/property, if required. Welcome to the Premium Hiranandani Living! ABUNDANTLY YOURS Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. The furniture & fixtures shown in the above flat are not part of apartment amenities. EXTRAVAGANTLY, oering style with a rich sense of prestige, quality and opulence, heightened by the cascades of natural light and spacious living. Actual image shot at Rodas Enclave, Thane. LUXURIOUSLY, navigating the chasm between classic and contemporary design to complete the elaborated living. • Marble flooring in living, dining and bedrooms • Double glazed windows • French windows in living room • Large deck in living/dining with sliding balcony doors Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. The furniture & fixtures shown in the above flat are not part of apartment amenities. CLASSICALLY, veering towards the modern and eclectic. Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. The furniture & fixtures shown in the above flat are not part of apartment amenities. EXCLUSIVELY, meant for the discerning few! Here’s an access to gold class living that has been tastefully designed and thoughtfully serviced, oering only and only a ‘royal treatment’. • Air-conditioner in living, dining and bedrooms • Belgian wood laminate flooring in common bedroom • Space for walk–in wardrobe in apartments • Back up for selected light points in each flat Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. -

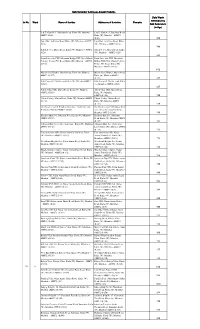

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

A Detailed Property Analysis Report of Ashford Royale in Bhandup West

PROPINSIGHT A Detailed Property Analysis Report 40,000+ 10,000+ 1,200+ Projects Builders Localities Report Created On - 7 Oct, 2015 Price Insight This section aims to show the detailed price of a project and split it into its various components including hidden ones. Various price trends are also shown in this section. Project Insight This section compares your project with similar projects in the locality on construction parameters like livability rating, safety rating, launch date, etc. What is Builder Insight PROPINSIGHT? This section delves into the details about the builder and tries to give the user a perspective about the history of the builder as well as his current endeavours. Locality Info This section aims to showcase various amenities viz. pre-schools, schools, parks, restaurants, hospitals and shopping complexes near a project. Ashford Royale Bhandup West, Mumbai 2.07 Cr onwards Livability Score 6.0/ 10 Project Size Configurations Possession Starts 4 Towers 2,3,4 Bedroom Apartment Dec `17 Pricing Comparison Comparison of detailed prices with various other similar projects Pricing Trends Price appreciation and trends for the project as well as the locality What is PRICE INSIGHT? Price versus Time to completion An understanding of how the current project’s prices are performing vis-a-vis other projects in the same locality Demand Comparison An understanding of how the strong/weak is the demand of current project and the current locality vis-a-vis others Price Trend Of Ashford Royale Ashford Royale VS Bhandup West, Mumbai -

1 / Mumbai Board

1 Estate Manager – 1 / Mumbai Board DETAILS OF RENT COLLECTION OFFICES, i. e. NAME OF COLONY, NAME OF RENT COLLECTOR, DAY OF RENT COLLECTION, TIME OF RENT COLLECTION . Sr. NAME OF COLONY NAME OF RENT DAY OF RENT TIME OF RENT No. COLLECTOR COLLECTION COLLECTION 1 2 3 4 5 1 Neharu Nagar, Shri. A.A.Shinde Monday to 9.00 A.M. to Kurla (East) Wedensday 12.00 A. M. 2 Tilak Nagar, Shri. A.A.Shinde Thirsday to 9.00 A.M. to New Tilak Nagar Saturday 12.00 A. M. ( 2nd & 4th Saturday Closed ) 3 Vinoba Bhave Nagar, Shri. R.A.Gagat Monday to 9.00 A.M. to Netaji Nagar, Kurla Saturday 12.00 A. M. (West) 4 Pant Nagar, Shri. S.V.Walekar Monday to 9.00 A.M. to Chittaranjan Nagar, Saturday 12.00 A. M. Ghatkoper (East) 2 Estate Manager – 2 / Mumbai Board DETAILS OF RENT COLLECTION OFFICES, i. e. NAME OF COLONY, NAME OF RENT COLLECTOR, DAY OF RENT COLLECTION, TIME OF RENT COLLECTION. Sr. NAME OF COLONY NAME OF RENT DAY OF RENT TIME OF RENT No. COLLECTOR COLLECTION COLLECTION 1 Samata Nagar Shri. Manoj Shirale Monday 9.00 A. M. to Kandiwali 11.00 A.M 2 Oshiwara, Vaibhav Palace & Shri. Manoj Shirale Tuesday to 9.00 A. M. to Patliputra Thirsday 11.00 A.M 3 Magathane, Borivali Shri. Manoj Shirale Friday 9.00 A. M. to 11.00 A.M 4 Tenemaents Checking Shri. Manoj Shirale Saturday 9.00 A. M. to 11.00 A.M 5 Nirmal Nagar, Vijay Nager, Shri. -

Bulk Generator Addresses.Xlsx

Bulk Generator Addresses-Eastern Suburbs Daily Waste Generation by Sr No. Ward Name of Socities Addresses of Societies Remarks Bulk Generators (in Kgs) L & T, Gate No.5, Sakivihar Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai – L & T, Gate No.5, Sakivihar Road, 400072 (0.46) Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 (0.46) 460 Light Hall, Sakivihar Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 Light Hall, Sakivihar Road, Kulra (0.74) (W), Mumbai – 400072 (0.74) 740 Ashok Tower, Marva Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 Ashok Tower, Marva Road, Kulra (0.29) (W), Mumbai – 400072 (0.29) 290 Satair Lake side CHS, Mountain Bridge CHS (New Mhada Satair Lake side CHS, Mountain Colony), Powai, JVL Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 Bridge CHS (New Mhada Colony), (0.632) Powai, JVL Road, Kulra (W), Mumbai – 400072 (0.632) 632 Manav Sthal Heights, Marva Road, Kurla (w), Mumbai- Manav Sthal Heights, Marva Road, 400072 (0.267) Kurla (w), Mumbai-400072 (0.267) 267 N.G. Complex, Marva road, Kurla (w), Mumbai-400072 N.G. Complex, Marva road, Kurla (0.225) (w), Mumbai-400072 (0.225) 225 Ashok Vihar CHS, Marva Road, Kurla (W), Mumbai – Ashok Vihar CHS, Marva Road, 400072.(0.160) Kurla (W), Mumbai – 400072.(0.160) 160 Udyan Society, Marwa Road, Kurla (W), Mumbai-400072 Udyan Society, Marwa Road, (0.139) Kurla (W), Mumbai-400072 (0.139) 139 Om Shanti complex Bhudhaji wadi lane, Sakivihar road, Om Shanti complex Bhudhaji wadi Kurla (w), Mumbai-400072 (0.196) lane, Sakivihar road, Kurla (w), Mumbai-400072 (0.196) 196 Harshvardhan Soc, Sakivihar Road, Kurla (W), Mumbai- Harshvardhan Soc, Sakivihar 400072 (0.127) Road, Kurla (W), Mumbai-400072 (0.127) 127 Adityavardhan Soc, (Aristocrat Lane), Kurla (W), Mumbai- Adityavardhan Soc, (Aristocrat 400072 (0.138) Lane), Kurla (W), Mumbai-400072 (0.138) 138 Tata Symphany CHS, Nahar Amrut Shakti Road, Kurla Tata Symphany CHS, Nahar (W), Mumbai – 400072. -

IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS Helpline TEL 1 TEL 2 TEL 3 FAX M.C.G.M Control Rooms 1916

IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS Helpline TEL 1 TEL 2 TEL 3 FAX M.C.G.M Control Rooms 1916 Disaster Management Control rooms 22704403 22694725 22694727 22694719 Central Complaint Registration System 1916 Disaster Helpline 108 Nodal officer of MCGM during any disaster Chief Fire Officer 23074923 23076111 Chief Medical Superintendent 26406787 26420131 Chief Officer, DMP & CCRS 22694727 22694725 National Disaster Management Authority Disaster Management , New Delhi 011-26701700 National Institute of Disaster 23702432 23705583 23766146 Management Solid Waste Management Control Room Worli (City) 24935687-88 24935689-93 24922138 24922166 25113510, Ghatkopar (ES) Pantnagar 25113509 25113513 26176886, Santacruz (WS) 26182251-6 26182256 26123266 Water Supply Control Malbar Hill (city) 23678109 23695835 23612577 Bhandarwada Reservoir 23770446 23756008 Vile Parle (Western Sub) 26146852 26184173 Ghatkopar (Eastern Sub) 25153258 25153740 M.S.E.B. Control M.S.E.B. (Bandra) 26472131 26474211 M.S.E.B. (Bhandup) 25664323 25663408 M.S.E.B. (Mulund West) 25686666 25653408 25931001 M.S.E.B. (Mulund East) 21636945 B.E.S.T. Control Electric House 22856262 22799591 Colaba Depot 22856262 Transport Wadala 24146533 24184489 24137937 Electric Supply 24146262 24124242 24124993 Colaba Fuse 22182709 22184242 22162648 Pathakwadi System Control 22067893 22082875 22085888 Pathakwadi Fuse Control 22084242 22084243 22086351 Pathakwadi Fault Control 22066611 22066661 22087234 Grant Road Fuse 23094242 23099686 Dadar Fuse 24124993 24124242 24123162 Mahim Fuse 24444242 24461634 Fire Brigade Control Room 101 Fire Station 23076111 23086181 23086182 23076112 B.A.R.C. Fire Station 25505222 25592222 R.C.F. Fire Station 25522222 25507624 Thane Fire Station 25331600 25334216 Mumbai Port Trust Fire Officer 23778704 66566260 Airport Fire Station 26829197 31003438 Mantralaya Emergency Operation 22854168 22023266 22027990 Centre Mantralaya. -

Mulund, Mumbai

® Mulund, Mumbai The established residential destination of Mumbai Micro Market Overview Report April 2018 About Micro Market Major Growth Drivers Tagged as the 'Prince of Suburbs’, Mulund is one of the well-planned Ÿ Presence of well-established Ÿ Eastern Express Highway residential destinations of Mumbai. Mulund’s proximity to Navi Mumbai physical and social infrastructure provides easy access to and Thane also adds to the location advantage. Surrounded by Sanjay various parts of Mumbai Gandhi National Park on one of the sides, Mulund also enjoys a calm and serene environment. Designed by architects Crown & Carter, the development of Mulund dates back to the time of Mauryan empire during the early 1900s. Decades ago, Mulund was a part of the Thane city and as the city expanded, Mulund came under the purview of Mumbai Municipal Corporation. Thereafter, the micro market witnessed a drastic Ÿ Proximity to employment hubs Ÿ Construction of proposed transformation from the centre of trade and industries to one of the such as Vikhroli, Powai, BKC metro rail is likely to enhance upscale residential neighbourhoods of Mumbai with towering skylines and Andheri connectivity and swanky shopping malls. In addition to the presence of good social infrastructure such as hospitals, malls, educational institutes and entertainment zones, Mulund also boasts of vast greenery, verdant landscapes and salubrious atmosphere. Rapidly improving physical infrastructure also contributes to the development of commercial office spaces in Mulund, however, the city continues to be a predominantly residential Ÿ Construction of proposed Goregaon- Ÿ One of the greenest stretches destination. Mulund Link Road is expected to of Mumbai improve connectivity to the Western suburbs Fortis Hospital Connectivity Mulund is well-connected not just to the island city and other suburbs, but also with other regions of Mumbai Metropolitan Region, through a grid of roads and an established rail network. -

Ariisto Codename Big Boom A4

MUMBAI'S HAPPIEST REAL ESTATE BOOM LIMITED PERIOD PRE-LAUNCH: 19 AUG - 3 SEP LOCATION 22ND CENTURY BOOMTIME A BOOMING PRE-LAUNCH PRIMED FOR A BOOM LIFESTYLE BOOM FOR REAL ESTATE OPPORTUNITY CODENAME BIG BOOM - MUMBAI’S HAPPIEST PRE-LAUNCH BEGINS! THE LUXURY OF SOBO • THE PRIVILEGED LIFESTYLE OF POWAI • NOW AT THANE PRICES Ariisto presents the first and biggest RERA-registered pre-launch opportunity to acquire 22nd century 2 and 3 bed techno-luxury homes in the most awaited neighbourhood of Mumbai’s happiest and most liveable suburb - Mulund. A block-buster offering to move into the rarest location of Mumbai at never-seen-before prices starting `1.35 Cr^, limited to an extremely short-lived pre-launch opportunity from 19th August - 3rd September. OFFER HIGHLIGHTS Mumbai is India’s most expensive and thriving real estate market with prices for a quality Grade-A • Mumbai's first RERA-registered mega pre-launch. 2 BHK ranging from `2 Cr (Suburbs) to `10 Cr+ (South Mumbai) and 3 BHK ranging from `2.5 Cr • Mumbai's finest neighbourhood in the serene to `15 Cr+. The demand for sub-1.5 Cr luxury homes setting of Yogi Hills, Mulund. has forced movement to Thane and Navi Mumbai. • Mumbai's first-ever 22nd century homes at Codename Big Boom presents a once-in-a-lifetime Thane prices. opportunity to own luxury residences at the most desired location of Mumbai at Thane prices. • 2 and 3 bed techno-luxury residences starting at just `1.35 Cr^. Naturally-blessed locations in Mumbai are rare and command up to 55% higher premium as seen in • Book a home by paying just 10% now and the Malabar Hill in South Mumbai, Five Gardens in Central rest spread conveniently until possession. -

Redharavi1.Pdf

Acknowledgements This document has emerged from a partnership of disparate groups of concerned individuals and organizations who have been engaged with the issue of exploring sustainable housing solutions in the city of Mumbai. The Kamala Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture (KRVIA), which has compiled this document, contributed its professional expertise to a collaborative endeavour with Society for Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC), an NGO involved with urban poverty. The discussion is an attempt to create a new language of sustainable urbanism and architecture for this metropolis. Thanks to the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP) authorities for sharing all the drawings and information related to Dharavi. This project has been actively guided and supported by members of the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF) and Dharavi Bachao Andolan: especially Jockin, John, Anand, Savita, Anjali, Raju Korde and residents’ associations who helped with on-site documentation and data collection, and also participated in the design process by giving regular inputs. The project has evolved in stages during which different teams of researchers have contributed. Researchers and professionals of KRVIA’s Design Cell who worked on the Dharavi Redevelopment Project were Deepti Talpade, Ninad Pandit and Namrata Kapoor, in the first phase; Aditya Sawant and Namrata Rao in the second phase; and Sujay Kumarji, Kairavi Dua and Bindi Vasavada in the third phase. Thanks to all of them. We express our gratitude to Sweden’s Royal University College of Fine Arts, Stockholm, (DHARAVI: Documenting Informalities ) and Kalpana Sharma (Rediscovering Dharavi ) as also Sundar Burra and Shirish Patel for permitting the use of their writings. -

Urban Biodiversity

NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY & ACTION PLAN – INDIA FOR MINISTRY OF ENVIRONEMENT & FORESTS, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA BY KALPAVRIKSH URBAN BIODIVERSITY By Prof. Ulhas Rane ‘Brindavan’, 227, Raj Mahal Vilas – II, First Main Road, Bangalore- 560094 Phone: 080 3417366, Telefax: 080 3417283 E-mail: < [email protected] >, < [email protected] > JANUARY 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Nos. I. INTRODUCTION 4 II. URBANISATION: 8 1. Urban evolution 2. Urban biodiversity 3. Exploding cities of the world 4. Indian scenario 5. Development / environment conflict 6. Status of a few large Urban Centres in India III. BIODIVERSITY – AN INDICATOR OF A HEALTHY URBAN ENVIRONMENT: 17 IV. URBAN PLANNING – A BRIEF LOOK: 21 1. Policy planning 2. Planning authorities 3. Statutory authorities 4. Role of planners 5. Role of voluntary and non-governmental organisations V. STRATEGIC PLANNING OF A ‘NEW’ CITY EVOLVING AROUND URBAN BIODIVERSITY: 24 1. Introduction 2. General planning norms 3. National / regional / local level strategy 4. Basic principles for policy planning 5. Basic norms for implementation 6. Guidelines from the urban biodiversity angle 7. Conclusion VI. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 35 2 VII. ANNEXURES: 36 Annexure – 1: The 25 largest cities in the year 2000 37 Annexure – 2: A megalopolis – Mumbai (Case study – I) 38 Annexure – 3: Growing metropolis – Bangalore (Case study – II) 49 Annexure – 4: Other metro cities of India (General case study – III) 63 Annexure – 5: List of Voluntary & Non governmental Organisations in Mumbai & Bangalore 68 VIII. REFERENCES 69 3 I. INTRODUCTION About 50% of the world’s population now resides in cities. However, this proportion is projected to rise to 61% in the next 30 years (UN 1997a). -

Malaria in Bombay, 1928

Malaria in Bombay, 1928 BY M.uon G. COVELL, M;D. (Lond.), D.T.M. & .H. (Eng.), F.E.S., I.M.B., .Assistant Dirsctor, Malaria Bumy of India (on special duty with the Government of Bombay) :bOMBAY PBINTED AT THE GOVEBNMENT CENTBAL PRESS . 1928 PR.E-F ACE I THE inquiry into malarial. conditions in Bombay which forms' the subject of this report was carried out during the period March 20th to September 21st, 1928. In presenting the report I wish to. convey my grateful thanks to the following gentlemen for their assistance during the investigation :- The President and Members of the Malaria Advisory Committee. Dr. J. E. Sandilands, Executive Health Officer, Bombay. Dr. J. S. Nerurkar, Assistan~ to the Executive Health Officer (Malaria), and the staff of the Malaria Department, whose services were placed at my disposal whenever they were required ; and . especially to Captain G. G. Limaye, whose assistance in recording the data of the Spleen Census of School Children w:as most valuable. The 1\funicipal School Medical Inspectors, who arranged the programme for the Spleen Census. Lieut.-Col. F .. ;I?. Mackie, I.M.S., Director, and MajorS. S. Sokhey, Acting Director, of the Haffkine Institute, for th& facilities placed at my disposal there. Captain B. S. Chalam,.. Medical Officer of the Development Department. Dr. P. A. Dalal, Medical Officer of the E. D. Sassoon group of mills. Mr. J. D. Pember, Superintending Engineer, and Mr. W. F. Webb, Deputy Superintending Engineer of the E. D. Sassoon group of mills. Mr. A. Hale White, Executive Engineer, General Works, Bombay ·Port Trust.