Residents' Satisfaction with Residential Quality of Life In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization and Delineation of Aquifer in Part of Omoku, Rivers State, Nigeria

IOSR Journal of Applied Geology and Geophysics (IOSR-JAGG) e-ISSN: 2321–0990, p-ISSN: 2321–0982.Volume 2, Issue 4 (Jul-Aug. 2014), PP 30-37 www.iosrjournals.org Characterization and Delineation of Aquifer in Part of Omoku, Rivers State, Nigeria 1I. Tamunobereton-ari, 2V. B. Omubo-Pepple and 3A.R.C. Amakiri 1,2,3Department of Physics, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port Harcourt 500001, Nigeria. Abstract: Hydrogeological work was carried out to providing an alternative source of portable water supply to Omoku and its environs as their major source of water which is surface water had been contaminated/polluted by oil and gas exploration, exploitation and other anthropogenic activities in the area. To obtaining reliable data and achieving the aim, geoelectric sounding method and Schlumberger array was employed with the use of a digital averaging instrument ABEM terrameter SAS 300 model that displays the resistance measurements directly with a maximum current electrode separation (AB) of 100m. WinResist software computer iterative procedure was used, which aided to obtaining interpreted depths and resistivities from field data. The results of the geoelectric survey were tied to various lithologies by calibrating the geoelectric values with borehole data which enabled us to establish the aquiferous zones. The aquifers were located at depth of about 22m to 30m based soil profile and high resistivity values ranging from 3415m to 4555m. The information from the findings can be successfully used to harnessing and supply safe, portable and sustainable water to the people of Omoku and its environs in Rivers State, Nigeria. Keywords: Groundwater, aquifer, geoelectric layer, Vertical Electrical Sounding (VES) I. -

Downloaded for Personal Non-Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE POLITICS AMO ADMINISTRATION OF COhTUNITY DEVELOPMENT IN THE RIVERS STATE OF NIGERIA BY LAURENCE A.8. lYAGOA Submitbed for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow Duly 1976 ProQuest Number: 10647271 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uesL ProQuest 10647271 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. ProQuest LLO. -

Ikwerre Intergroup Relations and Its Impact on Their Culture

83 AFRREV VOL. 11 (2), S/NO 46, APRIL, 2017 AN INTERNATIONAL MULTI-DISCIPLINARY JOURNAL, ETHIOPIA AFRREV VOL. 11 (2), SERIAL NO. 46, APRIL, 2017: 83-98 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v11i2.7 Ikwerre Intergroup Relations and its Impact on Their Culture Chinda, C. Izeoma Department of Foundation Studies Port Harcourt Polytechnic, Rumuola Phone No: +234 703 667 4797 E-mail: [email protected] --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract This paper examined the intergroup relations between the Ikwerre of the Niger Delta, South-South geopolitical zone of Nigeria and its impact on their culture. It analyzed the Ikwerre relations with her Kalabari and Okrika coastal neighbours, as well as the Etche, Eleme, Ekpeye, Ogba Abua and the Igbo of Imo state hinterland neighbours. The paper concluded that the internal developments which were stimulated by their contacts impacted significantly on their culture. Key words: Ikwerre, Intergroup Relations, Developments, Culture, Neighbour. Introduction Geographical factors aided the movement of people from one ecological zone to another in migration or interdependent relationships of trade exchange. These exchanges and contacts occurred even in pre-colonial times. The historical roots of inter-group relations of the Ikwerre with her neighbours, dates back to pre-colonial times but became prevalent from the 1850 onward when the Atlantic trade became emphatic on agrarian products as raw materials to the industrial western world. This galvanized the hitherto existing inter-group contact between the Ikwerre and her neighbouring potentates. Copyright © International Association of African Researchers and Reviewers, 2006-2017: www.afrrevjo.net. -

The Challenges of Developing Buguma Town As a Secondary City in Rivers State Nigeria

KIU Journal of Social Sciences KIU Journal of Social Sciences Copyright©2019 Kampala International University ISSN: 2413-9580; 5(2): 19–30 The Challenges of Developing Buguma Town as a Secondary City in Rivers State Nigeria VICTOR OWITUBO CHARLES, NALUBA GOODY NWIEKPIGI Ignatius Ajuru University of Education, Rumuolumeni, Port Harcourt Abstract. This study investigated the challenges Keywords: Challenges, Secondary, City, of developing Buguma as a secondary city in Developing. Rivers State. This study made use of public opinion survey research design with a sample 1. Introduction size of 200 respondents. Data was sourced from the research instrument known as developing 1.1 Background and Overview Buguma Secondary City Questionnaire (DBSCQ) designed along the Likert-type 4-point The philosophy underlying regional planning scale rating. Data was analyzed with both programmes is that the problems of urban and descriptive and inferential statistics. Simple rural areas are intricately connected and should percentage was used to analyze the descriptive be so solved within a regional framework and inferential statistics. Simple percentage was (Slatter 2012, World Bank, 2011). Similarly, used to analyze the socio-demographic global economic activities and population background of the respondents while mean and dynamics are increasingly concentrated in big standard deviation were used to analyze the cities and as a result, urban research has tended research questions. One way analysis of variance to focus on large metropolitan areas at the (ANOVA) was used to analyze the hypotheses. expense of secondary cities which have been a The results of the study revealed that majority of rediscovery of the city in academic discourse the respondents were male 108 (54%); were (Marais, Rooyen, Lenka and Cloete. -

AFRREV VOL 13 (4), S/NO 56, SEPTEMBER, 2019 African Research Review: an International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia AFRREV Vol

AFRREV VOL 13 (4), S/NO 56, SEPTEMBER, 2019 African Research Review: An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia AFRREV Vol. 13 (4), Serial No 56, September, 2019: 74-85 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v13i4.7 Chieftaincy Institution and Military Formations in the Eastern Niger Delta of Nigeria Adagogo-Brown, Edna, PhD. Associate Professor of History Captain Elechi Amadi Polytechnic E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +2348033091227 Abstract This paper showed the military formations in the Eastern Niger Delta prior to Nigerian independence which the British colonial government tried to destroy in the wake of the establishment of the Protectorate of the Oil Rivers and Consular paper treaties. The Chieftaincy institution in the Eastern Niger Delta dates to at least 1000 years ago. After the migration story had been completed, the various communities that made up the Eastern Niger Delta commenced the early political and economic institutions with the ward or wari system of government and the long-distance trade with their neighbours. In the early fifteenth century, the Asimini ward in Bonny and Korome ward in Kalabari produced their early kings. The Chieftaincy institution assumed a greater relevance in the kingdoms of Bonny and Kalabari with the emergence of King Perekule of Bonny and King Amachree of Kalabari respectively. These two kings introduced the war canoe house political system in response to the slave trade which had increased tremendously with the entrance of Britain. The risks and the competitions among the City-states of Bonny, Kalabari, Okrika and Nembe-Brass to procure slaves necessitated the acquisition of war canoes to equip and constitute the military arm of the states. -

The Place of Bonny in Niger Delta History (Pp. 36-45)

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 5 (5), Serial No. 22, October, 2011 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v5i5.4 The Place of Bonny in Niger Delta History (Pp. 36-45) Orji, Kingdom E. - Department of History & Diplomatic Studies, Rivers State University of Education, Rumuolumeni, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Tel: +2348056669109 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Bonny occupies a strategic position in the Niger Delta Studies. Issues to be examined in this article include the circumstances surrounding the founding of this unique settlement on the Rio Real of Eastern Delta and its implications for the reconstruction of the history of other Niger Delta communities. An attempt will be made to unravel the strains encountered by the indigenous economy of our study area in the face of the assault of Old and New imperialism of the West from the fifteenth centuries to the recent past. Bonny’s strategic and pivotal role in the spread of Christianity in the study area is also highlighted. Early history The indigenous settlers of Bonny are known as the Ibani with a distinct language that goes by the same name. In fact the Ibani language has been classified under languages spoken in Eastern Ijo which themselves belong to the Ijoid group (Efere and Willamson 1989, pp. 43-44, Derefaka 2003, p. 23). Dike (1956, p.24) has given the impression that the Bonny are of Igbo origin. He suggest that the first migrants to this area, under their veritable leader Alagberiye himself, a distinguished hunter, had made incursions into this area between 1450–1800. -

Roadblocks to Equal Distribution of Inheritance in Okrika Clan Rivers State, Nigeria: Implication for Family Counseling

International Journal of Innovative Legal & Political Studies 4(4):30-36, Oct.-Dec. 2016 © SEAHI PUBLICATIONS, 2016 www.seahipaj.org ISSN: 2354-2926 Gender Bias: Roadblocks To Equal Distribution Of Inheritance In Okrika Clan Rivers State, Nigeria: Implication For Family Counseling 1KENNEDY Margaret G, M.Ed & 2Maxwell D. EREMIE, Ed.D Department of Educational Foundations, Faculty Of Science And Technical Education Rivers State University Of Science And Technology Nkpolu-Oroworukwo, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Emails: [email protected]; : [email protected] ABSTRACT Gender based issues have become household concern in countries all over the world. A discourse on gender bias will always be greeted with excitement, insight or even disappointment by many. The issue of gender bias in the distribution of inheritance has torn families apart, women were crippled emotionally, their self concept thwarted and potentials not fully maximized in line with this in view, this paper takes a look at the general perception of people on gender bias issues. The views of custom and the law about gender discrimination, what the law has done about female inheritance, lessons from the judgments, implication for family counseling, conclusion/recommendations were made based on the position taken. Keywords, gender bias, distribution of inheritance, discrimination, inequality. INTRODUCTION Okrika clan is one of the ancient city states of the Niger Delta, it existed as an entity with its rich culture and tradition before the advent of Christianity and colonialism. The clan is made up of three (3) Local Government Areas in Rivers State namely: Okirika Local Government Area (WALGA) Ogu/Bolo Local Government Area and Part of Port Harcourt City Local Government Area by the Hargrove agreement of 18th May 1913 between leading chiefs and headmen of the various communities which owned Port Harcourt on the one hand, and Alexander George Boyle and Saint George, Deputy Governor of the colony and protectorate of southern Nigeria on the other hand. -

Does the Greater Port Harcourt Master Plan 2008 Meet Aspirations for Liveable City?

Ede et al., Greater Port Harcourt Master Plan 2008, 47th ISOCARP Congress 2011 Does the Greater Port Harcourt Master Plan 2008 meet Aspirations for Liveable City? By Precious N. Ede, Opuenebo B. Owei and Chimbiko Iche Akarolo In 2007 the government of Rivers State, Nigeria contracted a South African firm to produce a master plan for a new city called Greater Port Harcourt to be situated in the outskirts of the old city. The Greater Port Harcourt Master Plan 2008 is here examined in the context of current thinking as to whether it has credentials that meet aspirations for modern liveable cities. The new city plan assumes that Port Harcourt will continue to grow at its current rate so there is need to respond pro-actively to the reality of meeting cogent challenges. The infrastructure to be provided must be sustainable, that is, there should be continuity of effective service delivery by operators, by way of renewal, upgrading and expansion to cope with the city growth. Provision of services will be private sector driven, while government is politically ready to amend laws, regulations and policies to create an enabling environment for private sector to thrive in driving the development initiatives. The plan provides a long-term vision for the city based on sustainability: social, economic and political equity. Sustainability is hinged on continual improvement based on accountability, transparency and good governance. The master plan aims at a development that positively encourages the creation of a mixed community of 350,000 housing units, initially. The energy infrastructure utilizes the natural resources in the region such as natural gas for powering turbines and providing domestic fuel, with a little solar power. -

Multinational Corporations As Partners in Curbing Insecurity in Rivers State: the Community Policing Approach

International Journal of Innovative Development and Policy Studies 7(4):39-44, Oct--Dec., 2019 © SEAHI PUBLICATIONS, 2019 www.seahipaj.org ISSN: 2467- 8465 Multinational Corporations As Partners In Curbing Insecurity In Rivers State: The Community Policing Approach *Daerego Ilomabo Taylor; Prof. I. S. Nzeneri & Dr. G. Adekola Department of Adult Education and Non-formal Education University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria *Corresponding Author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Insecurity has become a major global issue in the last few decades and Nigeria has had a fair share of this menace. There has been growing concerns over the spate of violence, kidnapping, cultism, militancy, killings and other associated crimes in Rivers State and other states in the nation. Some communities have been deserted and companies operating there have left or relocated leaving a huge economic impact on the states and nation at large. In a bid to deal with this issue, successive governments have adopted the traditional policing model in crime fighting but this seems not to have yielded the desired results. The spate of crimes in most communities in Rivers State seems not to have reduced in spite of the efforts of the police and other security forces. There is a need therefore for a change of approach to a more inclusive and integrated efforts from communities, multinationals operating in the communities and the police in curbing crimes and ensuring safer neighbourhoods in the state. This is what the community police model advocates. This study therefore examined the community policing approach and how it takes cognizance of the efforts of both community members and multinational corporations specifically. -

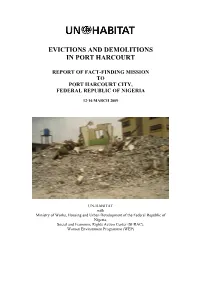

Port Harcourt Fact Finding Mission

EVICTIONS AND DEMOLITIONS IN PORT HARCOURT REPORT OF FACT-FINDING MISSION TO PORT HARCOURT CITY, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA 12-16 MARCH 2009 UN-HABITAT with Ministry of Works, Housing and Urban Development of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Social and Economic Rights Action Center (SERAC), Women Environment Programme (WEP) The responsibility for the content of this report, including its recommendations, rests entirely with UN-HABITAT. The time devoted to the Mission and the contributions of those individuals and organisations listed in the annexes are acknowledged and appreciated. This report has been produced without formal editing by the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the United Nations, and a failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. Excerpts from the text may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. Cover photo: Legal structure along the upper part of Abonnema Wharf, demolished during the period 10 to 13 February 2009. Photo credit: Social and Economic Rights Action Center (SERAC) UN-HABITAT Abuja and Nairobi, August 2009 ii -

Alafaka Tobin M.B, B.S

A COMPARISON OF UPTAKE OF INTERMITTENT PREVENTIVE TREATMENT OF MALARIA IN PREGNANCY IN URBAN AND RURAL PUBLIC PRIMARY HEALTH CARE CENTRES IN RIVERS STATE BY ALAFAKA TOBIN M.B, B.S A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE NATIONAL POSTGRADUATE MEDICAL COLLEGE OF NIGERIA IN PART FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF FELLOWSHIP OF THE MEDICAL COLLEGE IN PUBLIC HEALTH MAY, 2016 1 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this study, or part of it, has not been and will not be submitted for any other diploma, fellowship or any other examination. ……………..………. ALAFAKA TOBIN M.B, B.S 2 CERTIFICATION This is to certify that this dissertation titled “A Comparison Of Uptake Of Intermittent Preventive Treatment Of Malaria In Pregnancy In Urban And Rural Public Primary Health Care Centres In Rivers State” was carried out by Alafaka Tobin, a Senior Registrar in the Department of Community Medicine, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital under our supervision. ………………………….. ………………..…… Dr. C. I. Tobin-West Dr. C. A. Onoka MD, MPH, FMCPH MBBS, DLSHTM, MPH, MSc, FWACP Senior Lecturer, Consultant Community Medicine Lecturer, Consultant Community Medicine Department of Community Medicine University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital Nsukka, Enugu Port Harcourt, Rivers State …………………… Dr. K. E. Douglas Head of Department Community Medicine University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital Port Harcourt Rivers State 3 DEDICATION This book is dedicated to my husband Mr. Derefaka Tobin whose words of encouragement motivated me to commence and complete this dissertation. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am very grateful to my supervisors, Dr. C.I. Tobin-West and Dr. -

Belief in the Supreme Being in Ogoloma in Okrika Local Government, Rivers State

Ibanichuka E. A. L. et al 1 BELIEF IN THE SUPREME BEING IN OGOLOMA IN OKRIKA LOCAL GOVERNMENT, RIVERS STATE APPAH S.T.K. Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies Niger Delta University Wilberforce Island Amassoma Bayelsa State. Abstract This articles traces the existence and worship of a supreme being in Okrika LGA in Rivers state. It argues that Tamuno which is the Supreme Being in Okrika LGA traditional religion is overwhelmingly evident in the indigenous names borne by the indigenes of the locality. The article therefore challenges the veracity of earlier researchers who claim that Okrika people did not worship a supreme god. Introduction Ogoloma is one of the nine main towns that made up the Okrika City-State alongside Kirike (Okrika), Ibaka, Ogbogbo,Ogu, Bolo, Abuloma, Isaka and Ele. Okrika (Wakirike) which is the name used in referring to the area, is located at the Eastern area of the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, Ogoloma is one of the major towns of Okrika Local Government Area of Rivers State. Ogoloma is as old as other prominent pre-colonial towns and areas like Bonny, Brass, Nembe, Opobo, etc. The major commercial activities in the area are fishing and trading. The trade pattern was earlier based on trade by barter before the introduction of cowries and monetary trading. The sea was the only means of livelihood of Ogoloma town, while majority of the men go to the sea with local canoe boats alongside their fishing nets and hooks, the other party which are the women in majority also go to the sea with their town tools to hunt sea foods like periwinkle (Isamu) and Ingbe.